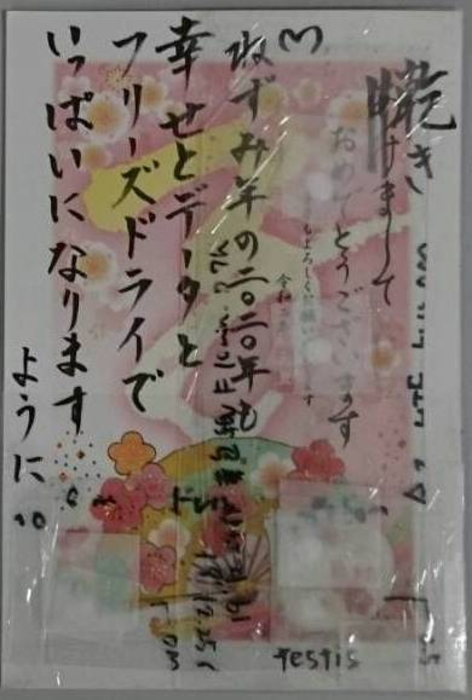

A mouse produced by the postcard sperm sits next to a letter. Image: Daiyu I

ABSTRACT breaks down mind-bending scientific research, future tech, new discoveries, and major breakthroughs.

Advertisement

Mouse pups born from sperm sent on the postcards. Image: Daiyu Ito, University of Yamanashi

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement