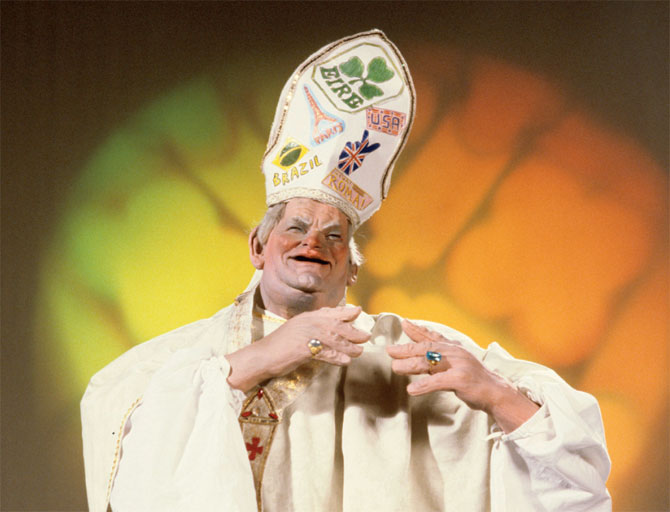

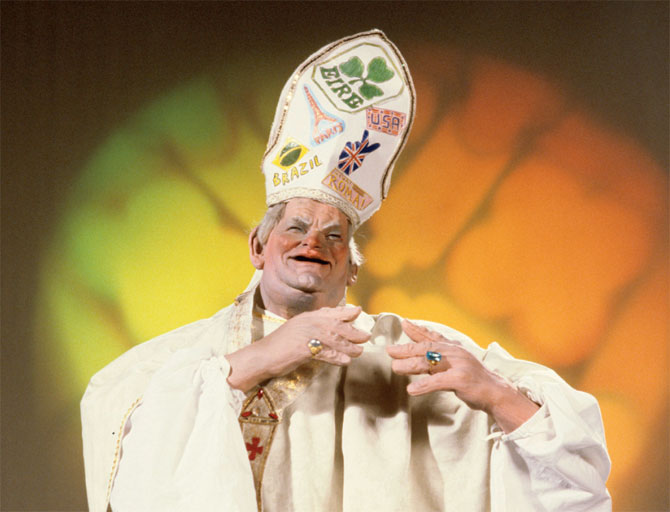

WORDS BY ALEX GODFREYPHOTOS COURTESY OF SPITTING IMAGE In the 1980s, when there were only four channels on British TV, EVERYBODY would sit down to watchSpitting Imageat 10 PM on a Sunday night. At its peak, it was getting 15 million viewers per episode. Producer John Lloyd, fresh off the success of satirical sketch showNot the Nine O’Clock News, was at the reins, marshalling a team that boasted some of the most creative, talented and funniest people in the UK. A weekly puppet show containing equal amounts of satire and slapstick,Spitting Imageripped into politicians, sports stars and celebrities, with a team tirelessly working up to the last minute to make it as topical as humanly possible.When the show began in February 1984, the political landscape was ripe for satire. Thatcher’s second government was in full flow, the miners were about to strike, and Reagan was US president. Thatcher was portrayed as a tyrannical horror who pissed in urinals and took advice from Hitler. The Queen Mother became a senile northern drunk.Peter Fluck and Roger Law met at the Cambridge School of Art in the mid-1950s. Both were illustrators and political cartoonists before teaming up in 1975 to make 3D caricature models which would be photographed for magazines and newspapers. In 1981 they were approached by television graphic designer Martin Lambie-Nairn about making a TV show. Teaming up with John Lloyd,National Lampoon’s Tony Hendra (who went on to play Spinal Tap’s manager Ian Faith) and documentary producer Jon Blair, they finally unleashedSpitting Image, making the puppets in a warehouse in Canary Wharf, before sending them to be shot in Birmingham for Central Television.Writers on the show includedPrivate Eye’s Ian Hislop and Nick Newman, and Rob Grant and Doug Naylor (later ofRed Dwarf), while voice artists included (among others) Harry Enfield and Steve Coogan. A young Chris Cunningham worked on the puppets. The plug was finally pulled in 1996, and although it was nearly resurrected a few years ago (and is sorely missed) maybe it’s best left alone.Spitting Imagewas made by fantastically passionate people with fire in their bellies. We spoke to three of them about it.JOHN LLOYDJohn Lloyd spent his 20s as a successful BBC radio producer, and worked with Douglas Adams on the first radio series ofThe Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxybefore moving to TV to head upNot the Nine O’Clock News. After three years of that he launchedSpitting Image, and went on to concentrate onBlackadder, producing all four series. He spent the 1990s directing TV ads and in 2003 created Stephen Fry’s BBC panel showQI, which is now in its eighth series.Vice: Were you still on Not the Nine O’Clock News when Spitting Image reared its head?John Lloyd:Well, first of all,Spitting Imagewasn’t just one idea, because any fool can have an idea—it’s doing it that’s the difficult bit. Tens of thousands of brilliant individual decisions made it what it was. You could see when they did that awful CGI version that they called the newSpitting Image—did you see that? I can’t remember what it was called.Headcases [2008]. It was dreadful.Yeah, it was just awful. It had no attitude, nobody cared. It was just people trying to make money out of a format. So, I had come from radio in ’79 to makeNot the Nine O’Clock Newsand I knew a lot of brilliant voiceover people and great writers. And Sean Hardie, the producer ofNot the Nine O’Clock News, wanted to do something that had a strong contemporary base, and puppets occurred to us straight away. That was when I first met Roger Law, in ’79. I went to him and asked him if he could build puppets, because he used to do these wonderful magazine covers with Peter Fluck. And he said, “I’ve never made a fucking puppet. How much money have you got?” And I said, “About £200,” and he laughed for about ten minutes and said, “Don’t be ridiculous.” So we got the BBC props department to make these puppets cast out of Jablite, which is this expanded polystyrene foam stuff, and they were operated with coat hangers, they were absolutely hopeless. They didn’t really look like the people, and we got the voices good but it didn’t really happen. We dumped them after one or two episodes. But in ’82 or so, Martin Lambie-Nairn, the graphics bloke who invented the Channel 4 logo, had an idea for a puppet show and put up the first £10,000, which went in five minutes, wasted on trying to work out how to do it. Then Clive Sinclair, the computer whiz, who was a Cambridge guy I knew slightly, put up £60,000. That all went on a single puppet of Nancy Reagan which for some reason was done as a parrot. I heard about this and rushed over to Roger and said, “I’m probably the only person in the world who can do this.” People had done satire on telly before, shows likeThat Was the Week That Was, but because shows like that were topical, it was thought you couldn’t possibly have sets, you just had to get on and say the lines. And people had done high-density comedy that moved very fast, likeMonty Python, but nobody had ever done the two together, and that was the whole idea ofNot the Nine O’Clock News: something as visually rich asPython, but as sharp and up-to-the-minute asThat Was the Week That Was. It was a hell of a steep learning curve. There were so many tricks we’d learned. So I begged Roger to let me do it.You were initially turned down by a few production companies, including LWT, Thames and Channel 4. Was that because they didn’t have the foresight to see what you had?There were a number of reasons. We had very few selling tools. We basically had a bunch of postcards from Fluck and Law’s print work, and an idea, and quite a cool cast list, because Tony Hendra was very famous in America, and I had just doneNot the Nine O’Clock News, which was a huge success that got good reviews and ratings. So we had that and we had this half-baked puppet of Nancy Reagan, when it worked. But we didn’t really get anywhere, because although it seems obvious now—puppets and politics—they were all stuck on the idea that puppets must be children’s stuff. We said it was a late-night thing for grown-ups, but nobody got it until we went to see Charles Denton at Central, a proper programme maker with a great track record, and he got it straight away. Then we did two pilots, I think one with our own money, and then one for Central, and he commissioned 22 episodes. We had to beat him down to 13, which we could just about survive doing if we had a three-week break in the middle. That was the beginning of ’84, and it predictably got terrible reviews for the first show.Why predictably?Well, it’s always the same.Blackadderwas very badly reviewed,Not the Nine O’Clock Newshad terrible reviews—theGuardiansaid, “As forNot the Nine O’Clock News— they’re a bunch of wankers.” Can you imagine anyone saying that in theGuardiantoday? So I’m used to the idea that if something’s really innovative, everyone thinks it’s rubbish. Compared to how successful it became a few years later, it was very rough at the edges, but it did have that thing you can’t fake, which is freshness and anger, and it was so dark and strange. There was one sketch about an old people’s home for ex-prime ministers where they were punished for all the terrible things they’d done to the country by having their faces shoved in soup bowls and having their ties cut off by the nurse, that sort of thing. In the middle ofSpitting Image, a constant criticism, especially from politicians, was: “Brilliant puppets, absolutely terrible, unfunny scripts.” Which was their way of getting at us. But I had this letter from a blind woman, who said, “I don’t understand. My husband tells me people are criticisingSpitting Imagein the papers for not being funny, and I think it’s the funniest programme on television; I ‘watch’ it every week.” And it was a brilliant radio show, but because the puppets were so striking, your visual sense was so overloaded you didn’t really listen to what was happening, you just saw puppets hitting each other. We had wonderful writers, the scripts and voices were great. There were three producers by that time: Tony Hendra fromNational Lampoon, Jon Blair, who was a factual producer from Thames, me, and Fluck and Law. Hendra would produce the scripts, Blair would do the money and the logistics, I would do all the crazy stuff, actors and voices, and Fluck and Law did the puppets. So it was very, very unwieldy, it was very hard to make a decision.

In the 1980s, when there were only four channels on British TV, EVERYBODY would sit down to watchSpitting Imageat 10 PM on a Sunday night. At its peak, it was getting 15 million viewers per episode. Producer John Lloyd, fresh off the success of satirical sketch showNot the Nine O’Clock News, was at the reins, marshalling a team that boasted some of the most creative, talented and funniest people in the UK. A weekly puppet show containing equal amounts of satire and slapstick,Spitting Imageripped into politicians, sports stars and celebrities, with a team tirelessly working up to the last minute to make it as topical as humanly possible.When the show began in February 1984, the political landscape was ripe for satire. Thatcher’s second government was in full flow, the miners were about to strike, and Reagan was US president. Thatcher was portrayed as a tyrannical horror who pissed in urinals and took advice from Hitler. The Queen Mother became a senile northern drunk.Peter Fluck and Roger Law met at the Cambridge School of Art in the mid-1950s. Both were illustrators and political cartoonists before teaming up in 1975 to make 3D caricature models which would be photographed for magazines and newspapers. In 1981 they were approached by television graphic designer Martin Lambie-Nairn about making a TV show. Teaming up with John Lloyd,National Lampoon’s Tony Hendra (who went on to play Spinal Tap’s manager Ian Faith) and documentary producer Jon Blair, they finally unleashedSpitting Image, making the puppets in a warehouse in Canary Wharf, before sending them to be shot in Birmingham for Central Television.Writers on the show includedPrivate Eye’s Ian Hislop and Nick Newman, and Rob Grant and Doug Naylor (later ofRed Dwarf), while voice artists included (among others) Harry Enfield and Steve Coogan. A young Chris Cunningham worked on the puppets. The plug was finally pulled in 1996, and although it was nearly resurrected a few years ago (and is sorely missed) maybe it’s best left alone.Spitting Imagewas made by fantastically passionate people with fire in their bellies. We spoke to three of them about it.JOHN LLOYDJohn Lloyd spent his 20s as a successful BBC radio producer, and worked with Douglas Adams on the first radio series ofThe Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxybefore moving to TV to head upNot the Nine O’Clock News. After three years of that he launchedSpitting Image, and went on to concentrate onBlackadder, producing all four series. He spent the 1990s directing TV ads and in 2003 created Stephen Fry’s BBC panel showQI, which is now in its eighth series.Vice: Were you still on Not the Nine O’Clock News when Spitting Image reared its head?John Lloyd:Well, first of all,Spitting Imagewasn’t just one idea, because any fool can have an idea—it’s doing it that’s the difficult bit. Tens of thousands of brilliant individual decisions made it what it was. You could see when they did that awful CGI version that they called the newSpitting Image—did you see that? I can’t remember what it was called.Headcases [2008]. It was dreadful.Yeah, it was just awful. It had no attitude, nobody cared. It was just people trying to make money out of a format. So, I had come from radio in ’79 to makeNot the Nine O’Clock Newsand I knew a lot of brilliant voiceover people and great writers. And Sean Hardie, the producer ofNot the Nine O’Clock News, wanted to do something that had a strong contemporary base, and puppets occurred to us straight away. That was when I first met Roger Law, in ’79. I went to him and asked him if he could build puppets, because he used to do these wonderful magazine covers with Peter Fluck. And he said, “I’ve never made a fucking puppet. How much money have you got?” And I said, “About £200,” and he laughed for about ten minutes and said, “Don’t be ridiculous.” So we got the BBC props department to make these puppets cast out of Jablite, which is this expanded polystyrene foam stuff, and they were operated with coat hangers, they were absolutely hopeless. They didn’t really look like the people, and we got the voices good but it didn’t really happen. We dumped them after one or two episodes. But in ’82 or so, Martin Lambie-Nairn, the graphics bloke who invented the Channel 4 logo, had an idea for a puppet show and put up the first £10,000, which went in five minutes, wasted on trying to work out how to do it. Then Clive Sinclair, the computer whiz, who was a Cambridge guy I knew slightly, put up £60,000. That all went on a single puppet of Nancy Reagan which for some reason was done as a parrot. I heard about this and rushed over to Roger and said, “I’m probably the only person in the world who can do this.” People had done satire on telly before, shows likeThat Was the Week That Was, but because shows like that were topical, it was thought you couldn’t possibly have sets, you just had to get on and say the lines. And people had done high-density comedy that moved very fast, likeMonty Python, but nobody had ever done the two together, and that was the whole idea ofNot the Nine O’Clock News: something as visually rich asPython, but as sharp and up-to-the-minute asThat Was the Week That Was. It was a hell of a steep learning curve. There were so many tricks we’d learned. So I begged Roger to let me do it.You were initially turned down by a few production companies, including LWT, Thames and Channel 4. Was that because they didn’t have the foresight to see what you had?There were a number of reasons. We had very few selling tools. We basically had a bunch of postcards from Fluck and Law’s print work, and an idea, and quite a cool cast list, because Tony Hendra was very famous in America, and I had just doneNot the Nine O’Clock News, which was a huge success that got good reviews and ratings. So we had that and we had this half-baked puppet of Nancy Reagan, when it worked. But we didn’t really get anywhere, because although it seems obvious now—puppets and politics—they were all stuck on the idea that puppets must be children’s stuff. We said it was a late-night thing for grown-ups, but nobody got it until we went to see Charles Denton at Central, a proper programme maker with a great track record, and he got it straight away. Then we did two pilots, I think one with our own money, and then one for Central, and he commissioned 22 episodes. We had to beat him down to 13, which we could just about survive doing if we had a three-week break in the middle. That was the beginning of ’84, and it predictably got terrible reviews for the first show.Why predictably?Well, it’s always the same.Blackadderwas very badly reviewed,Not the Nine O’Clock Newshad terrible reviews—theGuardiansaid, “As forNot the Nine O’Clock News— they’re a bunch of wankers.” Can you imagine anyone saying that in theGuardiantoday? So I’m used to the idea that if something’s really innovative, everyone thinks it’s rubbish. Compared to how successful it became a few years later, it was very rough at the edges, but it did have that thing you can’t fake, which is freshness and anger, and it was so dark and strange. There was one sketch about an old people’s home for ex-prime ministers where they were punished for all the terrible things they’d done to the country by having their faces shoved in soup bowls and having their ties cut off by the nurse, that sort of thing. In the middle ofSpitting Image, a constant criticism, especially from politicians, was: “Brilliant puppets, absolutely terrible, unfunny scripts.” Which was their way of getting at us. But I had this letter from a blind woman, who said, “I don’t understand. My husband tells me people are criticisingSpitting Imagein the papers for not being funny, and I think it’s the funniest programme on television; I ‘watch’ it every week.” And it was a brilliant radio show, but because the puppets were so striking, your visual sense was so overloaded you didn’t really listen to what was happening, you just saw puppets hitting each other. We had wonderful writers, the scripts and voices were great. There were three producers by that time: Tony Hendra fromNational Lampoon, Jon Blair, who was a factual producer from Thames, me, and Fluck and Law. Hendra would produce the scripts, Blair would do the money and the logistics, I would do all the crazy stuff, actors and voices, and Fluck and Law did the puppets. So it was very, very unwieldy, it was very hard to make a decision. Were there egos flying around, or was it a more restrained competitiveness?Well, it was very difficult. The hours were completely ludicrous. We had part of a banana warehouse on Canary Wharf, called Limehouse Studios. It was before Docklands had been regenerated. There wasn’t even a road when we first went there, it was a muddy track, and the warehouse had broken windows. We didn’t know what we were doing, and we were working with these fantastically dangerous chemicals, trying to work out the right kind of latex and so on. And everybody in those days drank and smoked and generally misbehaved. A lot of fighting went on. Nobody believed anybody else. The puppeteers had never made television and thought things could be done a certain way, and I was saying we couldn’t. And Hendra was a bit of a wild card and eventually had to be elbowed out.Why?He was sleeping in the office, indulging in far too many beers and God knows what else. He just wasn’t really coping with it, and he was a difficult person. We’ve long since made it up, I have to say, and you look back and are more forgiving, but we had no common ground. He was a magazine editor, I was a television comedy producer, and Blair was a documentary man, so trying to discuss whether a script was funny between that lot and blokes who made models, well, we just disagreed about everything. Nothing was getting done and I had to wrest control of it. There were too many chiefs. I’m not going to go into what his habits were, I’m sure we were all appallingly behaved, but people were in those days. You go to the modern BBC and there are health bars and juice bars and a handbag shop and fresh coffee. People in those days basically survived on cigarettes and whiskey most of the time, and a cheese roll every two days. There was no money, life was incredibly inspiring and good fun. But on the days when you’d go to a shoot, union rules said that crews had to have a three-course lunch with wine. The idea that anyone would drink at lunchtime now, legally, is completely out of the question. It was wild, we stayed up far too late, we all drank far too much, and eventually something had to be done because we couldn’t make decisions. So Hendra went back to the States.I did read somewhere about the time Roger threw a sofa at you while you were arguing about how to approach the miners’ strike.Yes. I think it was an armchair. It definitely was a chair. It was in the bar at Central Television. We all thought we should take the miners’ cause, because Channel 4 was the only other media outlet where they got even a hearing. My idea was that they should have had a ballot, and he just got cross. Roger hasn’t drunk for years, but in those days it would be like going to a bar with Rasputin; this great hand around an enormous flagon of ale. And we were all getting by on three hours sleep, because that was the only way to do it. If somebody wanted a puppet of Barry McGuigan, we had to stay up till four in the morning and do it.Was it like that for the whole three or four years you were there?No, human stamina’s got limits, but the first year was extremely difficult and there was nothing topical at all because it had all been written a week before. We managed to get in the Derby winner as a voiceover and we were so excited, because that had happened the day before it aired. People, especially sound guys, were doing 36-hour shifts just to get the thing done. It was completely mad. Eventually we learnt how to do it quickly and it started to be possible—by the end of the third series we were getting six or seven minutes of topical stuff all written the day before, and it was enormous fun.It was very successful by that point as well.It was huge. The third show in the third series got 15 million viewers and it was the number two programme in the country that week. It had something for everyone. Some people would watch it for the football jokes, some would watch it for the politics. My dad, who was in the Navy, asked me to dinner with all these old admirals and captains, naval commanders, and they all watched it because they hated Michael Heseltine for all the cuts they were pushing through. There were stories about Prince Andrew and Fergie being big fans. Andrew used to have the show flown out by helicopter to his ship so he could watch it.One of my enduring memories was the Prince Andrew centrefold in the middle of the Spitting Image book, him lying naked with a string of sausages covering his modesty.We loved doing that book. How cheeky was that? After I quit in despair in ’86, because I was so tired and overworked, I went to Romania to do a programme, and the tourist bloke, this amazing charming cultured person, had somehow got hold of that book, and to him it was like the Bible, a revered document, because you couldn’t say any of these things in Romania. He almost knelt down and asked me to bless him. He said, “This is modern Jonathan Swift, it’s so brilliant.”I used to watch the show with my parents on Sunday night, even though I was too young to get a lot of the jokes. Were you proud of the fact that kids watched it, that it appealed to everyone?Yes. At the time, most of my friends in their early 30s thought I’d gone completely mad and that I’d made a terrible mistake. But the fortunes of all the programmes I’ve ever done were made by 15-year-olds really, because eventually they’d say to their mum and dad, “You’ve got to watch this.” It’s a sort of iron rule to me that the audience are much more intelligent than most people give them credit for, and if you tell something truthfully you can read it on all sorts of levels. My kids likeSouth ParkandFamily Guy, and you don’t need to know every reference to feel that it’s right. It has a feel about it.

Were there egos flying around, or was it a more restrained competitiveness?Well, it was very difficult. The hours were completely ludicrous. We had part of a banana warehouse on Canary Wharf, called Limehouse Studios. It was before Docklands had been regenerated. There wasn’t even a road when we first went there, it was a muddy track, and the warehouse had broken windows. We didn’t know what we were doing, and we were working with these fantastically dangerous chemicals, trying to work out the right kind of latex and so on. And everybody in those days drank and smoked and generally misbehaved. A lot of fighting went on. Nobody believed anybody else. The puppeteers had never made television and thought things could be done a certain way, and I was saying we couldn’t. And Hendra was a bit of a wild card and eventually had to be elbowed out.Why?He was sleeping in the office, indulging in far too many beers and God knows what else. He just wasn’t really coping with it, and he was a difficult person. We’ve long since made it up, I have to say, and you look back and are more forgiving, but we had no common ground. He was a magazine editor, I was a television comedy producer, and Blair was a documentary man, so trying to discuss whether a script was funny between that lot and blokes who made models, well, we just disagreed about everything. Nothing was getting done and I had to wrest control of it. There were too many chiefs. I’m not going to go into what his habits were, I’m sure we were all appallingly behaved, but people were in those days. You go to the modern BBC and there are health bars and juice bars and a handbag shop and fresh coffee. People in those days basically survived on cigarettes and whiskey most of the time, and a cheese roll every two days. There was no money, life was incredibly inspiring and good fun. But on the days when you’d go to a shoot, union rules said that crews had to have a three-course lunch with wine. The idea that anyone would drink at lunchtime now, legally, is completely out of the question. It was wild, we stayed up far too late, we all drank far too much, and eventually something had to be done because we couldn’t make decisions. So Hendra went back to the States.I did read somewhere about the time Roger threw a sofa at you while you were arguing about how to approach the miners’ strike.Yes. I think it was an armchair. It definitely was a chair. It was in the bar at Central Television. We all thought we should take the miners’ cause, because Channel 4 was the only other media outlet where they got even a hearing. My idea was that they should have had a ballot, and he just got cross. Roger hasn’t drunk for years, but in those days it would be like going to a bar with Rasputin; this great hand around an enormous flagon of ale. And we were all getting by on three hours sleep, because that was the only way to do it. If somebody wanted a puppet of Barry McGuigan, we had to stay up till four in the morning and do it.Was it like that for the whole three or four years you were there?No, human stamina’s got limits, but the first year was extremely difficult and there was nothing topical at all because it had all been written a week before. We managed to get in the Derby winner as a voiceover and we were so excited, because that had happened the day before it aired. People, especially sound guys, were doing 36-hour shifts just to get the thing done. It was completely mad. Eventually we learnt how to do it quickly and it started to be possible—by the end of the third series we were getting six or seven minutes of topical stuff all written the day before, and it was enormous fun.It was very successful by that point as well.It was huge. The third show in the third series got 15 million viewers and it was the number two programme in the country that week. It had something for everyone. Some people would watch it for the football jokes, some would watch it for the politics. My dad, who was in the Navy, asked me to dinner with all these old admirals and captains, naval commanders, and they all watched it because they hated Michael Heseltine for all the cuts they were pushing through. There were stories about Prince Andrew and Fergie being big fans. Andrew used to have the show flown out by helicopter to his ship so he could watch it.One of my enduring memories was the Prince Andrew centrefold in the middle of the Spitting Image book, him lying naked with a string of sausages covering his modesty.We loved doing that book. How cheeky was that? After I quit in despair in ’86, because I was so tired and overworked, I went to Romania to do a programme, and the tourist bloke, this amazing charming cultured person, had somehow got hold of that book, and to him it was like the Bible, a revered document, because you couldn’t say any of these things in Romania. He almost knelt down and asked me to bless him. He said, “This is modern Jonathan Swift, it’s so brilliant.”I used to watch the show with my parents on Sunday night, even though I was too young to get a lot of the jokes. Were you proud of the fact that kids watched it, that it appealed to everyone?Yes. At the time, most of my friends in their early 30s thought I’d gone completely mad and that I’d made a terrible mistake. But the fortunes of all the programmes I’ve ever done were made by 15-year-olds really, because eventually they’d say to their mum and dad, “You’ve got to watch this.” It’s a sort of iron rule to me that the audience are much more intelligent than most people give them credit for, and if you tell something truthfully you can read it on all sorts of levels. My kids likeSouth ParkandFamily Guy, and you don’t need to know every reference to feel that it’s right. It has a feel about it. How important was it to you that you got messages across and maybe even changed people’s views?Roger always used to say, “Puppets don’t do fuck all.” We all felt really that we hadn’t achieved anything apart from make a programme that gave people a lot of laughs.Was there a sort of agenda?Well, no party political agenda, because the people on the show covered the whole spectrum. The puppet-makers were a really interesting bunch, a very high proportion of lapsed Catholics, a tremendous wild card as a group of people, because they’ve got this tremendous anger but also this sense of spirituality and meaning. And there were some really quite serious lefties in the puppet workshop who thought they were supping with the devil by even going into a television studio. And I’m sure there were probably some serious right-wingers among the puppeteers. I was a left-of-centre wet liberal. But what everybody agreed was there was an awful lot of shit happening, and most of us thought that a lot of the things the Thatcher government were doing were terrible, things like the poll tax and the miners’ strike were absolutely dreadful. And they seemed so sure of what they were doing, and the Labour Party under Kinnock was terribly ineffectual. We used to jokingly call ourselves Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, trying to make the case for the other side on a regular basis so that people would know what the issues were, because the papers were heavily biased towards the government. Mrs Thatcher was a very sensitive person actually, she wasn’t an iron lady at all, and Bernard Ingham, her press guy, would cut out only the nice things from the papers for her. So she would think she was doing great and the government was very popular, and then late at night on a Sunday, as is well known, she liked a couple of whiskeys with Dennis up in the flat, and they’d turn on the telly and seeSpitting Imageand she’d say, “What the hell’s this? This is completely out of kilter with the nation. Everybody knows we’re the most popular government since Churchill.” And she absolutely hated the programme, although I don’t suppose she ever watched more than about five minutes of it. And she was always under the impression that it was a BBC show, because it looked and felt like one, and it’s said to be one of the reasons why she was determined to bash the BBC.Did you ever meet any of the people you ripped into on the show?I bump into David Steel not infrequently, because he’s from the Borders and we usually go up there for Christmas. And I try to stay away because I think he’s the only person who’s gone on record as sayingSpitting Imageruined his life. It’s fascinating, people who were portrayed inSpitting Imageas weak or ineffectual or pathetic in some way are the ones who do all the complaining. The tough guys thought it was hilarious.Norman Tebbit, who we did as a bruiser in a leather jacket, loved the show. I interviewed him on the radio recently and we had a brilliant conversation. He said, “I really thought it was a funny show and I loved my puppet. I used to watch it every week.” David Owen was the same. He’s got lots of self-confidence, and thought it was absolutely hilarious with little David Steel in his pocket, because that was slightly what he was doing. Whereas David Steel would complain, “I’m 5'8"?! I’m half an inch taller than Neil Kinnock!” Heseltine came to the puppet auction we did a few years ago and he was fantastically funny about it. He always did like it. He used to try to buy his puppet under a pseudonym. I think the more senior members of the Royal Family and Mrs Thatcher didn’t like it.One of the great things you achieved with the show was that you made a lot of people, especially kids, aware of who politicians were. How aware were you at the time that you were informing people?The thing is, in the early days there was a very politicised backroom headed by Roger and Peter. They came from a political-satirical tradition and that’s what they wanted to do. And we decided very early on to build the Thatcher cabinet. One of the first ideas was to have a cabinet meeting every week, because there would be lots of people in it and we’d always be able to think of some way of dealing with the news.What are you most proud of with the show?Creatively, the General Election of 1987. Technically I was not the producer any more. Geoffrey Perkins was producing, I was the exec. We had this song at the end of the show, it went out literally half an hour after the polls had closed, so everyone was very raw, and the song was this parody of “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” fromCabaret. We had this young blond English boy singing it in a soprano voice, and we set it in this bierkeller with the newly elected Tories with Nazi armbands on. And I was sitting upstairs from the studio, in my executive capacity in my suit, and in the room with me is the chairman of the board of governors and the programme controller, all the bigwigs in grey suits. And when the programme finished there was this complete silence for what seemed like two years, and I looked at the floor and thought they were literally going to kill me. And they all got up and started cheering, it was extraordinary. Because some telly is so good it’s beyond politics, it doesn’t matter what side you’re on. It was so uncompromisingly rude, unbelievable. You just couldn’t do that now. Imagine what theMailwould say today if that went out. Well, they’d love it if it was anti-Labour.There’s been talk over the years of you trying to bring the show back.It comes up periodically. Roger and I did have a go a few years ago, and Talkback managed to make a mess of it and it didn’t get anywhere. And it still goes on, I’ve got a bloke in America at the moment who’s interested in it. You never know. The trouble is it’s going to cost probably £5 million to get it going, although we reckon after three years you’d start making money. But the main thing is, one doubts the editorial bravery of the people who run television now. It’s very hard to think these days of anyone who’s in television on the mission to explain, as John Birt used to call it, a mission to communicate. An awful lot of people who used to work in telly in the 80s believed in it as a thing worth doing for its own sake, making a really good programme. Nobody was doing it for the money, nobody. You couldn’t make money doing it. You had to do it for other reasons. And now an awful lot of people are in telly to have a good career. Rising up the greasy pole, making massive salaries.ROGER LAWRoger Law spent the 1960s and early 70s as an illustrator and cartoonist for newspapers and magazines all over the world, including theObserver,theSunday Times, Private EyeandNewsweek. In 1975 he teamed up with Peter Fluck to produce 3D caricatures, to great success, and the pair then co-createdSpitting Image, staying with the show for the entire 12-year run. Law now lives in Sydney and makes ceramics.Years before Spitting Image you did quite a bit of work with Peter Cook.Roger Law: Peter Cook came into my life because he was at Cambridge when I was at Cambridge School of Art. And I had a pretty girlfriend that he got hold of. Married her, actually. So I met him early on. And then when we all moved to London, I worked on the Observer where I did the drawings, and he used to write the captions at the last fucking minute. “I don’t want to see plays about sex and drugs and sodomy—I can get all that at home.” That was one of them.I heard something about you going to a talk by [Muppets creator] Jim Henson when you were starting out with Spitting Image.Peter Fluck and I went to the Edinburgh Festival, where he gave a talk. And we were so depressed because he held up Kermit, and said he made Kermit out of his mother’s coat. And the audience were absolutely rolling about on the floor because the puppet was reacting to what he said, very upset about being made out of his mum’s coat. And Henson said what you should and shouldn’t do with puppets. He said simple is good, and he said, “You cannot make a puppet of somebody, it will not work.”To some extent he was right, because one of the first puppets we made, before the television series, was Ronald Reagan. John Lloyd took the puppet to Griff Rhys Jones, who admittedly was pissed at the time—he was still drinking in those days—and we’d done this little pilot with an amateur camera, for our own benefit, and when Ronald Reagan came on Griff Rhys Jones nearly fell off his fucking chair, he couldn’t believe it. He thought itwasRonald Reagan, because he was so pissed. But the problem was that they didn’t sustain. None of the puppets, with the exception of the Queen, sustained for more than a minute—it would have to be cutaways all the time. You didn’t care about them the way you cared about Kermit. They were all loathsome. I hate puppets. I fucking hate them. But the problems we had were resolved when we made the programmes. With the first series, when we went to work in the morning on Canary Wharf, you could smell the fucking fear. You’d get inside and our eyelashes were stuck to our forehead, we were so petrified. And we fucked up in public for a whole series. And then suddenly it started to work. It started to work because the sketches were made shorter. We used one-liners. We never had anybody on screen for more than about 40 seconds. Tiny little bits of editing. Doing that kind of work to a newspaper deadline is fucking insane. And that’s what we had to do. I’ve worked on programmes where Lloydy was editing the second half as the first half went out. And you got adrenalin glands like pineapples.Yeah, it sounded like none of you got much sleep for the first two or three years.No, well, we took a lot of drugs. We fucking took everything going to keep going, you know. I think we became rather deranged. I know I did. The adrenalin rush you got… I mean I’m actually good on adrenalin.I wouldn’t have been a fucking journalist, I would never have been a fine artist come to think of it, because you get addicted to that kind of deadline bollocks. And you had it in spades onSpitting Image. I’m an alcoholic but I don’t drink any more, thank Christ, but I did then, and the show would finish on Sunday night and you’d drink an inordinate amount of alcohol, and then when you’d finished with Mr Alcohol you’d have a go at Mrs Marijuana. And you’d end up on the floor in a catatonic state, totally sober. Because the adrenalin was so high, you couldn’t actually bring yourself down. I tried to kill John Lloyd one night, because he never understood the craft of making the puppets, and it’s probably as well he didn’t because it didn’t hinder the ideas that he had. He had an idea with a writer and he’d ring you up and say, “Can I have 15 camels by tomorrow.” And you were pumping out 14 puppets a fucking week, with about 11 people in the workshop, if that. And I’d shout, “What the fuck are you going on about?!” And he’d say, “Come on, Rog, calm down, we’ve got two horses, can’t you put humps on those?” And then you’d settle for six camels. But he would never allow an idea to solidify in case he had a better one, which is no way to work when everything you see on camera is handmade. So I was pissed one night in Birmingham where we shot the programme, and I had to be physically restrained and have my hands prised from around his neck.

How important was it to you that you got messages across and maybe even changed people’s views?Roger always used to say, “Puppets don’t do fuck all.” We all felt really that we hadn’t achieved anything apart from make a programme that gave people a lot of laughs.Was there a sort of agenda?Well, no party political agenda, because the people on the show covered the whole spectrum. The puppet-makers were a really interesting bunch, a very high proportion of lapsed Catholics, a tremendous wild card as a group of people, because they’ve got this tremendous anger but also this sense of spirituality and meaning. And there were some really quite serious lefties in the puppet workshop who thought they were supping with the devil by even going into a television studio. And I’m sure there were probably some serious right-wingers among the puppeteers. I was a left-of-centre wet liberal. But what everybody agreed was there was an awful lot of shit happening, and most of us thought that a lot of the things the Thatcher government were doing were terrible, things like the poll tax and the miners’ strike were absolutely dreadful. And they seemed so sure of what they were doing, and the Labour Party under Kinnock was terribly ineffectual. We used to jokingly call ourselves Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, trying to make the case for the other side on a regular basis so that people would know what the issues were, because the papers were heavily biased towards the government. Mrs Thatcher was a very sensitive person actually, she wasn’t an iron lady at all, and Bernard Ingham, her press guy, would cut out only the nice things from the papers for her. So she would think she was doing great and the government was very popular, and then late at night on a Sunday, as is well known, she liked a couple of whiskeys with Dennis up in the flat, and they’d turn on the telly and seeSpitting Imageand she’d say, “What the hell’s this? This is completely out of kilter with the nation. Everybody knows we’re the most popular government since Churchill.” And she absolutely hated the programme, although I don’t suppose she ever watched more than about five minutes of it. And she was always under the impression that it was a BBC show, because it looked and felt like one, and it’s said to be one of the reasons why she was determined to bash the BBC.Did you ever meet any of the people you ripped into on the show?I bump into David Steel not infrequently, because he’s from the Borders and we usually go up there for Christmas. And I try to stay away because I think he’s the only person who’s gone on record as sayingSpitting Imageruined his life. It’s fascinating, people who were portrayed inSpitting Imageas weak or ineffectual or pathetic in some way are the ones who do all the complaining. The tough guys thought it was hilarious.Norman Tebbit, who we did as a bruiser in a leather jacket, loved the show. I interviewed him on the radio recently and we had a brilliant conversation. He said, “I really thought it was a funny show and I loved my puppet. I used to watch it every week.” David Owen was the same. He’s got lots of self-confidence, and thought it was absolutely hilarious with little David Steel in his pocket, because that was slightly what he was doing. Whereas David Steel would complain, “I’m 5'8"?! I’m half an inch taller than Neil Kinnock!” Heseltine came to the puppet auction we did a few years ago and he was fantastically funny about it. He always did like it. He used to try to buy his puppet under a pseudonym. I think the more senior members of the Royal Family and Mrs Thatcher didn’t like it.One of the great things you achieved with the show was that you made a lot of people, especially kids, aware of who politicians were. How aware were you at the time that you were informing people?The thing is, in the early days there was a very politicised backroom headed by Roger and Peter. They came from a political-satirical tradition and that’s what they wanted to do. And we decided very early on to build the Thatcher cabinet. One of the first ideas was to have a cabinet meeting every week, because there would be lots of people in it and we’d always be able to think of some way of dealing with the news.What are you most proud of with the show?Creatively, the General Election of 1987. Technically I was not the producer any more. Geoffrey Perkins was producing, I was the exec. We had this song at the end of the show, it went out literally half an hour after the polls had closed, so everyone was very raw, and the song was this parody of “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” fromCabaret. We had this young blond English boy singing it in a soprano voice, and we set it in this bierkeller with the newly elected Tories with Nazi armbands on. And I was sitting upstairs from the studio, in my executive capacity in my suit, and in the room with me is the chairman of the board of governors and the programme controller, all the bigwigs in grey suits. And when the programme finished there was this complete silence for what seemed like two years, and I looked at the floor and thought they were literally going to kill me. And they all got up and started cheering, it was extraordinary. Because some telly is so good it’s beyond politics, it doesn’t matter what side you’re on. It was so uncompromisingly rude, unbelievable. You just couldn’t do that now. Imagine what theMailwould say today if that went out. Well, they’d love it if it was anti-Labour.There’s been talk over the years of you trying to bring the show back.It comes up periodically. Roger and I did have a go a few years ago, and Talkback managed to make a mess of it and it didn’t get anywhere. And it still goes on, I’ve got a bloke in America at the moment who’s interested in it. You never know. The trouble is it’s going to cost probably £5 million to get it going, although we reckon after three years you’d start making money. But the main thing is, one doubts the editorial bravery of the people who run television now. It’s very hard to think these days of anyone who’s in television on the mission to explain, as John Birt used to call it, a mission to communicate. An awful lot of people who used to work in telly in the 80s believed in it as a thing worth doing for its own sake, making a really good programme. Nobody was doing it for the money, nobody. You couldn’t make money doing it. You had to do it for other reasons. And now an awful lot of people are in telly to have a good career. Rising up the greasy pole, making massive salaries.ROGER LAWRoger Law spent the 1960s and early 70s as an illustrator and cartoonist for newspapers and magazines all over the world, including theObserver,theSunday Times, Private EyeandNewsweek. In 1975 he teamed up with Peter Fluck to produce 3D caricatures, to great success, and the pair then co-createdSpitting Image, staying with the show for the entire 12-year run. Law now lives in Sydney and makes ceramics.Years before Spitting Image you did quite a bit of work with Peter Cook.Roger Law: Peter Cook came into my life because he was at Cambridge when I was at Cambridge School of Art. And I had a pretty girlfriend that he got hold of. Married her, actually. So I met him early on. And then when we all moved to London, I worked on the Observer where I did the drawings, and he used to write the captions at the last fucking minute. “I don’t want to see plays about sex and drugs and sodomy—I can get all that at home.” That was one of them.I heard something about you going to a talk by [Muppets creator] Jim Henson when you were starting out with Spitting Image.Peter Fluck and I went to the Edinburgh Festival, where he gave a talk. And we were so depressed because he held up Kermit, and said he made Kermit out of his mother’s coat. And the audience were absolutely rolling about on the floor because the puppet was reacting to what he said, very upset about being made out of his mum’s coat. And Henson said what you should and shouldn’t do with puppets. He said simple is good, and he said, “You cannot make a puppet of somebody, it will not work.”To some extent he was right, because one of the first puppets we made, before the television series, was Ronald Reagan. John Lloyd took the puppet to Griff Rhys Jones, who admittedly was pissed at the time—he was still drinking in those days—and we’d done this little pilot with an amateur camera, for our own benefit, and when Ronald Reagan came on Griff Rhys Jones nearly fell off his fucking chair, he couldn’t believe it. He thought itwasRonald Reagan, because he was so pissed. But the problem was that they didn’t sustain. None of the puppets, with the exception of the Queen, sustained for more than a minute—it would have to be cutaways all the time. You didn’t care about them the way you cared about Kermit. They were all loathsome. I hate puppets. I fucking hate them. But the problems we had were resolved when we made the programmes. With the first series, when we went to work in the morning on Canary Wharf, you could smell the fucking fear. You’d get inside and our eyelashes were stuck to our forehead, we were so petrified. And we fucked up in public for a whole series. And then suddenly it started to work. It started to work because the sketches were made shorter. We used one-liners. We never had anybody on screen for more than about 40 seconds. Tiny little bits of editing. Doing that kind of work to a newspaper deadline is fucking insane. And that’s what we had to do. I’ve worked on programmes where Lloydy was editing the second half as the first half went out. And you got adrenalin glands like pineapples.Yeah, it sounded like none of you got much sleep for the first two or three years.No, well, we took a lot of drugs. We fucking took everything going to keep going, you know. I think we became rather deranged. I know I did. The adrenalin rush you got… I mean I’m actually good on adrenalin.I wouldn’t have been a fucking journalist, I would never have been a fine artist come to think of it, because you get addicted to that kind of deadline bollocks. And you had it in spades onSpitting Image. I’m an alcoholic but I don’t drink any more, thank Christ, but I did then, and the show would finish on Sunday night and you’d drink an inordinate amount of alcohol, and then when you’d finished with Mr Alcohol you’d have a go at Mrs Marijuana. And you’d end up on the floor in a catatonic state, totally sober. Because the adrenalin was so high, you couldn’t actually bring yourself down. I tried to kill John Lloyd one night, because he never understood the craft of making the puppets, and it’s probably as well he didn’t because it didn’t hinder the ideas that he had. He had an idea with a writer and he’d ring you up and say, “Can I have 15 camels by tomorrow.” And you were pumping out 14 puppets a fucking week, with about 11 people in the workshop, if that. And I’d shout, “What the fuck are you going on about?!” And he’d say, “Come on, Rog, calm down, we’ve got two horses, can’t you put humps on those?” And then you’d settle for six camels. But he would never allow an idea to solidify in case he had a better one, which is no way to work when everything you see on camera is handmade. So I was pissed one night in Birmingham where we shot the programme, and I had to be physically restrained and have my hands prised from around his neck. He didn’t tell me about that.No, I’m sure he didn’t.He did tell me about the time you threw a chair at him when you were arguing about the miners’ strike.Yeah, I threw things around a lot. But that was good, that was healthy, because they used to do endless Arthur Scargill hair jokes, and the miners’ strike was actually rather about something. And you’d say, “Look, what they’re really going to do, John, they’re going to close the fucking mines.” It’s not really about Scargill and Thatcher, but they were the perfect Punch and Judy for the media, and the real things never got discussed. And John was endlessly curious, he’s a well-educated liberal, and a good fellow, and gradually through argument we found some other ways to satirise the miners’ strike and to make valid points. Because you don’t really want to be onside with Kelvin MacKenzie week in and week out, do you? So that was kind of a good process, I think. And I would ring up Birmingham at three in the morning, and the only fucker that answered the phone was John Lloyd. And I never fell out with John Lloyd seriously. I’m still frightfully fond of him actually.So from the beginning you were incredibly passionate about the show being seriously politically driven. Were there specific things you wanted to achieve in that respect?Yes. I was very angry and determined. It felt so right, I wanted to do this, and I understood Thatcher, I knew what the fucker was about. Before I didSpitting ImageI worked freelance on theSunday Timeswith [political editor] Hugo Young, and he said, “I want you to do a caricature of Thatcher. Have you read the Conservative Party Manifesto?” And I said, “For fuck’s sake, Hugo, that’s a call beyond duty. They all say they’re going to do something and never fucking well do.” And he said, “Read it. She’s going to do it. She’s going to do it.” And I read it, and I thought, “Fuck me. We’re going to be selling the family silver completely, and we’re becoming another state of America. We’re going to be a complete consumer society.” And Peter Fluck said to me, “Well, what she wants to do is make people insecure so they’ll fucking work. Throw back the lower-middle classes to where they came from, and create a sort of huge sub-class of people that we’re all going to be frightened of.” And we sort of knew that, because we were ten or 12 years older than Lloydy, so we were really keen thatSpitting Imageshould be that programme that showed you the other side of the coin. And it was perfect really because Thatcher was so black and white, and so were we. It’s difficult to do if you’ve got somebody you’re in empathy with, like Obama trying to do a job in a complete fucking mess. So, yeah, I would have killed my mother to do that show, actually.

He didn’t tell me about that.No, I’m sure he didn’t.He did tell me about the time you threw a chair at him when you were arguing about the miners’ strike.Yeah, I threw things around a lot. But that was good, that was healthy, because they used to do endless Arthur Scargill hair jokes, and the miners’ strike was actually rather about something. And you’d say, “Look, what they’re really going to do, John, they’re going to close the fucking mines.” It’s not really about Scargill and Thatcher, but they were the perfect Punch and Judy for the media, and the real things never got discussed. And John was endlessly curious, he’s a well-educated liberal, and a good fellow, and gradually through argument we found some other ways to satirise the miners’ strike and to make valid points. Because you don’t really want to be onside with Kelvin MacKenzie week in and week out, do you? So that was kind of a good process, I think. And I would ring up Birmingham at three in the morning, and the only fucker that answered the phone was John Lloyd. And I never fell out with John Lloyd seriously. I’m still frightfully fond of him actually.So from the beginning you were incredibly passionate about the show being seriously politically driven. Were there specific things you wanted to achieve in that respect?Yes. I was very angry and determined. It felt so right, I wanted to do this, and I understood Thatcher, I knew what the fucker was about. Before I didSpitting ImageI worked freelance on theSunday Timeswith [political editor] Hugo Young, and he said, “I want you to do a caricature of Thatcher. Have you read the Conservative Party Manifesto?” And I said, “For fuck’s sake, Hugo, that’s a call beyond duty. They all say they’re going to do something and never fucking well do.” And he said, “Read it. She’s going to do it. She’s going to do it.” And I read it, and I thought, “Fuck me. We’re going to be selling the family silver completely, and we’re becoming another state of America. We’re going to be a complete consumer society.” And Peter Fluck said to me, “Well, what she wants to do is make people insecure so they’ll fucking work. Throw back the lower-middle classes to where they came from, and create a sort of huge sub-class of people that we’re all going to be frightened of.” And we sort of knew that, because we were ten or 12 years older than Lloydy, so we were really keen thatSpitting Imageshould be that programme that showed you the other side of the coin. And it was perfect really because Thatcher was so black and white, and so were we. It’s difficult to do if you’ve got somebody you’re in empathy with, like Obama trying to do a job in a complete fucking mess. So, yeah, I would have killed my mother to do that show, actually. And how much of that was successful, from your point of view?Well, when it first started we couldn’t fucking believe how awful it was. We thought it was going to be political for the whole 28 minutes, and of course it fucking wasn’t, there was lightweight stuff. We were used to working for theObserver,theSunday Times, Newsweek—fairly serious journalism and fairly intelligent commentary. So we weren’t used to that kind of populist attraction thatSpitting Imagehad. Once we realised that we had our audience—our old audience—back by the third series, theObserverandSunday Times-reading, lager-drinking, new-car-buying wankers, we had them back, but we also had a huge section from Kelvin MacKenzie. And I saw Peter Cook about four years into the show down at Canary Wharf. He was in some programme or film and he was in some caravan—you know, they give the star a caravan—and I spent some time in there talking to him and I said, “Come on then, how do you rateSpitting Image?” And he said, “Oh I love it, I watch it.” And I said, “What do you mean, you watch it for the politics?” And he said, “No, no, fuck that. My interest inSpitting Imageis the stuff on football.”Right. It was great how even kids knew who was in the cabinet and shadow cabinet because of Spitting Image.Yeah. There were great moments. I remember one election time, I was actually at home for breakfast, which was brilliant, and I got the papers and on the front of theSunday Timesthere were pre-election summings up. The election was on the following Monday or Tuesday, and my wife said, “Good heavens, all of the photos of the politicians are your puppets.” They’d used the puppets instead of photos of the politicians. I hadn’t even fucking noticed. That’s how real they were to me. And I think the same was true for other people, they really got confused between Norman Tebbit the thug and Norman Tebbit the politician-thug. Lloydy used to sometimes go to parties where some of the puppets’ counterparts appeared. Leon Brittan always had boils that were full of pus that used to come out when he was on screen. And his wife went up to Lloydy and said, “Not enough spots, not enough spots.” But I didn’t mix with those fucking people. And I had no wish to.OK, thanks. If we send a photographer over to you, do you have any puppets with you?No, I don’t fucking want those puppets near me.HARRY ENFIELDHarry Enfield became famous in front of the cameras at the same time as providing voices forSpitting Image. With co-creator Paul Whitehouse (who went on to do theFast Show), he brought Greek kebab-king Stavros and obnoxious oik Loadsamoney to Channel 4’sSaturday Livebefore getting his own series on the BBC. A slew of shows have followed, as well as a film (Kevin & Perry Go Large), and a recurring role inSkins. The third series of his and Whitehouse’sHarry and Paulhas just finished on BBC 2, and the pair plan to tour next year.I spoke to John Lloyd and Roger Law, who both seemed to suffer physically from working so hard on Spitting Image. I’m assuming you worked more civilised hours and probably didn’t have that.Harry Enfield:No, I didn’t at all. I would do one day a week.It sounds like they were doing 18-hour days.Yeah, they were, and they were drinking heavily, which didn’t help. I remember the first time I met John, before I got the job. I met him at lunch about something else, about this Norbert Smith [TV mockumentary] thing I did a few years later, because I wanted him to produce that, and he said, “I can’t, but I’m doing this programme calledSpitting Image. Do you want to do it?” That’s how I got involved.What were you doing at that point?I was nothing, I was on the [stand-up] circuit just pissing about with my mate Brian.So this was your first gig.My first professional gig, yeah. I remember that first lunch we had. It wasn’t even a lunch. I went for a meeting with him and then we went to a pub in Soho and he drank four pints. And I thought, “Fuck me, we’ve only gone to a meeting and he’s had four pints.” And I think I had one, thinking I better have something. But it took me the whole lunch to get through the one. And he had four, and he was still fine! It would have been 1985, I think, so I would have been 24 and he would have been 34. And he was running this show, and this was lunchtime. But they were hard-drinking people. It’s not like that any more. People working at the BBC drank masses in the pub every lunchtime.So what was it like for all you voice people together in one room doing the work?Well, it wasn’t a room. If you’re accurate about it, it was a massive studio at Central in Birmingham. It was all unionised so we had to be there 9 o’clock on the dot, because that’s when the unions started work. And they had to have a half-an-hour tea break at 11. So the big rule was you couldn’t be late, because it was so expensive. It was a massive studio—thinkX Factor—this big studio with one microphone in it, and five people doing voices round this one microphone, and about ten technical people, because of the unions, all fluttering around doing fuck all. It was very bizarre. And we did it on the set of [TV soap]Crossroads. During the week it wasCrossroads, and on the weekend they’d put a microphone in there for us. So you’d be in the bedroom or the living room of some character’s house, and they’d have photos of them in their house, like their wedding day photos. And Enn Reitel, who used to do some of the voices, he used to put little moustaches on them, and we’d see if we could spot them on telly the next week. And we had the same floor manager, this big fat man from Birmingham, properly massive, who thought nothing was funny, and he’d stand there with this horrible withering look on his face, like, “This isn’t funny.On the Buseswas funny. This isn’t funny.” Ugh. So we had to deal with him snarling at us, then he’d walk out at 11 o’clock for his break and would say, “Right—stop. All right everyone, come on—tea break.” And we’d all have to stop in the middle of a sketch.Who else was doing voices with you?Chris Barrie was the king, I would say. He was the best mimic I’d ever seen, he was really, really brilliant. And he was the only proper impressionist. And there was Steve Nallon, who did Thatcher. Early on they had some puppeteers doing some voices as well, and when I joined we started supplanting the puppeteers a bit. And it was me, Jon Glover, who played Mr Cholmondley-Warner in my series later on, and Enn Reitel, who was the other brilliant impressionist, absolutely brilliant. And then John Sessions came in, and Jan Ravens, and Kate Robbins. So John Lloyd would ask who could do a certain person, and we’d all have a go auditioning.Was it competitive?No, but it was slightly embarrassing. It’s one of the reasons I can never watchMock the Week, because there’s that bit at the end where they all try to outdo each other, each one waiting and then going up to the mic to do a joke about a particular topic. It’s so competitive and it just reminds me of that time where we all used to have to do our Ken Livingstone or whoever it was. It was a bit embarrassing.I read somewhere that Steve Nallon said although you weren’t the best impressionist, you were the best caricaturist, and you physically threw yourself into your performances.Well… hmm. I think he’s being nice there. Steve started the year I left. I just winged it. I knew I wasn’t a very good impressionist so I thought I’d just do it bigger. And it sort of works with the characters because they were rubber.

And how much of that was successful, from your point of view?Well, when it first started we couldn’t fucking believe how awful it was. We thought it was going to be political for the whole 28 minutes, and of course it fucking wasn’t, there was lightweight stuff. We were used to working for theObserver,theSunday Times, Newsweek—fairly serious journalism and fairly intelligent commentary. So we weren’t used to that kind of populist attraction thatSpitting Imagehad. Once we realised that we had our audience—our old audience—back by the third series, theObserverandSunday Times-reading, lager-drinking, new-car-buying wankers, we had them back, but we also had a huge section from Kelvin MacKenzie. And I saw Peter Cook about four years into the show down at Canary Wharf. He was in some programme or film and he was in some caravan—you know, they give the star a caravan—and I spent some time in there talking to him and I said, “Come on then, how do you rateSpitting Image?” And he said, “Oh I love it, I watch it.” And I said, “What do you mean, you watch it for the politics?” And he said, “No, no, fuck that. My interest inSpitting Imageis the stuff on football.”Right. It was great how even kids knew who was in the cabinet and shadow cabinet because of Spitting Image.Yeah. There were great moments. I remember one election time, I was actually at home for breakfast, which was brilliant, and I got the papers and on the front of theSunday Timesthere were pre-election summings up. The election was on the following Monday or Tuesday, and my wife said, “Good heavens, all of the photos of the politicians are your puppets.” They’d used the puppets instead of photos of the politicians. I hadn’t even fucking noticed. That’s how real they were to me. And I think the same was true for other people, they really got confused between Norman Tebbit the thug and Norman Tebbit the politician-thug. Lloydy used to sometimes go to parties where some of the puppets’ counterparts appeared. Leon Brittan always had boils that were full of pus that used to come out when he was on screen. And his wife went up to Lloydy and said, “Not enough spots, not enough spots.” But I didn’t mix with those fucking people. And I had no wish to.OK, thanks. If we send a photographer over to you, do you have any puppets with you?No, I don’t fucking want those puppets near me.HARRY ENFIELDHarry Enfield became famous in front of the cameras at the same time as providing voices forSpitting Image. With co-creator Paul Whitehouse (who went on to do theFast Show), he brought Greek kebab-king Stavros and obnoxious oik Loadsamoney to Channel 4’sSaturday Livebefore getting his own series on the BBC. A slew of shows have followed, as well as a film (Kevin & Perry Go Large), and a recurring role inSkins. The third series of his and Whitehouse’sHarry and Paulhas just finished on BBC 2, and the pair plan to tour next year.I spoke to John Lloyd and Roger Law, who both seemed to suffer physically from working so hard on Spitting Image. I’m assuming you worked more civilised hours and probably didn’t have that.Harry Enfield:No, I didn’t at all. I would do one day a week.It sounds like they were doing 18-hour days.Yeah, they were, and they were drinking heavily, which didn’t help. I remember the first time I met John, before I got the job. I met him at lunch about something else, about this Norbert Smith [TV mockumentary] thing I did a few years later, because I wanted him to produce that, and he said, “I can’t, but I’m doing this programme calledSpitting Image. Do you want to do it?” That’s how I got involved.What were you doing at that point?I was nothing, I was on the [stand-up] circuit just pissing about with my mate Brian.So this was your first gig.My first professional gig, yeah. I remember that first lunch we had. It wasn’t even a lunch. I went for a meeting with him and then we went to a pub in Soho and he drank four pints. And I thought, “Fuck me, we’ve only gone to a meeting and he’s had four pints.” And I think I had one, thinking I better have something. But it took me the whole lunch to get through the one. And he had four, and he was still fine! It would have been 1985, I think, so I would have been 24 and he would have been 34. And he was running this show, and this was lunchtime. But they were hard-drinking people. It’s not like that any more. People working at the BBC drank masses in the pub every lunchtime.So what was it like for all you voice people together in one room doing the work?Well, it wasn’t a room. If you’re accurate about it, it was a massive studio at Central in Birmingham. It was all unionised so we had to be there 9 o’clock on the dot, because that’s when the unions started work. And they had to have a half-an-hour tea break at 11. So the big rule was you couldn’t be late, because it was so expensive. It was a massive studio—thinkX Factor—this big studio with one microphone in it, and five people doing voices round this one microphone, and about ten technical people, because of the unions, all fluttering around doing fuck all. It was very bizarre. And we did it on the set of [TV soap]Crossroads. During the week it wasCrossroads, and on the weekend they’d put a microphone in there for us. So you’d be in the bedroom or the living room of some character’s house, and they’d have photos of them in their house, like their wedding day photos. And Enn Reitel, who used to do some of the voices, he used to put little moustaches on them, and we’d see if we could spot them on telly the next week. And we had the same floor manager, this big fat man from Birmingham, properly massive, who thought nothing was funny, and he’d stand there with this horrible withering look on his face, like, “This isn’t funny.On the Buseswas funny. This isn’t funny.” Ugh. So we had to deal with him snarling at us, then he’d walk out at 11 o’clock for his break and would say, “Right—stop. All right everyone, come on—tea break.” And we’d all have to stop in the middle of a sketch.Who else was doing voices with you?Chris Barrie was the king, I would say. He was the best mimic I’d ever seen, he was really, really brilliant. And he was the only proper impressionist. And there was Steve Nallon, who did Thatcher. Early on they had some puppeteers doing some voices as well, and when I joined we started supplanting the puppeteers a bit. And it was me, Jon Glover, who played Mr Cholmondley-Warner in my series later on, and Enn Reitel, who was the other brilliant impressionist, absolutely brilliant. And then John Sessions came in, and Jan Ravens, and Kate Robbins. So John Lloyd would ask who could do a certain person, and we’d all have a go auditioning.Was it competitive?No, but it was slightly embarrassing. It’s one of the reasons I can never watchMock the Week, because there’s that bit at the end where they all try to outdo each other, each one waiting and then going up to the mic to do a joke about a particular topic. It’s so competitive and it just reminds me of that time where we all used to have to do our Ken Livingstone or whoever it was. It was a bit embarrassing.I read somewhere that Steve Nallon said although you weren’t the best impressionist, you were the best caricaturist, and you physically threw yourself into your performances.Well… hmm. I think he’s being nice there. Steve started the year I left. I just winged it. I knew I wasn’t a very good impressionist so I thought I’d just do it bigger. And it sort of works with the characters because they were rubber. Were there some you enjoyed doing more than others?Yeah, I loved doing David Steel, because I was doing it with Chris Barrie, who was doing David Owen, and it was like a little double act. And Ian Hislop and Nick Newman really liked writing for them, and once we’d established how it worked, vocally, they loved it and could hear our voices, so it was always a good sketch to do. And Geoffrey Howe, no one could do him, so I just sort of mumbled, and it seemed to work. And then suddenly you’d see these sketches come in from people who’d never written for Geoffrey Howe before, because they’d heard me do it, and that was fun. By 1990 we’d come down to London and were doing it in a smart voiceover studio in Soho, the whole union thing had relaxed, and it was just completely different. That was after I’d done Loadsamoney, and it was on Saturdays, and it wasn’t very well paid for me then, so I stopped doing it.Did you ever meet David Steel?Yeah, I had him on my show, he was really sweet. The first series I did, I was doing a Conservative person, and there was a Labour bloke, and we needed a Liberal Democrat so we thought we’d ask David Steel and he said yes. And he had to come to the BBC studios and do it on the night Thatcher resigned. He missed her resignation speech. Amazing. He must so regret that. But he was terribly nice.Even though he credits Spitting Image with ruining his reputation.Yeah, but it’s totally untrue, obviously. We didn’t have any power at all. It’s very flattering to me. It’s very nice of him to say that, in a way, because it credits you with far more power than you had, because we didn’t have any power. We solidly attacked the Conservative government through three elections they won.Apparently Leon Brittan was quite upset with you as well.Yeah, yeah! I met him. He was at William Hague’s house when I was there, and I said, “You’re responsible for my career. I only got my job onSpitting Imagebecause I could do you, and no one else could do you. And my whole career spun from doing that.” And he’d been really jolly, he was a bit like Simon Callow inA Room With a View, this big jolly vicar, and then he just looked a bit sad, and he said, “We haven’t all got such thick skins as you think.” And I thought, that’s really funny! He wasn’t telling me off or anything, but he obviously found it quite upsetting. I thought that was so weird: he would stand in the House of Commons being slagged off by 300 people every day for five years—you know, he was the Home Secretary—and he finds some crap impression of him hurtful. I don’t know if he really did, but that’s certainly what he said.As a voice artist, did you have a political drive in terms of what you were doing?Yes, I think I did at the time. And I definitely didn’t like the political feeling of the programme. I definitely found it very wishy-washy and middle of the road, and thought it should be attacking everyone right-wing far more. But it was swings and roundabouts. John was very funny and good at the comedy, but he definitely wasn’t a leftie, and he didn’t even understand the concept of being a leftie. And I was a leftie at the time. And still am, in a very right-wing way.Did working on the show influence you as a comedian?Yes, definitely. All John Lloyd, the way he worked. I was working with the best producer of that generation. He was very, very strict on scripts and why something wasn’t working. He wore his heart on his sleeve, and would pace around the place grimacing, looking utterly fed-up, and he’d give you these withering looks if you couldn’t make a character work, and then he’d work out it was something to do with the script, or whatever, and then he’d shriek with laughter. It was this roller coaster, seeing this bloke’s emotional journey all day over a bunch of scripts. It was very interesting and powerful to work with. And I found it terrifying in a way, but definitely a good thing, to see how strict and passionate you should be when you’re making something.Spitting Image Series 1-8are available on DVD through Network.

Were there some you enjoyed doing more than others?Yeah, I loved doing David Steel, because I was doing it with Chris Barrie, who was doing David Owen, and it was like a little double act. And Ian Hislop and Nick Newman really liked writing for them, and once we’d established how it worked, vocally, they loved it and could hear our voices, so it was always a good sketch to do. And Geoffrey Howe, no one could do him, so I just sort of mumbled, and it seemed to work. And then suddenly you’d see these sketches come in from people who’d never written for Geoffrey Howe before, because they’d heard me do it, and that was fun. By 1990 we’d come down to London and were doing it in a smart voiceover studio in Soho, the whole union thing had relaxed, and it was just completely different. That was after I’d done Loadsamoney, and it was on Saturdays, and it wasn’t very well paid for me then, so I stopped doing it.Did you ever meet David Steel?Yeah, I had him on my show, he was really sweet. The first series I did, I was doing a Conservative person, and there was a Labour bloke, and we needed a Liberal Democrat so we thought we’d ask David Steel and he said yes. And he had to come to the BBC studios and do it on the night Thatcher resigned. He missed her resignation speech. Amazing. He must so regret that. But he was terribly nice.Even though he credits Spitting Image with ruining his reputation.Yeah, but it’s totally untrue, obviously. We didn’t have any power at all. It’s very flattering to me. It’s very nice of him to say that, in a way, because it credits you with far more power than you had, because we didn’t have any power. We solidly attacked the Conservative government through three elections they won.Apparently Leon Brittan was quite upset with you as well.Yeah, yeah! I met him. He was at William Hague’s house when I was there, and I said, “You’re responsible for my career. I only got my job onSpitting Imagebecause I could do you, and no one else could do you. And my whole career spun from doing that.” And he’d been really jolly, he was a bit like Simon Callow inA Room With a View, this big jolly vicar, and then he just looked a bit sad, and he said, “We haven’t all got such thick skins as you think.” And I thought, that’s really funny! He wasn’t telling me off or anything, but he obviously found it quite upsetting. I thought that was so weird: he would stand in the House of Commons being slagged off by 300 people every day for five years—you know, he was the Home Secretary—and he finds some crap impression of him hurtful. I don’t know if he really did, but that’s certainly what he said.As a voice artist, did you have a political drive in terms of what you were doing?Yes, I think I did at the time. And I definitely didn’t like the political feeling of the programme. I definitely found it very wishy-washy and middle of the road, and thought it should be attacking everyone right-wing far more. But it was swings and roundabouts. John was very funny and good at the comedy, but he definitely wasn’t a leftie, and he didn’t even understand the concept of being a leftie. And I was a leftie at the time. And still am, in a very right-wing way.Did working on the show influence you as a comedian?Yes, definitely. All John Lloyd, the way he worked. I was working with the best producer of that generation. He was very, very strict on scripts and why something wasn’t working. He wore his heart on his sleeve, and would pace around the place grimacing, looking utterly fed-up, and he’d give you these withering looks if you couldn’t make a character work, and then he’d work out it was something to do with the script, or whatever, and then he’d shriek with laughter. It was this roller coaster, seeing this bloke’s emotional journey all day over a bunch of scripts. It was very interesting and powerful to work with. And I found it terrifying in a way, but definitely a good thing, to see how strict and passionate you should be when you’re making something.Spitting Image Series 1-8are available on DVD through Network.