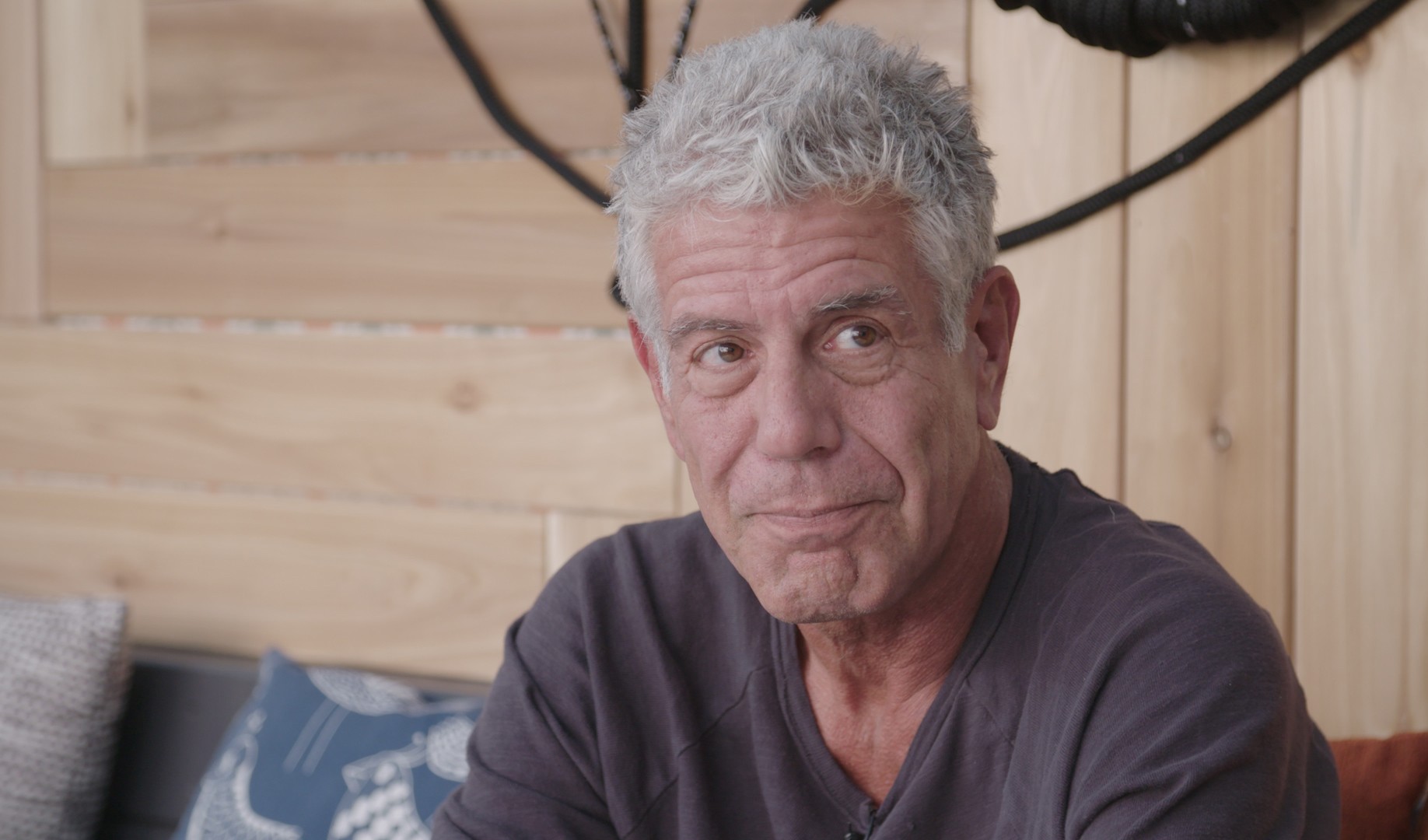

We at MUNCHIES are devastated by the death of Anthony Bourdain, one of our friends and heroes. In his memory, we're running a series of essays about the ways he changed our lives. If you or someone you know is considering suicide, help is available. Call 1-800-273-8255 to speak with someone now or text START to 741741 to message with the Crisis Text Line.

All food television is a love note. It is usually tame, romantic, the food approached like a one-kneed engagement proposal—the pristine white plates, the meticulously arranged duck breast beside dainty vegetables, the crisp geometry of the tablecloths. Even Guy Fieri, the salami-wrapped nacho-cheez orgasm himself, whose shows are admittedly gluttonous and lustful, feels like a theater act, like a boy who’s found his first Playboy, holding it up horizontal and hollering TITS to everyone in range.

All food television is a love note. It is usually tame, romantic, the food approached like a one-kneed engagement proposal—the pristine white plates, the meticulously arranged duck breast beside dainty vegetables, the crisp geometry of the tablecloths. Even Guy Fieri, the salami-wrapped nacho-cheez orgasm himself, whose shows are admittedly gluttonous and lustful, feels like a theater act, like a boy who’s found his first Playboy, holding it up horizontal and hollering TITS to everyone in range.

Advertisement

Then there was Anthony Bourdain. Bourdain saw food and feasts like a moment in the backseat of a car, with something like eagerness and awe simultaneously. His relationship with them was indulgent and pornographic and he knew it, all the hypnotic stirring of sauces and the palms covered in a sheen of animal fat, a hunk of beef sawed apart with rabid fervor, leaking streams of juice all over.In the Scotland episode of Parts Unknown, Bourdain sits in a cluttered diner, narrating a montage of scenes in which all conceivable foods are dunked in batter and then deep-fried. He orders haddock, and haggis, and French fries covered in cheese and curry sauce, each item the same vague yellow. As he lifts a French fry, a bungee cord of cheese dangling from it, he says, “I’m pretty sure God is against this.” Food to him could be something forbidden and decadent and something like a warm bath all at once, and even as his shows became more anthropological, the meals remained, a grand disarmer and unifier.

Photo by Tannis Toohey/Toronto Star via Getty Images

But what made his celebrations feel so pure was this: When his code—that devout belief that food and drink exist only for the purpose of sensory elevation, not the sad dance for your Personal Brand—was violated, he would admonish with great delight. He would not hesitate. He was your ornery father on hold with customer service, mashing the keypad looking for a Real Human, emptying-the-clip-but-he’s-sort-of-got-a-point. Bourdain called well-done meat the food for “pretheatre … philistines”; brunch was for People Who Brunch; vegetarians were “enemies of everything that’s good and decent in the human spirit”. Remembering a scene at a San Francisco craft beer bar, where everywhere he looked was people tasting multiple beers from tiny cups, taking notes, he said, “This is fucking Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” About people photographing their food: “It’s bullshit. It’s about making other people feel bad about what they’re eating.”

Advertisement

He became an avatar of hedonism because in a time of performative consumption, of foods and moments, all of it felt like a genuine reflex, the curious conversations with locals, the way he seemed to be biologically and spiritually nourished, in real time like a videogame health meter filling, by a dish called clam rice on the streets in Vietnam. Describing sushi at Sukiyabashi Jiro in Tokyo, and the religious obedience of waiting to be presented with each course, he said, “You sit down, right in front of him, you look him in the eyes and pick it up and put it in your mouth.” Sometimes, listening to Bourdain, it was hard to tell whether he was talking about eating, fucking, or a visit from Christ.He went to West Virginia, he went to Armenia, he went to New Jersey when there were heaps of snow on the ground and talked about the smell of beach grass in the dunes that he could remember from when he was a child. He knew that intimacy is everywhere, in every alley and doorway, if not because he felt it everywhere then because he knew home, and the feeling of a full stomach, and that these places, microscopic and bleak as they might be, could exist as those things for other people just the same.

His shows became more cinematically daring as they went. There were cellos and accordions scoring slow-motion black and white close-ups, fluctuating with aerial shots of cityscapes to freeze-frames, first-person sequences of children racing on sidewalks. It was I LOVE ADVENTURE not as the vacant brag of a Tinder bio but as pilgrimage, the surrealism of a dream, the quick flicker of nostalgia and deep calm of a food coma.

Talking about his appreciation for red wine, for all its calibers, he said, “They're so unpredictable. I know nothing about them. It's always a surprise. Spin the wheel. Some of them suck, some of them are going to be good, some will be interesting—that's interesting to me.”Sometimes, listening to Bourdain, it was hard to tell whether he was talking about eating, fucking, or a visit from Christ.

His shows became more cinematically daring as they went. There were cellos and accordions scoring slow-motion black and white close-ups, fluctuating with aerial shots of cityscapes to freeze-frames, first-person sequences of children racing on sidewalks. It was I LOVE ADVENTURE not as the vacant brag of a Tinder bio but as pilgrimage, the surrealism of a dream, the quick flicker of nostalgia and deep calm of a food coma.

Advertisement

Here is another song he sang to a stranger.

Advertisement

“My only suggestion is to not give a fuck about what might be wanted or expected and make the most personal, best, strangest thing you can. And write natural sounding VO with a point of view that sounds like people actually talk

We made an episode, but I choked. The errors were all my fault. It was fine but it was dull; I made something that was like things I had seen before. I even went and got B-roll of the Brooklyn Bridge. We didn’t make the series. I deeply, deeply gave a fuck, was the problem.In the first scene of the episode in Buenos Aires, Bourdain is sitting on a folding chair, drinking beer from a see-through plastic cup, watching as the planes take off. One of the men watching with him says this is what they do, they wait here together in the shade, they don’t even know anyone in those planes. A full minute of this. Instead of saying this is why I’m here, he found the backstreets and the weeds and the runways and put his hands on them, and he said look at where I am.Whatever you make--make it NOT like what everybody else is doing.”