Harry Gould Harvey IV may sound like the name of an old sailboat pegged as an underdog in a gentleman’s race around the world, but in reality it’s what a family in Rhode Island has been naming their sons for generations. The fifth iteration of that series is a photographer who loves punk, making trap playlists, and playing pranks. Harry’s surreal twists on reality have been compiled in the fantastic books One, Mountain Pass,and Canadian Fruit, as well as in large commercial publications like the Fader, JUKE, and Bloomberg’s Business Week. At a time when it feels like everywhere you look one photo just indiscernibly scrolls into the next, we think his dreamy and ethereal pictures are worth a close read, so we wanted to ask him more about them, even if interviewing someone isn’t very punk.

Advertisement

VICE: What would you rather be doing than talking to me right now?

Harry Gould Harvey IV: I have extreme anxious tendencies that I deal with through art. If there’s a big social gathering I’d rather be working on stuff or hanging out drinking a 40.When did you start taking photos?

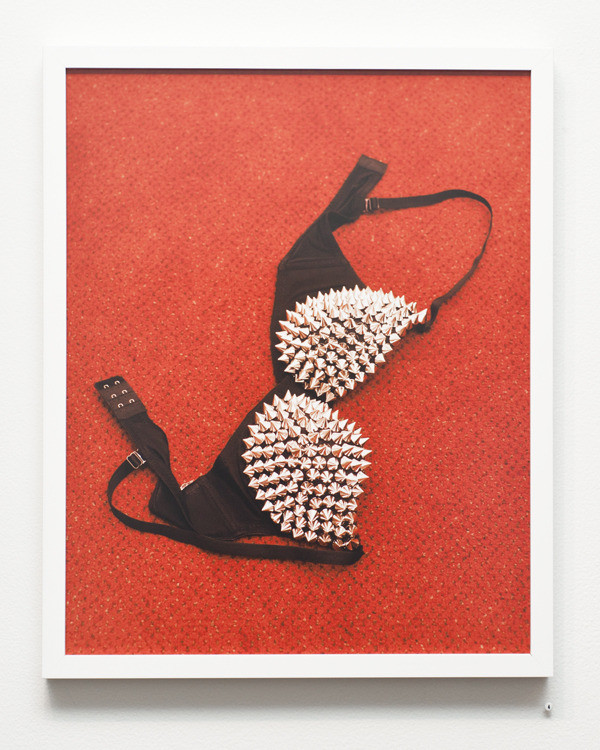

I’ve been taking photos as long as I can remember. I initially started documenting my friends playing in hardcore and punk bands. The photographs weren't live show shots—they were just focused on the culture. From there, when I was 15 or 16, I started making more conceptual work about the culture and that’s what led me here.Your book One focuses on punk subculture, and it portrays a loneliness and alienation within that lifestyle. Was that something you intentionally set out to show?

Yeah. One addresses my inability to identify sexually as a gender or have a sexual orientation, which I think is a very lonely aspect of finding yourself. It’s through punk that I’ve been able to express that. I don’t identify as gay or straight or anything, I just kind of am a human being, and with punk culture I feel like it’s one of the only cultures that I’m a part of that is, like, Yeah, of course that’s the way it is. So that’s kind of a lonely quest and that’s an aspect that the work hopefully addresses. That’s where the starkness or the singularity comes from that could be seen as a loneliness.What was the first photo you took with intentionally artistic purposes?

I think there’s actually one of the photos that I took in my first project, which was a project on Newport, Rhode Island, called High Society. It was a photo of an adult video store sign on a plain blue sky, a very simple photograph. The feeling I got seeing it made me realize I want to make all my photographs look like that—stripped down and simplified. That was the one where I realized I want to work in a body of work, and I want to make every individual image as strong as I can.

Harry Gould Harvey IV: I have extreme anxious tendencies that I deal with through art. If there’s a big social gathering I’d rather be working on stuff or hanging out drinking a 40.When did you start taking photos?

I’ve been taking photos as long as I can remember. I initially started documenting my friends playing in hardcore and punk bands. The photographs weren't live show shots—they were just focused on the culture. From there, when I was 15 or 16, I started making more conceptual work about the culture and that’s what led me here.Your book One focuses on punk subculture, and it portrays a loneliness and alienation within that lifestyle. Was that something you intentionally set out to show?

Yeah. One addresses my inability to identify sexually as a gender or have a sexual orientation, which I think is a very lonely aspect of finding yourself. It’s through punk that I’ve been able to express that. I don’t identify as gay or straight or anything, I just kind of am a human being, and with punk culture I feel like it’s one of the only cultures that I’m a part of that is, like, Yeah, of course that’s the way it is. So that’s kind of a lonely quest and that’s an aspect that the work hopefully addresses. That’s where the starkness or the singularity comes from that could be seen as a loneliness.What was the first photo you took with intentionally artistic purposes?

I think there’s actually one of the photos that I took in my first project, which was a project on Newport, Rhode Island, called High Society. It was a photo of an adult video store sign on a plain blue sky, a very simple photograph. The feeling I got seeing it made me realize I want to make all my photographs look like that—stripped down and simplified. That was the one where I realized I want to work in a body of work, and I want to make every individual image as strong as I can.

Advertisement

How do you switch from taking photos of the punk scene to doing commercial work for a business mag like Bloomberg?

It's actually pretty simple for me, because the photos that are in this body of work have this very commercial aesthetic. I hope what comes through is the commodification of punk, which is why some of the paintings have registered trademarks and all these logos and signs that deal with the sale of culture. The style that informs a photograph is very commercial, so it makes sense that I’m able to take this extremely commercial, well-lit, polished photo and just change the subject. I like the challenge of being able to work for a client while still doing whatever the fuck I want but still fill their needs.

It's actually pretty simple for me, because the photos that are in this body of work have this very commercial aesthetic. I hope what comes through is the commodification of punk, which is why some of the paintings have registered trademarks and all these logos and signs that deal with the sale of culture. The style that informs a photograph is very commercial, so it makes sense that I’m able to take this extremely commercial, well-lit, polished photo and just change the subject. I like the challenge of being able to work for a client while still doing whatever the fuck I want but still fill their needs.

Harry Gould Harvey IV. Photo by Aaron Wynia

Have you had any strange requests from CEOs on a job?

It’s funny, because they all kind of perpetuate a style or a way they want to look, but a lot of the time I’m trying to get a more awkward photo for them. For Bloomberg they usually want a "unique" perspective. A lot of times if I were to show them the photos I was taking they would probably be pretty upset. There are times when I have to change people's perspectives of themselves.Whom do you consider an influence?

There are obvious contemporary photographers I love and admire, like Roe Ethridge, or the way that Ron Jude bounces back and forth between formats. But my strongest influences are my peers. It’s a group of people I’m trying to build up and support as much as they do to me. If people have any interest in who that may be—like on social media, which I think is a great tool for photography—we’re constantly building one another up. I think that’s the best way to see who my influences are.

Have you had any strange requests from CEOs on a job?

It’s funny, because they all kind of perpetuate a style or a way they want to look, but a lot of the time I’m trying to get a more awkward photo for them. For Bloomberg they usually want a "unique" perspective. A lot of times if I were to show them the photos I was taking they would probably be pretty upset. There are times when I have to change people's perspectives of themselves.Whom do you consider an influence?

There are obvious contemporary photographers I love and admire, like Roe Ethridge, or the way that Ron Jude bounces back and forth between formats. But my strongest influences are my peers. It’s a group of people I’m trying to build up and support as much as they do to me. If people have any interest in who that may be—like on social media, which I think is a great tool for photography—we’re constantly building one another up. I think that’s the best way to see who my influences are.

Advertisement

Do you think Instagram has made you more competitive as a photographer?

Definitely. I mean the internet has certainly helped me sustain a living. I’ve been working full time as a photographer for about a year now and without the internet; I know that wouldn’t have been a possibility. I mean, I’m a high school drop out. How else would my work have gotten into these people's hands? It's definitely made the market more competitive, but also more saturated. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It makes you have to weed through things a little more.What was your last job before full-time photography?

I’ve always had random hustles. The last job that I did consistently was antique restoration. Restoring really expensive bougie tables for a shop in Rhode Island. I always did random things—like shitty graphic design, even though I don’t do graphic design, or side jobs like painting radiators or working on a car. Anything really, as long as I got paid enough money.For your book Mountain Pass, you got very close to the world of street racing. How did you get involved in that scene?

I became interested in the way that white boys are fascinated with street racing, Japanese girls, import models—just the way they lust after that culture. I started to go to these meets, which I had access too because my older sibling is pretty deep into the street racing scene in the northeast and has a Honda Civic that she’s put 20 grand into. Her and her boyfriend brought me to the races and there were times when we had to run from the cops. It was pretty intense, but I owe it to her for allowing me to be submerged in the culture.

Definitely. I mean the internet has certainly helped me sustain a living. I’ve been working full time as a photographer for about a year now and without the internet; I know that wouldn’t have been a possibility. I mean, I’m a high school drop out. How else would my work have gotten into these people's hands? It's definitely made the market more competitive, but also more saturated. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It makes you have to weed through things a little more.What was your last job before full-time photography?

I’ve always had random hustles. The last job that I did consistently was antique restoration. Restoring really expensive bougie tables for a shop in Rhode Island. I always did random things—like shitty graphic design, even though I don’t do graphic design, or side jobs like painting radiators or working on a car. Anything really, as long as I got paid enough money.For your book Mountain Pass, you got very close to the world of street racing. How did you get involved in that scene?

I became interested in the way that white boys are fascinated with street racing, Japanese girls, import models—just the way they lust after that culture. I started to go to these meets, which I had access too because my older sibling is pretty deep into the street racing scene in the northeast and has a Honda Civic that she’s put 20 grand into. Her and her boyfriend brought me to the races and there were times when we had to run from the cops. It was pretty intense, but I owe it to her for allowing me to be submerged in the culture.

Advertisement

The photos project a fantasy, cartoonish element, like looking through a manga comic, and the women become an object as much as the cars do. Were you looking to draw these connections?

That’s the kind of language I was interested in. Women are objectified in the culture, which I think is shitty, but there’s always an underlying sexual current in my work, whether it’s heterosexual or not. The fantasy and the ability to create a context that isn’t reality is something I’m always attracted to, and I think that’s why I portrayed it in that manner.If you're in Canada, Harry Gould Harvey IV's latest work, Demo (2014), is on display at Working Title (126A Davenport Road) in Toronto until early June.

That’s the kind of language I was interested in. Women are objectified in the culture, which I think is shitty, but there’s always an underlying sexual current in my work, whether it’s heterosexual or not. The fantasy and the ability to create a context that isn’t reality is something I’m always attracted to, and I think that’s why I portrayed it in that manner.If you're in Canada, Harry Gould Harvey IV's latest work, Demo (2014), is on display at Working Title (126A Davenport Road) in Toronto until early June.

Harry Gould Harvey IV

Harry Gould Harvey IV

Harry Gould Harvey IV

Harry Gould Harvey IV

Harry Gould Harvey IV