FYI.

This story is over 5 years old.

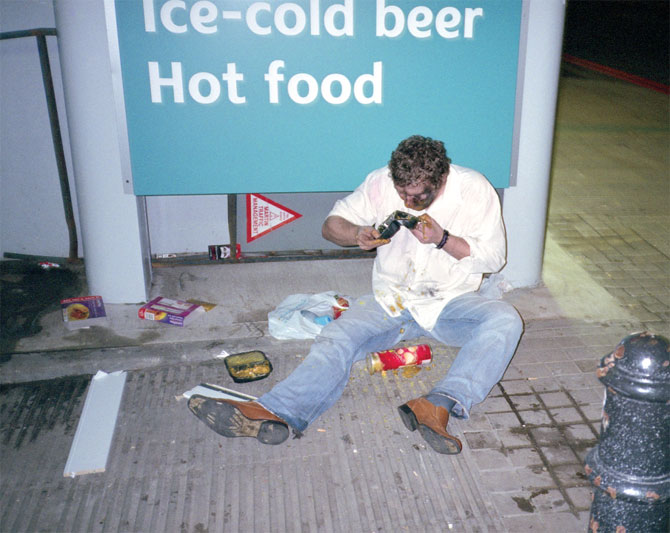

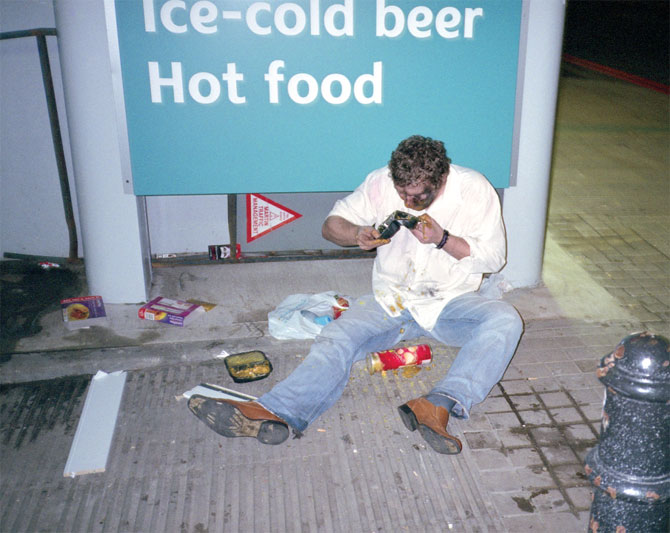

Vice Fiction - My Appetite

I began stealing when I was twenty-two. The first thing I stole was a chocolate muffin. I started eating it on my way round the supermarket and finished it before I got to the till. From then on, whenever I did my weekly food shop, I'd steal something.