Illustrations by Fredrik Söderberg [](http:// http://assets.vice.com/content-images/contentimage/no-slug/005f07f87eecd25266f1a07d60e39ff0.jpg)

[](http:// http://assets.vice.com/content-images/contentimage/no-slug/005f07f87eecd25266f1a07d60e39ff0.jpg)

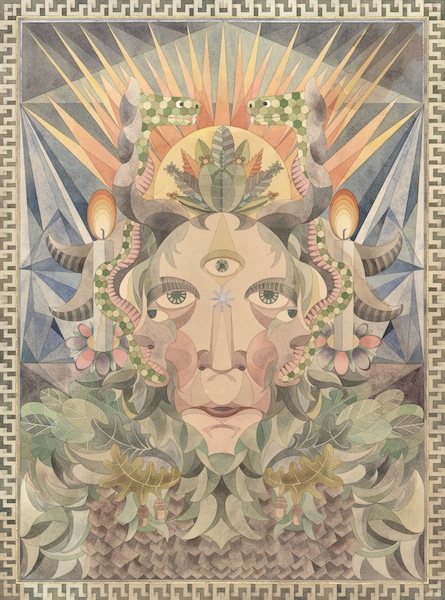

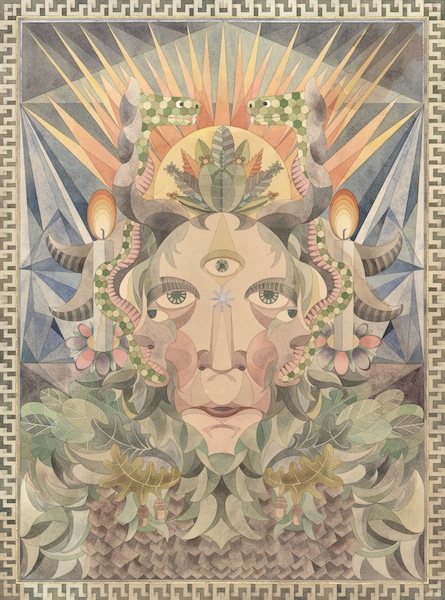

Fredrik Söderberg, Pan II, 2012. Watercolor, palladium, and gold leaf on paper, 74 x 54 cm. Photo by Daniel Andersson. Courtesy Galleri Riis__The New York Times Book Review once said that Barry Gifford has been “chronicling the decline of Western civilization”; another way to look at it is that Barry has been one of the few figures preventing Western civilization from going completely to shit. He’s written more than 40 books, including novels and collections of poetry and essays, and VICE has had the pleasure of publishing a few of his short stories over the past few years.So when he sent us his previously unpublished “Alligator Story,” we of course jumped at the chance to share it with the world. We’ve paired Barry’s text with new works by Swedish artist Fredrik Söderberg, whose occult-inspired imagery gives us the same sorts of chills that Gifford’s stories do. A kid wearing a Tampa Tarpons t-shirt came running up the street shouting, “Some cracker just shot a gator!”Roy and his uncle Buck were in the driveway of the house on Oakview Terrace, rinsing down the boat. They had just come in from fishing out of Oldsmar and had been gone since five o’clock that morning; it was now 6:30 in the evening. They hadn’t had much luck, having boated several kingfish and a few mackerel, but they’d run on sharks everywhere and had to cut lines to get rid of them. The weather had been spotty, the water in the Gulf was cloudy and there were periodic brief showers. It was just the two of them, so they’d had a lot of time to talk. Roy was 12 and a half years old and he loved to listen to Buck, who was 45. Buck was full of information on almost any subject. He was well-traveled and well-read and today he had been teaching Roy about navigation, explaining a rhumb line, which is a course that makes the same angle with each meridian which it crosses; it is constant in direction throughout and always appears as a straight line on charts.“But the curve of shortest distance between any two points on the earth is always an arc of a great circle,” Roy’s uncle told him, “the sort of circle which would be marked out if we were to slice the earth into two halves, passing the cut through the ends of the course and the center of the earth. The shortest path will always be a great-circle course.”Buck had been a lieutenant commander in the navy during the war, and he was a civil and mechanical engineer; sometimes his explanations were too esoteric or complicated for Roy to absorb, but his uncle was always careful to show Roy what he was talking about.“It’s the wind you have to pay the closest attention to,” said Uncle Buck. “The winds will control the course more than mathematical considerations.”As the kid in the Tarpons t-shirt ran by, Buck asked him, “Where’s he got it?”“On the little pier at the end of Palmetto,” the kid shouted.Buck cut off the hose and went into the utility shed and came back out with a sheathed knife and a hatchet. He handed the hatchet to Roy and said, “Come on, nephew, let’s go down there.”Roy and his uncle walked along River Grove under massive hanging moss and cut across the narrow skiff launch to Palmetto Street, which they followed down to the little pier. When they got there they saw a skinny man about 40 years old wearing only a pair of gray trousers with the butt of a pistol sticking out of the waistband and a dark brown Remington Ammo cap slicing up the belly side of a six-and-a-half-foot-long alligator. The man’s pants, chest, and arms were spattered with blood.Buck and Roy watched him work for a minute, then Buck said, “What are you going to do with the hide?”The man was working fast and he did not look up.“Throw it away. There’s a $500 fine you get caught with it. All I need’s the meat.”Roy and his uncle and two boys who were about eight or nine years old and had been swimming in the Hillsborough River watched the man hack and tear feverishly at the carcass. It was still very hot although the sun had begun to go down. Roy knew that it was against the law to shoot a gator without a permit; he guessed that the man didn’t have permission to kill alligators, so he wanted to take what was edible and get going.When the man had finished carving up the belly, he crammed the meat into a canvas sack, stood up, wiped his knife on his right trouser leg, and said to Buck, “I’ll leave the rest to you, then.”The man walked off with the sack over his left shoulder. Roy noticed that he was barefoot and his right leg was considerably shorter than his left. The bag full of gator meat seemed to help keep him balanced as he made his way up the pebbly incline from the dock and disappeared behind the hanging moss.Buck unsheathed his knife, flipped what remained of the alligator onto its stomach and told Roy to chop off the head.Roy hesitated and his uncle said, “Come on, nephew, we don’t want Fish and Game to find us. Run your fingers along the top of the spine and find the soft spot.”

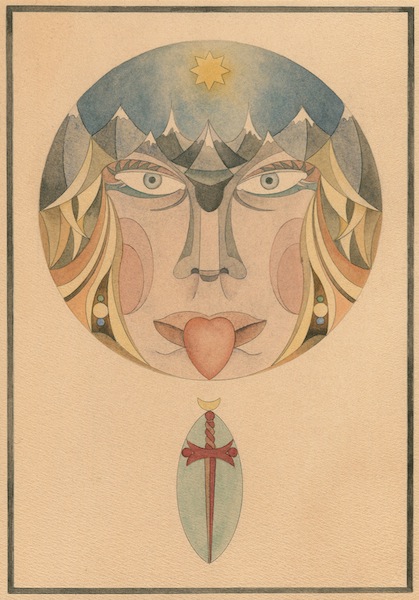

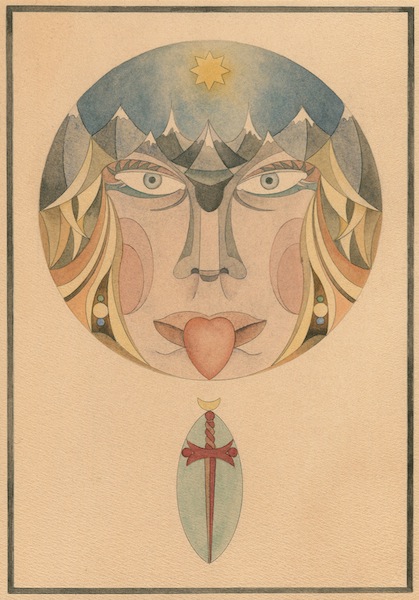

Fredrik Söderberg,_ Yet Time to Turn_, 2011. Watercolor and gold leaf on paper, 29 x 22 cm. Photo by Daniel Andersson. Courtesy Galleri RiisThe ridges along the gator’s back were hard as stones and sharp-edged but not abrasive like a shark’s skin. Roy’s fingers found what felt like a seam two inches behind the head and with both hands wrapped tightly around the handle of the hatchet raised it just above his right shoulder and brought it down into where he judged the seam to be. The blade cut a half-inch into the hide before meeting resistance from muscle and tendon. Roy dropped down from his squatting position and straddled the snout with a knee on either side of the gator’s head resting on the planks. The two boys watched intently as Roy hacked away until the head began to separate from the rest of the body. It took about 15 or 20 minutes to sever the head entirely. When Roy stood up his legs and arms were trembling and his hands hurt.“Pull the head away,” said his uncle, “and stand back.”Buck knelt on the gator’s back from the opposite end and began cutting at the hide. Roy stood with the two boys and observed as Buck swiftly but carefully skinned the ancient-looking reptile. Sweat streamed down Roy’s uncle’s face as he worked, cutting evenly as he progressed from neck to tail, taking particular care not to mutilate the feet. The sun had been down for three hours before Buck completed the job. Roy and the two boys, who were cousins named Rupe and Rhett, were seated cross-legged on the pier.“That was tough, huh?” Rupe said.“Alligators have survived for tens of thousands of years,” said Buck. “They don’t live in houses, like people do, so they have to be protected from the elements.”“God made ’em tough,” said Rhett.“What you gonna do with the head?” asked Rupe.“You can take it, if you like,” Buck said.Rupe and Rhett stood up and together they lifted the head.“Whoa, it’s heavy,” said Rupe, and they dropped it. “We can’t carry it all the way to my house.”“Your mama wouldn’t let you keep it anyhow,” said Rhett.“Shove it into the river,” said Buck.The cousins slid the head to the end of the pier and pushed it over. There was a small splash when the head hit the water. It floated on the surface for a few seconds, then tilted backward so that the mouth half opened and grinned at them before the head sank out of sight.“Them were some terrible lookin’ teeth,” said Rhett.Buck kicked what was left of the gator’s guts, bones, and intestines into the river, then lifted the hide under the front legs.“Grab the tail with two hands,” he told Roy. “Put your arms underneath. So long, boys.”Rupe and Rhett watched Roy and his uncle carry off the hide.Back at the house, Buck brought out from the garage a board about six feet long and three feet wide. He and Roy centered the hide on top of it, then Buck tacked it down so that it was stable. He went into the house and came back out with a box of salt and sprinkled the salt liberally all over the hide.“Pick up the other end,” Buck said, and he and Roy carried the board with the gator skin tacked to it around to the backyard and set it down on the ground. Buck took two cinder blocks and placed them down five and a half feet apart, then he and Roy picked up the board and set it down end to end on the blocks.“It’ll be all right here for now,” said Buck. “The sun will hit it first thing in the morning, then we’ll hoist it up onto the garage roof in the afternoon to dry out.”Buck looped his right arm around Roy’s shoulders.“You did a great job, nephew. I know that head didn’t come off easily.”“You did the real work, Unk. You skinned the gator like a Seminole would.”Both Roy and his uncle were covered with blood and gristle.“How is it you were able to keep your concentration the way you did while you were skinning him?” asked Roy. “I mean, you hardly said a word for two hours.”Buck pulled his blood-stained shirt off over his head and threw it down.“I started thinking about your grandmother’s second husband, the one who raised your mother. He hated me and I hated him, and so I imagined that I was skinning him instead of the alligator.”“Why did he hate you?”“For no good reason, really. I’m almost 14 years older than your mother. He disliked the fact that my mother had been married before, so he resented my existence. Some men are like that; some women, too.”“Did he hate my mother?”“No, she was a young girl, and he sent her away to school when she was old enough. I was almost a man, it was easier for him to hate me.”“My mother never talks about him; all I know is that he died.”“He had a heart attack after he and your grandmother were married for ten years; then she remarried my father.”“You must have really hated the guy to imagine that you were skinning him.”“I pretended that he was still alive but barely conscious and that he knew what I was doing but was too weak to do anything about it. I imagined that he didn’t die until after I skinned him entirely.”“Did he do anything terrible to you?”“He banished me from his house, even though my mother and sister lived there. To see me, your grandmother had to meet me somewhere else, in a park or at a restaurant. Whenever she gave me money she made me promise that he would never know that she had.”“That’s crazy, Unk. How could she allow that to happen?”“I don’t know, Roy. People do all sorts of crazy things.”Buck unfastened his belt and let his pants drop to the ground. His skinning knife was in its sheath, which was still strung on the belt.“I’m glad I never had to meet him,” said Roy.“He wouldn’t have hated you, nephew. What’s terrible is that I still harbor such awful feelings for a man who’s been dead for 25 years. It’s no good to keep that kind of poison in you because after a while the poison starts to work on you. I hope you never have to hate anyone like that.”“I hope I won’t, either.”“All right, let’s wash up and get some dinner.”“Why didn’t we save the head?”“The only way to preserve it would be to soak it in formaldehyde. Too much trouble. The catfish are feasting on it.”“I bet those cousins are telling their folks about the alligator now.”“Come on, Roy, get your clothes off.”The head was scary, Roy thought, but it was beautiful, too. It was too bad that Rupe or Rhett hadn’t kept it.

Fredrik Söderberg, Pan II, 2012. Watercolor, palladium, and gold leaf on paper, 74 x 54 cm. Photo by Daniel Andersson. Courtesy Galleri Riis__The New York Times Book Review once said that Barry Gifford has been “chronicling the decline of Western civilization”; another way to look at it is that Barry has been one of the few figures preventing Western civilization from going completely to shit. He’s written more than 40 books, including novels and collections of poetry and essays, and VICE has had the pleasure of publishing a few of his short stories over the past few years.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

Fredrik Söderberg,_ Yet Time to Turn_, 2011. Watercolor and gold leaf on paper, 29 x 22 cm. Photo by Daniel Andersson. Courtesy Galleri RiisThe ridges along the gator’s back were hard as stones and sharp-edged but not abrasive like a shark’s skin. Roy’s fingers found what felt like a seam two inches behind the head and with both hands wrapped tightly around the handle of the hatchet raised it just above his right shoulder and brought it down into where he judged the seam to be. The blade cut a half-inch into the hide before meeting resistance from muscle and tendon. Roy dropped down from his squatting position and straddled the snout with a knee on either side of the gator’s head resting on the planks. The two boys watched intently as Roy hacked away until the head began to separate from the rest of the body. It took about 15 or 20 minutes to sever the head entirely. When Roy stood up his legs and arms were trembling and his hands hurt.

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ

ΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΗