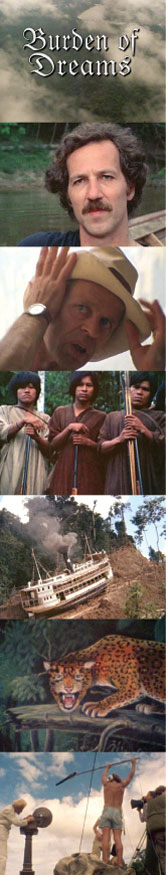

LES BLANK

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement