Gunmaker Richard Giza with a schematic of his recoil-free rifle. Photo by the author

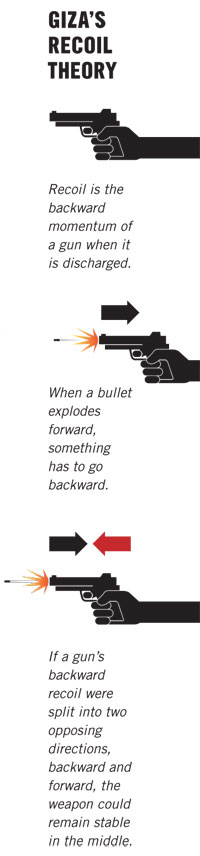

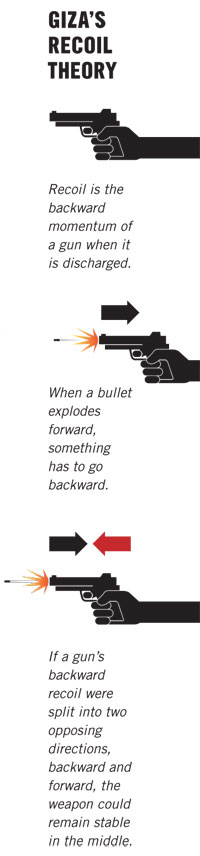

At the turn of the millennium, an amateur gunsmith living in Australia claimed to have achieved the impossible. To the quiet amusement of weapons engineers around the world, Richard Giza, the Polish co-founder of Recoilless Technologies International, announced that he'd built a mechanism that eliminated recoil from firearms.Recoil is the kickback felt when firing a gun. The stronger the gun, the bigger the pulse and the greater the chance of hitting something other than your target. To those in the weapons industry, eliminating it would be a Holy Grail scenario, leading to better accuracy and larger payloads. In terms of achievability, it's up there with nailing cold fusion and inventing time travel.This didn't bother RTI. By 2001, the company was briefing Australian defense scientists and working alongside gun manufacturers like Glock and Beretta. In January 2006 Peter Dunn, an Australian retired major general, told the Age newspaper that RTI had "the potential to fundamentally transform the way ballistic weapons are deployed." The firm was sitting on millions in investment dollars, its success all but assured.Fast-forward to December 2013, and Giza was starving himself on the steps of Melbourne's Parliament House. This was a hunger strike, and it wasn't his first. Giza's company was being liquidated and every vestige of his illustrious future had come undone. He and his colleagues had, in a sense, shot themselves in the foot.Giza was born in western Poland in March 1955. His earliest memories are of his father conspiring with Poland's underground anti-communist resistance, the Z.ołnierze Wykle'ci, or Doomed Soldiers. "I would stay awake and listen," he says of his dad's secret meetings. "The idea of revolution was normal for me, and that's just how I grew up." In 1967 his father's branch of the Doomed Soldiers came undone, forcing the family to settle in Australia, where Giza had an uncle. And while late-60s Melbourne was livelier than Soviet-era Poland, the future inventor kept to himself. "The other boys would go to discotheques while I'd stay home to read text books," he recalls. "Military magazines, physics, and technology—that's all I cared about." At the age of 13 he read about Leonardo da Vinci's design for a recoilless cannon, and it stuck in his imagination.The next 25 years passed without incident. Giza married, had children, and worked a series of shitty jobs in both Poland and Australia. He continued to read about ballistics technology and play around with numbers, equations, and designs, but it never went further than theory.Then, in 1992, when Giza was working at a Melbourne metals foundry, he fell out with the union and management sacked him. Unemployment is a hard knock for any father, but Giza met it by staging a hunger strike against the government, which he blamed for his situation. "I was thinking of my favorite hero, Mahatma Gandhi, and he'd done things like that," he explains, grinning. "Actually we'd done things like that in Poland too, but much shorter."The strike worked and City Council found him a job, but he and his wife divorced. "My wife and kids always suffered because of my revolutionary activities. We were together and separated, then together again, then finally separated, but people can't stop you from fighting for your rights."The next hunger strike came in 1996. That year a mentally handicapped loner named Martin Bryant shot 35 people in Tasmania, and the Australian government banned a wide range of weapons. "Disarmament! The government wanted to leave people unable to defend themselves," Giza recalls, still incredulous. He commenced another hunger strike on the steps of Parliament, and made a decision to pursue his oldest passion: firearms. Since 13 he'd dreamed of small weapons with immense payloads—handguns that fire 20mm rounds and aircraft that pack the wallop of tanks. Since he was jobless and single, he had more time than ever.Giza sold his house and rented a workshop. The problem of recoil lies in the fact that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. A bullet explodes forward and something has to go backward. Giza's thinking was that if a gun's backward recoil were split into two opposing directions, backward and forward, the weapon could remain stable in the middle. This would happen if an equal amount of exploding gas were forced forward as back, causing two spring-loaded components of the gun to separate from the center. In his own words, "the gun is effectively being blown apart and the bullet leaves as a side effect." By 1998, after two years of refurbishing a .22 magnum, he had a working prototype.Joseph Vella is a stocky Maltese mechanic who owned the garage next door. By some twist of fate, he was a shooting enthusiast who, as Giza recalls, "would always say hello and have lots of questions." When asked to remember the first time he saw the gun, Vella's eyes light up. "I couldn't believe it," he says. "I knew right away."The pair went into business and incorporated RTI on March 23, 2000. By Giza's estimate, they received $9 million in investments over the decade, but Singapore's interest was the kicker. Several members of the country's defense ministry visited RTI's workshop in 1999, which is a moment captured on YouTube. You can see the officials watching a modified Mauser 98 bolt-action rifle suspended by four free-hanging steel cables. A shot is fired and the rifle sways gently in the wires. There's no jolt.

In 1967 his father's branch of the Doomed Soldiers came undone, forcing the family to settle in Australia, where Giza had an uncle. And while late-60s Melbourne was livelier than Soviet-era Poland, the future inventor kept to himself. "The other boys would go to discotheques while I'd stay home to read text books," he recalls. "Military magazines, physics, and technology—that's all I cared about." At the age of 13 he read about Leonardo da Vinci's design for a recoilless cannon, and it stuck in his imagination.The next 25 years passed without incident. Giza married, had children, and worked a series of shitty jobs in both Poland and Australia. He continued to read about ballistics technology and play around with numbers, equations, and designs, but it never went further than theory.Then, in 1992, when Giza was working at a Melbourne metals foundry, he fell out with the union and management sacked him. Unemployment is a hard knock for any father, but Giza met it by staging a hunger strike against the government, which he blamed for his situation. "I was thinking of my favorite hero, Mahatma Gandhi, and he'd done things like that," he explains, grinning. "Actually we'd done things like that in Poland too, but much shorter."The strike worked and City Council found him a job, but he and his wife divorced. "My wife and kids always suffered because of my revolutionary activities. We were together and separated, then together again, then finally separated, but people can't stop you from fighting for your rights."The next hunger strike came in 1996. That year a mentally handicapped loner named Martin Bryant shot 35 people in Tasmania, and the Australian government banned a wide range of weapons. "Disarmament! The government wanted to leave people unable to defend themselves," Giza recalls, still incredulous. He commenced another hunger strike on the steps of Parliament, and made a decision to pursue his oldest passion: firearms. Since 13 he'd dreamed of small weapons with immense payloads—handguns that fire 20mm rounds and aircraft that pack the wallop of tanks. Since he was jobless and single, he had more time than ever.Giza sold his house and rented a workshop. The problem of recoil lies in the fact that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. A bullet explodes forward and something has to go backward. Giza's thinking was that if a gun's backward recoil were split into two opposing directions, backward and forward, the weapon could remain stable in the middle. This would happen if an equal amount of exploding gas were forced forward as back, causing two spring-loaded components of the gun to separate from the center. In his own words, "the gun is effectively being blown apart and the bullet leaves as a side effect." By 1998, after two years of refurbishing a .22 magnum, he had a working prototype.Joseph Vella is a stocky Maltese mechanic who owned the garage next door. By some twist of fate, he was a shooting enthusiast who, as Giza recalls, "would always say hello and have lots of questions." When asked to remember the first time he saw the gun, Vella's eyes light up. "I couldn't believe it," he says. "I knew right away."The pair went into business and incorporated RTI on March 23, 2000. By Giza's estimate, they received $9 million in investments over the decade, but Singapore's interest was the kicker. Several members of the country's defense ministry visited RTI's workshop in 1999, which is a moment captured on YouTube. You can see the officials watching a modified Mauser 98 bolt-action rifle suspended by four free-hanging steel cables. A shot is fired and the rifle sways gently in the wires. There's no jolt. Noting Singapore's interest, the Australian military signed a non-disclosure agreement with RTI, asking the firm to brief its scientists. A similar deal with Poland followed. This inspired discussions with the German manufacturer Glock, after which Vella used his shooting contacts to hash out a collaborative deal with Beretta. Vella also claims that an executive from United Defense (which became part of BAE Systems) visited them in the mid 2000s and later admitted that he was there to steal RTI's designs.Despite the innovative technology, Giza and Vella's business decisions were unwaveringly abysmal. In 2004 the Australian Securities and Investments Commission discovered that RTI had raised their initial capital from Vella's friends and family without legislated disclosures on risk. They deemed this "misleading or deceptive" and forced the company to return $600,000 in funds or shares.After this debacle, Giza and Vella sought to get RTI some business acumen with a smooth-talking director by the name of Andrew Flanagan. But exactly five months later Flanagan initiated legal proceedings to have the company shut down. An investigation by the Australian later found Flanagan was a repeat con artist wanted by several governments around the world.RTI somehow survived, only to report an operational loss of $2.7 million in 2006, trailed by a $4.8 million loss the following year. According to Giza, the company's R&D simply cost more than they raised, but Valla is far more forthcoming: "It was our board treating themselves, flying everywhere first class." This all came to a head in 2007 when most of the company's investors walked, leaving the founders to go down with the ship. The end came in 2009, when Giza was diagnosed with colon cancer. By the time he'd beaten it, RTI had lost everything.In December 2013, Giza and Vella applied for government welfare. "We had no money for food," Giza explains. "And Joseph can't write, so I had to fill in his forms." This led to a heated argument with the welfare officer, and the two men were escorted from the building. A few days later, Giza was back on Parliament's steps for his third hunger strike. For three months he lived on nothing but salt, sugar, and water, losing 92 pounds in the process. Finally the government relented and has paid for his hostel lodging ever since."What was it all about?" Giza repeats my last question with a certain smugness, like he anticipated my asking it. "Forget about money," he says. "It's about solving problems created by motion." I think he means motion in a physics sense, but it's an ambiguous statement. Maybe Richard Giza just likes a fight.

