Screen shots of Mindbloom ads.

Mindbloom, and the many similar teleservices springing up, are raising questions about what psychedelic therapy should be like in practice, especially how much support and expertise should be required for such treatments and the limits of telemedicine in this nascent field. Notably, teleservices like Mindbloom, that prescribe controlled substances virtually, can only exist at all because of the loosening of regulations as a result of the pandemic. Whether these companies will represent a permanent part of psychedelic treatment's future or be blocked by legislation is yet to be determined—but it’s not a stretch to say that the safety practices of those operating today could have an impact on that outcome.Mindbloom is on a mission to transform lives by expanding patient access to safe, clinically effective, and science-backed mental healthcare therapies. Mindbloom’s platform has grown significantly since launch to meet growing demand for alternatives to traditional prescription drugs in the face of a mental health crisis. Each day, our team works tirelessly to meet our clients’ and providers’ needs, and to improve our services. We are grateful for the guidance of leaders in the fields of psychiatry and psychedelic medicine who have developed and oversee industry-leading treatment protocols, including our Medical Director Dr. Leonardo Vando, our Science Director Dr. Casey Paleos, and our world-class board of clinical advisors. We are proud of the clinical outcomes, safety record, and transformational stories we’ve accumulated across thousands of clients, exceeding those of traditional treatment options such as SSRI antidepressants. We remain committed to bringing positive change to the lives of our clients and being a supportive ally throughout their journeys.

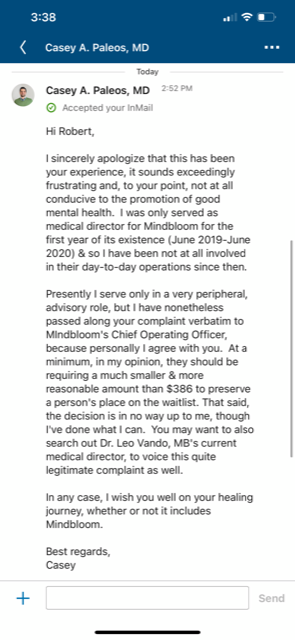

Screen shot of email from Mindbloom.