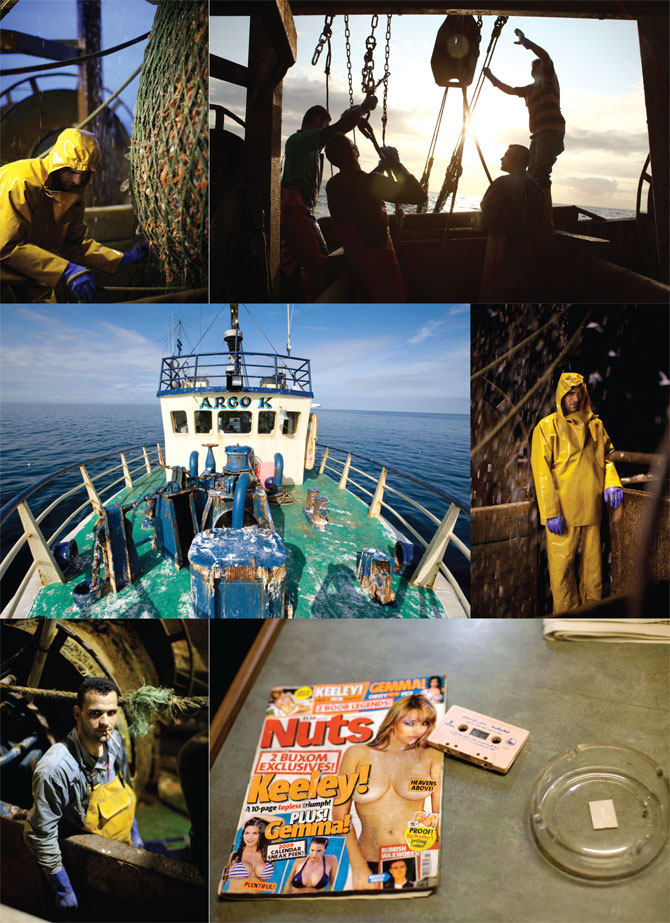

BY CONOR CREIGHTON, PHOTOS BY STEVE RYAN It’s important that the last woman you see before you board a fishing trawler is reasonably hot. She doesn’t need to be knock-you-down gorgeous—she just needs to look like she’d do for a wee shag and a cuddle on a cold night. You need to try your hardest to burn her image into your retinas, because after a week at sea surrounded by nothing but smelly men, saltwater, and dead fish, the memory of her and the faint hope that she might be walking along that exact same pier when you return—maybe waiting just for you in those same jeans that made her arse look like a couple of queen potatoes in a swimming cap—will be the only thing that keeps you from throwing yourself overboard from boredom and frustration.The fishing vesselArgo Kmoors in a small harbor to the north of Dublin called Howth. Howth is famous for couples. There’s a little piece of headland and a windy lane, and that’s where they go late at night to watch over the bay and the city lights and fish around in each other’s pants. Meanwhile, theArgo Kleaves the bay every week to go fishing for prawns. It fishes in the most radioactive sea in Western Europe, off the coast of the Sellafield power plant—Britain’s only nuclear plant. Its two towers face onto the Irish Sea like a giant “fuck you.” And in an amazing coincidence, the Irish town directly across from the nuclear plant has the highest rate of cancer and disabled children in the whole country. Weird!It’s no big deal to the fishermen, though. “Sure you might find a few three-eyed haddock in the hopper if we go over there,” says Adrian, the skipper of theArgo K. “You find some quare fish over there all right, but sure you find quare fish everywhere these days.”Adrian is from North Donegal. He never sleeps. He’s only 30, and he’s skinny like a teenager—that’ll be all the instant coffee and roll-ups in his diet. At most he gets two hours every couple of days, but you know that he’s just tossing and turning, awake in his bunk, thinking about what the prawns might be doing. Adrian is a career fisherman. On land he does stupid things like ram police cars and get his license taken away from him, but at sea he’s a wise old hunter who smells his way to the prey and pulls in two-ton hauls when everybody else is catching fuck all. Adrian loves fishing; the six Egyptians that serve as his crew don’t, but it’s the only work they can get away with as illegals. So that’s what they do. They fish for prawns.There’s not much money to be made on fishing boats in Ireland anymore. Wages are still divvied up depending on the profit the boat makes, but it’s not like the old days when fishermen could buy a new car every month just to crash it into a wall. Nowadays the boats go through about a thousand euros in diesel every 30 hours and most of them are so heavily mortgaged that even if they were to fish every day of the month, they’d still not do much more than chip away at the interest.TheArgo Kfishes every day. It has two skippers and it never stops. It just barely touches the harbor wall before a fresh crew and skipper do a swap and take it out again. Consequently, it’s the biggest rust heap in town.“If any boat was out this much it’d look this rusty,” says Adrian. “We used to see theArgoup home when I was a kid and I always thought, ‘What a crock it is.’ Little did I know that I’d be skipper of it one day.” TheArgo Kis a Russian boat from the 80s. The current owner, Adrian’s boss, mortgaged it for a million euros and put his family home up as collateral. This likely means he will be the owner of a rusty old fishing boat until he dies.Life on a fishing trawler is simple. Every six hours the nets are brought in and the catch is processed. The prawns get their heads ripped off before they are thrown into baskets. (Everything else gets dumped overboard—only the crabs and the occasional strong cod are still alive at that stage. The boat leaves behind a mile-long trail of dead fish floating on the surface for the gulls to get fat on.) The processing can take anything up to five hours if your skipper’s hunting well. You’re standing for so long that your ankles swell up to the point where you’ve got to nearly rip your boots off at the end of the shift. Your wrists swell up too and your back goes through short spasms of pain as you try to keep your balance while beheading a thousand prawns. Some of the prawns fight back and bite through your gloves to the flesh, so you crush them and watch them die slowly—that’s the way of the sea, matey. In the remaining hour or so you’ve got before the next haul, you eat, sleep, shit, get stoned, and walk around on deck trying to get phone reception so you can message your girl with a request for something dirty in reply. The Egyptian boys all have Irish girls—they’ve got pictures of them on their mobile phones—big girls with black teeth and IRA tats on their arms.“Irish woman is crazy,” a crew member named Hassan says. “They happy, then they drink so much that they cry, then they drink again and they happy again.” Hassan has a tattoo of a seagull on his bicep done in Indian ink. Above it he has the letter “M” for his mother.

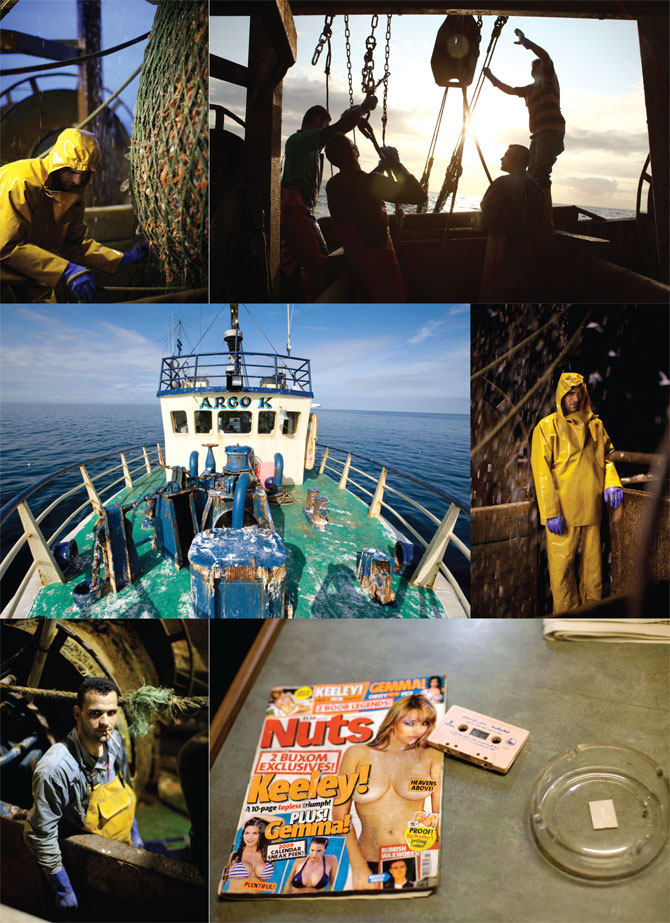

It’s important that the last woman you see before you board a fishing trawler is reasonably hot. She doesn’t need to be knock-you-down gorgeous—she just needs to look like she’d do for a wee shag and a cuddle on a cold night. You need to try your hardest to burn her image into your retinas, because after a week at sea surrounded by nothing but smelly men, saltwater, and dead fish, the memory of her and the faint hope that she might be walking along that exact same pier when you return—maybe waiting just for you in those same jeans that made her arse look like a couple of queen potatoes in a swimming cap—will be the only thing that keeps you from throwing yourself overboard from boredom and frustration.The fishing vesselArgo Kmoors in a small harbor to the north of Dublin called Howth. Howth is famous for couples. There’s a little piece of headland and a windy lane, and that’s where they go late at night to watch over the bay and the city lights and fish around in each other’s pants. Meanwhile, theArgo Kleaves the bay every week to go fishing for prawns. It fishes in the most radioactive sea in Western Europe, off the coast of the Sellafield power plant—Britain’s only nuclear plant. Its two towers face onto the Irish Sea like a giant “fuck you.” And in an amazing coincidence, the Irish town directly across from the nuclear plant has the highest rate of cancer and disabled children in the whole country. Weird!It’s no big deal to the fishermen, though. “Sure you might find a few three-eyed haddock in the hopper if we go over there,” says Adrian, the skipper of theArgo K. “You find some quare fish over there all right, but sure you find quare fish everywhere these days.”Adrian is from North Donegal. He never sleeps. He’s only 30, and he’s skinny like a teenager—that’ll be all the instant coffee and roll-ups in his diet. At most he gets two hours every couple of days, but you know that he’s just tossing and turning, awake in his bunk, thinking about what the prawns might be doing. Adrian is a career fisherman. On land