Noting Singapore's interest, the Australian military signed a non-disclosure agreement with RTI, asking the firm to brief its scientists. A similar deal with Poland followed. This inspired discussions with the German manufacturer Glock, after which Vella used his shooting contacts to hash out a collaborative deal with Beretta. Vella also claims that an executive from United Defense (which became part of BAE Systems) visited them in the mid 2000s and later admitted that he was there to steal RTI's designs.Despite the innovative technology, Giza and Vella's business decisions were unwaveringly abysmal. In 2004 the Australian Securities and Investments Commission discovered that RTI had raised their initial capital from Vella's friends and family without legislated disclosures on risk. They deemed this "misleading or deceptive" and forced the company to return $600,000 in funds or shares.After this debacle, Giza and Vella sought to get RTI some business acumen with a smooth-talking director by the name of Andrew Flanagan. But exactly five months later Flanagan initiated legal proceedings to have the company shut down. An investigation by the Australian later found Flanagan was a repeat con artist wanted by several governments around the world.RTI somehow survived, only to report an operational loss of $2.7 million in 2006, trailed by a $4.8 million loss the following year. According to Giza, the company's R&D simply cost more than they raised, but Valla is far more forthcoming: "It was our board treating themselves, flying everywhere first class." This all came to a head in 2007 when most of the company's investors walked, leaving the founders to go down with the ship. The end came in 2009, when Giza was diagnosed with colon cancer. By the time he'd beaten it, RTI had lost everything.In December 2013, Giza and Vella applied for government welfare. "We had no money for food," Giza explains. "And Joseph can't write, so I had to fill in his forms." This led to a heated argument with the welfare officer, and the two men were escorted from the building. A few days later, Giza was back on Parliament's steps for his third hunger strike. For three months he lived on nothing but salt, sugar, and water, losing 92 pounds in the process. Finally the government relented and has paid for his hostel lodging ever since."What was it all about?" Giza repeats my last question with a certain smugness, like he anticipated my asking it. "Forget about money," he says. "It's about solving problems created by motion." I think he means motion in a physics sense, but it's an ambiguous statement. Maybe Richard Giza just likes a fight.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement