The deadliest conflict since World War II – The "Second" Congo War – has kicked off again. Uganda and Rwanda are allegedly financing the M23 rebel movement, which is made up of deserters from Congo’s national army who mutinied in April 2012, after complaining that they weren't being paid.When the war began in August 1998, I was in Kinshasa, the Congolese capital. Laurent Kabila, a former freedom fighter in the bush and now president, had turned Congo into a tropical version of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, developing a personality cult, which dwarfed that of previous president Mobutu.

Advertisement

We land in Kinshasa early in the morning and walk along the airstrip to the arrivals lounge. The air is muggy and the sky grey. I am one of the few Westerners on the flight from London, and stand out like a gaping sore on the landscape. When I get to my hotel, the telephone and electricity don't work due to technical faults across the city, and my room looks no better than a prison cell. The mattress is saggy and foul, but luckily I brought a mosquito net that has been soaked in insecticide.

At the courtyard restaurant, I watch the news in French while trucks full of solders drive by. I feel a gentle tap on my shoulder. “Hello, my name is Christopher. Are you English?” says the young teenage boy in the Arsenal shirt. He asks if I can read him a letter written in English before inviting me to eat with his family. “Our good friend Fidel the priest is going to join us and you are most welcome.” When I meet Fidel, he shakes my hand. “You must be a journalist for God first!” he warns me. “And you will need a photo-permit to take photos in Congo or you will be arrested.”

Sitting on the balcony trying to find the BBC World Service on my radio later that evening, we are joined by their next-door neighbour, Felix, who's from Spain. As soon as we get a signal, the newsreader announces that the civil war in Congo has begun.

A few days later, Fidel and I are at the Ministry of Information to pick up my permit. On our way out, we walk around the back of the building taking a short cut to the sports stadium. Teenagers and small, pygmy men in red headbands are doing army drills, while the place is packed with a pro-Kabila rally. “This is the brave new Congo we have been talking about my friend!” Fidel shouts. “Kabila wants Congo’s wealth for Congo people!” I’ve nearly shot one roll of 35mm film. In the distance, soldiers are running. As the soldiers come nearer, I raise the camera and take a few frames. Suddenly, I feel a huge whack on the side of my head and I collapse to the ground.

Advertisement

Looking up, I see soldiers standing over me, grinning with their rifles pointing to my head. Fidel waves my photo permit at them but another soldier punches him hard in the face. The hostile crowds jeer and spit at us as we are hauled into the middle of the road and dragged down a siding off the main track, ordered to kneel and put our hands behind our heads. The soldier cocks his rifle and presses the muzzle hard into my skull.

It takes him forever to pul the trigger, and when he finally does I am still alive. He laughs and wraps a pair of ropes around our necks, before dragging us to a huge totem pole at the gate of the Ministry. They pin Fidel to the ground, ripping his shirt off, and whip him with knotted rope and brass buckle belts. Fidel screams for his mother as the blood trickles down his back. Soldiers slap Christopher hard across the face and spare him a flogging. And now it's my turn. They order me to remove my trousers. Congo is so hot and muggy, I decided not to wear any underwear. When the soldiers see this, they kick and punch us all the way to the entrance of the Ministry.

Once inside, we are led down a dark, flooded corridor and I can't help but wonder if we are being taken to a torture chamber. We finally arrive in a large room furnished with low leather couches, where the soldiers go through my belongings. Sat in one corner is man in a dark suit scribbling notes on a piece of paper, while another taller man informs me that I’m being charged with espionage. As soon as they are done, we all walk outside to the waiting 4x4 Toyota Jeep and drive through the darkness in complete silence. Finally, the moon sets on a large, concrete buliding and the car stops. We enter, and before we are shown to our "quarters", we are asked to give our names to a man sat behind a desk illuminated by candlelight. We sleep on the floor, exhausted.

Advertisement

The next morning, I'm awaken by a roll call and realise we are in a prison cell packed with men. One of them is South African. He walked all the way to Kinshasa barefoot, only to be jailed as soon as he crossed the border. A lot of them are Rwandans – apparently the prison guard can tell by pinching the skin on their forearms. He takes me on a "tour" of the prison, because I’m a journalist. One cell houses 30 men, and its walls house their faeces.

That night I try to sleep, but the constant buzzing of mosquitoes in my ears is making it hard. There's also a pregnant woman sleeping very close to me so she can keep warm. In the daytime, she is made to sweep the reception room clean, brushing the floor with a cut down broomstick.

The next morning, guards take Fidel, Christopher and myself for further questioning. Christopher translates my English to French; Fidel translates his French to Congolese. The room is crammed full of men in suits, soldiers and young Rwandans who are made to sit cross-legged under tables. My confession papers get passed all over the room. “You have done well with your confession,” says a man who calls himself the "commander". He then takes me to his parked Jeep outside.

We drive through the city streets and eventually stop at a hotel where a large man dressed in a black commando outfit awaits. He introduces himself as the "big chief". He asks me to empty my bag. I stay calm for most of the time, but when he asks if there are any more photographs I have taken, I slightly panic. “If you have,” he says quizzingly, “you will go back to prison immediately.” I deny having taken any more photographs, but a few rolls of film are on the desk in my hotel room. “Okay, we search your hotel room,” he says, irritated.

Advertisement

I'm pushed to enter my room at gunpoint and I immediately place my bag on top of the exposed film. Big chief and his henchmen search everything, looking for money, and never once lift it off the table. Sweat pours from my forehead. “Don’t be scared,” the Big Chief says, waving his pistol in my face. “You should also give me your business card – I would like to visit you in London one day.”

The next day, I join Felix and a nun from a Catholic missionary – who is supposed to help us fly out of Kinshasa – for breakfast. A few hours later, we meet the Spanish ambassador in Kinshasa, who drives us to the ferry port. "Le Beach Ngobila" is packed with mad men and women, screaming and shouting. Queuing systems do not exist here, so the security guards whip people to keep them in line.

We sail across the Congo River and as we get closer to Brazzaville, the passengers all push to the front. A white photographer with a big lens stands alongside French soldiers on land. Once I put my luggage on the ground, TV crews surround me. They want an interview with the "Western journalist who had been tortured".“Were you scared?” they asked me.

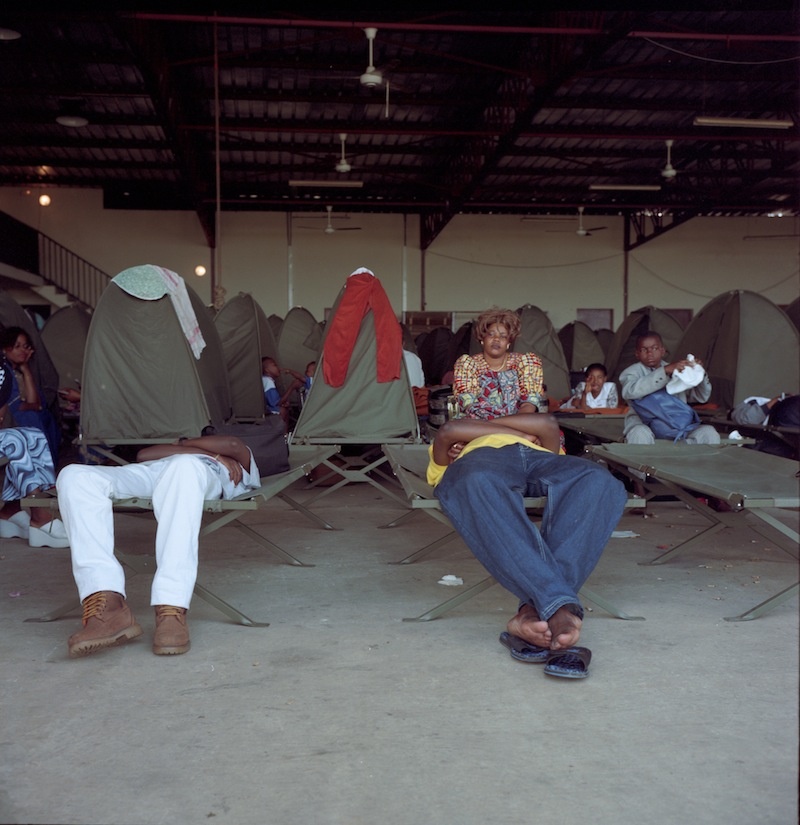

Suddenly I hear someone calling my name through a megaphone. “We heard all about your treatment, Mr Griffiths, and everything has been arranged for a flight to London.” A French army officer approaches me, takes me to a refugee camp in Libreville and hands me a bottle of Pilsner. “You know, it’s only a matter of time until the missiles strike Kinshasa and sort them out for good.” I sip the cool beer and listen. “Kabila’s army are scared, they will desert their leader soon.” The beer goes down well, but the French officer makes me feel uneasy.

Advertisement

A week later, I board the flight to Paris from the refugee camp in Libreville. Back in London, I file a story detailing my arrest for the "world section" of a newspaper. A while later, I travel to the Alentejo region of Portugal, where I'll write the first of many drafts of my book, Pigs Disco. But that’s another story.See more of Stuart Griffiths' work here.Want to find out more about Congo?WATCH – The VICE Guide to CongoThe M23 advance Through Congo as Innocents Run for Their LivesMy Friends Started a Bus Company in the Congo