New York Police officers stand guard at the entrance of Trump Tower, in New York on November 17, 2016. EDUARDO MUNOZ ALVAREZ/AFP/Getty Images

In the early hours of an icy morning in 1993, Robert Beck and his college friends left a Halloween party in Pittsburgh. The 23-year-old had borrowed his parents' car for the occasion, and the vehicle swerved as he moved to pull out of a parking lot. That's around the time local cop Anthony Williams blocked Beck's path with his cruiser, apparently determined to question the rehabilitation counselor about drunk driving. Beck would later testify in court that he was beaten and pistol-whipped in the course of being arrested, and that the police officer was never disciplined despite a history of excessive force.Beck's was just one of many Pittsburgh-area police brutality cases to produce litigation and draw media scrutiny in the 1990s. At the time, however, there was no formal mechanism by which the federal government could rein in rogue cops. But in 1994, Congress passed a bill that allowed the feds—and specifically the Department of Justice—to intervene when they suspected systemic civil rights violations. An ensuing probe of the Pittsburgh PD produced the first-ever settlement between the DOJ and local law enforcement.These court-ordered deals, known as consent decrees, have served as a cornerstone of police reform in America ever since. In the past few years alone, cities with notorious cops like Ferguson, Missouri, and Cleveland, Ohio, have been slapped with decrees, and while federal intervention is hardly a panacea for sloppy, prejudiced, or straight-up brutal policing, there is some evidence it can force meaningful changes. Now experts and advocates fear that under a Trump administration, America's most promising method of taming police officers could essentially evaporate. That, in turn, might lead to an uptick in use of deadly force in a country already reeling from a deluge of police killings and angry protests."These issues will be front and center over the next few years and you will see an increase in police misconduct," says Tim O'Brien, an attorney formerly with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Pittsburgh. "That much I can pretty much guarantee."Prior to the 90s, someone who was manhandled or mistreated by the cops could only sue for damages. But as the Washington Post reports, in the wake of grisly national spectacles like the infamous 1991 video showing Los Angeles Police Department officers beating motorist Rodney King, Congress realized the need for a way to hold entire departments accountable for systemic wrongdoing. The monitor needed to be independent, since officers were often reluctant to discipline each other thanks to a code of silence—sometimes called the the "Blue Wall"—and resistant police unions. Once the 1994 law was passed, if the feds found evidence of wrongdoing, the options for a town or city were to either quickly change course, strike a deal on a consent decree, or get sued into oblivion.The DOJ's Civil Rights Division has launched almost 70 such investigations, with the Obama administration pursuing more of them than its predecessors. Under Attorney Generals Eric Holder and Loretta Lynch, the DOJ entered into 11 consent decrees with police departments, some of them following high-profile shootings that helped catalyze the Black Lives Matter movement. And as part of a broader criminal justice drive, President Obama convened a Task Force on 21st Century Policing that produced a sort of guidebook on how to improve community-police relations.The question is whether this kind of federal attention will vanish come 2017."It's widely understood that the activities of the Civil Rights Division vary wildly depending on who the president and AG are," says Ben Trachtenberg, a law professor at the University of Missouri. He adds that under a Trump administration, it's unlikely the recent pattern of more rigorous scrutiny will continue. After all, the president-elect made a practice of dramatically ejecting BLM matter protestors from his campaign events, and centered his acceptance speech as the Republican National Convention on maintaining "law and order." That strong pro-police stance will most certainly carry over to his pick for attorney general, who is expected to be announced any day now.Whether the next AG former NYC mayor Rudy Giuliani—a champion of stop-and-frisk—or some other Trump cheerleader, the appointment is unlikely to be a boon for civil rights investigations in America.

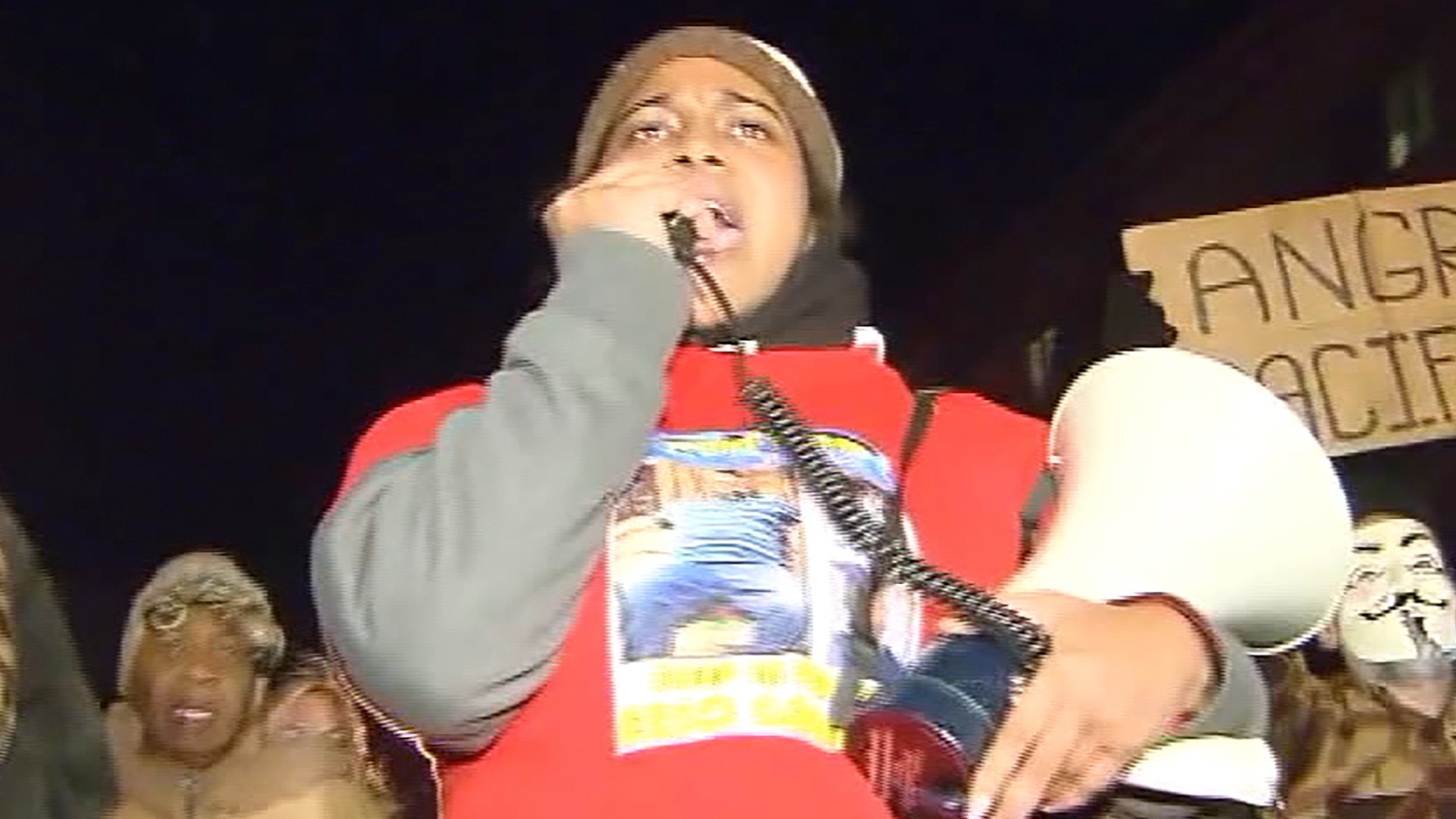

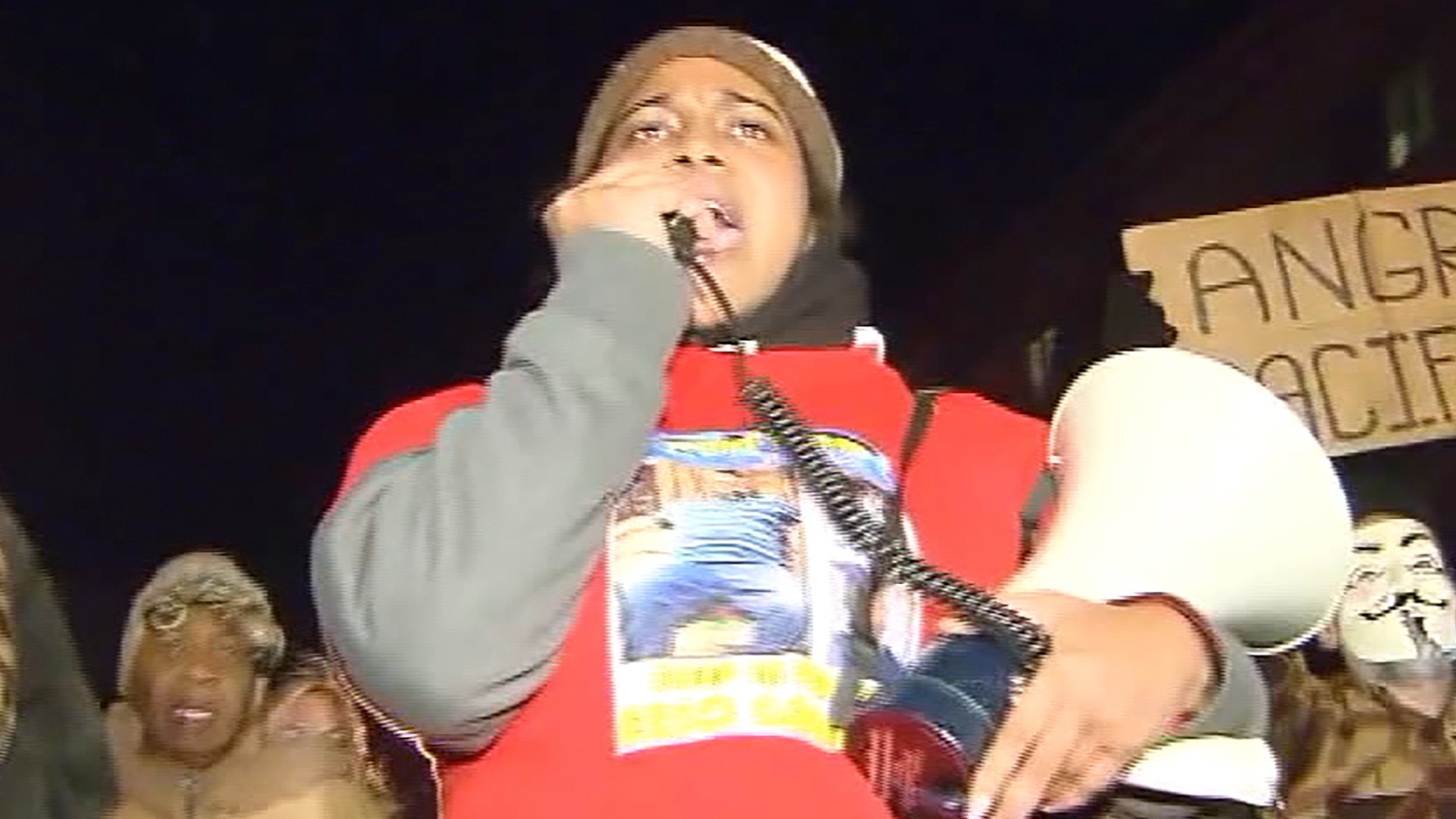

Watch Erica Garner, daughter of the man killed by the NYPD on Staten Island in 2014, talk about her vision for police reform in America.

The good news for reformers is that once a consent decree is imposed, enforcement becomes the responsibility of a federal judge, who has the ability to hold officials in contempt if they don't follow the new rules. That will make it tough for Trump's new AG to undo ongoing police-reform efforts in cities like Ferguson. But Trachtenberg says open investigations that haven't yet reached the consent decree stage could theoretically be called off by the new head of the DOJ depending on their political bent.Trachtenberg adds that there are still avenues for change under a more uniformly pro-cop Justice Department, citing Mayor Bill de Blasio's piecemeal criminal justice reforms in New York City. But while politicians will maintain the ability to intervene on a local level, Jeffrey Fagan, the Columbia University law professor who co-authored a key expert report on stop and frisk in NYC, says Trump would have the ability to massively reduce police oversight by sharply defunding the Civil Rights Division at the DOJ."Any of the mentioned attorney general candidates would be hostile to police reform, and probably would kill the data collection efforts currently being designed," Fagan says. "They would set the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing on fire."Follow Allie Conti on Twitter.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Watch Erica Garner, daughter of the man killed by the NYPD on Staten Island in 2014, talk about her vision for police reform in America.

The good news for reformers is that once a consent decree is imposed, enforcement becomes the responsibility of a federal judge, who has the ability to hold officials in contempt if they don't follow the new rules. That will make it tough for Trump's new AG to undo ongoing police-reform efforts in cities like Ferguson. But Trachtenberg says open investigations that haven't yet reached the consent decree stage could theoretically be called off by the new head of the DOJ depending on their political bent.Trachtenberg adds that there are still avenues for change under a more uniformly pro-cop Justice Department, citing Mayor Bill de Blasio's piecemeal criminal justice reforms in New York City. But while politicians will maintain the ability to intervene on a local level, Jeffrey Fagan, the Columbia University law professor who co-authored a key expert report on stop and frisk in NYC, says Trump would have the ability to massively reduce police oversight by sharply defunding the Civil Rights Division at the DOJ."Any of the mentioned attorney general candidates would be hostile to police reform, and probably would kill the data collection efforts currently being designed," Fagan says. "They would set the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing on fire."Follow Allie Conti on Twitter.