Advertisement

Patrick Keiller: The three Robinson films [London, Robinson in Space, and Robinson in Ruins] are all attempts to address a "problem" by exploring a landscape with a cine-camera. In Robinson in Space, for example, an initial assumption that the UK’s social and economic ills are the result of it being a backward, flawed capitalism gradually gave way to the realization that, on the contrary, these problems are the result of the economy’s successful operation in the interests of the people who own it.

Advertisement

The Elephant is unusual in that it’s the end of an underground line but very near the center of the city, so there are always a lot of people at the bus stops, as you see in the film. It was the hub of the South London tram network. I was intrigued that the shopping center had never been very successful commercially.The pictures of the Elephant in London are mostly of the shopping center and some nearby 1960s single-story GLC prefabs that were about to be cleared away when we were photographing the film. An elderly couple had lived in one of them since 1965. As the film relates, "After 27 years in the house, where they had brought up all their children, they were reluctant to leave and had been offered nothing with comparable amenities; but as their neighbors disappeared one by one, the house was increasingly vulnerable and they no longer felt able to leave it for more than a couple of days."

Advertisement

I'm interested in models of housing that aren't exclusively residential and aren't based on the individual nuclear family. In the UK now and recently, that seems to mean living on your own—a lot of present-day housing demand is the result of couples splitting up. Communications technology probably makes living on your own less isolating than it might otherwise be, but it doesn't strike me as very attractive. Living as an independent member of a larger unit might be more engaging.

Advertisement

We’re living with an economic reality in which profits aren’t so much derived from creating wealth as by transferring it, often from the poor to the rich. In former times, wealth creation meant investing in production and infrastructure, but now we encounter these extraordinary examples of asset-price inflation. In London, that means placing capital in property, much of it residential. As you say, many of these owners find it easier to leave their buildings empty, especially if they’re based elsewhere, which they often are. I wouldn’t have thought it was very difficult to legislate against this kind of thing, but any such discussion seems to be off the political agenda, just as hardly anyone ever mentions rent control.

Advertisement

There’s a lot of cultural and critical attention devoted to the experience of mobility and displacement. But often the emphasis is on their negative aspects, and we still tend to fall back on assumptions about dwelling derived from a more settled, agricultural past. This kind of place-centred dwelling is very problematic, as we see all the time in the Middle East, the UK, and elsewhere. But that doesn’t mean that we can dispense with claims on territory, or with territory’s claims on us. That’s what tax avoiders do—the super-rich think they’re above the level of the nation-state. But equally, the idea of ancestral rights to settlement is just not practical. In the UK, hardly anyone isn’t "displaced" to some extent.In England, this accompanied private ownership of land and property. Before land enclosure, a process that dates from the 16th century or earlier, ordinary people had rights to land. Land was enclosed by a rising class of gentry, often unlawfully, in a process that very much resembles what is happening today with, for example, the privatization of Royal Mail. I think it’s time to begin a discussion of how to socialize the value of land, and to return formerly public assets to public ownership.

Advertisement

It’s interesting to see how successfully these big infrastructure projects—Crossrail, the Jubilee Line extension and the Olympics—can be accomplished when there’s a political will behind them. Just think what could be achieved with energy efficiency, or "rebalancing" the economy away from financial services towards manufacturing, if there was a similar commitment. Crossrail is driven partly by the requirement to improve access to Canary Wharf from the west, especially from Heathrow, for those in the financial sector, hence the political will. I’m looking forward to its completion rather as I used to look forward to a new toy. I don’t really know what its wider impact will be, apart from increasing house prices even more and making it possible for more people to commute from far away, which seems a terrible waste of time.

Judging by his recent pronouncements, Johnson seems to understand success only in terms of money. He seemed to be suggesting that there’s a finite amount of wealth and a struggle in which the poor are those who lose out because they’re less "intelligent." He represents the interests of those who profit from dealing in assets, rather than investing in production. Larry Elliott pointed out recently that the UK hasn’t produced a single world-class manufacturing firm from scratch since World War Two. Johnson is a typical member of the elite responsible for this failure.

Advertisement

The economy is in even worse shape now than it was under the last Tory government, and that’s reflected in aspects of the landscape, especially the urban landscape. After 1997, Labour continued Thatcher’s strategy of "undisclosed" redistribution, in which the private sector was allowed to prosper in the southeast while the government supported public-sector jobs in other parts of the country, notably the northeast and Wales. The current government is abandoning that without replacing it with anything else, with disastrous consequences.A lot of your work deals in ruins, but is there anywhere in the UK that you feel still has a great future?

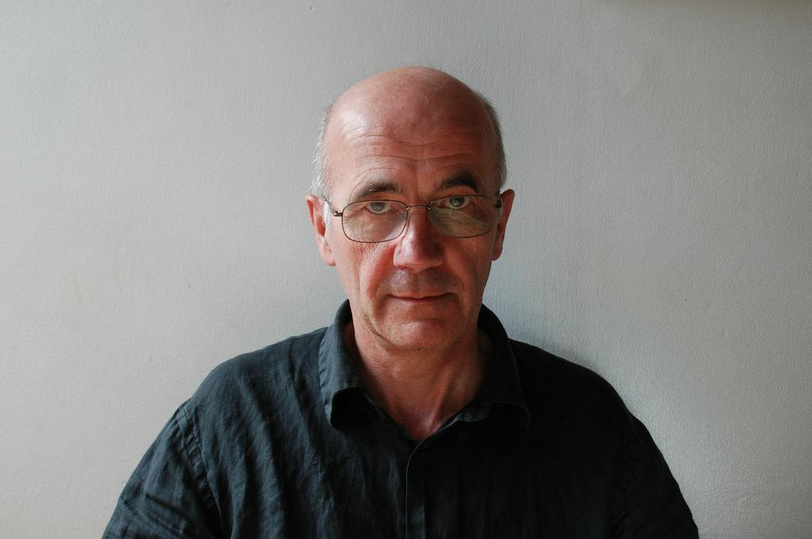

I find Sheffield a very encouraging city, although I wish they weren’t going to knock down Castle Market—it’s one of my favorite buildings. Halifax, Newcastle, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, too. I’m attracted to cities in which there are a lot of hills.Patrick Keiller’s films London, Robinson in Space and Robinson in Ruins are available on DVD and Blu-ray, released by BFI Video. His collection of essays The View from the Train is published by Verso – pick it up from Amazon here.Follow Nathalie on Twitter: @NROlah