This story contains graphic descriptions of violence.The far-right, while it never left, is back in a big way.It’s more vocal, in your face, and prominent than it has been in years. Across the world we’re seeing rallies where chants echo with “blood and soil” and Nazis are emboldened enough to publicly show their faces. These aren’t benign forces at work, they claim lives. Atomwaffen, a neo-Nazi terror cell, was connected to five deaths last year, and an anti-racist protester was run down and killed at a Charlottesville rally last summer.

Advertisement

There are myriad reasons for the far-right’s sudden growth: the proliferation of the internet allows for neo-Nazi spaces like Storm Front and the Daily Stormer to flourish and actively recruit; the announcement that in a few decades whites will no longer be the majority in Western countries has stoked hate; and even some high-level politicians have hinted sympathy with their movement. There is no doubt it’s here and it doesn’t seem to be going away and we need to acknowledge that.For a long time, the majority of research and deradicalization efforts surrounding extremism were hyper-focused on the threat of Islamic terrorism. Ignoring this other homegrown threat was a costly mistake. As Heidi Beirich, director of SPLC’s Intelligence Project, puts it “there isn't too much known about deradicalization of this type.” In the last year we’ve seen some efforts spring up that work to remove people from this movement—Life After Hate (which had its funding pulled by the Trump administration) and the Exit programs in Sweden and Germany—but they are still woefully underfunded. To put it bluntly, we’re playing catch up. "It's like we've forgotten we have another homegrown terror threat that's pretty serious here as well. Nothing has been done about it,” Beirich told VICE.

One of the ways to learn about this subject by is speaking to people who, in the past, harboured despicable views. "I think it's really important to know how people get into these movements. What are the social, familial dynamics that lead to someone becoming radicalized,” said Beirich. “We can't prevent it if we don't know how that happens and formers are a very good source of information on those processes. Formers are the one who can give us an understanding of a successful path out."

Advertisement

As Beirich explains, knowledge is power when it comes to ideological movements like this, and by knowing how some of these "formers" left, we can use that to fight the growing ideological war on our own soil. Often it's family or other close relationships that encourage an exit. Here are four of those stories:

Tony McAleer

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Tony McAleer was one of Canada’s most influential neo-Nazis—being heavily involved in the White Aryan Resistance. McAleer told VICE that he had a relatively normal childhood but when things started going wrong for him at home and at school he was sent to a British boarding school. In England, McAleer was exposed to the punk scene, and through that the skinhead scene.His entry into the movement culminated after his return to Canada when, at a Black Flag show, he was approached by two skinheads and joined their ranks. McAleer told VICE that “In order for me to have their protection, I had to have their respect, and in order to get their respect I had to engage in the same violence that they did.” That was Tony’s introduction into the violent world.Over his time in the movement, McAleer was a key figure in growing the white power agenda in Canada. He started a white power phone service and one of the first white power websites. “I had seen what the internet was and it very quickly became obvious to me that this was the place to be and this is where we should be going,” he said. He linked his group with other white supremacists, pulled stunts that gained media attention and turned Vancouver into a hotspot for the ideology. “For a while, we were the only skinheads in Vancouver but it started to grow in the mid-80s. National socialism felt like it was the ultimate rebellion.”

Advertisement

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

By the late 90s, he started to question everything and planning his exit. “A big thing was the birth of my daughter and my son—but it was a process, not a moment. I became a single father when they were about four and six and that was the final catalyst. At this time my mom had to take them to preschool because if they knew who their father was, the kids wouldn’t play with them. I was so high profile it was affecting their quality of life, so I left,” he said.McAleer called his exit strategy "fading to black". "I didn’t say ‘fuck you, I’m out’ I just became less and less available. People seemed OK with that because I had done so much, I wasn’t expected to do any more," he said. "Around ‘98 or ‘99 I met this girl online, she was East Indian and we hooked up. I knew as we were doing that I was deprogramming myself, I was consciously aware of that. I knew if I did this I could never go back to the movement because I’m a race traitor, right? So I did things that would prevent me from being able to go back as a way of consciously deprogramming myself.”

Frank Meeink

Frank Meeink is one of America’s most notorious former neo-Nazis—his story was the basis for the film American History X. Growing up in Southern Philadelphia, Meeink was raised in a tough neighbourhood by a single mother. When he was young his mother married a man Meeink told VICE was “very abusive, a drunk and a drug addict” who would dole out “crazy punishments.” After he was kicked out of his house at 13 he moved with his dad in east Philly where he started going to a predominately black school. At this school, according to Meeink, there were “a lot of jumpings, a lot of fighting—it was just a crazy school to go to.”

Advertisement

For Meeink, his journey into hatred started with a trip to see his cousin he looked up to in northern Pennsylvania. “My cousin had gone from being a punk to being a neo-Nazi. All these skinheads would come over and they would drink beer and they seemed cool—they had cars, and beer, and girls,” he said. “I liked hanging out with those guys. These guys would like to hear my story about Philly, so these guys would love to talk to me—they never really talked to someone who saw black people every day. My parents weren’t asking me what my day was like, they weren’t asking me why I ran home from school, they didn’t give a shit about me. When these guys started asking me about this stuff, I liked the attention—I was 14.”

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

As Meeink puts it, “it went absolutely crazy from there.” He quickly became a leader in his local movement and was extremely good at recruiting new members. “Racism is the greatest bait-and-switch ever pulled,” he told VICE. “We would just bait people into being racist by saying ‘you want to be proud of your heritage?’ Even the alt-right, which is a neo-Nazi pig with lipstick on it, start with that line of thought. I would say, ‘come to my group, I’ll let you be proud of your heritage.’ But when they would come we wouldn’t even talk about our heritage we would talk about the others and hate them."Meeink was eventually arrested and imprisoned for kidnapping and brutally torturing a rival skinhead gang member. His transition out of the movement came with that prison sentence.

Advertisement

“My change came with just human beings being human beings to me when I needed it the most—they didn’t even realize it. There were black guys that I would play ball and cards within the prison. Life was just different there. There were a couple black kids that were kinda down motherfuckers. Real fucking cool and we’re 17 in this grown-up prison like John Wayne Gacy was there and shit. We would play ball and talk about prison life and girls. They used to just say nice things to me when the people in my Aryan gang were assholes about everything,” he said.

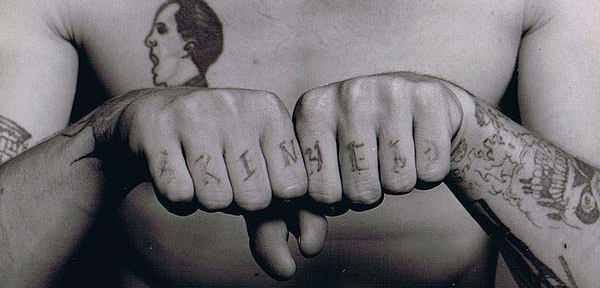

“When I was released, it was confusing. I was still part of the neo-Nazis but I didn’t agree with it. I had a daughter who was a couple months old when I got out of prison and her mother wanted nothing to do with me. I was still a neo-Nazi leader and she didn’t want her around that."With a swastika tattoo on his neck Meeink was having an obviously hard time getting a job but a Jewish man who ran a moving company took a chance with him. Meeink was making $100 a day—life changing money for him at the time—but his hatred for Jews leaked into their interactions. “I just kept thinking in my ignorant anti-Semitic head ‘oh, he’s going to rip me off, he’s a Jew.’ He came over and said ‘I owe you money’ and he gave me $300 and another $100 because I was a good worker.” The man ended up giving Meeink a ride back from Jersey to Philly and they chatted the entire time. “He was being nice to me, he kept telling me to stop calling myself dumb. He was saying stuff that really resonated with me. I had never heard someone say that much good stuff about me. Here I was with a Jewish guy and I have a swastika on my neck, I don’t know what I would do without him. After that day, I took my boots off, I was just done.”

Advertisement

Sign up for the VICE Canada Newsletter to get the best of VICE Canada delivered to your inbox.When an old skinhead friend was killed, Meeink went to the funeral, where all his former friends were done up in full regalia and sieg heiling, much to the embarrassment of the deceased friend's parents. Afterwards, Meeink was invited back to the party. “It was a set-up. There was one guy waiting for me, he sucker punched me and he started screaming out these words to signal the group to start stomping me. Most of my former guys just turned away when I was getting stomped and then they picked me up and threw me down a flight of steps and that was it. It felt at the time, that, you know, I got off easy,” he said.Meeink, alongside McLeer and Angela King (another former neo-Nazi),eventually helped found Life After Hate. He also founded Harmony Through Hockey which uses hockey to help to keep kids from making decisions like he did.

Maxime Fiset

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

For Maxime Fiset, everything started in his late teens. He told VICE that he was bullied a lot in school and that some of those who targeted him were minorities—his dislike for those people grew into racist beliefs. While working as a security guard at a Quebec City Park he met a group of neo-Nazis and “realized I wasn’t alone with my radical, racist ideas.”Fiset founded the Fédération des Québécois de Souche in an effort to link all forms of white nationalists across the province together. “In 2007, I became an organizer in the movement and it lasted until 2012. There was a feeling of belonging that I really craved, I wanted to be a part of something. It was not being part of a crew that made me join in, it was part of being a member of a bigger thing.”

Advertisement

Fiset told VICE that he thought at first he was conflicted with what to do with the movement, but thought “they have this very strong, vital energy that we could use for constructive purposes but all we use it is to get drunk and fight.”

“At my worst point I was a white supremacist, I believed that the white races were superior of course,” he said. “At some point I thought that society was so contaminated with liberalism and Marxism that it kind of had to be reset, there was this thing about killing every non-white that I felt was the logical end to our world-scale project. It’s not something we would have done small scale but we thought, in the end, we would have to cleanse the world. If you read books like Turner Diaries, well, that’s the whole point of the book and that’s horrible.”Things began to change for Fiset when he decided to go back to school, which gave him the space to reconsider some of his viewpoints. “[Around the same time,] I had a daughter and the movement is pretty sexist and racist and these aren’t things I want my daughter to learn. It was clear that from the moment the test was positive she wouldn’t be raised in that, even if I stayed in. I wasn’t hanging out with these guys at that time and it became obvious I had to leave.”“It took me a few years of studying—in around 2015—to realize just how bad my ideas were, why they were so bad and the damage they did. That’s when I came out to some people about my past and that’s when my old friends in the movement started calling me a traitor and it was over them.”

Advertisement

Since leaving the movement, Fiset has become part of the Montreal’s Centre for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence. “The first thing to do if you have a friend undergoing radicalization is not to confront them, because if you go after them hard it hardens their beliefs. In their minds, at the end of the day, you are going to be wrong and they are going to be right. But if you listen to them and ask them questions, open questions, first to understand them better and to instil doubt. Doubt is important because people who are radicalized often don’t doubt their ideas and if you instil doubt you did a good job,” he said.

Christian Picciolini

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

Christian Picciolini was born in Blue Island, Illinois, and by the age of 16 was already a neo-Nazi leader. He founded White American Youth and sang in the band the Final Solution, which was extremely popular in the white supremacy scene and the first American skinhead band to perform in Europe.Picciolini said his family didn't encourage racism, but he felt alienated from being bullied. At a young age he got into white power music and it all began unraveling. “It was this social movement, it was a community, it was a group of friends, a brotherhood, it was all tied through this music which was our propaganda, it was our messaging, it was our education, it was our incitement to violence, it was our gathering and recruitment method. It was very much the core of our propaganda but also the core of our social movement that we were a part of.”

Advertisement

At 14, he first joined a Chicago-based skinhead group when, while smoking a joint in an alley, a man came up and told him that “the Jews and the communist want me to do drugs so I stay docile.” Picciolini told VICE that he was struck by the man's presence and “jumped at the opportunity to be a part of something” and that his attraction to the movement wasn’t “about ideology or dogma, it was about acceptance” and, for a while, he embraced the violence that came with the movement.“There were almost daily street fights, attacks on people by groups of us on random strangers who didn’t deserve it. We found a way to take our own self-hatred and putting it on other people completely absent of the fact that we were angry over things in our lives that we had control over.”

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

At one point in the early 90s, the violence escalated even further. Picciolini and his crew were drunk and went to a McDonalds where they encountered a group of black teenagers. “We were being very belligerent, and started to say it was ‘my McDonalds’ and they had no right to be there." As some teenagers ran out and others appeared to fight back, Picciolini and his crew caught up to one of them and proceeded to beat him “to the point where he was essentially just a heap on the ground and his face was swollen and bloody and he couldn’t move or function," he told VICE. "At one point, and I remember this very, very vividly—it was a turning point in my life—he managed to open his eyes and as I was kicking him his eyes met mine. As I looked into his eyes it was a moment of empathy that this guy could be my brother, someone I care about.”

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

This, Picciolini explains, was the starting point of an exit that would take him years. “I began to really disengage around that time. Lots of things happened around that time, my kids were born, I opened my own business [a white power record store]. I began to meet people at this store, people outside of my social movement—African-American people, Jewish people, gay people. Over a short period of time, I began to see them as human and I started to humanize them and it started to push out and destroy the demonization and hatred I had in my head. This paired with the lasting feeling from the beating Picciolini began to disengage. He was a leader, and suspects he may have had an easier time because he never trained anyone to take over his position. "When I left it imploded, so there was never a major threat to me locally.”Picciolini says fear of starting over stalled him from acting on his doubts. “There was shame, I didn’t know how to make amends, I was trying to outrun it. I didn’t know how to break away. It was the record store where it all started when I recognized that I didn’t want to sell the white power music because I was embarrassed by it. I pulled the music and that was the majority of my revenue so my record store shut down and my wife and child left me because they were not a part of the movement. I almost went from this very visible national figure to nothing and I struggled for years to outrun who I was."

All photos courtesy of interviewees.

He says guilt and shame followed him to this day. "I still feel a lot of shame for that period of my life and how I hurt other people. Not just for the people I considered the enemy but for the innocent young kids I brought into this movement—where doing so drastically changed their trajectories and they may have ended up dead or in prison or with ruined lives.”These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.Follow Mack Lamoureux on Twitter .