PHOTOS COURTESY OF RICHARD NEVILLE

Back in the late 1950s, when Richard Neville finished high school, Australia was in many ways, uh, what’s the word? Oh that’s right…totally fucked. Monarchy-loving Menzies, then in his mid-70s, had been in power since 1949; the White Australia Policy was still officially on the books, Aboriginal people could not vote and ‘integration’ was still seen as a solution. Homosexuality, prostitution and abortion were illegal, carrying sentences that were more a punch in the face than a slap on the wrist and the death penalty was still the ultimate enforceable punishment. Women were not allowed to drink in public bars and all pubs closed at 6PM. Television, barely two years old was beyond dull and other cultural forms and channels of information were either non-existent, heavily censored or banned.

Within this climate in early 1963, small black and white posters appeared around Sydney declaring “Oz Is A New Magazine”. Little notice was taken until April Fools Day when, in the hands of pretty young street-sellers, the first issue of Oz surfaced with the headline of “Abortion”. Six thousand copies sold by lunchtime and a re-print was gleefully ordered by one of Oz’s editors Richard Neville, who called it “the happiest day of his life”. Not long after, Neville and his co-editors Martin Sharp and Richard Walsh, were in court on obscenity charges. For the next three years, Oz continued to be published in Australia and its editors continually appeared in court until they were finally acquitted in 1965 at which point they knew it was time to leave Australia.

Neville and Martin moved to London in 1966 and decided to re-launch Oz. There the magazine, although still humorous, moved in many directions, becoming more and more psychedelic and political. Again they were charged with obscenity and the Oz trials became one of longest and most high profile obscenity cases in history. Both the Australian and London Oz challenged the boundaries of free speech and a film about the London Oz era and the associated trial is set for release soon.

Vice: Where did you grow up?

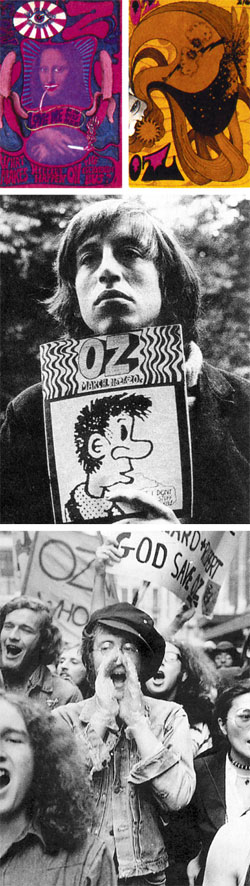

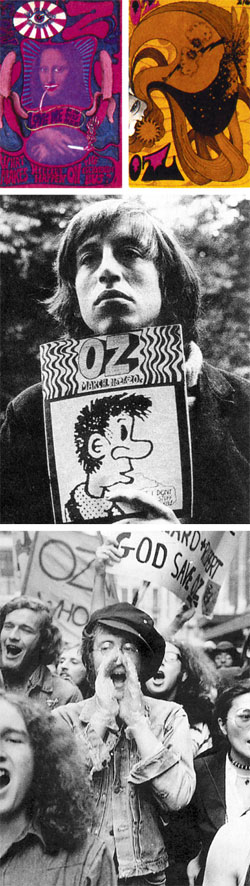

Richard: I grew up in a Sydney suburb of Mossman, which was very dull and unfashionable at that time. A very placid place. There was a lot about the world we didn’t know and would only find out about by accident. Like the revolution in Cuba. When Castro came to power you hardly knew about it: where is Cuba, who is this man? Events that were actually of great significance seemed so far away and so irrelevant. From top: The covers of Oz were always sensational. Richard Neville with a copy of Oz. John Lennon and Yoko Ono join in a pre-trial rally. Over page: Louise Ferrier, Richard’s then girlfriend and Oz cover model.

From top: The covers of Oz were always sensational. Richard Neville with a copy of Oz. John Lennon and Yoko Ono join in a pre-trial rally. Over page: Louise Ferrier, Richard’s then girlfriend and Oz cover model. But then things started to change. People began thirsting for freedoms?

Yes but it happened very slowly. Even then, quite routinely, pop songs that had a sexual reference were banned from the radio.When television came in they started a show, Bandstand, to talk about the ‘new music’: rock n roll. It was actually shot live and hosted by a guy called Brian Henderson, who was well known in Australia at that time and later became the senior newsreader for Channel Nine.

Didn’t you kidnap him from the set?

Ha. Yes, that was pre Oz. God, this is so ancient. It was when I was editing the student paper Tharunka at university. I would have been in my very early 20s. The student council were looking for a stunt to raise money for a charity. I went along with a couple of bulky students and at a signal from me we grabbed Brian, put him in a car and drove him to a place up on the Northern beaches where a lot of other students were waiting and a huge party was going on with lots of booze. He’d never had so much fun in his life. We asked for a ransom and Channel Nine very quickly agreed to pay it. I think it was the happiest day of his life.

That could never happen now.

Probably not. Australian students by about 1961 were beginning to think there was something a bit too placid about Australia, there was injustice going on, there was censorship happening, a war was being fought and no one even had a clue why it was being fought. So they were starting to have a conversation about it.

For me the turning point was when an American comedian, Lenny Bruce, turned up in Australia to do a concert. He gave his first performance in Australia at a pub in Sydney and I couldn’t afford to go but I remember the next morning all the newspapers were headlined ‘Comedian Is Obscene At Performance’. And it was all cause he’d uttered a four-letter word on stage. I thought he was great so I tried to get him a show at the university but at the last minute the Vice-Chancellor intervened and said that Lenny Bruce wasn’t allowed on campus. I thought this is too much; enough is enough. And that was really the germ that led myself, and other less-self-promoting types, to start the magazine Oz.

Did you go to university with the other guys?

Richard Walsh, my co-editor, was one of the editors of Honi Soit, the Sydney University newspaper. Martin Sharp came to see me with a friend called Garry Shead, another painter, who is now incredibly highly priced, and they had just started a newspaper for art students called the Arty Wild Oat. From here, it all just fell into place.

So you launched and ended up in court not long after. What was the charge?

It was on infantile grounds. But now I’m going to have to make a confession, I hardly ever tell this story. But, because the parents and lawyers of some of the other editors were incredibly conservative, we were advised to plead guilty because it was assumed that we would be acquitted with no conviction recorded. And that’s what we did. We felt like it was the French Revolution all over again but when it came to court we were wearing suits and apologising and we got convicted anyway. That taught me a lesson. I’ve never pleaded guilty in my life again and never will.

I imagine the case broke a lot of new ground.

Yeah, and generally the issues of the magazine in question were radical, funny and beautifully illustrated by Martin. A lot of my tutors and professors at university even gave evidence on the grounds that we were in the public interest because the magazine had artistic and literary merit. Unfortunately the magistrate was incredibly biased so the trial ran on for a long time and eventually went all the way to high court. It went on for years but we were still able to publish other issues and Oz became a sort of megaphone of free speech for people in Australia.

What kind of topics did you tend to cover?

A really wide range—anything to do withpopular culture. We had incredible writers like Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer. There was a lot of Australian politics and certainly the war in Vietnam featured. We’d often get our pictures from the Sydney Morning Herald photo department. One time I asked for some pictures from Vietnam and what they sent round was really shocking and graphic—US marines torturing Vietnamese people. This was the truth and, I mean, it just had to be printed. The other papers were never going to print anything so confronting. And unfortunately today, nothing much has changed.

So, after three years here, you moved to London and started Oz.

The decision was not so much to move to London as to leave Australia. The trials went on for a number of years until we were finally acquitted in 1965. There was jubilation, we were thrilled and I think at that point Australia was changed. Not from me individually or us as a group but something about Oz’s victory was definitely a step in Australia’s journey to a more open society. I know that sounds self-grandising but it really was a result of these civil libertarians working on our behalf to make Oz liberated—to ensure it wouldn’t be charged with obscenity and that obscenity could no longer be used as a battering ram to shut people up. However, I was incredibly exhausted.

We didn’t have a plan to start Oz in London, it was just a journey. We went via Asia and it was there on a train, somewhere in Cambodia or Laos, that we bought some marijuana. It was on this journey that we thought, ‘Well, I guess if there’s nothing else we can just start the magazine in London’. It was that simple.

What was the first issue in London?

It was quite straight really. We tackled religion, we satirised somebody we regarded as our competitor, Private Eye magazine, and strangely enough they were quite upset about it. That was a good story. There was a fold out photographic essay, a send up of the counter culture. Oz is so often seen as a kind of bible of the underground and youth culture but it also took the piss out of itself. I think that was quite an Australian characteristic and I think later on, as Oz got more colour, it became a bit psychedelic and in a way that was a manifestation of the Australian sunshine, the beaches and the liberating 60s surf culture.

I’m assuming Oz become more psychedelic as you started taking more drugs?

Well I was never particularly comfortable with drugs. In fact Timothy Leary had given this interview where he said ‘Turn on, Tune In, Drop Out’ and I was a bit horrified. One of the headlines in Oz, Number One I think, was ‘Turn On, Tune In, Drop Dead’, which I had written cause I was so shocked. But yes, people were definitely experimenting.

Oz was quite political but not necessarily aligned to any particular school.

We met a lot of people with all different politics. The thing about Oz is we had Trotskyists and Marxists and situationists, Aussies, surfies; it was a mixture. Coming to London and starting Oz I was pretty open minded to politics and issues. I was averse to the Liberal party and the Conservatives but I was open to all faiths and schisms of people who were part of the counter culture. And psychedelia gave us more curiosity about spiritual issues. So we weren’t trapped in a political straight jacket or the straight jacket of satire. But I was swept up in the politics of London, it was a much more political city than Sydney and I probably took myself a bit too seriously there for a while.

In hindsight do you think you actually believed in a lot of those things or were you just commenting on them?

We were ridiculous in a way. Look, we had changes and moods, just like everyone else and I think that we threw ourselves into the fray. And the fray at one stage could be incredible sympathy for the students in France in 68 who nearly overthrew the government, incredible sympathy for emerging gay culture, sympathy for cultural issues. Obviously with the alliance of Germaine Greer, Oz was very ahead of its time on feminism. There’s one issue of Oz known as the ‘Cunt Power’ issue, which was edited entirely by Germaine.

What did you tell your parents you were up to?

My father came to London once and took some issues back which were confiscated at customs. No one in Australia ever saw London Oz because even the subscription copies were stopped.

Still it must have been so exciting to be making that kind of impact?

Yeah, we were a strong group. There was lots of talk of a ‘downunderground’. But I was very fast moving in getting allies from the English and the Americans. We had Italians, French; it was a melange of people from all over the world. We were part of the Underground Press Syndicate so towards the end of the 60s, in my basement everyday, like a hundred underground magazines would come from all over the world. Oz was just one of hundreds of tabloid publications and we all shared content.

How do you feel about stuff you’ve written in the past now? Do you still agree with yourself?

Not always. I’m sometimes horrified by stuff I’ve read, sometimes I’m amused; sometimes I’m delightedly surprised. I’m sure I’ve been wrong about stuff and I’ve been right about stuff but it seems to me that I have an over-developed desire to enlarge the boundaries of communication. One of my heroes is Socrates and his credo was, “No God higher than truth”. I really think that whether you love it or hate it you have to have total freedom of speech cause that at least helps you to not only discover the truth but to play around with lots of plausible, possible truths.

We’re in the midst of a huge information revolution. There’s so much information out there, yet on the whole people are watching the mass media and don’t get that what they are seeing is actually a distorted and self-interested shard of the world. So in that regard, we still have room to blow people’s minds.

www.richardneville.com and www.homepagedaily.com

But then things started to change. People began thirsting for freedoms?

Yes but it happened very slowly. Even then, quite routinely, pop songs that had a sexual reference were banned from the radio.When television came in they started a show, Bandstand, to talk about the ‘new music’: rock n roll. It was actually shot live and hosted by a guy called Brian Henderson, who was well known in Australia at that time and later became the senior newsreader for Channel Nine.

Didn’t you kidnap him from the set?

Ha. Yes, that was pre Oz. God, this is so ancient. It was when I was editing the student paper Tharunka at university. I would have been in my very early 20s. The student council were looking for a stunt to raise money for a charity. I went along with a couple of bulky students and at a signal from me we grabbed Brian, put him in a car and drove him to a place up on the Northern beaches where a lot of other students were waiting and a huge party was going on with lots of booze. He’d never had so much fun in his life. We asked for a ransom and Channel Nine very quickly agreed to pay it. I think it was the happiest day of his life.

That could never happen now.

Probably not. Australian students by about 1961 were beginning to think there was something a bit too placid about Australia, there was injustice going on, there was censorship happening, a war was being fought and no one even had a clue why it was being fought. So they were starting to have a conversation about it.

For me the turning point was when an American comedian, Lenny Bruce, turned up in Australia to do a concert. He gave his first performance in Australia at a pub in Sydney and I couldn’t afford to go but I remember the next morning all the newspapers were headlined ‘Comedian Is Obscene At Performance’. And it was all cause he’d uttered a four-letter word on stage. I thought he was great so I tried to get him a show at the university but at the last minute the Vice-Chancellor intervened and said that Lenny Bruce wasn’t allowed on campus. I thought this is too much; enough is enough. And that was really the germ that led myself, and other less-self-promoting types, to start the magazine Oz.

Did you go to university with the other guys?

Richard Walsh, my co-editor, was one of the editors of Honi Soit, the Sydney University newspaper. Martin Sharp came to see me with a friend called Garry Shead, another painter, who is now incredibly highly priced, and they had just started a newspaper for art students called the Arty Wild Oat. From here, it all just fell into place.

So you launched and ended up in court not long after. What was the charge?

It was on infantile grounds. But now I’m going to have to make a confession, I hardly ever tell this story. But, because the parents and lawyers of some of the other editors were incredibly conservative, we were advised to plead guilty because it was assumed that we would be acquitted with no conviction recorded. And that’s what we did. We felt like it was the French Revolution all over again but when it came to court we were wearing suits and apologising and we got convicted anyway. That taught me a lesson. I’ve never pleaded guilty in my life again and never will.

I imagine the case broke a lot of new ground.

Yeah, and generally the issues of the magazine in question were radical, funny and beautifully illustrated by Martin. A lot of my tutors and professors at university even gave evidence on the grounds that we were in the public interest because the magazine had artistic and literary merit. Unfortunately the magistrate was incredibly biased so the trial ran on for a long time and eventually went all the way to high court. It went on for years but we were still able to publish other issues and Oz became a sort of megaphone of free speech for people in Australia.

What kind of topics did you tend to cover?

A really wide range—anything to do withpopular culture. We had incredible writers like Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer. There was a lot of Australian politics and certainly the war in Vietnam featured. We’d often get our pictures from the Sydney Morning Herald photo department. One time I asked for some pictures from Vietnam and what they sent round was really shocking and graphic—US marines torturing Vietnamese people. This was the truth and, I mean, it just had to be printed. The other papers were never going to print anything so confronting. And unfortunately today, nothing much has changed.

So, after three years here, you moved to London and started Oz.

The decision was not so much to move to London as to leave Australia. The trials went on for a number of years until we were finally acquitted in 1965. There was jubilation, we were thrilled and I think at that point Australia was changed. Not from me individually or us as a group but something about Oz’s victory was definitely a step in Australia’s journey to a more open society. I know that sounds self-grandising but it really was a result of these civil libertarians working on our behalf to make Oz liberated—to ensure it wouldn’t be charged with obscenity and that obscenity could no longer be used as a battering ram to shut people up. However, I was incredibly exhausted.

We didn’t have a plan to start Oz in London, it was just a journey. We went via Asia and it was there on a train, somewhere in Cambodia or Laos, that we bought some marijuana. It was on this journey that we thought, ‘Well, I guess if there’s nothing else we can just start the magazine in London’. It was that simple.

What was the first issue in London?

It was quite straight really. We tackled religion, we satirised somebody we regarded as our competitor, Private Eye magazine, and strangely enough they were quite upset about it. That was a good story. There was a fold out photographic essay, a send up of the counter culture. Oz is so often seen as a kind of bible of the underground and youth culture but it also took the piss out of itself. I think that was quite an Australian characteristic and I think later on, as Oz got more colour, it became a bit psychedelic and in a way that was a manifestation of the Australian sunshine, the beaches and the liberating 60s surf culture.

I’m assuming Oz become more psychedelic as you started taking more drugs?

Well I was never particularly comfortable with drugs. In fact Timothy Leary had given this interview where he said ‘Turn on, Tune In, Drop Out’ and I was a bit horrified. One of the headlines in Oz, Number One I think, was ‘Turn On, Tune In, Drop Dead’, which I had written cause I was so shocked. But yes, people were definitely experimenting.

Oz was quite political but not necessarily aligned to any particular school.

We met a lot of people with all different politics. The thing about Oz is we had Trotskyists and Marxists and situationists, Aussies, surfies; it was a mixture. Coming to London and starting Oz I was pretty open minded to politics and issues. I was averse to the Liberal party and the Conservatives but I was open to all faiths and schisms of people who were part of the counter culture. And psychedelia gave us more curiosity about spiritual issues. So we weren’t trapped in a political straight jacket or the straight jacket of satire. But I was swept up in the politics of London, it was a much more political city than Sydney and I probably took myself a bit too seriously there for a while.

In hindsight do you think you actually believed in a lot of those things or were you just commenting on them?

We were ridiculous in a way. Look, we had changes and moods, just like everyone else and I think that we threw ourselves into the fray. And the fray at one stage could be incredible sympathy for the students in France in 68 who nearly overthrew the government, incredible sympathy for emerging gay culture, sympathy for cultural issues. Obviously with the alliance of Germaine Greer, Oz was very ahead of its time on feminism. There’s one issue of Oz known as the ‘Cunt Power’ issue, which was edited entirely by Germaine.

What did you tell your parents you were up to?

My father came to London once and took some issues back which were confiscated at customs. No one in Australia ever saw London Oz because even the subscription copies were stopped.

Still it must have been so exciting to be making that kind of impact?

Yeah, we were a strong group. There was lots of talk of a ‘downunderground’. But I was very fast moving in getting allies from the English and the Americans. We had Italians, French; it was a melange of people from all over the world. We were part of the Underground Press Syndicate so towards the end of the 60s, in my basement everyday, like a hundred underground magazines would come from all over the world. Oz was just one of hundreds of tabloid publications and we all shared content.

How do you feel about stuff you’ve written in the past now? Do you still agree with yourself?

Not always. I’m sometimes horrified by stuff I’ve read, sometimes I’m amused; sometimes I’m delightedly surprised. I’m sure I’ve been wrong about stuff and I’ve been right about stuff but it seems to me that I have an over-developed desire to enlarge the boundaries of communication. One of my heroes is Socrates and his credo was, “No God higher than truth”. I really think that whether you love it or hate it you have to have total freedom of speech cause that at least helps you to not only discover the truth but to play around with lots of plausible, possible truths.

We’re in the midst of a huge information revolution. There’s so much information out there, yet on the whole people are watching the mass media and don’t get that what they are seeing is actually a distorted and self-interested shard of the world. So in that regard, we still have room to blow people’s minds.

www.richardneville.com and www.homepagedaily.com

Advertisement