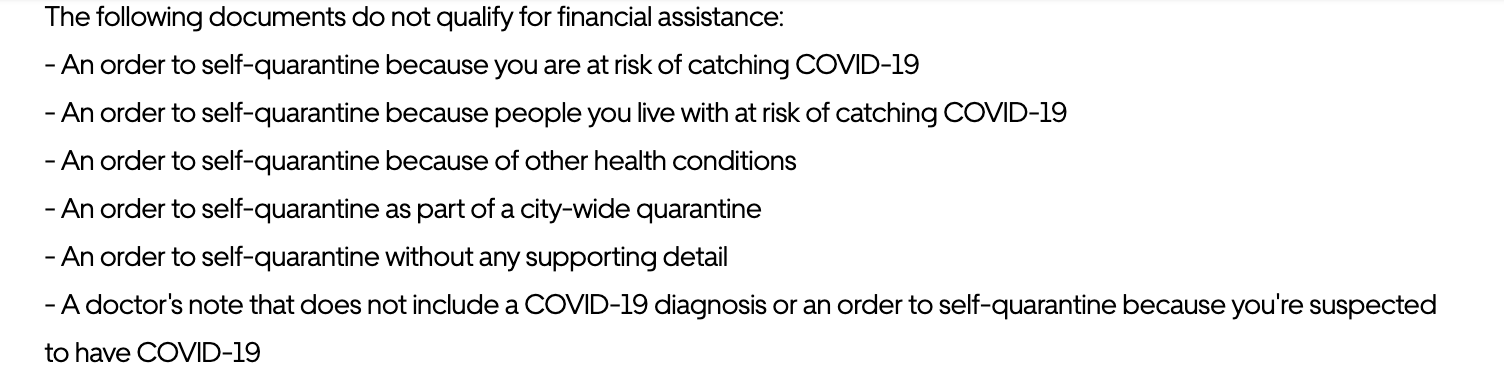

For years, Dhruv has been a full-time Uber driver in New York City who has structured his life, including his diabetes treatment, around the 60-hour workweeks he needs to make ends meet. As the coronavirus pandemic crushed the city, he felt increasingly unable to safely manage his condition while driving for Uber, pushing him to give up his main source of income and risk being unable to afford his daily medication."My diabetes means coronavirus, any virus actually, puts me at much higher risk for getting a severe case and dying just like that," Dhruv told Motherboard. "For me, the choice was to risk rationing or risk dying. Uber closed its [Greenlight Hubs] before even giving us hand sanitizer. Of course, I stopped driving right after. No masks or dividers, but we got an email wishing us luck in staying safe and making them money. If Uber thinks its offices shouldn’t stay open, then why should we?”When Uber first rolled out its sick paid leave policy on March 7th, Dhruv thought applying to it would be a waste of time, anticipating that it would be a nightmare that ultimately wouldn’t last him long. Dhruv considered applying for unemployment benefits in New York because in 2018, the state's unemployment insurance appeal board ruled three drivers—along with others who were "similarly situated"—could claim unemployment benefits. Despite that ruling, however, drivers have complained that the process is being actively sabotaged by Uber and individual claims are dragged out to last months. In the end, neither he nor any driver in his network began the sick paid leave application process and instead kept driving or self-quarantined themselves. Dhruv continued to self-quarantine, borrowed money from family members to stay afloat, and began applying for unemployment benefits. Motherboard is only using his first name because he fears reprisal from Uber.It’s understandable why Dhruv and others have not bothered applying for Uber’s sick pay program. In the month since it was introduced, the policy has changed multiple times in ways that have excluded the very groups who need sick paid leave the most while increasing the documentation required to receive compensation. Uber did not respond to Motherboard’s request for numbers about how many drivers have been infected with Covid-19 or provided with sick paid leave, but a driver lawsuit seeking an expansion of Uber’s program alleges the company has only paid 1,400 drivers out of its approximately 2 million US drivers. Uber has confirmed elsewhere that more than 1,400 drivers have been infected, with at least one death in the United States, one in Brazil, and another in London.Initially, Uber required proof of a positive test or exposure to someone who was diagnosed with coronavirus, but testing was widely unavailable unless you were significantly wealthier than an Uber driver. After pressure from driver advocacy groups like the Independent Drivers Guild, which sought expansionary changes from the ride-hailing giant and appealed individual denials of claims, Uber announced on March 15th that you might qualify for sick paid leave if “personally asked to self-isolate by a public health authority or licensed medical authority” or if your account was caught in one of Uber’s mass suspensions meant to limit outbreaks on the platform.By March 24th, Uber had backtracked on its policy changes by changing eligibility and documentation requirements. The rule promising sick paid leave if you had a doctor's note to self-isolate due to pre-existing conditions or high at-risk demographics (e.g. immunocompromised individuals and seniors) was amended to only apply if you were asked to self-isolate “due to your risk of spreading COVID-19.”Uber narrowed its eligibility requirements once again by April 1st, restricting sick paid leave to those with “written documentation” showing the driver either had COVID-19 or was suspected of having it, along with additional requirements demanding “a description of your suspected risk of having COVID-19 and spreading it to others.” Uber also updated its policy to explain what documents did not qualify: As its original April 6th deadline for claiming sick pay approached, it was becoming clear that drivers were struggling to get help, facing prolonged delays unless they told their stories on social media or to major news outlets. On Friday, Uber announced that it would be returning to its earlier policy of allowing drivers with preexisting conditions to apply for sick paid leave and would accept a doctor's note explaining a preexisting condition that put the driver at a higher risk of complications from coronavirus. Furthermore, Uber promised it would go back and review past claims it rejected and approve those from drivers with preexisting conditions.

As its original April 6th deadline for claiming sick pay approached, it was becoming clear that drivers were struggling to get help, facing prolonged delays unless they told their stories on social media or to major news outlets. On Friday, Uber announced that it would be returning to its earlier policy of allowing drivers with preexisting conditions to apply for sick paid leave and would accept a doctor's note explaining a preexisting condition that put the driver at a higher risk of complications from coronavirus. Furthermore, Uber promised it would go back and review past claims it rejected and approve those from drivers with preexisting conditions. While Uber's new policy expands coverage, it again adds new restrictions that might hurt its drivers. Uber hasn’t restored the eligibility of drivers in groups with a higher risk of serious illness (e.g. seniors) or drivers who may have come into contact with a confirmed case of coronavirus. It has also introduced a “maximum per-person payment” that puts a cap on sick paid leave. This "maximum payment" depends on the city and its average earnings but is a departure from early policies that paid out based on an individual driver's historical earnings.“We are expanding eligibility to include drivers and delivery people who have been told to individually quarantine because they have preexisting conditions that put them at a higher risk of suffering serious illness from COVID-19,” Uber wrote in a blog post explaining the changes. “Because this will mean more people are eligible than under the old policy, we’ve chosen to establish a maximum per-person payment to make this new policy more sustainable.”For some drivers, these changes aren’t enough. In New York City, Uber’s changes still don’t take into account the effect of its quota system that locked drivers out of the app and lowered earnings for many drivers. Aziz Bah, an organizer with the Independent Drivers Guild, told Motherboard that he’s helped drivers apply for sick paid leave and watched them receive as little as $200 despite spending more than 60 hours a week in their car to hit Uber’s strict quotas.“The payout was based on your weekly average earnings for the last six months, right? Well, the lockout meant some drivers only had a chance to actually get rides for two or three days, even if they spent the rest of the week driving around,” Bah told Motherboard. “Drivers feel that it's arbitrary and unfair, they know they are being shortchanged, but they also feel like they just gotta take it and be quiet because this is the little help they'll get."Ramana Prai is a London based Uber driver who the company offered £200 (~$250) in sick paid leave. Since coronavirus coverage picked up in February, he slowly reduced his driving and eventually stopped driving on March 20th. On March 22nd, he was diagnosed with coronavirus and self-isolated until April 3rd. Prai doesn't expect to see government relief grants until June, which means as the primary source of income in his household, he has two options familiar to many drivers at this point: drive to put food on the table and risk getting sick (again) or stay home and starve.“I’ve been driving for six years. Uber has taken at least £10,000 in commission from me each year! They take 20 percent of my earnings, then offer me £200,” Prai told Motherboard. “I don’t understand how they can take £60,000 from me, then offer nothing when I’m in need. How can I provide for my partner and 2 kids with this? My employer has let me down.”Uber’s new policy change that expands eligibility is a move in the right direction, but it shouldn’t be removed from the proper context. For the past month, Uber has dragged its feet on claims and narrowed eligibility criteria so severely that, by its own count, only 1,400 drivers have been paid. It has dropped some of its new requirements, imposed new ones, and reframes this shift as an attempt to keep the policy “sustainable” which suggests there will be future changes.This is the same company that has for years cut driver wages down to starvation levels, began last year to lock out drivers from its app to reverse its period of investor-subsidized exponential growth, and has weaved a path of destruction through the world’s cities by worsening pollution, traffic, public transit, and urban mobility. Sustainability means profitability, which Uber is no closer to achieving, but wants investors to continue believing despite its disastrous post-IPO performance. That means improving its balance sheet by hoarding cash during the pandemic, but also minimizing costs fighting to keep workers misclassified as contractors so the taxpayer picks up traditional employer costs like health insurance, unemployment, and disability benefits.Instead of helping its workers through this pandemic, Uber’s real coronavirus response is to try and make permanent its refusal to properly classify and compensate its app-based employees. In a desperate letter to the President, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi asked the federal government to pursue a “third category” classification for Uber drivers that would provide minimal employee benefits, while allowing the company to still treat its workers as contractors. Khosrowshahi took to Twitter to celebrate the CARES Act’s passage in the Senate, and for good reason. The pandemic offers Uber, and every other gig platform, a chance to finally write into federal law a business model that states like California and New York have been beginning to challenge.

While Uber's new policy expands coverage, it again adds new restrictions that might hurt its drivers. Uber hasn’t restored the eligibility of drivers in groups with a higher risk of serious illness (e.g. seniors) or drivers who may have come into contact with a confirmed case of coronavirus. It has also introduced a “maximum per-person payment” that puts a cap on sick paid leave. This "maximum payment" depends on the city and its average earnings but is a departure from early policies that paid out based on an individual driver's historical earnings.“We are expanding eligibility to include drivers and delivery people who have been told to individually quarantine because they have preexisting conditions that put them at a higher risk of suffering serious illness from COVID-19,” Uber wrote in a blog post explaining the changes. “Because this will mean more people are eligible than under the old policy, we’ve chosen to establish a maximum per-person payment to make this new policy more sustainable.”For some drivers, these changes aren’t enough. In New York City, Uber’s changes still don’t take into account the effect of its quota system that locked drivers out of the app and lowered earnings for many drivers. Aziz Bah, an organizer with the Independent Drivers Guild, told Motherboard that he’s helped drivers apply for sick paid leave and watched them receive as little as $200 despite spending more than 60 hours a week in their car to hit Uber’s strict quotas.“The payout was based on your weekly average earnings for the last six months, right? Well, the lockout meant some drivers only had a chance to actually get rides for two or three days, even if they spent the rest of the week driving around,” Bah told Motherboard. “Drivers feel that it's arbitrary and unfair, they know they are being shortchanged, but they also feel like they just gotta take it and be quiet because this is the little help they'll get."Ramana Prai is a London based Uber driver who the company offered £200 (~$250) in sick paid leave. Since coronavirus coverage picked up in February, he slowly reduced his driving and eventually stopped driving on March 20th. On March 22nd, he was diagnosed with coronavirus and self-isolated until April 3rd. Prai doesn't expect to see government relief grants until June, which means as the primary source of income in his household, he has two options familiar to many drivers at this point: drive to put food on the table and risk getting sick (again) or stay home and starve.“I’ve been driving for six years. Uber has taken at least £10,000 in commission from me each year! They take 20 percent of my earnings, then offer me £200,” Prai told Motherboard. “I don’t understand how they can take £60,000 from me, then offer nothing when I’m in need. How can I provide for my partner and 2 kids with this? My employer has let me down.”Uber’s new policy change that expands eligibility is a move in the right direction, but it shouldn’t be removed from the proper context. For the past month, Uber has dragged its feet on claims and narrowed eligibility criteria so severely that, by its own count, only 1,400 drivers have been paid. It has dropped some of its new requirements, imposed new ones, and reframes this shift as an attempt to keep the policy “sustainable” which suggests there will be future changes.This is the same company that has for years cut driver wages down to starvation levels, began last year to lock out drivers from its app to reverse its period of investor-subsidized exponential growth, and has weaved a path of destruction through the world’s cities by worsening pollution, traffic, public transit, and urban mobility. Sustainability means profitability, which Uber is no closer to achieving, but wants investors to continue believing despite its disastrous post-IPO performance. That means improving its balance sheet by hoarding cash during the pandemic, but also minimizing costs fighting to keep workers misclassified as contractors so the taxpayer picks up traditional employer costs like health insurance, unemployment, and disability benefits.Instead of helping its workers through this pandemic, Uber’s real coronavirus response is to try and make permanent its refusal to properly classify and compensate its app-based employees. In a desperate letter to the President, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi asked the federal government to pursue a “third category” classification for Uber drivers that would provide minimal employee benefits, while allowing the company to still treat its workers as contractors. Khosrowshahi took to Twitter to celebrate the CARES Act’s passage in the Senate, and for good reason. The pandemic offers Uber, and every other gig platform, a chance to finally write into federal law a business model that states like California and New York have been beginning to challenge.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement