People speak about their discovery of Real Deal Magazine in revelatory terms. This is mostly because it contains scenes of black characters perpetrating such extreme violence and political incorrectness that it is capable of searing a new wrinkle into your brain. Only six issues were published from 1989 to 2001, but they were enough to leave an impression in the minds of a certain cross section of artists and readers who prefer unrepentant brutality to superheroes and schlock.Underneath Real Deal’s over-the-top tales of “urban terror” lies a painfully raw nerve. In a way, the comic’s seemingly exaggerated violence was a peek inside the illogical lobster-tank psyche of ghetto life and its resulting insanity. A world in which its inhabitants can’t help but pull one another down, which, come to think of it, is a lot like this awful place we call reality.Real Deal’s creators, illustrator Lawrence Hubbard and writer Herald Porter McElwee (H.P.), were drawn together through a shared frustration with their lives as black men in early-80s LA, where Rodney King-style beatings were as common as the sunset. Fittingly, they met in 1979 while working a minimum-wage stocking and unloading job in the bowels of California Federal Bank. They soon commiserated over their grievances: the pigs, their grim career opportunities, and, most of all, that they grew up a couple of bastards after their fathers walked out on their families.“That was our bond,” Lawrence said. “We’d sit around and talk about how we wished we’d had a dad in the house. We shared that feeling—that rage and anger. It’s like going through a war. Unless you’ve experienced it, you don’t know what it feels like.” In 1985, they were still slaving away at California Federal and, through their friendship, found an unexpected channel for their anger. Like many good ideas, Real Deal began as a doodle on some scrap paper during a break from their shitty job. Herald Porter McElwee, the late Real Deal writer, stands above Lawrence Hubbard, the magazine’s co-creator and illustrator, while fittingly brandishing a handgun.“One day I come down to the basement for lunch and H.P. is drawing stick figures,” Lawrence said. “He had this crazy story with this guy selling oranges on the median and this other guy named G.C. driving down the street. G.C. takes the car and runs right over the guy on the median. Then G.C.’s old lady says, ‘G.C., you sure fucked him up.’ And he turns to her and says, ‘That could be you too, bitch, if you fuck up.’”Lawrence burst into bellowing laughter when he described it to me, as I’m sure he did the first time he read H.P.’s story. From then on he took H.P.’s crude sketches and turned them into full-blown comics, defining Real Deal’s signature look with his bold black ink and perspective angles that are reminiscent of Raymond Pettibon and Gary Panter, even though at the time Lawrence was unaware of their work. He began drawing at three years old, a by-product of finding cheap ways to keep himself busy as the poorest kid in his middle-class neighborhood of Mid-City. When Lawrence was ten, his father abandoned his family. His single mother was unable to afford supplies, so he made do with broken pencils and scraps of paper, sometimes attempting to redraw the militant cartoons he saw in Black Panther literature from the early 70s.By the time Lawrence was working at California Federal, he’d all but given up on art. It wasn’t until he saw H.P.’s merciless stick figures that Lawrence’s compulsion to draw returned, practically overnight and in full force.

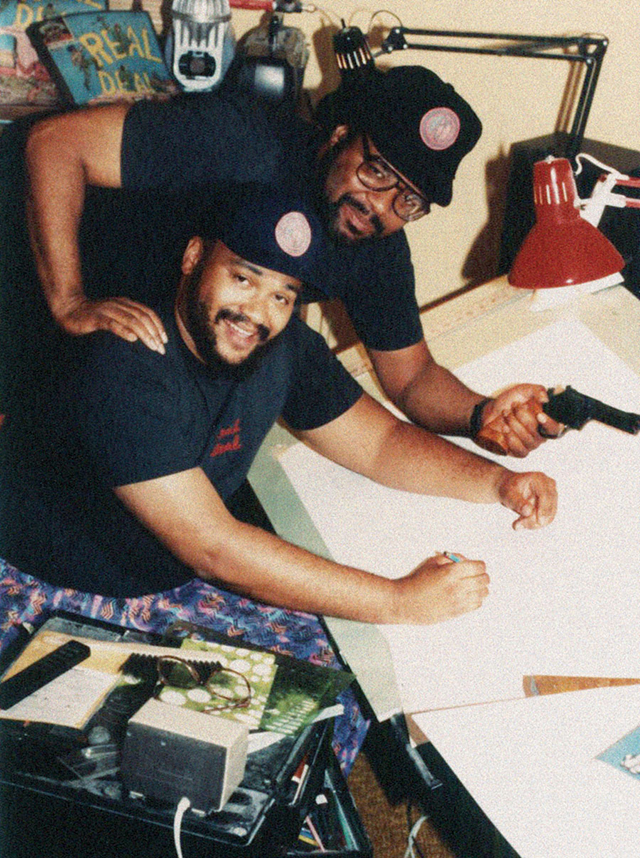

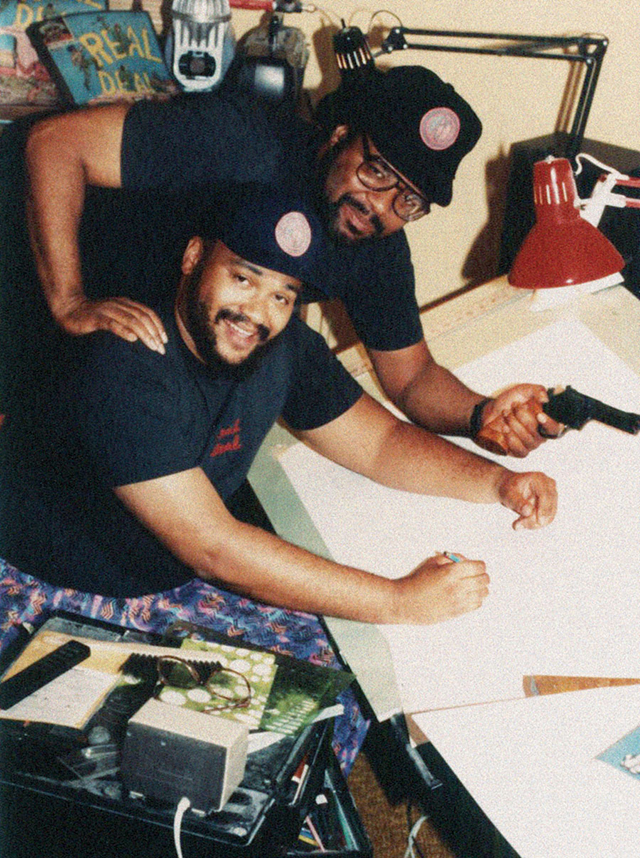

Herald Porter McElwee, the late Real Deal writer, stands above Lawrence Hubbard, the magazine’s co-creator and illustrator, while fittingly brandishing a handgun.“One day I come down to the basement for lunch and H.P. is drawing stick figures,” Lawrence said. “He had this crazy story with this guy selling oranges on the median and this other guy named G.C. driving down the street. G.C. takes the car and runs right over the guy on the median. Then G.C.’s old lady says, ‘G.C., you sure fucked him up.’ And he turns to her and says, ‘That could be you too, bitch, if you fuck up.’”Lawrence burst into bellowing laughter when he described it to me, as I’m sure he did the first time he read H.P.’s story. From then on he took H.P.’s crude sketches and turned them into full-blown comics, defining Real Deal’s signature look with his bold black ink and perspective angles that are reminiscent of Raymond Pettibon and Gary Panter, even though at the time Lawrence was unaware of their work. He began drawing at three years old, a by-product of finding cheap ways to keep himself busy as the poorest kid in his middle-class neighborhood of Mid-City. When Lawrence was ten, his father abandoned his family. His single mother was unable to afford supplies, so he made do with broken pencils and scraps of paper, sometimes attempting to redraw the militant cartoons he saw in Black Panther literature from the early 70s.By the time Lawrence was working at California Federal, he’d all but given up on art. It wasn’t until he saw H.P.’s merciless stick figures that Lawrence’s compulsion to draw returned, practically overnight and in full force.

For his part, H.P. was fueled by an equally intense compulsion to write up these intensely absurd and homicidal doodle-stories starring G.C., becoming even more prolific once he realized Lawrence could turn them into technically impressive comics. It’s always tempting to psychoanalyze artists, but in H.P.’s case, it’s especially easy to draw a straight line from his escapist stories to the suffocating realities of his home life.“Herald’s family was very dysfunctional,” said Kitme Hardin, a sculptor based in LA who was one of H.P.’s closest friends from the age of nine. “He had a brother who was in and out of jail all the time. His father was an alcoholic who abandoned him. And his mother was flaky. So Herald had to bear the mantle of family leader… But he freed himself from that through his stories.” Real Deal covers for issues 1, 2, and 5—all featuring the book’s gangster-ass franchise character G.C. in the midst of creating hilarious, merciless mayhem.Of all the characters H.P. would create for the Real Deal universe, the antihero G.C. was the most essential, probably because he came from a dark and vengeful place that H.P. usually kept hidden from others.“G.C. was like Herald’s alter ego,” Lawrence said. “In real life, H.P. was a nice guy, he always worked a job and took care of business. But G.C. did what he wanted to do and didn’t give a shit. If G.C. wanted to shoot somebody, he’d just shoot them.”Still, Real Deal wasn’t just loose-cannon vigilante wish fulfillment. It represented a very specific reality, albeit a slightly twisted version of it. Some of the real-life stories relayed to me by Lawrence and Kitme were undoubtedly the basis for what can be found in Real Deal, only in the comic they end in bloodbaths instead of reminiscing laughter for times gone by.“The characters of Real Deal were always in a state of rage, and that’s how a lot of black men were at the time,” Lawrence said. “We weren’t going to back down or take any more shit. And that’s what happened in the LA Riots.”At first Herald and Lawrence tried to get Real Deal published through traditional channels, but no one bit. Unfortunately, Americans were and still are big, boring pussies and wouldn’t allow a comic book about rage-filled, homicidal black dudes slapping bitches and stomping pigs to be sold next to Spider-Man and Archie. So Lawrence and H.P. did the only reasonable thing left to do and self-published the first issue of Real Deal in 1989. The oversize comic book sold for two bucks a pop, its cover featuring G.C. brandishing a hand cannon while chasing some poor, soon-to-be-dead sucker. But even though the physical object had actually been printed and was now in their hands, the pair ran into distribution problems.Kitme remembers trying to get local shops to carry it: “A lot of it was racially based fear. At the beginning, people would push the thing back in my face. Like all great ideas, Real Deal was ahead of its time.”As the years went on and issues were eked out, H.P. and Lawrence were barely able to fund or even continue to create their beloved comic in their free hours. “There was a year or two between each issue because of money and time,” Lawrence said. “Days you’re working you don’t feel like drawing. You’re exhausted. And self-publishing ain’t cheap. We could’ve done ten issues a year if it wasn’t for our issues with money.”Despite Real Deal’s limited distribution and infrequency, it is considered an untainted paradigm for many comics artists. [Benjamin Marra](http:// Benjamin Marra | VICE), VICE contributor and creator of the ultraviolent Gangsta Rap Posse series, is still in awe: “I get depressed when I come across a comic like that because I feel I can’t achieve that level of success. Those comics are so awesome that I have trouble even looking at them. It’s some of the most inspiring stuff I’ve ever seen.”Johnny Ryan, a comic artist who once drew a story for VICE about a mystical janitor who feeds a prepubescent boy “dog syrup” and later takes the boy to canine heaven and feeds him to dogs, went even further with his praise of Real Deal: “It’s like a unicorn. It was an odd thing to find black artists making alternative nonsuperhero comics at that time, or any time. To have that voice was great, and it hasn’t been duplicated. It’s one of the best comics of the 90s.”The last issue of Real Deal appeared in 2001, and the reasons for its decade-long delay are tragic: In 1998, at the age of 43, H.P. suffered a stroke at the wheel of his car and died. To this day, Lawrence feels H.P’s body’s breakdown was the result of the burden he bore for his family.“The last year of his life, the stress of his family really got to him,” Lawrence said. “He started aging rapidly, and his hair turned gray. I remember this one time his brother had been thrown in jail, and his family was trying to pawn all of H.P.’s personal stuff to get him out, even though his brother had been in and out of jail since he was 14. Stuff like that happened constantly, and it was too much for H.P.”The palpable sense of rage and indignation that informed Real Deal still exists in a big way, and one could make the argument that it has spilled over into all races and creeds who feel disenfranchised or cheated. Just imagine the sorts of gory joy Lawrence and H.P. could have inserting G.C. and his crew into an Occupy rally. Unfortunately, it’s questionable whether the comic will return. Lawrence is now 51 and works as a security guard in LA, without a family who might support his more creative endeavors. Still, Lawrence continues to promise a seventh issue to me, fans, and himself. It could potentially inspire an entire generation to disregard political correctness or diplomacy and just throw hot coffee in cops’ faces. It could be just what we need.@WilbertLCooperLove funny books? Check these out:The Offensive ReviewNasty KidzAlan MooreNick Gazin's Comic Book Love-In

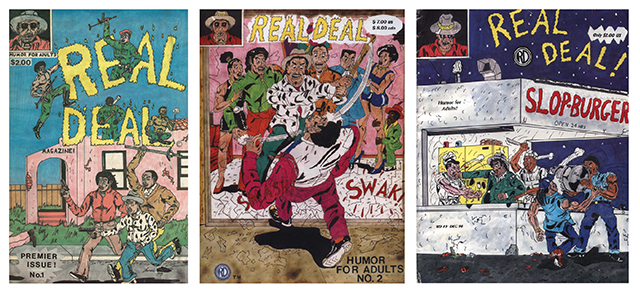

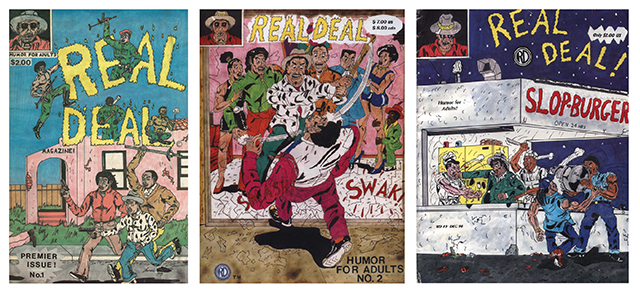

Real Deal covers for issues 1, 2, and 5—all featuring the book’s gangster-ass franchise character G.C. in the midst of creating hilarious, merciless mayhem.Of all the characters H.P. would create for the Real Deal universe, the antihero G.C. was the most essential, probably because he came from a dark and vengeful place that H.P. usually kept hidden from others.“G.C. was like Herald’s alter ego,” Lawrence said. “In real life, H.P. was a nice guy, he always worked a job and took care of business. But G.C. did what he wanted to do and didn’t give a shit. If G.C. wanted to shoot somebody, he’d just shoot them.”Still, Real Deal wasn’t just loose-cannon vigilante wish fulfillment. It represented a very specific reality, albeit a slightly twisted version of it. Some of the real-life stories relayed to me by Lawrence and Kitme were undoubtedly the basis for what can be found in Real Deal, only in the comic they end in bloodbaths instead of reminiscing laughter for times gone by.“The characters of Real Deal were always in a state of rage, and that’s how a lot of black men were at the time,” Lawrence said. “We weren’t going to back down or take any more shit. And that’s what happened in the LA Riots.”At first Herald and Lawrence tried to get Real Deal published through traditional channels, but no one bit. Unfortunately, Americans were and still are big, boring pussies and wouldn’t allow a comic book about rage-filled, homicidal black dudes slapping bitches and stomping pigs to be sold next to Spider-Man and Archie. So Lawrence and H.P. did the only reasonable thing left to do and self-published the first issue of Real Deal in 1989. The oversize comic book sold for two bucks a pop, its cover featuring G.C. brandishing a hand cannon while chasing some poor, soon-to-be-dead sucker. But even though the physical object had actually been printed and was now in their hands, the pair ran into distribution problems.Kitme remembers trying to get local shops to carry it: “A lot of it was racially based fear. At the beginning, people would push the thing back in my face. Like all great ideas, Real Deal was ahead of its time.”As the years went on and issues were eked out, H.P. and Lawrence were barely able to fund or even continue to create their beloved comic in their free hours. “There was a year or two between each issue because of money and time,” Lawrence said. “Days you’re working you don’t feel like drawing. You’re exhausted. And self-publishing ain’t cheap. We could’ve done ten issues a year if it wasn’t for our issues with money.”Despite Real Deal’s limited distribution and infrequency, it is considered an untainted paradigm for many comics artists. [Benjamin Marra](http:// Benjamin Marra | VICE), VICE contributor and creator of the ultraviolent Gangsta Rap Posse series, is still in awe: “I get depressed when I come across a comic like that because I feel I can’t achieve that level of success. Those comics are so awesome that I have trouble even looking at them. It’s some of the most inspiring stuff I’ve ever seen.”Johnny Ryan, a comic artist who once drew a story for VICE about a mystical janitor who feeds a prepubescent boy “dog syrup” and later takes the boy to canine heaven and feeds him to dogs, went even further with his praise of Real Deal: “It’s like a unicorn. It was an odd thing to find black artists making alternative nonsuperhero comics at that time, or any time. To have that voice was great, and it hasn’t been duplicated. It’s one of the best comics of the 90s.”The last issue of Real Deal appeared in 2001, and the reasons for its decade-long delay are tragic: In 1998, at the age of 43, H.P. suffered a stroke at the wheel of his car and died. To this day, Lawrence feels H.P’s body’s breakdown was the result of the burden he bore for his family.“The last year of his life, the stress of his family really got to him,” Lawrence said. “He started aging rapidly, and his hair turned gray. I remember this one time his brother had been thrown in jail, and his family was trying to pawn all of H.P.’s personal stuff to get him out, even though his brother had been in and out of jail since he was 14. Stuff like that happened constantly, and it was too much for H.P.”The palpable sense of rage and indignation that informed Real Deal still exists in a big way, and one could make the argument that it has spilled over into all races and creeds who feel disenfranchised or cheated. Just imagine the sorts of gory joy Lawrence and H.P. could have inserting G.C. and his crew into an Occupy rally. Unfortunately, it’s questionable whether the comic will return. Lawrence is now 51 and works as a security guard in LA, without a family who might support his more creative endeavors. Still, Lawrence continues to promise a seventh issue to me, fans, and himself. It could potentially inspire an entire generation to disregard political correctness or diplomacy and just throw hot coffee in cops’ faces. It could be just what we need.@WilbertLCooperLove funny books? Check these out:The Offensive ReviewNasty KidzAlan MooreNick Gazin's Comic Book Love-In

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

For his part, H.P. was fueled by an equally intense compulsion to write up these intensely absurd and homicidal doodle-stories starring G.C., becoming even more prolific once he realized Lawrence could turn them into technically impressive comics. It’s always tempting to psychoanalyze artists, but in H.P.’s case, it’s especially easy to draw a straight line from his escapist stories to the suffocating realities of his home life.“Herald’s family was very dysfunctional,” said Kitme Hardin, a sculptor based in LA who was one of H.P.’s closest friends from the age of nine. “He had a brother who was in and out of jail all the time. His father was an alcoholic who abandoned him. And his mother was flaky. So Herald had to bear the mantle of family leader… But he freed himself from that through his stories.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement