May the shopping carts of LA roll on in their victory parade.While it didn't get much attention in the mainstream press last year, a court's decision that police don't have a right to throw away people's possessions (a ruling that the Supreme Court let stand) was a huge win in a 30-year standoff between homeless and pro-gentrification policing in LA's Skid Row. Thanks to the work of local activist groups like the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD), a performance group now having a big retrospective at the Queens Museum in New York, the City of Angels is having a hard time flushing the homeless out.

Advertisement

LAPD’s a local theater group whose projects almost always come with a political agenda. It collaborates with low-income communities on everything from plays on prison psychology to Skid Row versions of Fluxus happenings. On Friday at the Queens Museum, I found several members of the Queens-based group Drogadictos Anónimos speaking like high-level bureaucrats. They were reading lines from the Spanish translation of the LAPD play "Agents & Assets," a word-for-word transcript of a 1998 hearing from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence; the committee discusses allegations by investigative reporter Gary Webb implicating the CIA in the crack epidemic of the eighties. It’s a dense script, full of legalities, political niceties, and verbiage like “the report is littered with damaging admissions."

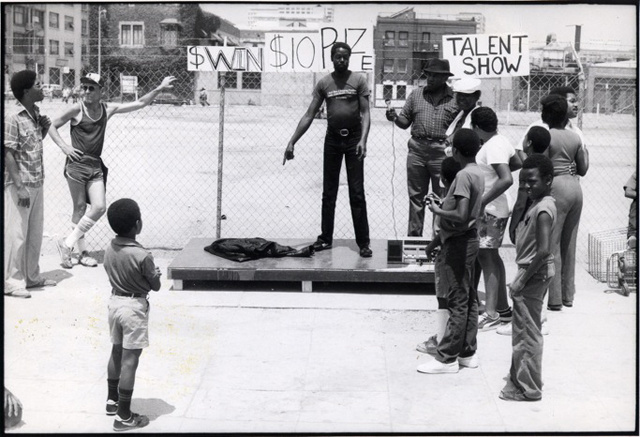

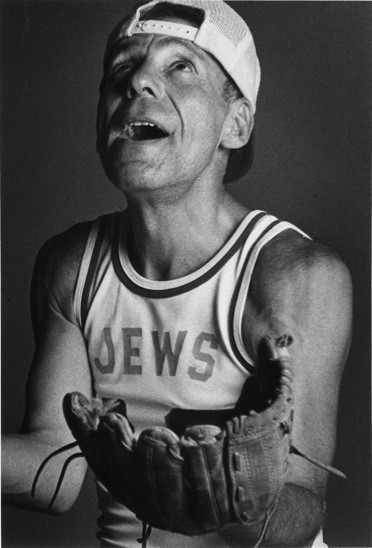

“Talent Show,” 1985 (Image courtesy of the LAPD)“This is insane text,” said Henriëtte Brouwers, LAPD's co-director and the wife of John Malpede, the group's founding artistic director. "But once people can speak the political language, it gives them a lot of confidence, whereas before they might have heard this [political jargon] and changed the channel. Now they are owning that language.” (So they are: A 17-year-old DA member immediately summed up the text for me, say that it's "because the government is supposed to be working for us, and it's not.")“A lot of drug addicts think that addiction is their problem, or that it makes them a bad person,” said Henriëtte. “Just opening up the notion that, well, there was hardly any cocaine before 1985—and putting that in a bigger history of foreign policies and illegal foreign policies and covert wars—damn, that actually has something to do with me being addicted. That’s huge.”

Advertisement

Henriëtte went on to tell me about Skid Row and LAPD’s history, from the crack epidemic of the 80s up through this summer’s Supreme Court victory. Her recollections are below.Henriëtte: [My husband] John Malpede started LAPD in 1985… That's really when homelessness came into the public view. Because, before the early 80s, you had “vagabonds” or “bums," but “homelessness” didn't exist; the word hadn't been invented, really. In the 80s Reagan started to change housing policy, taking away funding support for low-income housing and diminishing the amount of affordable housing. And as governor of California he'd closed a lot of mental-health institutions, so people with mental problems came out into the streets in California. In the 80s that policy was extended nationwide. And during the Reagan administration, people receiving disability benefits were required to re-certify to continue receiving benefits, and this proved to be impossible for many mentally disabled people. These people ended up on the streets. And then the crack epidemic happened. So all of the sudden there were thousands of homeless people. So he became interested in that; how did that happen?Basically, John was a New York performance artist from Columbia University. He likes to say, “I got tired of wearing black clothes and hanging out all night." He wanted to be a part of what was happening in society.

VICE: And so this version of Skid Row really started in the eighties.

Advertisement

Yeah, that's another history. Skid Row was full of flop houses, in disrepair, full of temporary workers. The train station used to be there, so hotels were filled with people who were working in the terminals and the wholesale fish and vegetable distribution and the warehouses nearby.There was really a transient population of workers, mostly poor white people, many addicted to alcohol. There where also native Americans and Latinos. And then in the 80s, with the crack epidemic, the homeless population took over; it was predominantly African American, with huge crack addiction problems. It was just wild, really wild and dangerous. The dope was sold out of the hotels, and people were thrown out of the windows if they didn't pay. There were big bonfires.They said they were going to clean it out and make it a new area. And that's when people who had started to change the situation on Skid Row, like the Catholic Worker Movement, said, yes, we have all these hotels, they are in terrible shape, but let's clean them up and have affordable housing for people who are poor. Luckily, at the time, Mayor Bradley was very progressive, and it was just sort of magic that he accepted that plan. So instead of knocking it down, they preserved affordable housing in all the empty banks and hotels.Now in Skid Row there are more than 50 of those SROs (single-room-occupancy hotels) where people live in very small rooms, but they are safe and clean. In the Bowery places like Whole Foods have taken over the neighborhood, but that never happened in LA. There is a real community of poor people who look out for each other, who take care of each other; all the recovery programs are there.

Advertisement

Often people see photos of people on the street, and it's like, "Oh, there's all these homeless people everywhere, how terrible." What people don't know is that many [homeless] get off the street and move into those hotels. There are people who've been living in Skid Row—many people in LAPD—for 15 or 20 years already. They cannot move out because there's no affordable housing left anywhere else.But it really has gentrified since 2002, and because it’s very desirable real estate, you have to fight for it every ten years or so. More recently, mayor Villaraigossa invited New York's police commissioner, William Bratton, to come to LA and made him our police chief. He started the "Safer Cities" initiative, with the goal of cleaning up Skid Row and making it safe for developers. So in a small area of about 50 or so blocks, Bratton put in 50 extra policemen, and they started enforcing laws that were not enforced anywhere else in Los Angeles. Jaywalking, sitting on milk crates… homeless people can’t pay the fine, so the next time they get a ticket, the [police] come back with a warrant and they go to jail.[New Yorkers will remember this from when Bratton was New York police commissioner during the Giuliani years; it’s part of his broken-windows policing tactics, which also includes Stop-and-Frisk. Bill de Blasio recently reinstated him as police commissioner.]Henriëtte: So you’re criminalizing poor people.

Advertisement

[She points to a video of LAPD's performance "Utopia/Dystopia," featuring herself and Lorinda Hawkins dueling with vacuum cleaners.]Henriëtte: The script comes from a City Council meeting on law 41.18(d), which made sitting, sleeping, or standing for long periods of time in the same spot illegal. Jan Perry, the City Council person for Skid Row, wanted to enforce that law, and the ACLU fought against it. She managed to put it on hold for a whole year so the city could keep arresting people.Finally, they came to an agreement that the law could only be enforced from from 9pm till 6 o’clock in the morning; then people could sleep. At six o’clock they came with a big water cannon, and after that, they could arrest anybody they wanted who was sleeping on the street. They came by with big garbage trucks [to throw people’s shopping carts and belongings away].[She gestures to a red shopping cart with a plaque on it.]

Henriëtte: People were arrested for stealing shopping carts and sitting on milk crates. So the Catholic Worker had a lawyer design this plaque saying that the homeless own these carts; now L.A. is full of these red carts with the plaques on them. But the police still tell people that their carts can’t be in the same place for more than two hours, and they throw it in the garbage trucks with all your possessions. So [Catholic Worker] fought it in court, and they won; this summer it went all the way up to the Supreme Court, which refused to consider the case (when the city repealed it) so that the lower court's decision stood. Now the police cannot throw peoples possessions away. And the city is forced to notify the people in advance when they are going to clean the streets.

Advertisement

[She’s standing in front of a local newspaper with the headline: "THE GREAT SHOPPING CART VICTORY PARADE."]And then of course the cops find all kinds of ways around that. When the city lost the lawsuit, the police, the BID (Business Improvement District), and the City Department of Sanitation just didn't clean up the streets anymore, and so the piles of possessions and garbage grew higher and higher. Then the police said there was a safety hazard and tried again to repeal the decision. After they lost that case, they said that there was a TB epidemic about to break out, which turned out not to be the case. It's always a new fight.The exhibit Do You Want the Cosmetic Version or the Real Deal? Los Angeles Poverty Department 1985–2014 will be on view through May 11, 2014, at the Queens Museum. The LAPD's Agents & Assets will be performed on February 28, March 1, and March 2 throughout NYC.Whitney Kimball is an NYC-based art critic currently on staff at the blog Art F City.

LAPD Group Photo

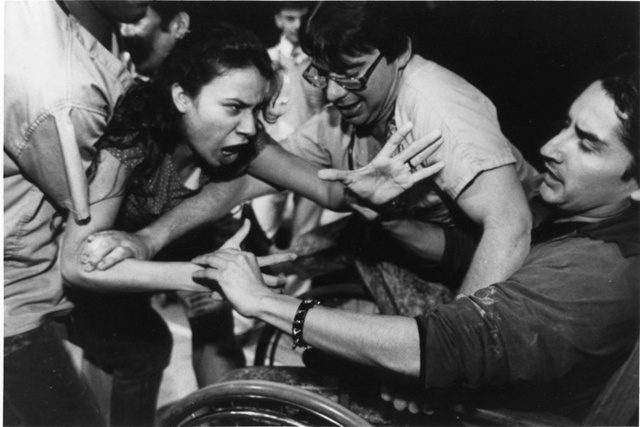

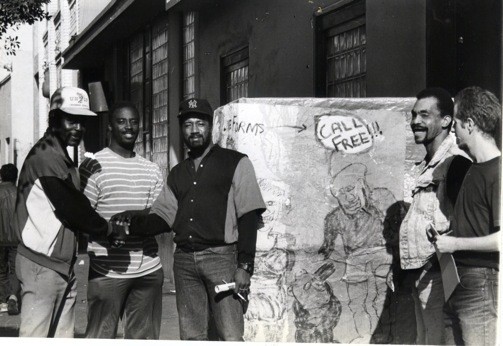

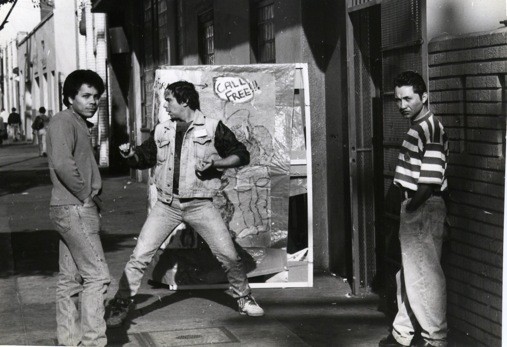

LAPD inspects Chicago, 1989

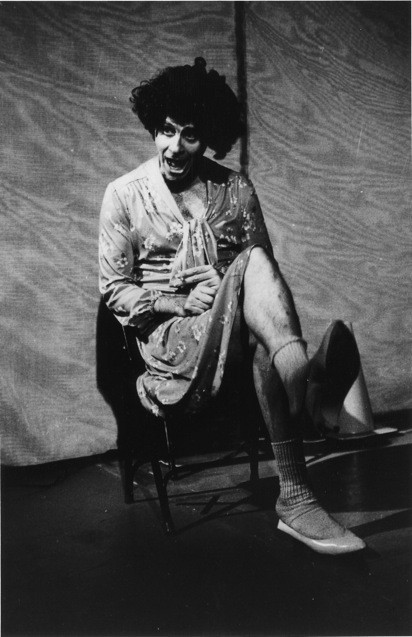

"Jupiter 35", 1989

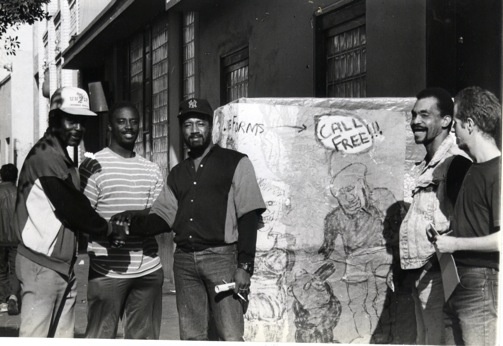

LAPD inspects San Francisco - The Robert Chapter, 1988

Talent Show, Skid Row 1985

Installation view from the Queens Museum

Installation view from the Queens Museum

Installation view from the Queens Museum

Installation view from the Queens Museum