he does stupid things like ram police cars and get his license taken away from him, but at sea he’s a wise old hunter who smells his way to the prey and pulls in two-ton hauls when everybody else is catching fuck all. Adrian loves fishing; the six Egyptians that serve as his crew don’t, but it’s the only work they can get away with as illegals. So that’s what they do. They fish for prawns.There’s not much money to be made on fishing boats in Ireland anymore. Wages are still divvied up depending on the profit the boat makes, but it’s not like the old days when fishermen could buy a new car every month just to crash it into a wall. Nowadays the boats go through about a thousand euros in diesel every 30 hours and most of them are so heavily mortgaged that even if they were to fish every day of the month, they’d still not do much more than chip away at the interest.TheArgo Kfishes every day. It has two skippers and it never stops. It just barely touches the harbor wall before a fresh crew and skipper do a swap and take it out again. Consequently, it’s the biggest rust heap in town.“If any boat was out this much it’d look this rusty,” says Adrian. “We used to see theArgoup home when I was a kid and I always thought, ‘What a crock it is.’ Little did I know that I’d be skipper of it one day.” TheArgo Kis a Russian boat from the 80s. The current owner, Adrian’s boss, mortgaged it for a million euros and put his family home up as collateral. This likely means he will be the owner of a rusty old fishing boat until he dies.Life on a fishing trawler is simple. Every six hours the nets are brought in and the catch is processed. The prawns get their heads ripped off before they are thrown into baskets. (Everything else gets dumped overboard—only the crabs and the occasional strong cod are still alive at that stage. The boat leaves behind a mile-long trail of dead fish floating on the surface for the gulls to get fat on.) The processing can take anything up to five hours if your skipper’s hunting well. You’re standing for so long that your ankles swell up to the point where you’ve got to nearly rip your boots off at the end of the shift. Your wrists swell up too and your back goes through short spasms of pain as you try to keep your balance while beheading a thousand prawns. Some of the prawns fight back and bite through your gloves to the flesh, so you crush them and watch them die slowly—that’s the way of the sea, matey. In the remaining hour or so you’ve got before the next haul, you eat, sleep, shit, get stoned, and walk around on deck trying to get phone reception so you can message your girl with a request for something dirty in reply. The Egyptian boys all have Irish girls—they’ve got pictures of them on their mobile phones—big girls with black teeth and IRA tats on their arms.“Irish woman is crazy,” a crew member named Hassan says. “They happy, then they drink so much that they cry, then they drink again and they happy again.” Hassan has a tattoo of a seagull on his bicep done in Indian ink. Above it he has the letter “M” for his mother. There are two bunkrooms on the boat with four beds in each. They’re blacked out and right next to the engine room so after a day or two of steaming at sea, they’re warm and smelly like saunas. At the end of a shift, you stumble into one and flop wherever you can and hope there isn’t an Egyptian already lying beneath you. There’s no shower and the crew never bothers to change their jocks or socks because everything already stinks of fish. You smoke in bed, you snore loudly, and when you need to pull one off, you do—regardless of whoever’s beneath or above you. The boat is rolling and squeaking enough already, so you probably won’t get caught.The crew were observing Ramadan during our time with them. They set alarms all over the boat so they could wake up and say prayers five times a day, individually. That’s six Egyptians with five alarms each, coupled with the skipper’s alarm to let us know when it was time to haul the nets in. After eight in the evening, we’d all sit down to a feast of the fish that the quotas forbade us from keeping. Sharks, crabs, haddock, black sole, cod, all grilled and boiled and tossed onto plates made out of newspaper. Then we’d all get stoned and listen to Egyptian dance music in a kitchen that was just about small enough to be able to touch both walls when you stretched your arms out. That was the only time the Egyptians ate. Apart from that they went around starving, just munching on cigarettes.Most boats in Ireland are crewed by foreigners. Irishmen won’t work this hard for that kind of money. The crews are Filipino, Egyptian, or Russian. All the skippers want Russians because they’re the sort of meatheads who’d lose a finger, stick it back on with fishing net, and keep on gutting. The Egyptians are a bit softer. Once, one of the crew had to be airlifted off the boat when the anchor winch swung loose and caught him in the ear. He passed out. “You have to more than pass out to get out of work on the boats,” says Adrian. “He was only acting up to go home—and he cost me 1,500 euros for the airlift.” He pauses. “But it can be dangerous sometimes, yeah. Lads lose arms. I heard of a guy who got pulled in two by the net cable. He died, so he did.”After a few days at sea you fall into a rhythm. You remember to stand with the roll of the wave so you don’t smack your head on every doorway. Whenever your hands are free for a second you get your tobacco out and roll a cigarette for later. And if you think you’re going to have more than half an hour to yourself, you head down to a bunk and get some rest.According to the British Secret Service, sleep deprivation is the most effective means of torture there is. Keep anyone awake long enough, until their skin is peeling and their nails are chewed away, and they’ll tell you anything. Perhaps this is why Adrian sits up in the wheelhouse all day long and, apart from runs down to the galley to make coffee or bacon sandwiches, talks shit. He’s got nothing to look at but the sea and a shitty television screen that sometimes gets a couple of terrestrial channels—if we come within a hundred kilometers of land. He sits there with chronic red eyes, shifting around in the swivel chair in the same t-shirt he’s been wearing since the trip began. The trawler skippers all chat to each other via CB radio. They speak like they’ve just come out of yearlong comas.“Three of the boys I just spoke to are jacking it in,” says Adrian. “The way that the quota system is arranged, it’s impossible to make money from fishing anymore. It would make you depressed, maybe, but it takes an awful lot to make me depressed. I was thinking of moving to Alaska anyway. Go fish king crabs. I heard a boy went up there and bought a house after one summer. That’s some money!” He pauses to call and check on a few bets on his satellite phone. “I put money on a couple of horses this afternoon,” he says.Adrian keeps all the porn on the boat in his wheelhouse. It’s tame stuff—English-college-students-and-Page-3-girls shit. The Egyptian boys get a bit embarrassed whenever they see the magazines. They’ve got their own pictures of girls on their phones but they get off on headshots alone. They don’t need Adrian’s big-jug specials.

There are two bunkrooms on the boat with four beds in each. They’re blacked out and right next to the engine room so after a day or two of steaming at sea, they’re warm and smelly like saunas. At the end of a shift, you stumble into one and flop wherever you can and hope there isn’t an Egyptian already lying beneath you. There’s no shower and the crew never bothers to change their jocks or socks because everything already stinks of fish. You smoke in bed, you snore loudly, and when you need to pull one off, you do—regardless of whoever’s beneath or above you. The boat is rolling and squeaking enough already, so you probably won’t get caught.The crew were observing Ramadan during our time with them. They set alarms all over the boat so they could wake up and say prayers five times a day, individually. That’s six Egyptians with five alarms each, coupled with the skipper’s alarm to let us know when it was time to haul the nets in. After eight in the evening, we’d all sit down to a feast of the fish that the quotas forbade us from keeping. Sharks, crabs, haddock, black sole, cod, all grilled and boiled and tossed onto plates made out of newspaper. Then we’d all get stoned and listen to Egyptian dance music in a kitchen that was just about small enough to be able to touch both walls when you stretched your arms out. That was the only time the Egyptians ate. Apart from that they went around starving, just munching on cigarettes.Most boats in Ireland are crewed by foreigners. Irishmen won’t work this hard for that kind of money. The crews are Filipino, Egyptian, or Russian. All the skippers want Russians because they’re the sort of meatheads who’d lose a finger, stick it back on with fishing net, and keep on gutting. The Egyptians are a bit softer. Once, one of the crew had to be airlifted off the boat when the anchor winch swung loose and caught him in the ear. He passed out. “You have to more than pass out to get out of work on the boats,” says Adrian. “He was only acting up to go home—and he cost me 1,500 euros for the airlift.” He pauses. “But it can be dangerous sometimes, yeah. Lads lose arms. I heard of a guy who got pulled in two by the net cable. He died, so he did.”After a few days at sea you fall into a rhythm. You remember to stand with the roll of the wave so you don’t smack your head on every doorway. Whenever your hands are free for a second you get your tobacco out and roll a cigarette for later. And if you think you’re going to have more than half an hour to yourself, you head down to a bunk and get some rest.According to the British Secret Service, sleep deprivation is the most effective means of torture there is. Keep anyone awake long enough, until their skin is peeling and their nails are chewed away, and they’ll tell you anything. Perhaps this is why Adrian sits up in the wheelhouse all day long and, apart from runs down to the galley to make coffee or bacon sandwiches, talks shit. He’s got nothing to look at but the sea and a shitty television screen that sometimes gets a couple of terrestrial channels—if we come within a hundred kilometers of land. He sits there with chronic red eyes, shifting around in the swivel chair in the same t-shirt he’s been wearing since the trip began. The trawler skippers all chat to each other via CB radio. They speak like they’ve just come out of yearlong comas.“Three of the boys I just spoke to are jacking it in,” says Adrian. “The way that the quota system is arranged, it’s impossible to make money from fishing anymore. It would make you depressed, maybe, but it takes an awful lot to make me depressed. I was thinking of moving to Alaska anyway. Go fish king crabs. I heard a boy went up there and bought a house after one summer. That’s some money!” He pauses to call and check on a few bets on his satellite phone. “I put money on a couple of horses this afternoon,” he says.Adrian keeps all the porn on the boat in his wheelhouse. It’s tame stuff—English-college-students-and-Page-3-girls shit. The Egyptian boys get a bit embarrassed whenever they see the magazines. They’ve got their own pictures of girls on their phones but they get off on headshots alone. They don’t need Adrian’s big-jug specials. “Some guys go out on the boats for a month,” says Adrian. “You would go a wee bit crazy, yeah you would. Boys get back on land and get a feed of pints into them and go a wee bit mad, so they do.” Adrian’s not mad, but given a few more years he might be talking to the seagulls. At sea you spend as much time with them as you do with other humans. They live easy, these birds. The gulls always seem to know which boat is going to be hauling and when they can get a free feed. So do the dolphins and the porpoises. They all come dragging themselves behind us like starving kids chasing an ice-cream van.Boats are superstitious old things. You should never paint one