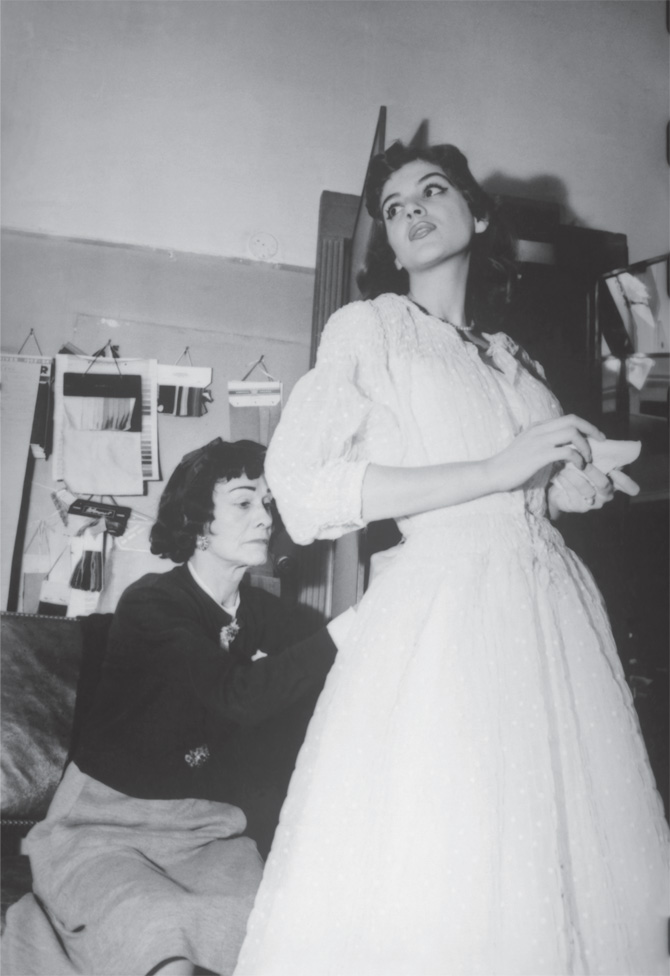

Special thanks to Danniel Rangel and Ana Sette. Vera Valdez left Brazil as a teenager and began a career in Paris in the 1950s as a model for surrealist designer Elsa Schiaparelli. By the middle of what is one of the most important decades in the history of fashion, she was traveling the world presenting Christian Dior, and eventually serving as the favorite model of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, who had just returned to postwar France to resume designing her line. Vera sat for Helmut Newton, Richard Avedon, Willy Rizzo, and Frank Horvat and had sex with many famous and marvelous people, including filmmaker Louis Malle, who, along with director Bernardo Bertolucci, helped her flee Brazil after she was sent to prison on drug charges and tortured during the military dictatorship of the mid- to late 60s. In Paris just after the war, though, Vera reigned over the nightlife scene, smoking opium with Jean Cocteau, forging a deep friendship with French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, and loving on everyone from a millionaire baron to actor Maurice Ronet. As the figurehead of the legendary Les Blouson Chanel gang—a pack of roving Chanel models—she flittered amid the celebrity social circuit looking pretty, raising spirits, and doing everyone’s drugs. She was famous and posing naked for magazines before famous people knew they were supposed to do shit like that, and later she tinkered in drug dealing and worked as a bootlegger. Today she is 75, one of Brazil’s finest stage actors, and is among the most spry and charming people we’ve ever talked to. Vice: You were very young when you first left Brazil, right?

Vera Barreto Leite Valdez: I went to study in Europe because I flunked out—I think it was the first or second year of secondary school. Were you some kind of rebel youth?

I didn’t think I was rebellious. I thought I was a little prude, although I was smoking weed at age 12. There was this friend of mine who was a little devil. We sat in the back of the class, and we smoked weed there. Back in the day there was no way a teacher would know what marijuana smelled like. You fell in with the fun, bad kids.

It was then that my dad told me he was going to send me to Europe. I was already living with my mother, who was divorced when I was four. She was a total bohemian and my dad wasn’t. He sent me to live with my Portuguese family—my grandmother and two aunts. I was there for about two years. My mom moved us to Bordeaux and from there we went to Paris, where she worked at the Brazilian Embassy. Did you start modeling immediately?

Someone asked me if I was a model, but I spoke horrible French back then. My mother told me, “I’ll explain later.” When she showed me in a magazine what a model really was, I marveled. I said, “I want that.” I remember my mom asked, “But don’t you want to go to Sorbonne a bit, maybe learn some dead language?” [laughs] I said, “No, I want to be a model.” I was eventually taken to Elsa Schiaparelli. The surrealist designer? Your mother agreed? You were barely even a teenager.

She thought I wouldn’t be accepted, so she agreed. Later she confessed, “You, such a skinny thing…” What did you do with Schiaparelli?

I did Schiaparelli’s last collection. She was a fantastic seamstress. I used to leave her studio in a costume—she’d lend me clothes. Were there other girls as well?

It was me, Brigitte Bardot, who was a photo model, and another lady called Victoire. There wasn’t such a thing as a young model at the time—especially daughters of people working at the embassies.

Advertisement

Yes. Then after Schiaparelli closed, a colleague told me, “I’m going to take you to Dior.” This was right around the launch of Dior’s famous New Look collection, right? It is considered a revolutionary time in fashion.

After Schiaparelli I didn’t think it was all that different. Dior was very much fashion. Schiaparelli wasn’t fashion—she was more like art. Dior was a factory, you know? It was another perspective. I had to punch the clock. Why did you leave Dior?

The model Suzy Parker convinced me. She said, “This woman Coco Chanel is extraordinary,” and told me Chanel’s history. And I thought, “Hmm, I don’t think my mom is going to like the idea of me working with her.” But I went there and I met this figure. I’ll never forget: I was wearing a red coat that I had bought in a boutique in Saint Germain. I remember she told Suzy: “In spite of this red coat, I want to keep her.” From there on she always had a red tailleur in her collections. She copied the prêt-à-porter. Did you two have a good relationship?

I was very young, and she was an elderly lady. Right, she had stopped designing and left Paris during the war—she had only recently returned. You didn’t get along well?

Sometimes when I was naughty she would put me in time-out. “You stay there, your back to us, facing the wall.” I loved that because I could hear the gossip. She would get angry when I hung out with “that crowd,” which was the journalists. She sounds ageist.

She’d fire me every time I’d do something wrong or when someone complained about me. It was great because I earned good money, and then a week later she would ask, “Where’s Vera? Find her!” And then I would go back and raise my fee. The accountants couldn’t believe it—I wasn’t legal. Chanel thought I was very chic. She’d say, “How do you also want her to do her papers? She has to wake up early, poor girl. She went there twice and stood in line for hours!” She liked that I was rebellious. When did you leave Chanel?

I think the last show I did for her was in ’71. Was that the last show before she died?

It was. Just before that I was in Brazil. I had a daughter, she was eight months old, and Chanel called me back. I remember this show well. I was in full lactation—my breasts were dripping. You returned to Brazil to have a baby?

I would always come to Brazil. Chanel and I would fight and I would go back… It was a very long, back-and-forth relationship.

What was your relationship with the photographers you worked with at the time? Willy Rizzo, Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton—some massive names.

Willy was very close. He was a photographer who loved the night, the models, fashion. He was delicious. He was just like us. Avedon was distant—he was very cruel with the models. He could leave you for hours in the same position, and you couldn’t move. He was already a star. It was very good to work with Newton. I have good pictures with him. Willy at that time was working for Paris Match, doing fashion journalism. I would hang out in that environment, with journalists and filmmakers. I was always with the intellectualized gang.

Advertisement

Yes. It was because of the leather jackets, Marlon Brando, and all those American cinema people. We would always go everywhere dressed in Chanel, all wearing classic tailleurs. We were the models among acquaintances, so they started calling us that. But that little gang was hardcore, you know? There was opium all the time. I had a real relationship with opium in Paris. First it was tea with hash cakes. I will never forget that—it was Moroccan. I worked as a model during the day and partied at night.

Did it end with opium?

In Brazil in the late 60s, during the dictatorship, that’s when we started with lysergic drugs. But during my exile in Paris, for instance, it was completely… even Chanel herself was addicted to morphine. By this time you’d already had your “sexual awakening”?

We used to leave Schiaparelli’s and stay all night long in a gin joint. I started dating [Brazilian filmmaker] Ruy Guerra, who was my first boyfriend. Ruy Guerra popped my cherry [laughs]. That was the sexual awakening, like almost any other girl. It was the boyfriend, the night, the liberated mother. Your mom was somehow involved with the start of your sex life? Did I miss something?

Guerra and I were like 20, and she would take us to the tranny houses in Pigalle. The only thing she didn’t take me to watch was explicit sex, but I didn’t have much curiosity in that. I liked strip tease—I thought it was beautiful. I thought it was funny that guys were completely amazed by it, as if for them sex was completely forbidden. There was no repression for me at home. My mom living in Paris, away from her entire family—she had the weight of that on her. What do you mean?

Her brother was a journalist and ambassador. Her dad was a judge and diplomat. My father’s father was a governor in Guinea during the colonial era. So when my mother left Brazil and went away to Europe, I think she was envisioning a lot of freedom. It’s the necessity of a divorced woman. I didn’t suffer through my childhood, because she just didn’t care. My education was always very liberated. So sex for me was also very free, normal, and healthy. What were the Pigalle strip joints to you?

Damn, it was naked women! My sexual initiation was completely free. I never had any problem, you know? I’d fuck easily. When did you meet Louis Malle?

We went to a club, during a return to Chanel in Paris in the early 60s, and I had just seen A Very Private Affair. We were sitting at the table and everyone started commenting on the movie. I said something like, “For Christ’s sake, that guy is so square!” I started talking about the movie and this guy was encouraging me to go on. Then someone kicked me under the table and said, “He’s the director of that movie!” I’ll never forget Malle’s face—he shrunk in his chair when I found out. Then we became good friends. Very good friends. It was great to be his friend—to fuck him and go out and hear all the gossip of other women who were in love with him. All the girls wanted to be actresses. Sounds fun!

This was at another time of crisis in fashion for me. I had just had a fight with the old hag Chanel, and at Guy Laroche’s apartment I told Malle, “I don’t want to play mannequin anymore. What do I do?” Malle said, “Become an actress!” Did you jump at the opportunity?

I said, “Oh, no. Everybody in my family is an actor. No.” He said, “I have a new project based on a book. You read it while I write the script. Then you can start.” So we went to a ski lodge in Gstaad and we started to make Le Feu Follet [The Fire Within]. Nice, huh? He asked, “What are you going to do?” I told him, “Oh, the costumes—I’ll dress the men and the women too.” He said, “OK, but how are we going to pay you?” How about with money!

I wasn’t legal. And during that time when French cinema was so radical, the film syndicate was ferocious. “But how are we going to pay Vera, how’s that going to work?” he’d ask. And there were also the credits to deal with. What do you mean? You couldn’t be listed on the credits because you were illegal?

I said, “Fuck the credits, I don’t care.” All the costumes were Chanel—everything was on loan and fixed in that way. I played a role, but that was only because I had selected the actors and I was crazy for the actor who played the main role, Maurice Ronet. Malle told me, “You have to have an affair with him, because he drinks like a beast. I don’t want this alcoholic missing any shooting days.” I said: “With great pleasure, of course!” [laughs]Vera at a sitting with Frank Horvat.

I didn’t like it. I love cinema—I think it’s interesting. But I wanted to learn about it, so I wanted to do many things. I selected the actors and had to play a retarded character because I forgot to choose someone for that role. It was like that. I would produce, from the steak tartare to the costumes to choosing the actress to giving my opinion on everything. But you always continued to model. Back in Brazil you posed for a nude spread for Fair Play magazine around this time.

[Brazilian cartoonist] Ziraldo called me and said, “Vera, you should pose nude. There’s only hookers here, but if you do it the other girls will follow!” I was married at the time, and my husband never forgave me. But then he photographed all my friends naked for Fair Play! He didn’t forgive my photo shoot. It was shot at [Brazilian writer] Rubem Braga’s penthouse. My copies always vanished. I wanted to show it to my friends but I could never find a copy at home. He would rip them all up. Was it something Chanel had done that brought you back to Brazil this time?

There was the fucking military coup of ’64, and my entire family was arrested. I had come back to Brazil and started the battle of getting them out. That’s when I came back to Brazil permanently. So you could get your family out of prison?

Yeah. Then I started getting involved with the theater people. In Paris I had done the two movies with Louis Malle, so when I got here I did some movies with directors from São Paulo—Ruy’s friends. You came back to Brazil but then went right back in exile. Why?

Because they caught me with cocaine! They caught me with a Chanel purse and they checked me completely. I didn’t know what was inside. It was at the airport, and it was the navy that arrested me. Then they went to check out who I was. Everybody in my family had either been arrested or exiled. They figured out who I was and I was arrested by DOI-CODI [the Brazilian intelligence and repression agency during the military government]. I was tortured. My God.

There’s this whole dark side of our dictatorship’s history. It was very violent. I think I was imprisoned for a month. After that I was in a rehabilitation center for nearly a year. I was very disturbed. I had panic attacks. I felt I was being chased all the time. How did you eventually get out of Brazil?

You had to pay a lot to leave Brazil, you know? And I didn’t have it. So Bertolucci sent a letter from Italy calling me to work with him and Malle. I got a visa and left. I left through Bahia [a Brazilian state], because back then the government couldn’t know—they didn’t have all that modern stuff. What did you do at that time in Paris?

I did another movie with Malle. But I didn’t do much. It was the heroin period. I really went for it. Some friends sold coke and we survived a little bit like that. The daily drug stuff—you buy some here, sell a bit there. But eventually you received amnesty and were able to return to Brazil for good. How was this homecoming?

It was hard. We were traumatized. Exile is terrible. It was tough because all our partners were very depressed and it was hard to communicate with people here. What did you do?

I got into [polemical playwright] Zé Celso. You started acting in Celso’s Teatro Oficina? How did that come about?

Well, I come from a theater family. My aunt and my mother created modernism in Brazilian theater. Zé Celso

captivated me. You can’t have anything as liberated as him. When I saw his plays in the 60s, we were living under the crazy dictatorship, the days of our destruction. So you’ve continued acting for him to this day. People say he’s fairly brutal to work with. Is it a struggle?

It is. A colossal one. He’s a monster, a genius, and a dictator director—some days he just wakes up like that. And now he’s kind of cuckoo too, so sometimes we’re in the same scene for five, six hours. But because of my age he decided to be even more powerful, very dominant, and it sometimes ends up drowning me. So we get thrashed. Outside of Brazil maybe no one knows who Zé Celso really is, but by all the other directors he’s considered one of the biggest in the world. What about fashion? Do you follow it?

No. I always saw it as work. You aren’t in least bit curious to see what a Chanel show is like nowadays?

It’s not like it used to be. It’s a circus-like spectacle. Really, all those automated things. There’s no personality anymore. So I think it’s beautiful, theatrical, but it’s indifferent, right?