As a face-washing bowl,

And offered me a skin

As a covering cloth.

You have given me a great tongue

So that I may speak to the world.

The brave offered me fresh blood

As face-washing water,

And gave me a tail

As a hut-sweeping broom,

And offered me a thighbone

To use as a toothpick.

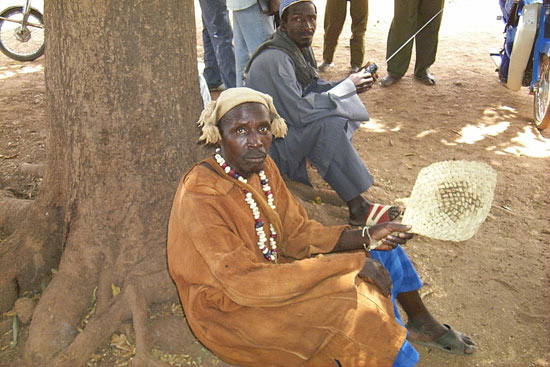

It is the hunter who has done this for me A Malian friend whose father was a donso told me a possibly apocryphal story: If one is dancing during a performance of the hunters who is not supposed to be dancing, he or she runs the risk of being killed by medicaments. It seemed like a good idea to let the guy eat the chicken carcass.