A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

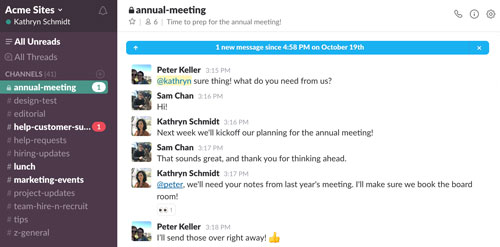

Love it or hate it, the business-focused chat platform Slack clearly has done something right in its four years of existence.

Videos by VICE

(Case in point: It’s worth $5 billion somehow, based on a recent investment by SoftBank.)

It’s particularly strange for many users in the context of what it does.

Breaking down all its integrations and emoji, and it’s basically a smart chat client.

Chat clients, of course, have been around forever—particularly in the form of Internet Relay Chat, or IRC, and while it was pretty successful, it never crossed into pop culture the way Slack has.

Let’s ponder why the walled garden won out over the open protocol.

“IRC started as one summer trainee’s programming exercise. A hack grew into a software development project that hundreds of people participated in and became a worldwide environment where tens of thousands of people now spend time with one another.”

— Jarkko Oikarinen, a Finnish college student and server administrator, discussing how he created IRC in the foreword to a 2004 book. The protocol, created in 1988 after he found himself with extra time one summer—and with the desire to improve an existing protocol, OuluBox. He did a lot more than that, with the protocol quickly spreading globally.

An anecdote of what IRC was like back in 1996, featuring the Butthole Surfers

It’s not often that I have to rely only on my memory to bring to light a piece of internet ephemera, but in this case, I don’t really have any other option. (So if I get some details wrong here, blame the fact that the Internet Archive was just getting off the ground at the time this happened.)

See, back in the mid-90s, online chats with celebrities were all the rage, and MTV made a point of drawing attention to this fact, repeatedly. Heck, it even hosted its own, most assuredly looping in random stars to hang out at its offices in NYC.

One day, MTV hosted an online chat featuring the Butthole Surfers, then riding high on the success of their one mainstream hit, “Pepper.” This was a weird time in American history, when a band named Butthole Surfers could find itself featured in your local newspaper, and the band could feature Erik Estrada in its music videos.

Anyway, the chat was supposed to be on AOL, but this was roughly around the point when AOL was peaking, either just before or just after it had introduced its unlimited pricing tier, so it was facing some infrastructure issues, making AOL’s chatroom a no-go that night.

So MTV moved the chat with the Butthole Surfers to IRC at the last minute, meaning that if you were in the mood to talk to Gibby Haynes, Paul Leary, and King Coffey about their hit major-label album that featured a graphic drawing of a pencil stabbing someone’s ear, you were hopping into the open internet to converse.

(My memory of the chat, which, again, I have no record of: I asked them what their next video would look like, and they told me “a long, warm tunnel.” There was no next video for that album.)

This is basically the only memory I have of IRC being mainstream in any way, shape, or form. Generally, my memories of IRC revolved around chatting about emulators and how awesome Quake was. It was, really, the place you went when you were sick of deathmatches.

It was the kind of nerdy endeavor that predated ICQ, that predated AOL Instant Messenger, and that reflected the wild, somewhat unhinged nature of the internet in the same unvarnished way as Usenet.

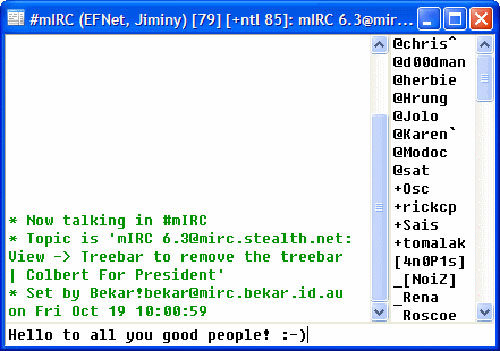

It had its own lingo. That lingo could be seen in the big networks of the era, such as EFnet, which is literally named in reference to a disagreement that happened more than a quarter-century ago, and Undernet, which formed partly in response to the rise of “netsplits,” or the separation of a node from a broader network.

One of the most memorable things about IRC, besides the conversations, were the power dynamics—for example, the ease at which you could get banned from a channel, or a server. Look at a mod the wrong way? Kicked out, or even banned from the channel. Accidentally log into the server too many times in a couple of minutes? Banned from the server.

In many ways, IRC’s dynamics have been discarded with for most online interactions. The control of a certain chat room or server was much more obvious way back when. Now, that control is very much still there, but put into the hands of, say, Facebook, rather than a bunch of annoying moderators.

The most popular IRC client, mIRC, reflects a different era of software development

If you break things down, the reasons Khaled Mardam-Bey developed his popular Windows client mIRC aren’t all that dissimilar to the reasons Stewart Butterfield and company built Slack. But the results, in some ways, couldn’t be more different.

While a student in London, Mardam-Bey saw a lot of potential for a chat client, but the options out there at the time he started developing were mostly text-based and weren’t very easy to use. So in 1994, he started developing what became mIRC, a client that eventually became hugely popular around the world after its early 1995 release. At its peak, it had been downloaded hundreds of millions of times.

The client, which was so extensible that it included its own scripting language, was definitely one for power users, though in an FAQ, Mardam-Bey says that he’s been picky about what he actually adds.

The things he did add, however, even reshaped the way that IRC in general works. For example, one of the best-known IRC gimmicks, the “trout slap,” which was introduced to mIRC in 1995, was directly inspired by a Monty Python sketch. It was not uncommon to see “[Name] slaps [Other name] around a bit with a large trout” back in the day.

“Most of the features in mIRC were requested by users. Developing software is a fine balancing act: you want to be attentive and receptive to user requests but at the same time you want to avoid software bloat,” he writes. “Of the many feature requests I have received over the years, only a handful have actually made it into mIRC.”

The client reflects an era when many of our most popular applications came from individuals, not conglomerates—a side effect of the then-popular shareware model, of course.

It was one of a variety of apps of this nature, some of which became unlikely household names in the process. But unlike the developers of Winamp, Eudora, or Paint Shop Pro, Mardam-Bey never sold his stake in mIRC to a larger firm—and he still updates it to this day, as a full-time job with some volunteer help.

The result is that the client reflects something of an old-school experience. If you were to download mIRC for the first time now, with no knowledge of what it’s like, you’d find an experience quite similar to what it was in 1997. Which is surprising, because nearly every part of our computing experience has changed since.

In the best way possible, it’s like downloading a time capsule.

“I know a bot / She’s called Anna. She’s called Anna, / and she can ban, ban you so hard / She rears her head in our channel / I want to tell you I know a bot”

— A sample of an English translation of the Basshunter song “Boten Anna”, a 2006 EDM hit in Europe, sung in Swedish, about (I kid you not) an apparent IRC bot that turns out to be a real person. The music video for the song prominently features mIRC along with an IRC-based plotline.

How the differences between IRC and Slack highlight a larger philosophical debate

For the past few years, a bit of a debate has been brewing in the open-source space about Slack—particularly how it differs from IRC in general.

Programmer Drew DeVault perhaps highlighted the issues that come with Slack for open source projects, including the fact that Slack’s memory footprint is sizable, and the fact that programmer channels aren’t the desired use case for the platform.

But the biggest is perhaps ideological—it’s a proprietary platform being used for free and open-source software, when IRC, which is an open protocol, is already free:

In short, I’d really appreciate it if we all quit using Slack like this. It’s not appropriate for FOSS projects. I would much rather join your channel with the client I already have running. That way, I’m more likely to stick around after I get help with whatever issue I came to you for, and contribute back by helping others as I idle in your channel until the end of time. On Slack, I leave as soon as I’m done getting help because tabs in my browser are precious real estate.

Others are less critical of the program’s open-source status, but instead see the issue as one where a business clearly improved upon an existing idea by simply removing or polishing years of cruft.

If you’re a regular Slack user with some familiarity with IRC, usually mIRC, you might immediately reflect on how similar the platform is to the chat protocol of yore. But when you break it down and closely analyze the two applications, the differences become more clear.

For one thing, you don’t have to connect to a server at all when using Slack, which adds some of the natural complication to the process; for another, some of the dynamics of using IRC are much more apparent. In some ways, the process of joining networks and channels feels closer in dynamic to setting up your email client—it’s complicated, and kind of a lot of work. We expect a lot more hand-holding these days.

In a piece for DZone, writer Rodrigo Kyle Mehren points out that Slack, while a robust interface, has managed to repackage the same basic ideas as mIRC without veering off to the side.

“Those icons—I have no idea what they mean. The burden of caring enough to find out scares me,” he writes of mIRC’s interface. “It’s overkill. Every feature and function can be controlled at a very granular level. You can even write your own bots for it, to carry out routine administrative tasks or play Uno. Wait, what?”

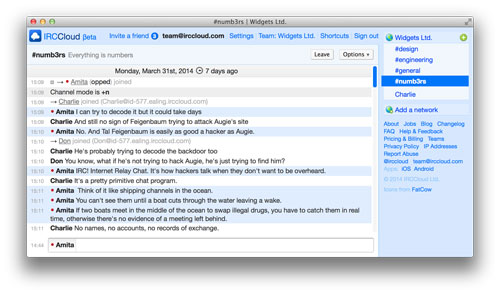

And certainly, attempts have been made to fix both Slack’s issues and to reframe open-source conventions around Slack—for example, Gitter is a clear attempt to build a version of Slack for developers, and MatterMost and Rocket.chat have emerged to reconsider some of the ideological issues.

Heck, there are even tools like The Lounge and IRCCloud, IRC clients designed to work kinda like Slack.

If Slack makes IRC better, then maybe it was all worth it.

The nice thing about IRC compared to some other vintage internet protocols is that it never really died, nor did it lose its place in the conversation, like Gopher unfortunately did. Programmers are still all over IRC, even if it never gained unicorn scale like Slack has.

The networks that defined IRC back in the day, mainly EFnet and Undernet, are still online, even if they’ve perhaps kept at it thanks to their old-school charm. Freenode, meanwhile, has helped to keep online communities around open-source programming active and productive for more than two decades.

But IRC has never reached the broad scale of many of the open-source projects hosted on Freenode. Is it because of problems with the platform, or was it better marketing?

Or to broaden the question some: Why is it, out of all the prominent internet protocols in use during the early ’90s, only two of them—email and the World Wide Web—have managed to hold on in a way where most people use them on a regular basis, especially since the existing tools were often replaced by walled-garden equivalents like Facebook, Twitter, and Slack?

Perhaps it’s because they were the ones that were the easiest to explain. IRC is great—it was even the subject of a hit EDM song!—but it definitely has never been polished.

It’s the kind of place that slaps you around a bit with a large trout.