green, since it’s the color of land, and you should never say the word “pig” at sea because pigs can’t swim—if they ever try, they end up slitting their own throat with their hooves. But look at this: TheArgo K’s deck is painted boldly in green. So is the roof of the galley. And Adrian refers to bacon sandwiches as pig rolls. So is theArgo Kan accident waiting to happen or are the old legends of fishermen fading away?The high point of a fishing trip is the halfway mark because then you can start talking about the things you miss on land without torturing yourself. You know you’re over the hump and will be heading back sooner than later. You can talk about women and know that in just a few days you’ll be in their company again. But Adrian’s more about the drink. He sees a beer advert on the small TV screen upstairs and jumps out of his seat to pretend to grab it.Pulling into harbor at the end of a fishing trip is like no other feeling. You’re shell-shocked. You smell like you’ve been rolling round in dead bodies for a week. It takes a while to get your land legs back again, and then you do and two pints later they’re gone again. The Egyptian boys don’t drink, so they go home and sleep for a day and a night and a day and then call their bits of Irish rough for some loving. Steve the photographer and I head back to Dublin City and start drinking. We drink everything in the house, knocking back vinegar and floor cleaner when the wine runs dry. We get refused from a bar and piss all over their doorway. We ask the deli girls with facial hair what time they clock off at. We’d have brought homeless girls home with us if we’d found them. We hop on a bin truck until we get pulled off by the bin men. We carry on till the next morning and then collapse and don’t get up again for two days. Adrian, meanwhile, drives back to Donegal. It takes him about two and a half hours, doubling the speed limit most of the way. When he gets back home, he says hi to his mum, changes his t-shirt, and heads out for the evening to ram police cars and dream of being out at sea again.

“Some guys go out on the boats for a month,” says Adrian. “You would go a wee bit crazy, yeah you would. Boys get back on land and get a feed of pints into them and go a wee bit mad, so they do.” Adrian’s not mad, but given a few more years he might be talking to the seagulls. At sea you spend as much time with them as you do with other humans. They live easy, these birds. The gulls always seem to know which boat is going to be hauling and when they can get a free feed. So do the dolphins and the porpoises. They all come dragging themselves behind us like starving kids chasing an ice-cream van.Boats are superstitious old things. You should never paint one green, since it’s the color of land, and you should never say the word “pig” at sea because pigs can’t swim—if they ever try, they end up slitting their own throat with their hooves. But look at this: TheArgo K’s deck is painted boldly in green. So is the roof of the galley. And Adrian refers to bacon sandwiches as pig rolls. So is theArgo Kan accident waiting to happen or are the old legends of fishermen fading away?The high point of a fishing trip is the halfway mark because then you can start talking about the things you miss on land without torturing yourself. You know you’re over the hump and will be heading back sooner than later. You can talk about women and know that in just a few days you’ll be in their company again. But Adrian’s more about the drink. He sees a beer advert on the small TV screen upstairs and jumps out of his seat to pretend to grab it.Pulling into harbor at the end of a fishing trip is like no other feeling. You’re shell-shocked. You smell like you’ve been rolling round in dead bodies for a week. It takes a while to get your land legs back again, and then you do and two pints later they’re gone again. The Egyptian boys don’t drink, so they go home and sleep for a day and a night and a day and then call their bits of Irish rough for some loving. Steve the photographer and I head back to Dublin City and start drinking. We drink everything in the house, knocking back vinegar and floor cleaner when the wine runs dry. We get refused from a bar and piss all over their doorway. We ask the deli girls with facial hair what time they clock off at. We’d have brought homeless girls home with us if we’d found them. We hop on a bin truck until we get pulled off by the bin men. We carry on till the next morning and then collapse and don’t get up again for two days. Adrian, meanwhile, drives back to Donegal. It takes him about two and a half hours, doubling the speed limit most of the way. When he gets back home, he says hi to his mum, changes his t-shirt, and heads out for the evening to ram police cars and dream of being out at sea again.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement