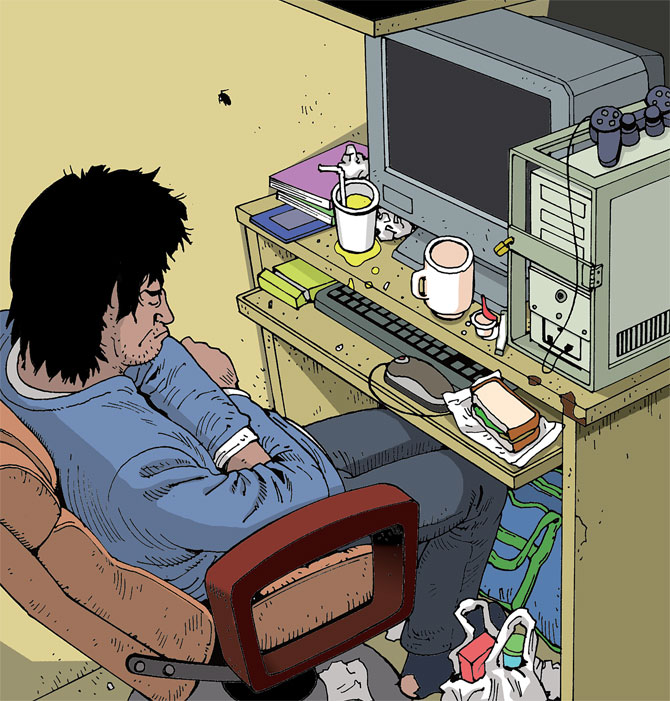

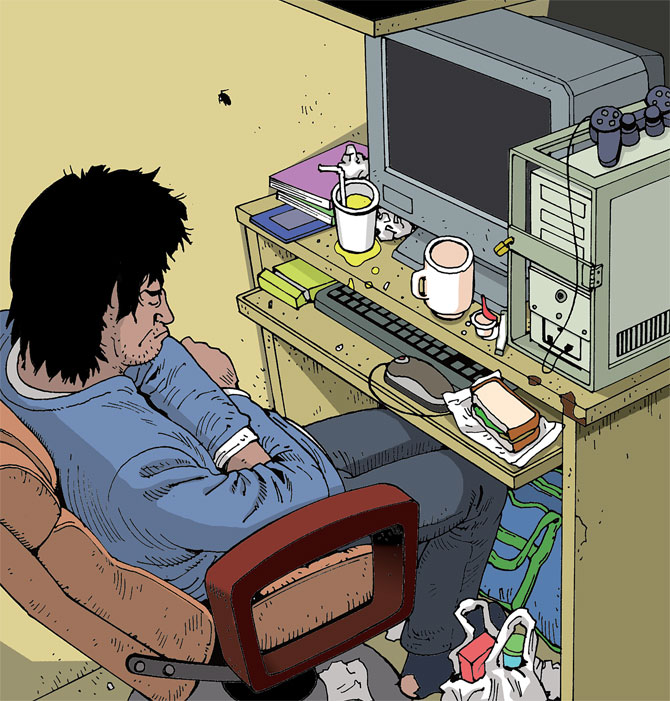

BY TOMOKAZU KOSUGA, TRANSLATED BY LENA OISHIILLUSTRATION BY SHINTARO KAGO In that age-old contest, that heroic battle of champions to decide which country has the world’s premier internet cafés, none can truly compete with Japan and its facilities. In Nippon, the web-browsing establishments are composed of personal rooms, each furnished with a computer, a TV, and a reclining chair. Snacks are sold at the checkout counter, and no matter how shitty the place is, they always have a free-soft-drinks corner. That’s right—free soda! Some of them even have showers, and all of them have well-stocked manga libraries. Most are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, so if you get sleepy while you’re doing your important internet stuff, you simply push back your reclining chair until it becomes a sort of a bed and then drift away. Before you know it, hey, that legendary Land-of-the-Rising-Sun sun is actually rising (although you won’t be seeing it from the dim confines of your drywall and plaster cave). But whatever, because you just had comfortable lodging in mega-expensive Japan for the bargain price of ¥1,000 to ¥1,500 ($10 to $15) a night. Look at that price and then reflect upon the rapidly growing number of Japanese people out of work and without a home, and you can likely guess the result: Japan’s newest breed of homeless.In fact, as the more discerning homeless have discovered the accommodations available to them for a small amount of money, the practice of finding overnight refuge in internet cafés has become a societal mainstay. According to a study conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in Tokyo and Osaka in 2007, more than 5,400 so-called internet-café refugees bed down nightly. Often they are day laborers, subsisting on cash paid at the end of each shift. The ministry cites people in their 20s as the largest percentage of this particular homeless population, at 27.7 percent, followed by people in their 50s, at 25 percent. Among the refugees in Tokyo alone, over half list “quitting work” as the reason for losing their homes. (Statistics for 2008 are not yet available, but they will undoubtedly have risen together with the surging unemployment rate.)In Tokyo, the average monthly income of these refugees is ¥107,000—about $1,140. Meanwhile, their monthly expenditures—estimating market-norm prices of ¥28,000 for accommodation, ¥26,000 for amenities, ¥29,000 for food, and additional necessities such as mobile phones—average just south of ¥100,000 per month. No shock, then, that they’re not able to save up the traditional four months’ rent for a deposit on a fixed address that would then qualify them to work as a regular employee. How do you say Catch-22 in Japanese?The Internet Café Refugee Consultation Service was christened in Tokyo and Osaka following a media shitstorm that labeled these citizens “the hidden homeless.” Café-goers eligible for consultation are Tokyo residents who have been in the city for six months but who don’t have a place to live. Obviously, this exempts vast populations of poor from consultation. And, perhaps coincidentally, the consultation service’s office is in Shinjuku’s Kabukicho¯, Tokyo’s most dangerous and seductive entertainment district. To hear the government tell it, Shinjuku has the most internet cafés. Fair enough. We’ll just respectfully add that the policy reeks of quarantine and leave it at that.Prior to visiting the bureaucrats in Kabukicho¯, and before venturing off to the most famous of these cafés-turned-flophouses, I decided to have a practice run at a lesser-known internet café in the same area. In preparation, I went days without shaving, fixing my hair, or even swapping out my sweaty t-shirt. Simple, right? Become one of them, live like they live, and obtain real-life experiences to put into my story. But upon arriving at the café, I was told by the staff at the front desk that the place was full and that there was a waiting list. It was a polite, if transparent, way of saying, “No way are you getting a room, you fucking homeless slob.” To my mind, this knighted me a certified internet-café refugee. What was left for me to do but mingle with my compatriots?Outside, I quickly spotted one slovenly gentlemen in his 30s who was mumbling to himself. I asked him, “Hey, do you want to go and grab some breakfast together? It’s my treat. Eating by yourself is lonely, you know?” But he just looked at me like I was a maniac and walked away. I approached a couple of other likely refugees with the same result. Was I coming off as a gay psychopath looking for a homeless man to rape and murder? Maaaaybe. All told, I lived among them for a week and never made any headway. But that makes sense since most of them are day workers, a collection of individuals that are largely outcast by Japanese society. That, combined with the fact that they are homeless—an extra-shameful condition in a country that already passes around shame like it’s the gravy bowl at Thanksgiving—makes it no wonder that these guys are loath to talk to strangers. Still, I wondered if it was my technique. Begrudgingly, I changed tactics and dressed up as a proper media reporter. Each time I approached someone I was denied before I could finish a sentence.Eventually, I made my way to the Tokyo suburb of Kamata, which has been featured prominently in media reports as a hub for internet-café refugees. I chose the café covered in the most reports, which is located in a ramshackle ten-story building a couple of minutes away from the station. A few feral, unkempt men loitered around, and sure enough, there in one corner was the snack bar and in another a vast collection of manga. Unexpectedly, there were flocks of junior high school kids who stampeded into the building at 7 PM to study. The old men waited out the kids’ time, impatiently sniffing their dirty t-shirts or just uncomfortably shifting from foot to foot near the elevator.This café provides two types of rooms: those with tatami (traditional Japanese straw mats) laid out on the floor and a TV, and those with a single chair, a desk, a computer, and no additional space. Since the tatami spaces only have one TV and no chairs, the extra space is used for sleeping and beating off, I assume. I opted instead for an “individual room,” which goes for about ¥100 per hour. Compared with the usual ¥400 hourly rates at most cafés, this explains its popularity. The rental was half of a room separated by a curtain, and like the others lacked any privacy or protection. Theft is on the rise among café refugees. There were lockers on each floor just outside the elevator, and there was a thick padlocked chain wrapped tightly around the TV and computer, both of which were in bad shape. The keyboard was missing keys and covered in an unsettling gooey film. The floor was dotted with cigarette butts and trash, and the wall was ripped to shreds. So much for Japan’s premier facilities, eh? All of this was in a space just large enough for me to squeeze in between a small desk and a reclining chair. Still, Japanese people, as a rule, find comfort in small spaces. I was no exception. Were it not for the persistent cigarette-induced hacking of my neighbor, I would have sworn I was cozy.

The café customers were mostly tan and wearing dirty construction-work uniforms. Needless to say, I never saw a female customer there. Nor, for that matter, did I see many young people (not counting the brief after-school visits by students), who according to the government’s survey make up the refugees’ largest demographic. In fact, I only saw one young person. (He didn’t want to talk to me, of course.) The customers who came to this café to sleep were divided equally between scruffy guys who appeared to be in their mid-30s and 40s and elderly men in their 50s and 60s. Had the transient kids the government based their findings on come and gone?

This brings us to the strange case of the government’s forthcoming program. For the purposes of their study, they called up every internet café in the country and asked them to cite the average number of all-night customers, and then furthermore the heavy users among them who sleep in their cafés on at least half the nights of a week. The fact that everything is based on the café owner’s memory makes the data untrustworthy, and it’s impossible to tell exactly how reliable any of the figures cited in the study are. (Oh, they also left questionnaires at 146 carefully selected internet cafés for customers to fill out, but how many of these tight-lipped, shame-burdened sad sacks do you think even glanced at those?)

Once back in Tokyo, I headed out to the seedy confines of Kabukicho¯ in search of consultants from the Internet Café Refugee Consultation Service who could help me understand the refugee problem and the government’s role in it. I walked for more than an hour during the scheduled patrol times indicated on the service’s website but had no luck.

I called their consultation desk the next morning and was told that they had canceled the patrol at 7:30 PM because of an approaching typhoon. I remarked that there had been no rain at all yesterday and was told, “It was probably determined by the staff that was on-site last night. This patrol is indeed an outreach program to find and talk to potential internet-café refugees, but rather than walking around to find us on patrol, I think you’d be better off making a reservation by phone for a consultation session at our office.” OK, so what’s the point of announcing the patrol on their website if they don’t want people looking for them? “Well, not everybody checks our homepage regularly, you know?” Right. These refugees, who by the government’s own findings are supposed to be young and consumed with the internet, are living at an internet café but not using the internet to track down free money. Makes perfect sense that they’d pick up the phone instead, right?

This kind of system-wide incompetence led to the government’s new loan system, which is set to begin during fiscal year 2009. The system offers ¥150,000 per month for accommodation and living expenses for a period of three to six months, on the condition that the receiver attends training at a local Public Employment Security Office. Since trainees with an annual income of less than ¥1.5 million are exempt from repaying the loan, you could say that it’s essentially a benefit package. So, you know, great for them! The government will be dedicating ¥100 million to this incentive. However, only dispatch workers in their mid-30s or younger who regularly sleep in internet cafés are eligible. In other words, the middle-aged and elderly working poor are not covered. And there’s another catch: Since it will cost an average of around ¥700,000 to support one refugee, that would only add up to a total of 200 or so refugees actually benefiting from the ¥100 million budget. That’s only about 27 percent of the 5,400 refugees that the government found in their study—from 2007. I know I just threw a lot of numbers at you there, so let’s say it another way: The Japanese government is trying to put out a raging fire with an eyedropper full of spit, and a lot of homeless Japanese senior laborers are going to spend a lot of time on the internet in 2009.

In that age-old contest, that heroic battle of champions to decide which country has the world’s premier internet cafés, none can truly compete with Japan and its facilities. In Nippon, the web-browsing establishments are composed of personal rooms, each furnished with a computer, a TV, and a reclining chair. Snacks are sold at the checkout counter, and no matter how shitty the place is, they always have a free-soft-drinks corner. That’s right—free soda! Some of them even have showers, and all of them have well-stocked manga libraries. Most are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, so if you get sleepy while you’re doing your important internet stuff, you simply push back your reclining chair until it becomes a sort of a bed and then drift away. Before you know it, hey, that legendary Land-of-the-Rising-Sun sun is actually rising (although you won’t be seeing it from the dim confines of your drywall and plaster cave). But whatever, because you just had comfortable lodging in mega-expensive Japan for the bargain price of ¥1,000 to ¥1,500 ($10 to $15) a night. Look at that price and then reflect upon the rapidly growing number of Japanese people out of work and without a home, and you can likely guess the result: Japan’s newest breed of homeless.In fact, as the more discerning homeless have discovered the accommodations available to them for a small amount of money, the practice of finding overnight refuge in internet cafés has become a societal mainstay. According to a study conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in Tokyo and Osaka in 2007, more than 5,400 so-called internet-café refugees bed down nightly. Often they are day laborers, subsisting on cash paid at the end of each shift. The ministry cites people in their 20s as the largest percentage of this particular homeless population, at 27.7 percent, followed by people in their 50s, at 25 percent. Among the refugees in Tokyo alone, over half list “quitting work” as the reason for losing their homes. (Statistics for 2008 are not yet available, but they will undoubtedly have risen together with the surging unemployment rate.)In Tokyo, the average monthly income of these refugees is ¥107,000—about $1,140. Meanwhile, their monthly expenditures—estimating market-norm prices of ¥28,000 for accommodation, ¥26,000 for amenities, ¥29,000 for food, and additional necessities such as mobile phones—average just south of ¥100,000 per month. No shock, then, that they’re not able to save up the traditional four months’ rent for a deposit on a fixed address that would then qualify them to work as a regular employee. How do you say Catch-22 in Japanese?The Internet Café Refugee Consultation Service was christened in Tokyo and Osaka following a media shitstorm that labeled these citizens “the hidden homeless.” Café-goers eligible for consultation are Tokyo residents who have been in the city for six months but who don’t have a place to live. Obviously, this exempts vast populations of poor from consultation. And, perhaps coincidentally, the consultation service’s office is in Shinjuku’s Kabukicho¯, Tokyo’s most dangerous and seductive entertainment district. To hear the government tell it, Shinjuku has the most internet cafés. Fair enough. We’ll just respectfully add that the policy reeks of quarantine and leave it at that.Prior to visiting the bureaucrats in Kabukicho¯, and before venturing off to the most famous of these cafés-turned-flophouses, I decided to have a practice run at a lesser-known internet café in the same area. In preparation, I went days without shaving, fixing my hair, or even swapping out my sweaty t-shirt. Simple, right? Become one of them, live like they live, and obtain real-life experiences to put into my story. But upon arriving at the café, I was told by the staff at the front desk that the place was full and that there was a waiting list. It was a polite, if transparent, way of saying, “No way are you getting a room, you fucking homeless slob.” To my mind, this knighted me a certified internet-café refugee. What was left for me to do but mingle with my compatriots?Outside, I quickly spotted one slovenly gentlemen in his 30s who was mumbling to himself. I asked him, “Hey, do you want to go and grab some breakfast together? It’s my treat. Eating by yourself is lonely, you know?” But he just looked at me like I was a maniac and walked away. I approached a couple of other likely refugees with the same result. Was I coming off as a gay psychopath looking for a homeless man to rape and murder? Maaaaybe. All told, I lived among them for a week and never made any headway. But that makes sense since most of them are day workers, a collection of individuals that are largely outcast by Japanese society. That, combined with the fact that they are homeless—an extra-shameful condition in a country that already passes around shame like it’s the gravy bowl at Thanksgiving—makes it no wonder that these guys are loath to talk to strangers. Still, I wondered if it was my technique. Begrudgingly, I changed tactics and dressed up as a proper media reporter. Each time I approached someone I was denied before I could finish a sentence.Eventually, I made my way to the Tokyo suburb of Kamata, which has been featured prominently in media reports as a hub for internet-café refugees. I chose the café covered in the most reports, which is located in a ramshackle ten-story building a couple of minutes away from the station. A few feral, unkempt men loitered around, and sure enough, there in one corner was the snack bar and in another a vast collection of manga. Unexpectedly, there were flocks of junior high school kids who stampeded into the building at 7 PM to study. The old men waited out the kids’ time, impatiently sniffing their dirty t-shirts or just uncomfortably shifting from foot to foot near the elevator.This café provides two types of rooms: those with tatami (traditional Japanese straw mats) laid out on the floor and a TV, and those with a single chair, a desk, a computer, and no additional space. Since the tatami spaces only have one TV and no chairs, the extra space is used for sleeping and beating off, I assume. I opted instead for an “individual room,” which goes for about ¥100 per hour. Compared with the usual ¥400 hourly rates at most cafés, this explains its popularity. The rental was half of a room separated by a curtain, and like the others lacked any privacy or protection. Theft is on the rise among café refugees. There were lockers on each floor just outside the elevator, and there was a thick padlocked chain wrapped tightly around the TV and computer, both of which were in bad shape. The keyboard was missing keys and covered in an unsettling gooey film. The floor was dotted with cigarette butts and trash, and the wall was ripped to shreds. So much for Japan’s premier facilities, eh? All of this was in a space just large enough for me to squeeze in between a small desk and a reclining chair. Still, Japanese people, as a rule, find comfort in small spaces. I was no exception. Were it not for the persistent cigarette-induced hacking of my neighbor, I would have sworn I was cozy.

The café customers were mostly tan and wearing dirty construction-work uniforms. Needless to say, I never saw a female customer there. Nor, for that matter, did I see many young people (not counting the brief after-school visits by students), who according to the government’s survey make up the refugees’ largest demographic. In fact, I only saw one young person. (He didn’t want to talk to me, of course.) The customers who came to this café to sleep were divided equally between scruffy guys who appeared to be in their mid-30s and 40s and elderly men in their 50s and 60s. Had the transient kids the government based their findings on come and gone?

This brings us to the strange case of the government’s forthcoming program. For the purposes of their study, they called up every internet café in the country and asked them to cite the average number of all-night customers, and then furthermore the heavy users among them who sleep in their cafés on at least half the nights of a week. The fact that everything is based on the café owner’s memory makes the data untrustworthy, and it’s impossible to tell exactly how reliable any of the figures cited in the study are. (Oh, they also left questionnaires at 146 carefully selected internet cafés for customers to fill out, but how many of these tight-lipped, shame-burdened sad sacks do you think even glanced at those?)

Once back in Tokyo, I headed out to the seedy confines of Kabukicho¯ in search of consultants from the Internet Café Refugee Consultation Service who could help me understand the refugee problem and the government’s role in it. I walked for more than an hour during the scheduled patrol times indicated on the service’s website but had no luck.

I called their consultation desk the next morning and was told that they had canceled the patrol at 7:30 PM because of an approaching typhoon. I remarked that there had been no rain at all yesterday and was told, “It was probably determined by the staff that was on-site last night. This patrol is indeed an outreach program to find and talk to potential internet-café refugees, but rather than walking around to find us on patrol, I think you’d be better off making a reservation by phone for a consultation session at our office.” OK, so what’s the point of announcing the patrol on their website if they don’t want people looking for them? “Well, not everybody checks our homepage regularly, you know?” Right. These refugees, who by the government’s own findings are supposed to be young and consumed with the internet, are living at an internet café but not using the internet to track down free money. Makes perfect sense that they’d pick up the phone instead, right?

This kind of system-wide incompetence led to the government’s new loan system, which is set to begin during fiscal year 2009. The system offers ¥150,000 per month for accommodation and living expenses for a period of three to six months, on the condition that the receiver attends training at a local Public Employment Security Office. Since trainees with an annual income of less than ¥1.5 million are exempt from repaying the loan, you could say that it’s essentially a benefit package. So, you know, great for them! The government will be dedicating ¥100 million to this incentive. However, only dispatch workers in their mid-30s or younger who regularly sleep in internet cafés are eligible. In other words, the middle-aged and elderly working poor are not covered. And there’s another catch: Since it will cost an average of around ¥700,000 to support one refugee, that would only add up to a total of 200 or so refugees actually benefiting from the ¥100 million budget. That’s only about 27 percent of the 5,400 refugees that the government found in their study—from 2007. I know I just threw a lot of numbers at you there, so let’s say it another way: The Japanese government is trying to put out a raging fire with an eyedropper full of spit, and a lot of homeless Japanese senior laborers are going to spend a lot of time on the internet in 2009.

Advertisement