A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Let it be said that we must live in particularly interesting times when John McAfee, one of the most controversial people the world of technology has ever produced, can get arrested in a foreign country for tax evasion … and people barely even notice.

Videos by VICE

But that’s what happened earlier this month—and as a result, McAfee is sitting in a Spanish jail, waiting to be extradited.

A lot has been written about him over the years, but I’d like to focus on one part of his life that has perhaps been overshadowed by his unusual existence over the past decade: The fact that, in the late 1990s, he was a social media innovator.

That innovation? A chat app called PowWow that, despite a certain McAfee imprint, was well ahead of its time. Here’s why you probably don’t remember it.

1994

The year John McAfee resigned from McAfee Associates, the company he founded in the 1980s that became a major distributor of antivirus software. The company, a multibillion-dollar giant today, nearly sold to Symantec years before it hit its later peaks, but McAfee was talked out of selling his namesake firm by a low-level analyst at a venture capital firm that realized the fundamentals of the company were quite good. While he later left, he did so with a lot more money than he would have had previously.

How John McAfee turned a Winnebago sabbatical into his second startup

Everyone has likely heard the story of how Jeff Bezos quit his job in the financial industry and came up with the business plan for Amazon while on a cross-country trip to what would become his new home in Seattle. (Bezos, of course, didn’t drive as he hashed out this plan; his then-wife, MacKenzie, was behind the wheel.)

Less heralded, but perhaps more interesting, is the trip that John McAfee took throughout the Western U.S. after he quit his leadership role with his namesake antivirus company.

Like Bezos, McAfee’s excursion led to the launch of a new company. Unlike Bezos, this was McAfee’s second round in the Winnebago, which is where the antiviral legend got his start when he was first trying to pinpoint computer viruses sometime in the late 1980s.

As recounted in a 1997 article in the legendary tech business magazine Red Herring, McAfee’s second encounter with a Winnebago came after he had a minor heart attack, which led him to sell his company and go on an extended trip to the Rockies, where he encountered various Native American tribes. Those tribes directly inspired his follow-up company—and its inevitable location in the relatively tiny Woodland Park, Colorado, near Pikes Peak.

When McAfee gave away his antivirus software in the 1980s, he did so because of a New Age philosophical approach that suggested that software shouldn’t be sold. Likewise, he found inspiration in the Native American tribes he visited during this mid-’90s journey. Per Red Herring:

There’s an entrepreneur living in the shadow of Pikes Peak, Colorado, who thinks software is a living tree and can’t be sold. So in his last venture he gave it away. He sees the Internet as the physical manifestation of what Indian shamans call “the golden thread,” and his latest project, Tribal Voice, is an attempt to capitalize on this mystical vision.

And where did that mystical vision lead him? It led him to multimedia chat software that was years ahead of the instant messaging trend that would eventually take hold thanks to AOL, ICQ, and later Skype.

The software Tribal Voice created, PowWow, may have been one of the first social networks, thanks to its focus on “tribes” as an organizational strategy. It was a great spot to converse—if you could look past the website.

“PowWow lacks the robust business-oriented features of packages such as WebPhone, but if you’re looking to specialize in a chat-room atmosphere and don’t mind enduring the ham-radio quality of the conversations, PowWow might be just the ticket.”

— A passage from a 1996 review of PowWow in PC Magazine, which noted that the application’s big strength was the size and reach of its community. Not so hot? The voice chat, which didn’t work so well on the modems of the era, at least at the time of testing.

Tribal Voice’s initial marketing strategy appropriated Native culture—with a huge side of cringe

The software was good, but Tribal Voice had branding that very much reflected its unusual founder. It had a website (at tribal.com, of course), that was in many ways pure cringe … that seemed to almost make a mockery of the Native American culture that inspired the company.

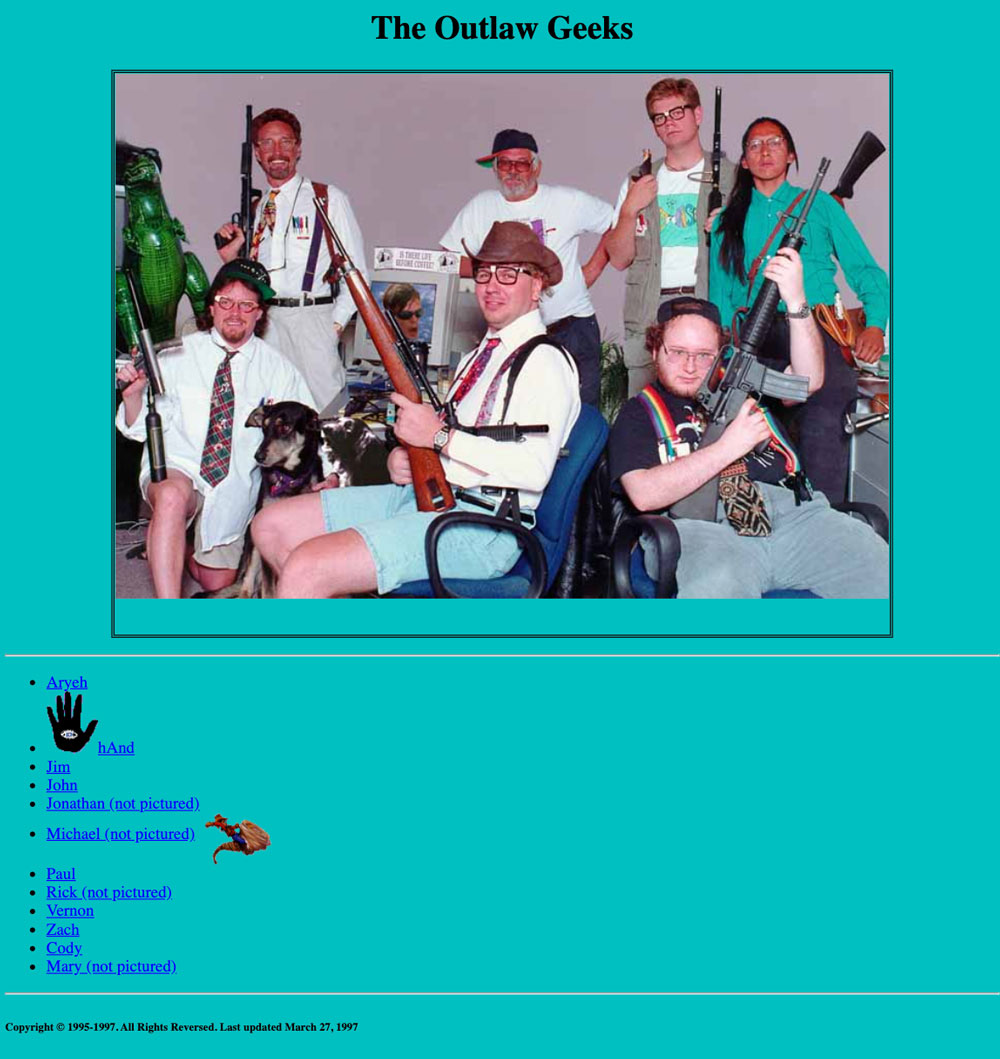

On one early version of the Tribal Voice site, the about page included a photo of McAfee and company, under the banner “The Outlaw Geeks,” brandishing various types of guns. (Given what we know about McAfee now, it checks out.) And another page featured a “Tribal Voice Yuppie Catalog” which makes one wonder what exactly McAfee learned from his time visiting Native tribes.

The company’s active borrowing of Native American imagery and wording drew the ire of an early online Native American activist, Paula Giese, who called the material on the site “sacreligious.”

“Our Sacred Pipe, sweat lodge, cedar, tobacco, all of our most important symbols, ceremonies, objects, places are not just exploited but desecrated, trashed, by this Tribal Voice corporation, which spent hundreds of thousands of dollars preparing its commercial site, but has advertised itself all over the web as ‘Native Culture,’” Giese wrote.

Giese, who died in 1997, had a notably tense online interaction with McAfee, which is saved on the Internet Archive for all to see. (McAfee’s defense? “This is probably not an appropriate site for teenagers. We are focused on adult issues,” he wrote.)

It also did no favors from a PR standpoint. Gary Flood, a reporter for Computer Business Review who was doing a profile on McAfee, recalled being weirded out by the site’s many inside jokes and garish color scheme. His thoughts:

Initial impressions: geek city, lots and lots of feathers and cosmic colors, man, a major section of the site being devoted to the self-admittedly crazy ramblings of an escapee from the Pikes Peak Mental Facility who is obviously some loon one of the programmers thinks is cool, and what seems way too much stuff about ‘adult’ web sites and marijuana.

Nonetheless, despite the somewhat disturbing web branding scheme (which Flood had been told was likely going away at the time of his early 1998 interview), the software’s community-building mentality, something of a combination of IRC and Skype, found a lot of early success. Despite the cringey way the site showed its inspiration, the tribes concept did lead McAfee and company in the direction of social media years before most people cared.

An early Tribal.com page dating to 1997 pinpoints more than 700,000 separate users on its “white pages,” which were pages that people could sign up for to find people to chat with. (Unlike, say, Twitter, you actually had to look people up as if you were using a phone book.) PowWow, says McAfee, attracted numerous walks of life.

“We let people set up whatever tribe they want. We have, for example, a gay Hispanic tribe,” McAfee told Red Herring. “Our biggest tribe, believe it or not, is an Icelandic tribe. We also have an enthusiastic user community in Rio de Janeiro.”

Forgotten today, PowWow was a nice little success at the time—especially after it ditched the weird website. On the way to making things more professional, they even brought in a new CEO, Joseph Esposito (who, true story, once pushed back on a story of ours that discussed his prior employer, Encyclopaedia Britannica). And McAfee, still just a few years off from leaving a hugely successful company that he created, had no trouble attracting investors, unusual site or not.

But the PowWow software attracted a major enemy that would eventually land a body blow: AOL.

$10M

The amount McAfee made from selling half of Tribal Voice in 1997. McAfee would later cash out entirely, selling the company to a dot-com incubator, CMGI, in 1999, for $17 million. (Not a bad payday.) In a 2010 piece on McAfee in Fast Company, Tribal Voice employee Jim Zoromski implied that McAfee was actually scared off by the company’s success—just as he was with McAfee Associates years earlier. “When John was at Tribal Voice, the growth rate was incredible,” Zoromski said. “But when it got to be too popular, it started to feel too much like work, and John wasn’t interested.”

How AOL took a bite out of Tribal Voice

With Tribal Voice, John McAfee and his rag-tag crew of programmers in small-town Colorado were early to one of the most important early trends in technology during that period—instant messaging.

But the fact that PowWow is basically forgotten while its most high-profile competitor, AOL Instant Messenger, is fondly remembered today, may not exactly be an accident.

By 1998 or so, McAfee’s follow-up company was seeing real success in one of the hottest areas of the early internet—in part because McAfee knew a lot about both building communities and selling technology to the public.

(McAfee, infamously, helped to hype up the craze around the Michelangelo virus in 1992 … which helped to boost the profile of his antivirus app.)

He could also sell technology to companies: Shockingly, given the photo I just shared with you above, Tribal Voice scored a partnership with friggin’ AT&T, with PowWow helping to power the instant messaging capabilities of the telecom giant’s WorldNet service.

Part of what attracted WorldNet to PowWow comes down to its ability to work on multiple networks, including AOL and MSN Messenger. This gave PowWow—and AT&T—a competitive advantage, as it could work across networks with ease.

This wasn’t something, however, that AOL liked. In fact, AOL didn’t like anyone encroaching on its instant-messaging turf and took steps to protect it at all costs: It outright purchased ICQ, attempted to block competitors from using similar terminology to AOL Instant Messenger (a fight it fortunately failed at), and took steps to block Microsoft’s MSN Messenger from its users.

Smaller IM services during the period were trying to make a case for interoperability, so that users of one network could reach friends on any of them. For a time, AOL offered guides that described how this was done to allow for the development of Unix-based clients for AIM. The problem was that its competitors read those posts as well, and PowWow found itself pulled into a messy battle as it attempted to raise up its own application by adding AIM support, and admitting it was doing so without any approval from AOL.

Tribal Voice created a mortal enemy with this move, and it likely hastened the demise of the PowWow tool, which found itself at the center of a high-profile battle with AOL that worked to make the case for interoperability between instant messaging clients. It was a game of chicken for a while; PowWow would add functionality to enable AIM support, AOL would shut it down.

At one point—which should be noted, came after McAfee had left the company—Tribal Voice and other clients found itself making this case in front of the FCC.

According to a New York Times article from the era, new CEO Ross Bagully evoked Ronald Reagan: “Mr. Case, on behalf of the IM industry and users everywhere, tear down this wall!”

But ultimately, the cause of encouraging open IM support came at the cost of the original weird Native American-inspired thing that McAfee built. The new owner lost interest in PowWow entirely, and shut the app down at the beginning of 2001 … while claiming continued interest in IM technology as a whole.

“After careful review of CMGion’s business objectives and strategic direction by its new management team CMGion feels that the PowWow technology is not an integral part of CMGion’s mission,” an FAQ from the shutdown stated.

One has to wonder, if McAfee stayed with the company he started instead of leaning on the easy payout, where it might have gone. After all, he waited with McAfee Associates … and look where that company is now.

It’s so bizarre to think about this product in retrospect.

PowWow was a genuinely innovative product, one that predicted the success of about half a dozen apps that followed it. But even folks that did use it only have faded memories of it. I’m sure I used this program in 1996, but I completely forgot about its existence until I started writing this and went, “Ohhhhh.”

It might come down to the fact that it was simply too early.

Jason Pontin, then the editor of the MIT Technology Review, argued in 2005 that one of the reasons that PowWow didn’t see the level of success that McAfee’s antivirus suite did, despite also being sold for free, was that the market wasn’t ready for his inventions. He was a first-mover in a second-mover market—something that was not true of his first startup, which innovated most effectively thanks to its business model.

“Tribal Voice was the innovator in two emerging markets, now much in the news, whose dynamics are still only partially known. The first is multiprotocol IM. The second is social networking,” Pontin wrote. “Today, thriving companies like Cerulean Studios and LinkedIn can be found in both markets. But John McAfee was there first, even if he didn’t know how to make money from Tribal Voice.”

Today, McAfee is a colorful figure, one of tech’s most interesting and controversial. But despite his success in antivirus software, there’s a strong case to be made that he also should be celebrated as a social media pioneer.

Well, if you can look past the photo.