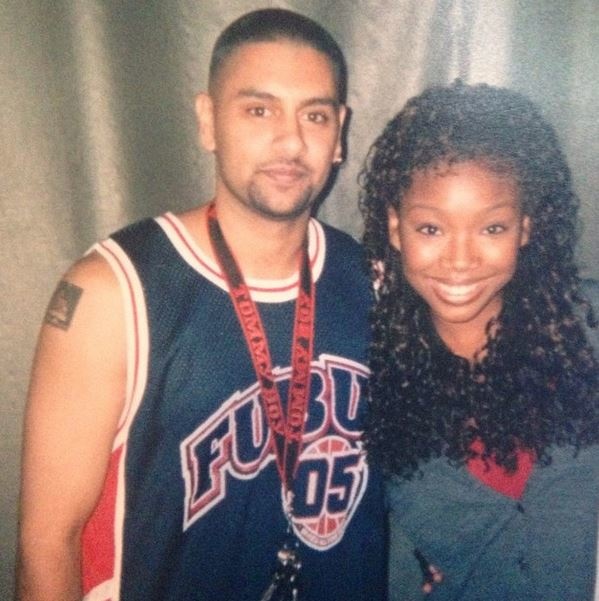

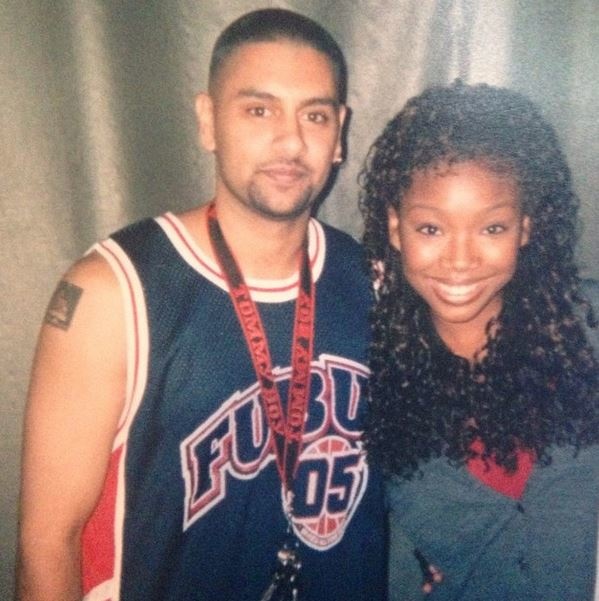

If you’ve heard hip-hop music on Toronto radio in the last 18 years then you know Paul Parhar’s voice as Mastermind. Currently residing on Flow 93.5, Parhar has watched as hip-hop has transformed Toronto’s culture from “T-dot” to “the 6ix.” He’s had a front row seat for each transition, and at times has even acted as a guide from behind the curtain. “I was sitting in Calgary in 2006 and I got a phone call,” recounts Parhar. “They say ‘we got somebody who wants to come have a meeting with you, take you out to dinner, and pick your brain about the industry. They’re just starting their rap career, and they want to research and get as much great advice as they can. You’re in radio, you’ve done hip-hop, you know artists.’ I was like ‘Okay, who is it?’ And they go ‘Well, he’s a kid. He’s an actor on Degrassi, but he’s starting his rap career.’”Paul Parhar was born in Toronto’s Mount Sinai hospital in 1972, the son of Indian immigrants who Parhar himself describes as “the hardest fucking workers.” He lived in Scarborough for the first 8 years of his life before his parents moved to a slightly more central North York neighbourhood, northeast of Toronto’s downtown core. During one of his routine trips into the city, Parhar came face to face with his first taste of hip-hop. “We came outside at the Yonge Street side at Eaton Center, and there was this big crowd of people in a circle watching someone breakdance. I was fucking enamored with it. I remember climbing on top of this electric box just so I could see better. It blew my mind.” Parhar wandered around his neighbourhood of Leslie and Finch, trying to find others who shared his passion. “I was in my school park and a guy had his cardboard and his ghetto blaster and he was playing, like Art of Noise. That’s what people were break dancing to: Kraftwerk and Art of Noise. I wasn’t really hearing ‘hip-hop,’ this was around ’83 or ’82.” Mastermind with BrandyBut if Parhar wanted to listen to the music coming from those boomboxes on his own time and not just at outdoor dance battles, his options were limited as Canadian radio stations hadn’t yet shifted towards playing “funky” music. “There was an AM station that did some stuff late night. I would hear the odd funky thing on the weekend, whether it was Deadly Hedley [Jones] or Chris Sheppard.” Even then, the music that those DJs would play would very rarely be blended or mixed. “Then all of a sudden, Beat Street came out and things started getting a little more commercialized. I remember compilation companies were putting out these breakdance albums and they would come with a poster on how to breakdance.”Amongst the commotion of his newly discovered subculture becoming part of the mainstream, Parhar went looking for music beyond the compilation tapes he convinced his parents to buy him. Through his breakdancing friends he found out about 88.1 CKLN, a radio station that would play hip-hop on Saturday as part of DJ Ron Nelson’s three hour radio show, Fantastic Voyage. “I had to sit on my parents deck in the backyard, I had a coat hanger on the antenna because they only had like 50 watts, and it was still so staticy, but I was like ‘nobody talk to me on Saturday from 1 to 4 PM, because this is all I’m doing.’ I would buy tapes and I would just flip the tape and record three hours straight, because that’s the only hip-hop I could get.” From that point on, Ron Nelson became Paul Parhar’s biggest inspiration.

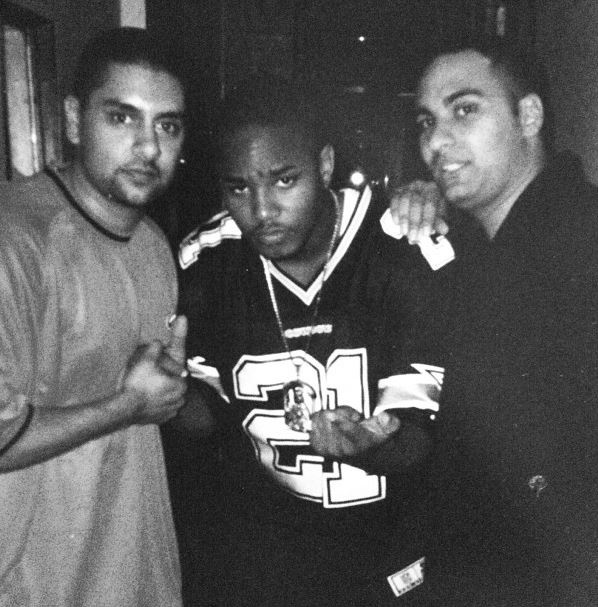

Mastermind with BrandyBut if Parhar wanted to listen to the music coming from those boomboxes on his own time and not just at outdoor dance battles, his options were limited as Canadian radio stations hadn’t yet shifted towards playing “funky” music. “There was an AM station that did some stuff late night. I would hear the odd funky thing on the weekend, whether it was Deadly Hedley [Jones] or Chris Sheppard.” Even then, the music that those DJs would play would very rarely be blended or mixed. “Then all of a sudden, Beat Street came out and things started getting a little more commercialized. I remember compilation companies were putting out these breakdance albums and they would come with a poster on how to breakdance.”Amongst the commotion of his newly discovered subculture becoming part of the mainstream, Parhar went looking for music beyond the compilation tapes he convinced his parents to buy him. Through his breakdancing friends he found out about 88.1 CKLN, a radio station that would play hip-hop on Saturday as part of DJ Ron Nelson’s three hour radio show, Fantastic Voyage. “I had to sit on my parents deck in the backyard, I had a coat hanger on the antenna because they only had like 50 watts, and it was still so staticy, but I was like ‘nobody talk to me on Saturday from 1 to 4 PM, because this is all I’m doing.’ I would buy tapes and I would just flip the tape and record three hours straight, because that’s the only hip-hop I could get.” From that point on, Ron Nelson became Paul Parhar’s biggest inspiration. Mastermind, Cam'ron, and Russell PetersRon Nelson hosted his rap show on college radio for free, so he’d throw all-age parties at Toronto’s Masonic Temple to supplement his income—parties that the teenage Parhar would attend almost religiously. “They would stack the sound systems, the memories I have of that time are so fucking amazing. I remember seeing Public Enemy there. I won tickets to an LL Cool J show through Ron’s show too, that was my first concert.” It wasn’t long until Parhar’s obsession with the music became an obsession with the medium. ”I’m listening to Ron on Saturday, I’m taping it, I’m learning. All of a sudden I fell in love with radio.” Soon Parhar gathered enough courage to venture into the Ryerson University basement where Nelson recorded to ask his idol for an autograph. Nelson saw something in the young fan with his bag full of vinyls, and decided to recruit Parhar onto his street team to promote his events. Parhar gleefully accepted the role, and during the long car rides spent putting up posters, Nelson would quiz his team about the credits for the rap songs that came on the radio, with Parhar always answering all of the questions rapidly.Parhar’s interest in Fantastic Voyage became fanatical, with him dialing into the station every time the show was on. Ron Nelson decided to have some fun with Parhar, and extended the game they would play in the car onto the radio waves, quizzing Parhar whenever he’d call in. “It was either name that tune, where he would play a piece of the record and I would say what the record was, or he would give me a line from the record and I would name it.” It wasn’t long until Parhar earned himself a nickname from his idol, “I got all these questions right live on the air, and he said ‘you’re Mastermind.’”

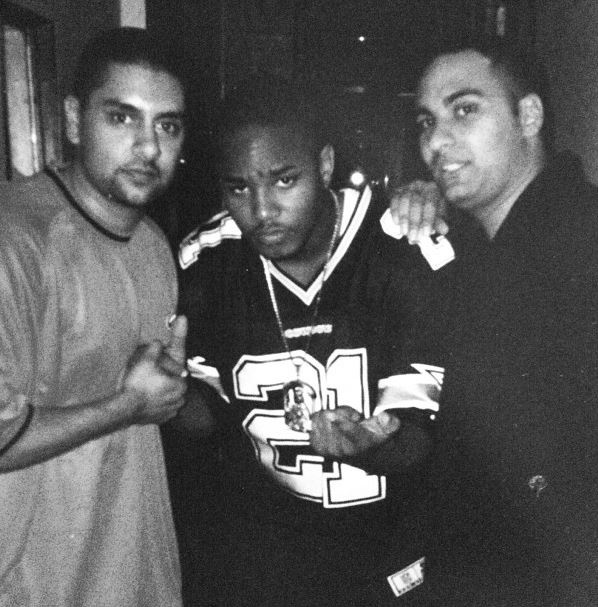

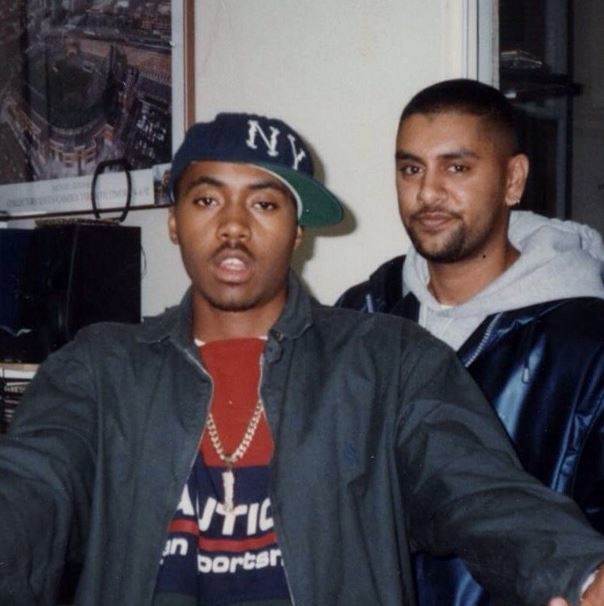

Mastermind, Cam'ron, and Russell PetersRon Nelson hosted his rap show on college radio for free, so he’d throw all-age parties at Toronto’s Masonic Temple to supplement his income—parties that the teenage Parhar would attend almost religiously. “They would stack the sound systems, the memories I have of that time are so fucking amazing. I remember seeing Public Enemy there. I won tickets to an LL Cool J show through Ron’s show too, that was my first concert.” It wasn’t long until Parhar’s obsession with the music became an obsession with the medium. ”I’m listening to Ron on Saturday, I’m taping it, I’m learning. All of a sudden I fell in love with radio.” Soon Parhar gathered enough courage to venture into the Ryerson University basement where Nelson recorded to ask his idol for an autograph. Nelson saw something in the young fan with his bag full of vinyls, and decided to recruit Parhar onto his street team to promote his events. Parhar gleefully accepted the role, and during the long car rides spent putting up posters, Nelson would quiz his team about the credits for the rap songs that came on the radio, with Parhar always answering all of the questions rapidly.Parhar’s interest in Fantastic Voyage became fanatical, with him dialing into the station every time the show was on. Ron Nelson decided to have some fun with Parhar, and extended the game they would play in the car onto the radio waves, quizzing Parhar whenever he’d call in. “It was either name that tune, where he would play a piece of the record and I would say what the record was, or he would give me a line from the record and I would name it.” It wasn’t long until Parhar earned himself a nickname from his idol, “I got all these questions right live on the air, and he said ‘you’re Mastermind.’” Mastermind with NasAlthough Nelson was well respected by Parhar, the general public didn’t look favourably on him. “People used to shit on Ron. The public would say ‘oh he talks too much,’ and I don’t know if it was just trendy or what, but people would just hate him,” remembers Parhar. Jokingly, Parhar recorded a pause tape that looped the phrase “fuck, Ron” and sent it to Nelson, who played it on the radio as a way of addressing his detractors. This would be the first time Mastermind’s mix was played on the air, and his reputation rapidly grew in the local scene. “So now there was this hype about a 13-year-old kid who was answering all these hip-hop questions, so the next week Ron wanted me to come to the station. I went to the station and all these people came to meet me, all these local DJs.”By the time he hit puberty, Mastermind’s profile had grown in the tight-knit community to a level he couldn’t expect. “I was 14, and I had an older friend who I’d play sports with who was in York University. They had a campus radio station in CHRY, and they didn’t have their FM license yet, but they were getting it and my friend told me about it. So one day we took the bus up to the university, I went in, he introduced me to the program director and told him I was interested in doing a hip-hop show. The program director goes ‘yeah, yeah, yeah that’s great, but do you know Mastermind?’ I went ‘that’s me!’ And he goes “We’ve been looking for you! I heard you when you were on the radio two weeks ago. Dude, you’re amazing!” Parhar walked away from that meeting with his own radio show on Wednesday nights from 6 to 9 PM.

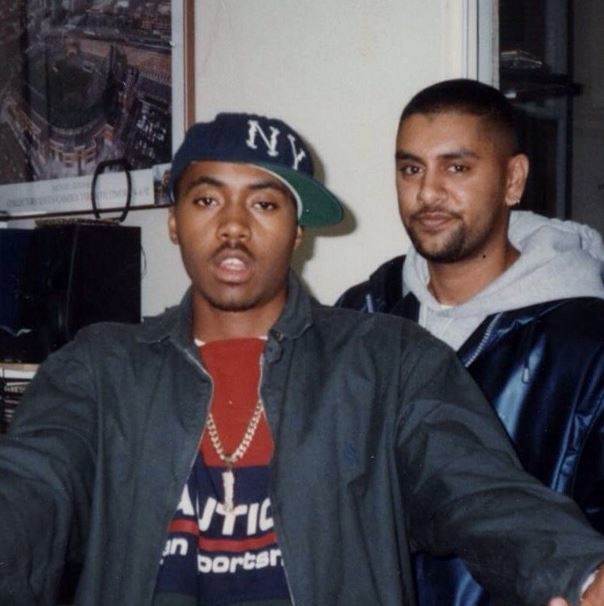

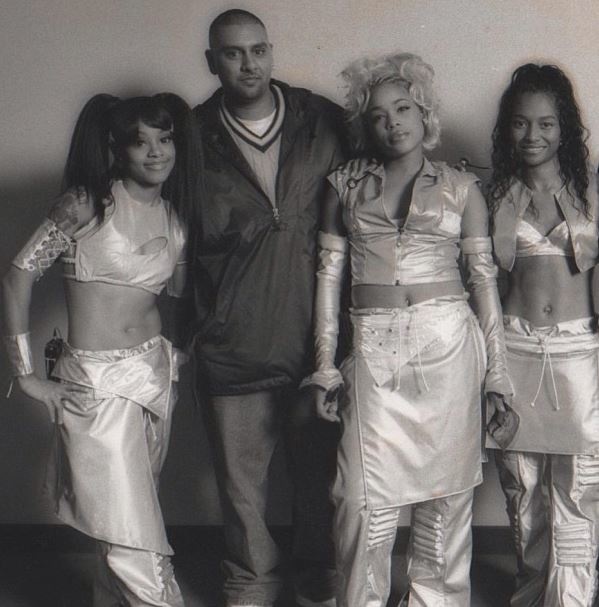

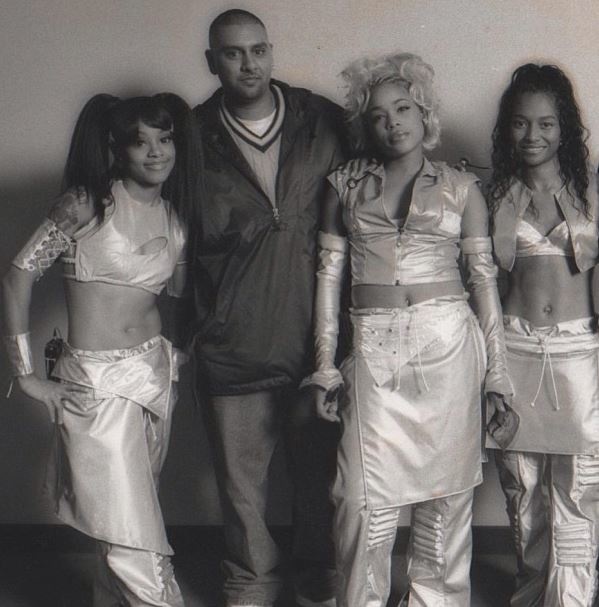

Mastermind with NasAlthough Nelson was well respected by Parhar, the general public didn’t look favourably on him. “People used to shit on Ron. The public would say ‘oh he talks too much,’ and I don’t know if it was just trendy or what, but people would just hate him,” remembers Parhar. Jokingly, Parhar recorded a pause tape that looped the phrase “fuck, Ron” and sent it to Nelson, who played it on the radio as a way of addressing his detractors. This would be the first time Mastermind’s mix was played on the air, and his reputation rapidly grew in the local scene. “So now there was this hype about a 13-year-old kid who was answering all these hip-hop questions, so the next week Ron wanted me to come to the station. I went to the station and all these people came to meet me, all these local DJs.”By the time he hit puberty, Mastermind’s profile had grown in the tight-knit community to a level he couldn’t expect. “I was 14, and I had an older friend who I’d play sports with who was in York University. They had a campus radio station in CHRY, and they didn’t have their FM license yet, but they were getting it and my friend told me about it. So one day we took the bus up to the university, I went in, he introduced me to the program director and told him I was interested in doing a hip-hop show. The program director goes ‘yeah, yeah, yeah that’s great, but do you know Mastermind?’ I went ‘that’s me!’ And he goes “We’ve been looking for you! I heard you when you were on the radio two weeks ago. Dude, you’re amazing!” Parhar walked away from that meeting with his own radio show on Wednesday nights from 6 to 9 PM. Mastermind with TLCMastermind learned from his mentor and began his own side-hustle of selling mixtapes featuring the music he was playing on the radio. He’d sell it to his extensive fan base, managing to pocket some spending money in the process. Mastermind released mixtapes regularly for the better part of a decade, until some friendly competition from Baby Blue Soundcrew resulted in the Canadian Recording Industry Association becoming aware of the illegal compilations. “What they did that I didn’t do is that they started making CDs. They didn’t do anything wrong other than bringing more attention to what we were doing as DJs. So prior to making CDs, it was a small thing. No one really gave a fuck. It was on a cassette and record labels knew that cassettes deteriorate and no one is going platinum on a cassette. But what happened was since Baby Blue Soundcrew were making CDs, what they were doing is basically compilation of the biggest songs that were out. They got super popular, and then because it was a CD and they made it look like it was real, people would go into HMV and other records store and ask for this Baby Blue Soundcrew album.”It didn’t take long for the authorities to crack down after it became clear to companies that there was money being lost. “In 1999 the CRIA basically raided all the mom-and-pop stores. They even raided the plant in Scarborough that was doing all the duplicating for pretty much all the DJs. They raided that place and confiscated equipment, tapes, money, and they ticketed people. That fucking ended mixtapes and CDs for quite awhile,” explains Parhar, while adding a silver lining. “But that also led to both myself and Baby Blue Soundcrew getting our respective record deals.” These deals were supposed to capitalize off the built-in fanbase the DJs had by legally licensing the music, but due to turmoil between Virgin and Universal, Mastermind was only able to record a limited amount of his last official mixtape. He recorded 50 tapes in total featuring artists like The Rascalz, Kardinal Offishall, Choclair, and Saukrates alongside American rappers. “I made 48 tapes, then tape 49 was The Setup, which was all Canadian artists freestyling over already established records. Basically that was the promo tool that we used to help promote Volume 50, which was my actual album.”

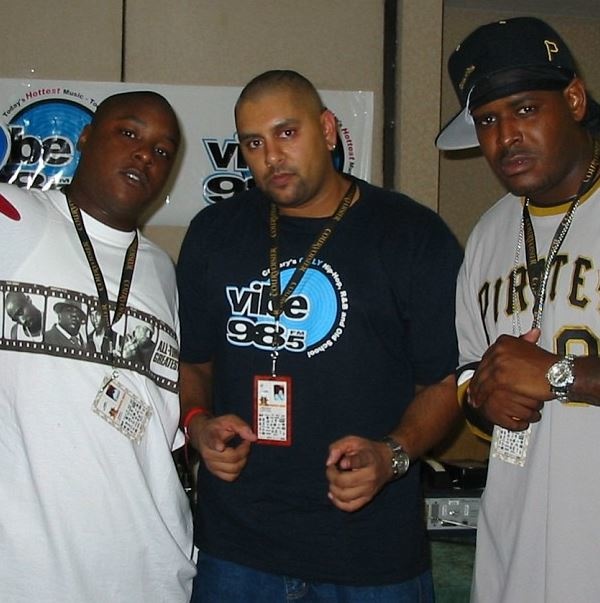

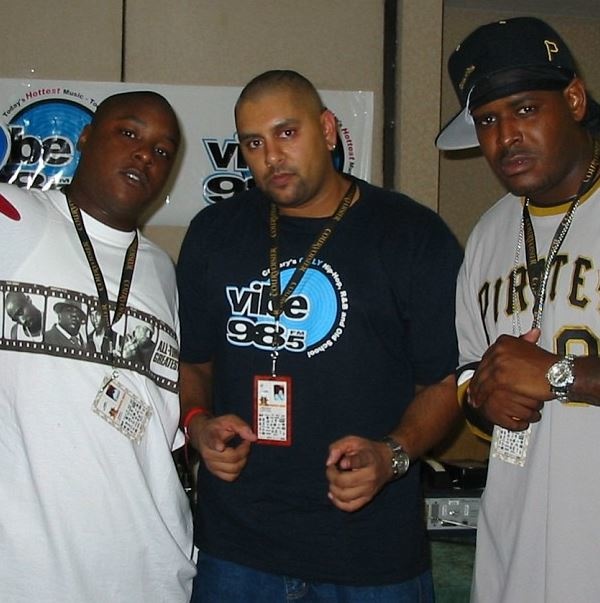

Mastermind with TLCMastermind learned from his mentor and began his own side-hustle of selling mixtapes featuring the music he was playing on the radio. He’d sell it to his extensive fan base, managing to pocket some spending money in the process. Mastermind released mixtapes regularly for the better part of a decade, until some friendly competition from Baby Blue Soundcrew resulted in the Canadian Recording Industry Association becoming aware of the illegal compilations. “What they did that I didn’t do is that they started making CDs. They didn’t do anything wrong other than bringing more attention to what we were doing as DJs. So prior to making CDs, it was a small thing. No one really gave a fuck. It was on a cassette and record labels knew that cassettes deteriorate and no one is going platinum on a cassette. But what happened was since Baby Blue Soundcrew were making CDs, what they were doing is basically compilation of the biggest songs that were out. They got super popular, and then because it was a CD and they made it look like it was real, people would go into HMV and other records store and ask for this Baby Blue Soundcrew album.”It didn’t take long for the authorities to crack down after it became clear to companies that there was money being lost. “In 1999 the CRIA basically raided all the mom-and-pop stores. They even raided the plant in Scarborough that was doing all the duplicating for pretty much all the DJs. They raided that place and confiscated equipment, tapes, money, and they ticketed people. That fucking ended mixtapes and CDs for quite awhile,” explains Parhar, while adding a silver lining. “But that also led to both myself and Baby Blue Soundcrew getting our respective record deals.” These deals were supposed to capitalize off the built-in fanbase the DJs had by legally licensing the music, but due to turmoil between Virgin and Universal, Mastermind was only able to record a limited amount of his last official mixtape. He recorded 50 tapes in total featuring artists like The Rascalz, Kardinal Offishall, Choclair, and Saukrates alongside American rappers. “I made 48 tapes, then tape 49 was The Setup, which was all Canadian artists freestyling over already established records. Basically that was the promo tool that we used to help promote Volume 50, which was my actual album.” Mastermind with Sheek Louch & JadakissEventually, with the added pressure of taking care of a growing family, Mastermind took a job across Canada as the music director of Calgary’s Vibe 98.5 in 2001. “I didn’t want to move to Calgary,” confesses Parhar. “You don’t leave Toronto to go to a smaller marker. It’s ego, it’s work, but eventually it’s like, I need to make some moves. Plus I was going to launch a huge hip-hop station, which was pretty exciting.”As for the dinner with Drake, Mastermind doesn’t remember the specific details of the evening, but he knows that he would give the same advice to any other aspiring artist who sought it from him: “I didn’t sugarcoat anything about the Canadian industry and how hard it is. I’ve always given advice to anybody who’s asked. I tell them, don’t worry about Canada. Go out and conquer the States and the rest of the world, because then Canada will definitely follow suit. But if you try to be a Canadian artist here, you’re only gonna have a certain level of success, and that’s just the bare bones truth about it.

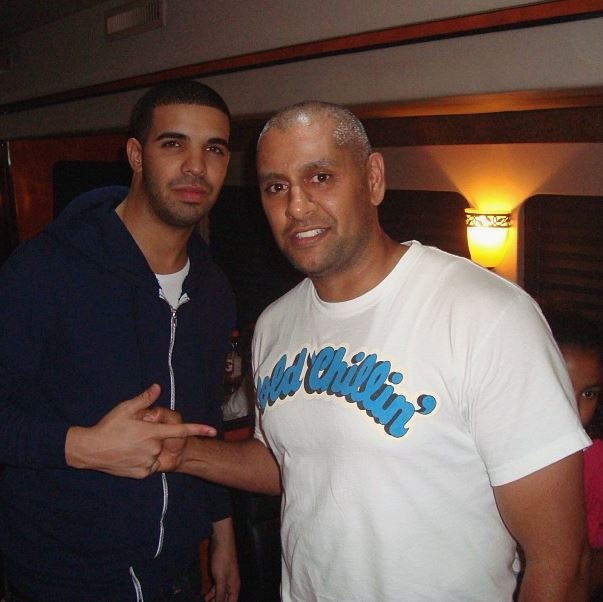

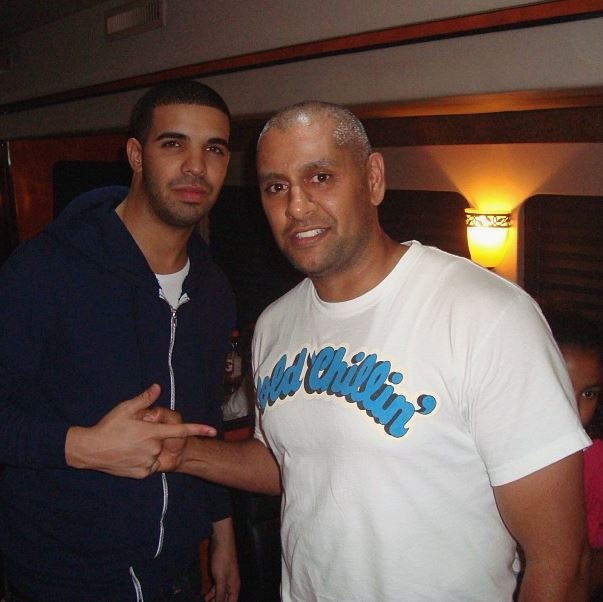

Mastermind with Sheek Louch & JadakissEventually, with the added pressure of taking care of a growing family, Mastermind took a job across Canada as the music director of Calgary’s Vibe 98.5 in 2001. “I didn’t want to move to Calgary,” confesses Parhar. “You don’t leave Toronto to go to a smaller marker. It’s ego, it’s work, but eventually it’s like, I need to make some moves. Plus I was going to launch a huge hip-hop station, which was pretty exciting.”As for the dinner with Drake, Mastermind doesn’t remember the specific details of the evening, but he knows that he would give the same advice to any other aspiring artist who sought it from him: “I didn’t sugarcoat anything about the Canadian industry and how hard it is. I’ve always given advice to anybody who’s asked. I tell them, don’t worry about Canada. Go out and conquer the States and the rest of the world, because then Canada will definitely follow suit. But if you try to be a Canadian artist here, you’re only gonna have a certain level of success, and that’s just the bare bones truth about it. Mastermind & DrakeHaving since returned to his hometown of Toronto, Mastermind is arguably one of the most knowledgeable sources on hip-hop in the city. When asked if he can see any common thread connecting the rap music that’s ever come out out Toronto, he pauses for a beat. “For the most part what I’ve loved about Toronto rappers is the pride that we take in lyricism. People can knock Drake all they want, but dude can actually fucking rhyme. Like he can spit some bars when he wants to, and he’s got a great witty way of putting his words together. I actually think that’s a long standing thing about Toronto, when you think back to Maestro before he even became Maestro and he was Ebony MC and fucking battling dudes. It was all about his lyrics. Same with Michie, it was all about lyrics, and any other rapper that came up after them, it was about really spitting lyrics.”Slava Pastuk is the editor of Noisey Canada - @SlavaPAll photos courtesy of Mastermind's archives

Mastermind & DrakeHaving since returned to his hometown of Toronto, Mastermind is arguably one of the most knowledgeable sources on hip-hop in the city. When asked if he can see any common thread connecting the rap music that’s ever come out out Toronto, he pauses for a beat. “For the most part what I’ve loved about Toronto rappers is the pride that we take in lyricism. People can knock Drake all they want, but dude can actually fucking rhyme. Like he can spit some bars when he wants to, and he’s got a great witty way of putting his words together. I actually think that’s a long standing thing about Toronto, when you think back to Maestro before he even became Maestro and he was Ebony MC and fucking battling dudes. It was all about his lyrics. Same with Michie, it was all about lyrics, and any other rapper that came up after them, it was about really spitting lyrics.”Slava Pastuk is the editor of Noisey Canada - @SlavaPAll photos courtesy of Mastermind's archives

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement