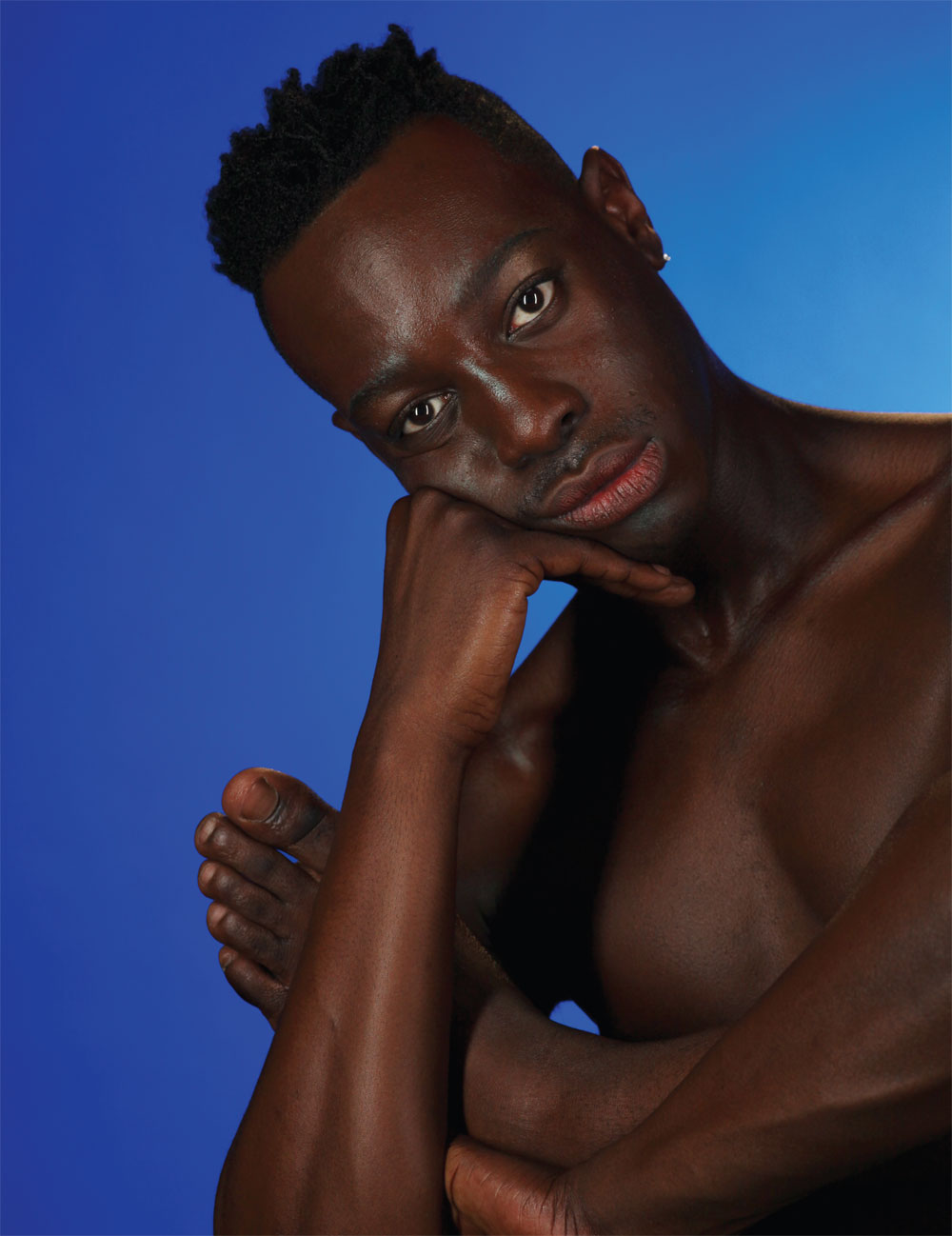

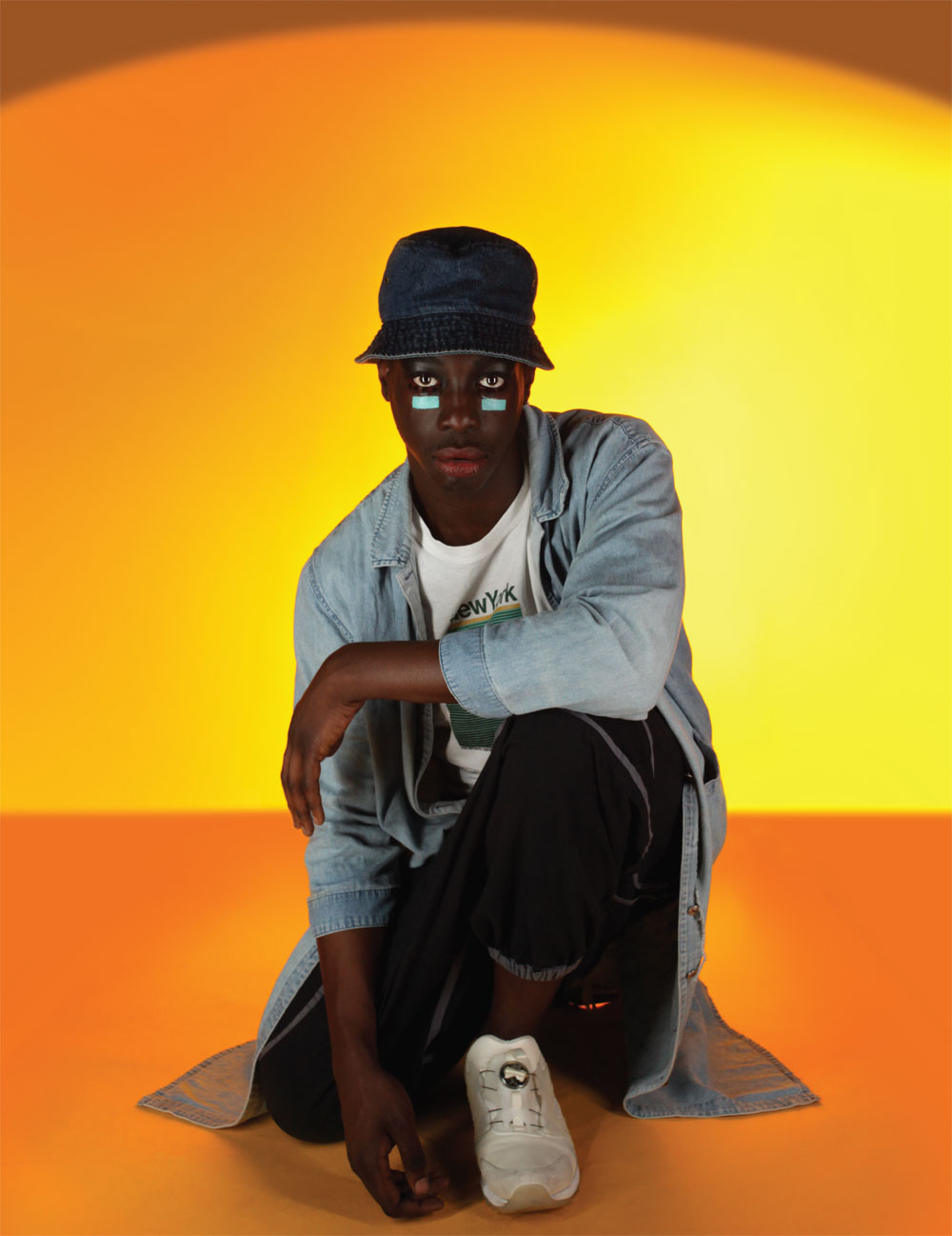

Photos by Matthew Leifheit, Styled by Stephanie Seibel, Makeup by Mara Capps

This article appears in the August Issue of VICE MagazineOn a day in June I sat in a small French café in the heart of Harlem waiting for the rapper Le1f to arrive. On a television screen above the bar, a local news channel reported the horrifying events of the previous evening: A white man spent an hour befriending black churchgoers during a prayer service at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in Charleston, South Carolina, before opening fire and killing nine of them in an act of white-supremacist terrorism. Around me, only a handful of couples and people having casual lunch meetings occupied the tables draped in cloth and butcher paper. The mood inside the restaurant was in contrast to the events unfolding. Most were, if not oblivious, too busy or occupied to be consumed with the news.

Advertisement

When Le1f finally glided into the dining room (like any good rising star, he was close to an hour late), he asked me how I was in a voice that seemed to address what had transpired the night before—a senseless act of violence against not just those innocent worshipers but black bodies everywhere."All this is pretty crazy," I said."I'm trying to keep up," Le1f offered.For many black Americans, the church is a second home. It was for me, and it was for Le1f, too. Our conversation about the Charleston shooting quickly turned to the role that religion plays in black American life. Le1f, whose given name is Khalif Diouf, was born to a Muslim father and a Methodist mother. Although he grew up not far from the café in upper Manhattan, he spent his summers in Yemassee, South Carolina, a town of fewer than 1,000 people in the state's Low Country, about an hour's drive inland from Charleston. Despite the town's small size and the lack of much to do in the mucky heat, Yemassee became an influential stop in his personal growth. More than 50 percent of the town's population is black, and since pretty much the only thing he had to do there was go to church, he spent his days putting on performances with his cousin Ebony. The two would spend all day making raffia skirts and costumes out of tissue paper used for Kwanzaa gifts. "That's all I ever got to do," he said, "put on performances and go to church."

Advertisement

In church, he got his first inkling to question the world around him. He didn't understand the need to dress up to "hear these stories," and he didn't understand why so many black Americans practiced Christianity at all. "Why are we following the rules of someone who followed someone who followed someone who translated this and then who taught it all to our ancestors on a slave ship?" he asked.

You might be surprised to hear Le1f's nuanced questioning and reflection on these issues if you hadn't listened to his music closely. Though driven by infectious and heady beats made for a nightclub, his songs have always slyly engaged politics. His debut album, Riot Boi, to be released by XL Recordings this fall, features some of the hottest electronic producers working right now—SOPHIE, Evian Christ, Dubbel Dutch—while tackling issues like trans acceptance and racial injustice. "I still want to make the music I want to listen to. I still want to make Rich Homie Quan and Beyoncé songs," he said. "I just want them to be about other issues."His songs force the listener to engage first with the movement the beat creates in order to connect to the root message. His voice is low and his flow rapid-fire, like an avant-garde Busta Rhymes. His sound is striking not just for its speed but also for its depth, since most popular contemporary rappers—Drake, Kendrick Lamar, Young Thug—operate in a higher vocal range.

Advertisement

Le1f originally gained recognition in 2009 as a producer on songs like Das Racist's "Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell." That track was silly and memorable for its lyrics as well as its production. The beat was repetitive, with variation building slowly with warbled samples and vocal manipulations. Most notably, the synths were stark and off-kilter, a sound that would soon become Le1f's signature. The track came out in a weird, in-between period for rap music and electronic music, which weren't at the peak levels they've reached in the mainstream in the past five years. Le1f's first productions were a precursor to the progressive sonic aesthetics that now dominate both genres.Le1f didn't come into his own as a rapper until three years later, with the release of his debut mixtape, Dark York, in 2012, at a time when a new class of avant-garde black performers, many of them queer, was coalescing. Azealia Banks, Mykki Blanco, and Zebra Katz had captured attention for lyrically dense singles coupled with complex, genre-smashing personal imagery. In "Wut," the mixtape's viral lead single, produced by 5kinAndBone5, Le1f raps, "I'm getting light in my loafers," quickly getting him dubbed "the gay rapper." While Le1f has never shied away from presenting his sexuality in his music, it's been a limiting term—one that asks him to place his sexuality first in his music and attempts to distinguish him from mainstream rap.

Advertisement

Le1f is gay and raps about being gay, but he's not a gay rapper. The "gay rap" for which Le1f has become known is far more complicated than the term allows. It centers on challenging the power and destruction of the male gaze and the fetishization of his black body by white men. The video for "Wut" is a visual feast of bodies—young black and brown women in heels and sneakers, Le1f dancing and making silly faces in acid-washed short shorts. One of the most intriguing bodies is anonymous: a white man, wearing only a pair of black shorts and a Pikachu mask, seated casually in a chair. His muscled body is oiled and gleaming. Le1f sits on his lap as he raps to the camera: "He really wanna cuddle / The fever in his eyes, he wanna suckle on my muscle / He wanna burst my bubble and see what's in my jungle / A Christopher Columbo fumbles, how's that cookie crumbled?"The scene is campy yet powerful. We see a fully clothed Le1f assume a position of power. His black body, typically the object of derision, brutality, and control, is instead the controller of the gaze. In the song, he observes the direction of the white male gaze; in the video, he takes it away. Le1f usurps the common tropes—the masculine white gay male as the representation of homosexuality, the over-the-top heterosexuality of the hip-hop world—and brings us something new and radical. A lyric from his song "Hey" exemplifies his steadfast commitment to representing his too-often ignored position: "Ask a gay question / Here's a black answer."

Advertisement

With Riot Boi, Le1f is furthering his commitment to making music that tackles complex issues. "I had a list of topics in my Google Docs since I was sixteen," he told me. "Like a bullet-point list of social issues—well, not social issues, just things I wanted to talk about." For Le1f, it's natural that all these things should come together in one record. "There's definitely an overarching theme of knowing what's going on in the world around you and respecting it," he said. "It's a very pro-trans, pro–clean water, Black Lives Matter record."About a year after the deadline passed, Le1f turned the album in to his label in the spring. "I've just been a snob, and an over-expender about it," he said. But the indecision came with good reason. He was narrowing 20 tracks down into a digestible debut album, determined to make a splash after building up his reputation on the internet and in the underground for so many years.After our lunch, Le1f called an Uber to take us to his local barbershop, on 134th Street and Frederick Douglass Boulevard. He was performing the next day at the Firefly Music Festival, in Dover, Delaware, and he wanted to get a fresh fade before we headed out of town later that afternoon. The space was like any other black-owned barbershop in other cities in the country. The floor was covered in patches of freshly shorn hair needing to be swept away, and men, young and old, filled the big barber chairs.

Advertisement

Le1f's barber was the only woman working in the shop. He started to go to her because of her design skills, but he'd kept seeing her out of a sense of loyalty. He felt partially responsible after she lost her position at a different barbershop. When she was out once, he had his hair cut by a male barber there, and the next time he went in the male barber insisted that Le1f was his client. "The boss manager dude was calling her all kinds of bitches and dykes, and she was like, 'Not today.'" She walked out, and Le1f followed her to her new place. He felt it was necessary to support her after she had been dismissed or "homophobically fired," as he put it.After his fade, Le1f and I went to the apartment that he shares with his best friend, the painter and rapper DonChristian Jones. Despite his growing fame, Le1f, Jones, and their roommate live like many other young people. Their apartment is angular, dark, and awkwardly laid out. Because it's on the ground level, the roar of the city—a symphony of ambulance sirens and playful arguments between neighbors—filtered in through the windows and inserted itself into our conversation. Le1f and Jones seemed oblivious to the noise.The two met in college, at Wesleyan University, in Connecticut. Jones was studying to be a painter, and Le1f was there to study ballet and modern dance. He had been dancing since he was four years old, when he began training with the Dance Theatre of Harlem. In high school, Le1f left the Dance Theatre's program to attend the Concord Academy, a boarding school in Massachusetts. Although the Dance Theatre provided him with a sturdy dance foundation, he left in large part because he wanted to "study more than just ballet."

Advertisement

"There wasn't any room for any kind of, like, bodies," he told me of the program's strict adherence to classical forms. "There wasn't the whole sense of bodies inherently being able." At Wesleyan, he continued to study dance. He and Jones lived in Eclectic House, a residential society for the university's musicians and other artists. He began to make beats for the society's dance happenings and grew to love it. "I feel like I have an ear for production," he said. "Probably better than I do have an ear for some other things." He learned not by putting together melodies but by downloading samples, piecing them together in random arrangements, and deleting the "ugly" notes.After school, he moved back home to New York and pursued music. Although his studies had focused on dance, he knew that he wanted to be some sort of vocalist. "Taking modern dance in high school does not lead to good raps," he joked. His academic and dance-production efforts were the true jumping-off point for his transition to rap. Dance—and movement—remains central to what Le1f does. It informs what it is to be an individual listening to his music. It's about bodies "inherently being able," having the right to do what they want, where they want, regardless of what others deem normal or acceptable.

Le1f's musical dreams really began when he was a teenager, after he heard Dizzee Rascal's debut grime album, Boy in da Corner. When Dizzee's second album, Showtime, came out, he checked out his label, XL Recordings. On their website, he found a list of their artists, including a young rapper from London, M.I.A. "That was the summer of my life," he said, about discovering M.I.A. and the video for her first single, "Galang." "That was kind of when I decided I was going to be a performer in that way," he said. In M.I.A., he found an artist who made it cool to talk about sociopolitical issues. "I think it's more effective to slip it under," he said."Riot Bio is a very pro-trans, pro–clean water, Black Lives Matter record." – Le1f

Advertisement

Because Le1f is so frequently on the road, his room is a mess, still covered in clear plastic bags full of clothing from the third roommate's recent bedbug scare. (On one Riot Boi track he raps, "My room's a mess because designers keep on giving me gifts.") Jones's bedroom was covered in clothes, shoes, and remnants of weed, but we hung out in there as the two prepared for the drive to Delaware. Le1f took a hit of an already lit joint. Next to an assorted bunch of clothes was a pile of rolled-up canvases from Jones's university thesis. He showed me a handful of oil paintings featuring friends while we listened to a playlist of remixes and originals from contemporary artists like Dre Green. Jones saved his best canvas for last: an almost life-size oil and acrylic painting of Le1f titled Bitches Say I'm Tacky Daddy. In it, Le1f looks visibly younger, with a thinner face and a slighter body, but his essence is entirely present. He has a hand perched on his hip, the other poised in the air, resting on his shoulder. He wears a colorful tank top, and his eyes are staring straight on, penetrating in their determination. All the evidence of his drive is visible in that look.

On the afternoon of his show at the Firefly Music Festival, Le1f mostly ignored the bottled water and fruit trays in the little outdoor hut that had been set up as a makeshift artist's green room. Instead he shared a joint with Jones and Javas Ganguly, a.k.a. DJ Javascript, a longtime friend. The joint was the first step in Le1f's pre-show ritual, which also includes stretching his limbs as if he's warming up to play a sport.

Advertisement

"I do more stretches than vocal warm-ups," he said. "Learning how to perform as not-a-dancer is still something I'm trying to do." A group of men in their 20s working as festival staff looked on, first giggling, then silent, as Le1f crossed his arms behind his legs, stood up, and arched his neck back. He let his smooth face take in the breeze and the few stray glimpses of sun peeking through the overcast sky. He then let his arms hang limp and heavy at his side, before popping up, ready to take the stage.For the performance, Le1f wore a pair of ratty, mud-covered black boots and a loose black singlet made of swimsuit material that ended just above his knees. On his head he wore a dizzying and beautifully adorned black baseball cap that hid his new fade. A crown of fabric roses and pinches of gold lace trimmed the brim above blue fringes that ran down the sides of his face. The onstage costume was built to move, and movement is the backbone of Le1f's performing life. "The function for me is, do I have the ability to move the way that I want to move and dance the way that I want to dance?" he said. "Anything that happens when someone is watching is a performance. If you roll your neck at somebody, that's a performance. If you wear anything, that's a performance."Le1f draws inspiration for his stage presence from artists like M.I.A. and Grace Jones, whose brash physicality made them instantly iconic. Jones's figure—her strong, sleek, athletic body and the ways in which she maneuvers it both onstage and in the world around her—informs his own artistry. "The fact that your body is corporeal, it's real, it's a shape, it's a color, it's a texture, and so are fabrics, you know—I feel like that is such a big thing that influenced fashion and how I dress when I'm onstage."Grace Jones was a touchstone for Le1f in another way—for her rich mahogany skin. "I feel like there are people who come along—like, celebrities who come along—and make a look attractive: not a fashion look, an actual facial structure, a complexion, a race, a genetic makeup. They make it beautiful. And I think Grace Jones did that." An Evian Christ–produced song on Riot Boi, "Grace, Alek, or Naomi," celebrates dark-skinned women like Jones, Alek Wek, Naomi Campbell, Ataui, and Ajak Deng. The song is in praise of their rich beauty as well as his own."Umami," another new track, celebrates a different black woman, the artist and DJ Juliana Huxtable. A friend of Le1f's, Huxtable was born intersex and assigned to the male gender at birth. "I like that she's cool cuz she loves her body," he raps. For the video, Le1f hopes to feature a number of famous transgender women, like Huxtable, the model and actress Hari Nef, and the artist Kia LaBeija, posed like the characters in classic paintings.

As Le1f performed these new songs onstage, a crowd began to swell. When the pop synths of a new track called "Koi" started to build, a teenage boy in a '96 Dream Team jersey ran up to the stage. Although the song hasn't been released yet, it's gained a following through the quick clips Le1f has posted to his Instagram account. "This is the one that's going to blow up," DonChristian Jones told me in the wings. "You wanna get to know me / Wanna be my homie / I just came to party / Not here for you boy," Le1f sings on the track. The song, produced by the PC Music DJ SOPHIE, is a weird mash-up of pop and EDM. "It's about a boy" was all that Le1f would say about it. He was being coy about "Koi."Le1f the performer, in all of his manifestations as rapper and dancer and artist, is the real draw. "Koi" live exemplified this. Le1f danced across the stage, gyrated, vogued, and gripped the mic like every next word was more important than the last. To watch him perform was to watch grace, fury, and passion in action. It was mesmerizing and invigorating. The audience too felt the power as they jumped and clapped along to the beat, which is maybe the best thing SOPHIE has produced yet. Like any great PC Music song (meaning, like any great pop song), you know what's good when you hear it.Still, I don't think SOPHIE deserves all the credit here. A beat becomes a song with the right touch, whether through production or performance or lyrics. With "Koi" specifically and Le1f generally, we see all of these components come together. You will never forget what he looks like, or who he is, or what he says. And right now, the world could use more figures like that."Anything that happens when someone is watching is a performance. If you roll your neck at somebody, that's a performance. If you wear anything, that's a performance."