Advertisement

Mclean Stephenson: We covered a lot of ground on this trip—starting in France. We went to the Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey, spending days travelling through ancient towns and the ruins of post-communist industrial sites. Most of the photography was done in Transylvania, Sophia and Istanbul. Oh, and we were there on our honeymoon, my wife and I.

In terms of photographs: Bulgaria. Sophia in particular, being one of the most bewildering, inexplicable places I’ve ever visited. At first glance the place seems ordinary enough, but the more you look the stranger it gets. Like the dogs–the city is full of them. So is Bucharest, but there are more dogs in Sophia. They don’t have owners and they roam about in packs. Apparently a lot of them are rabid. They sleep on the sidewalks and die there too. People just step over them, they are so used to it.

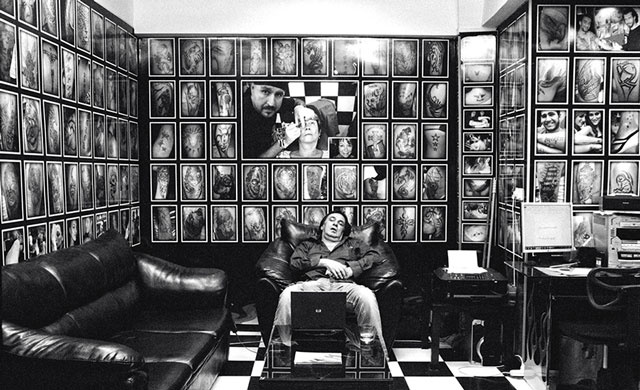

My favourite shot wasn’t taken in Bulgaria; it was taken in Kusadasi, a region on the Aegean coast of Turkey. It’s the picture of the guy sleeping in the armchair in the tattoo parlour. The parlour was down an alley in a really bad part of town and it was late at night. I saw the shot and I thought, “I’ve got one go at this before someone sees me”. I didn’t have time to adjust the exposure properly, so I guessed. The second after I took it the guy woke up and started yelling at me. Then two other guys joined in. I thought it was curtains. So I was fairly happy when I developed the roll and saw that I made the shot.

Advertisement

Whenever I'm exposed to a new culture or place I unconsciously establish points of difference with my own background. I think we all do that. Similarly, if I'm walking through a slum, I'll be conscious of my privileged life. I have been involved in some really strange situations though.Like last year in a café in Istanbul I was putting ice on my ankle—I'd got stung by a wasp—when a gay couple came up and asked if I would photograph them. They were an odd pair: a little Indian guy and a really obese Turkish guy. They led me around the back of the cafe to this small enclosure that was full of rubbish and then started kissing and getting really intimate. I photographed them for about 20 minutes and the whole time they were holding up their iPhones because the iPhone symbolises a degree of wealth. I suppose they wanted the viewer to know that even though they were going at it in a pile of rubbish, they weren’t poor.When something like that happens it does cause me to question who I am and what I consider to be “normal”.

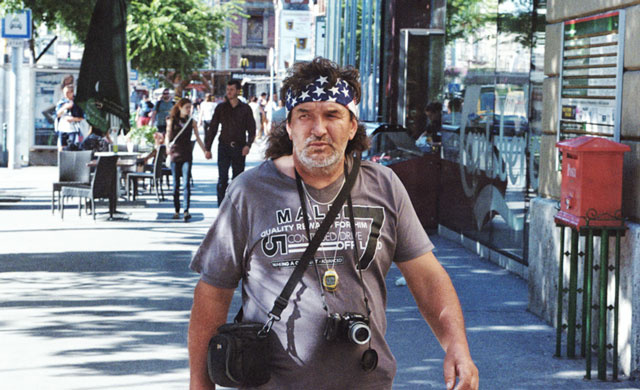

Nobody really spoke any English, so it was hard. Often I’d ask someone if I could photograph them by pointing at them and my camera and they would just stare at me, probably wondering if I was unwell. Other times I’d take a photo of someone and they would see me and walk over to talk to me and then, when they realised I couldn’t speak the language, we’d enter into this weird sign language dance thing. Overall, people didn’t seem to mind being photographed. It’s very different from here.

Advertisement

A lot of the places we went aren’t set up for western tourism, probably because there is very little demand for it. While there is western influence it’s not overly widespread. In the cities the specter of communism is everywhere, particularly in the architecture. Rows and rows of identical, panel buildings. And then there are the traditional, national cultures, which are very prevalent. So you’ve got western culture, the national culture, and strong remnants of Communism all happening at once.Outside the cities it’s different. People lead traditional agrarian style, self-sufficient lives. The small townships are like villages really, with an ancient church and an Inn. The people get about on donkey-drawn carts and grow their own food. In Moldovia (Romania), they worship Vlad the Impaler. People light candles in front of portraits of him in churches. The first time I saw that I got confused and thought, “why is that old lady praying to Dracula?” I didn’t realise that he is considered a national hero—a great king who repelled the Turks. The whole vampire thing, Bram Stoker did that.

Advertisement

Advertisement

It’s probably both. Isolation isn’t a theme that I consciously pursued, but it’s one that people have identified in these pictures. I mentioned before that when I’m exposed to a new culture or place I establish points of difference. Well, I think it’s those things that strike me as spatially or culturally different that I’m often compelled to photograph. From our point of view, the cities of Eastern Europe can be fairly bleak. And it’s probably true that the bleaker, less familiar places, the places that differed most from my life here, inspired a lot of the photographs I took.

The differences are enormous. For me photographing a friend is a kind of intimate, private process that happens up close. It involves trust and a common narrative. Also, because I know the person, I’m able to prepare for the process and I generally know what it is that I’m trying to capture. Time plays a big role – I can photograph a friend for hours before I’m ready to stop.With a complete stranger it happens quickly, in a blur of movement. There is no common narrative or purpose because the event is completely random. All I feel is urgency—the urgency of setting the exposure and composing the frame in the small window of time I have. Later when I develop the film, I see these strangers looking at me and I’m left wondering who they are, what kind of past they had, what kind of life they lead.

Advertisement

I do consider myself a storyteller of sorts, although I’m reluctant to use the term. Every photograph I take is the result of a conscious act. And then after taking a series of photographs I spend a lot of time deciding what to keep and what to discard. So the end product —the “story”—is the result of a number of decisions. I’m reluctant to use the term “story” because as a photographer I’m more focused on themes than narratives. And I think of my subjects as expressions of a theme or idea. Of course, I’m aware that my subjects have stories that exist outside the photographs, however those stories are unknown to me.What else have you got coming up?

I’ve got a lot on. I’m finishing a series of nudes and landscapes for a book/show that I’m organising at the moment. There’s my commercial work, the stuff I shoot for money, which takes up a lot of time. And I’m planning a photo trip to China at the end of the year. Oh, and we are getting dog.Follow Josh on Twitter: @Josh__GardinerSee more of Mclean's work here or check him out on Instagram.