MATTE magazine is a photography journal I started in 2010 as a way to shed light on good work by emerging photographers. Each issue features the work of one artist, and I shoot a portrait of him or her for the issue's cover. As photo editor of VICE, I'm excited to share my discoveries with a wider audience.

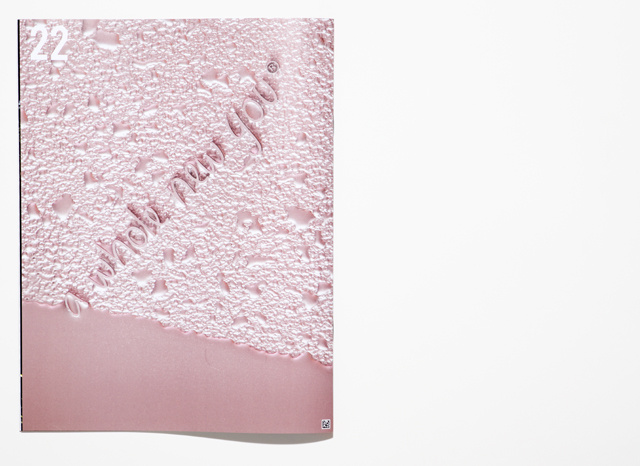

Issue 22 of MATTE features the work of NYC-based photographer Luke Libera Moore. A graduate of Cooper Union, Luke now makes a living on his technical acumen, photographing products and still lifes in a very exacting way for blue-chip clients. His personal work is an outlet for darkly psychological scenes that relate masochicm to fantasy. There is a long tradition of successful commercial photographers doing freaky things after hours, like the violently sexual nudes of Paul Outerbridge Jr. But Luke's work is unmistakably current. Themes of stunted vitality and death pervade the photos, conveyed through athletic and mechanical motifs. A slick gloss lures the viewer in, inviting him to delve infinitely deeper and deeper into these hyperreal images, until his nose hits the glass of the computer screen.

Advertisement

MATTE: There's a high level of gloss with your pictures. What do you do for a living?Luke Libera Moore: I work as a commercial photographer—specifically, cosmetics and fragrances.You photograph perfume bottles.At the moment, yes, and makeup. So I participate in the sleek representational canons of desire on a daily basis.

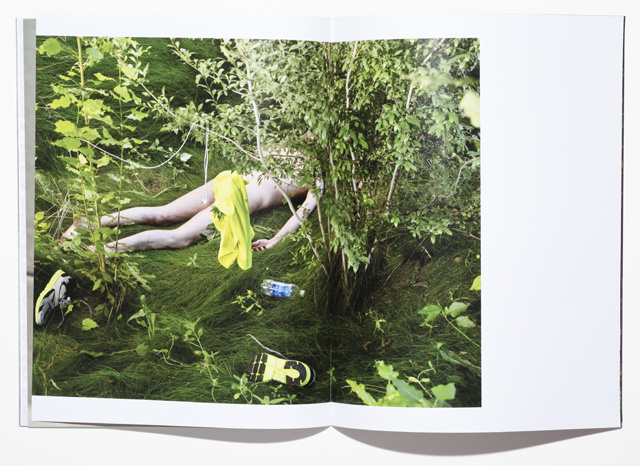

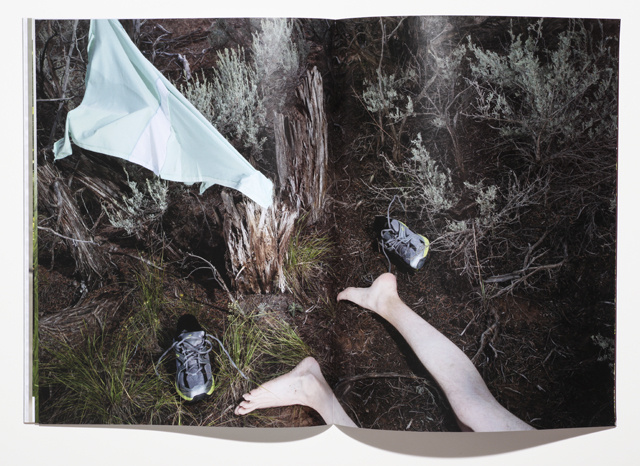

But you get to do darker things with your own work. For example, there is a recurring motif of dead joggers in the magazine. Where did those come from?It was a confluence of quite a few factors. My ideas are tinged with the influence of Romantic-era tableaux painters and photographers—especially the work of Henry Peach Robinson. The original impetus came from visiting my dad in Santa Fe. Last fall, when I was in New Mexico, it had just been raining a lot, which is atypical for the desert, especially during that time of year. His backyard was a ditch that all the rainwater had drained into; it was this incredibly verdant explosion of grasses. Immediately I thought that I wanted my corpse to be found there, lying in the brush.Is that you in the picture?Yes.What is your interest in athleticism?I'm interested in the jogger as a figure of vitality, cut short. But there are other figures I play with—like new home owners and consumers in the current "customization economy," where subjectivity is produced through the consumption and distribution of goods or information.

Advertisement

These are not happy pictures.Yes, but at the same time they are somewhat self-deprecating. There's a sense of humor about them. I think of them as self-conscious melodramas.

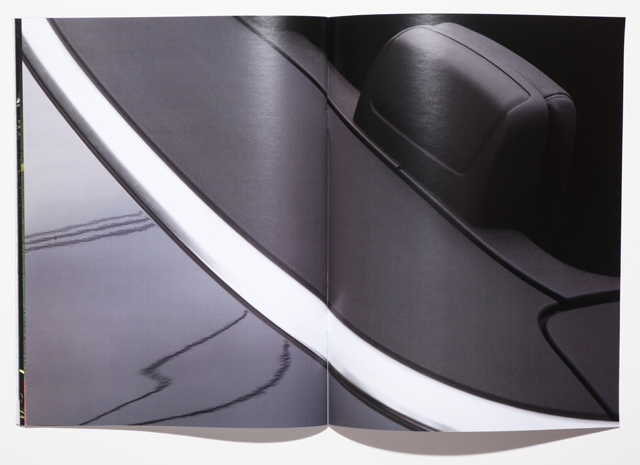

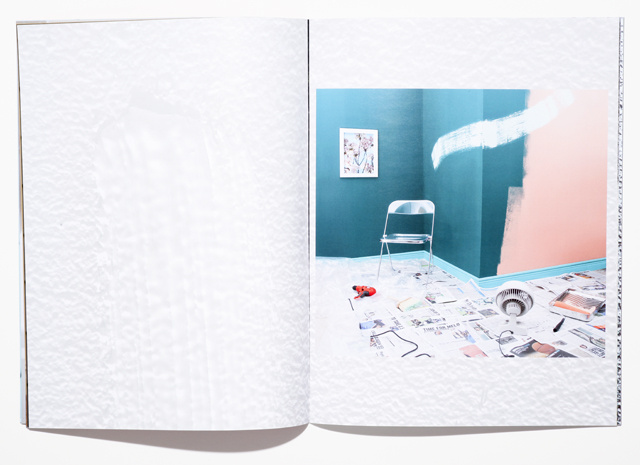

So you lure people in with the polish of these pictures, which after a certain point is kind of grating, and the subject matter is alarming. You're using a lot of camera tricks. You're making it so glossy that the image almost looks computer-rendered. So what's the point of making it in real life?I think that's the point, or, rather, one of the points. This image of a water bottle is not only stack-focused but composited from exposures that combine oppositional lighting techniques, all of which are commonly used in desire-sparking product photography. I'm photographing a lot of vibrant white-plaster casts that I have made for this new body of work called Thing Mapping. When they are lit acutely, they look like computer renderings that haven't had a texture mapped over them yet. But many of them are also evocative of those iconic lunar landscapes from the Apollo 11 mission. I see them as fundamentally alien to what is or has been considered human vision.In this new white work, I'm starting to go full-force into high-res fetishism. I'm thinking of them as residual paraphernalia of a zoom-centric society, living between screens. All I want to do is just zoom into these images until I'm inside of them, swimming. I'm using a medium-format Hasselblad with a digital back (not my own), as well as a specific software, which is the most important thing lending the image its quality. It's a stack-focusing program. I input six to 20 images of the same thing, but I change the focus; the program takes the images apart, pixel by pixel, and renders them into one photo, wholly sharp from front to back. So the depth of field is infinite—again, something completely estranged from the workings of human vision. These banal objects go through a triple removal of sorts. First, they're cast in a solid, homogenous material; then they're transformed into images; then, given more recent photographic technology, their original physicality is left unverifiable. But I'm not interested in eureka moments—moments when someone says, "Oh, I see, it's real." I'm more interested in the uncanny or stupefying confrontation with these mute objects. It's about beholding, not the faculty of understanding.

Advertisement

Where's it all going?My pictures are another space that I'm carrying around with me; there is no end. It's a space I'd like to inhabit, but it also becomes a dark space, because it's necessarily foreign and unattainable. It exists only on the surface of the image. I might not want to hang out there for very long, but I always return. This is another point where my interest in the psychoanalytic conception of the death drive crops up.

Would you say there is an element of eroticism in your pictures?Yes, but specifically a certain masochism. Fantasizing is neccessarily masochistic becase it's eroticizing something that you'll never actually get. Even if the object is attained (which it can't really be, anyway), the fantasy itself as a mental image remains out of reach. It invites pain—a pleasurable pain—and bleeds into some aspects of the sublime.You seem obsessed with control.It's a problem.As a medium, photography allows a lot of control over the viewer. Not as much control as films, though. Do you consider making movies?I made some while I was in school at Cooper Union—they weren't very good. But I would love to be a cinematographer. I would like nothing more. But I would have no idea how to do that because I think I'm terrible at working with other people.That's an advantage of photography. You don't have to.Being alone is the most important thing about my process. Recently, I've been doing a couple things where I needed a model. But there is something about wandering off alone, or being isolated in a dark studio, that is so crucial to me for working. I've always been a solitary and somewhat melancholic kid, and that leads to far-out fantasies.

Advertisement

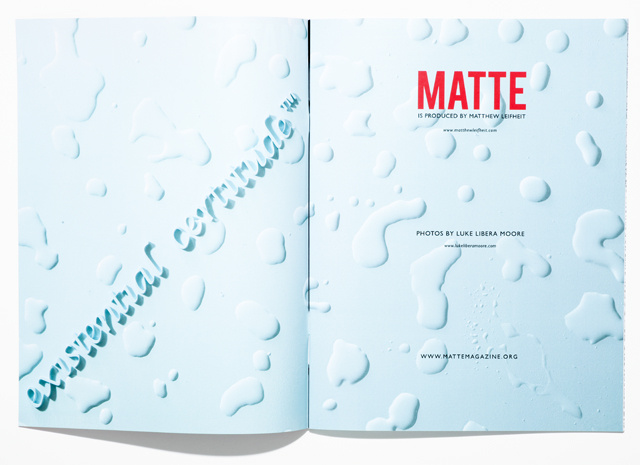

Below are selected spreads from issue 22 of MATTE magazine.

Luke Libera Moore is an artist based in New York. His issue of MATTE can be purchased here.Follow MATTE magazine on Twitter.