Denver Art MuseumIn 1945, two years before Jackson Pollock made his first drip paintings, Grace Hartigan, 23, moved to New York City with Ike Muse, her art professor. Muse was there to advance his career in art. Hartigan was tagging along. One night, they threw a party. Muse had hung his paintings throughout the house. A solitary painting by Hartigan hung on the living-room wall. The guests pointed to it and congratulated Muse on his best painting yet. He was furious. He told Hartigan to stop painting. She didn't and eventually moved out.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The abstract expressionist movement, which attempted to free itself from figurative language, was largely dismissive of the work of these women, many of whom were accused of being too much in the shadow of more representational European traditions. A critic for ARTnews, writing in 1949 about both the work of Pollock and Krasner, said Krasner's paintings could be seen as an attempt to "tidy up" Pollock's more untamed gestures. Yet reading the show's catalog of the same name, published by Yale University Press, it's clear these artists approached painting with radical intuition. They, too, mined their subconscious for distinct styles, creating, as the curator, Gwen Chanzit, writes in her introduction, "painterly expressions brought on through direct or remembered experience": Frankenthaler with her dreamy color washes, DeFeo with her obsessive layering of paint, Hartigan with her vivid sense of scale, and experiments with the traditions of old masters.The strongest female figures of the period, refusing to be pitied, became remarkably tough survivors. They often did so not by rejecting the macho of the period, but by embracing it, showing the world that they could out-boy the boys… Joan Mitchell had a mouth that could shame a marine and could be especially cutting about other women. She called Helen Frankenthaler, who was known for staining her unprimed canvas with misty washes of paint, "that tampon painter."

Advertisement

Advertisement

StarzTo watch The Girlfriend Experience is to witness a young woman slowly destroying her life—or is it?The STARZ drama, executive-produced by Steven Soderbergh and very loosely adapted from his film of the same name, follows Christine Reade (Riley Keough), a 20-something second-year law student who lands an internship at Kirkland & Allen, a Chicago law firm. As the show progresses, she's drawn into the world of high-priced prostitution by a friend and fellow law student, Avery. Christine—who bangs under the nom de guerre Chelsea—has sex and intimate conversation (the girlfriend experience) with rich businessmen in sleek, antiseptic hotel rooms, making thousands of dollars a pop. It hardly seems like a spoiler to say these two lives intersect with disastrous consequences. But while the fallout clearly ruins the lives of many around Christine, its effect on her is more ambiguous—and it's also one of the most interesting aspects of the show.

Advertisement

David Daley

LiverightHow could Democrats win 1.4 million more votes than Republicans in 2012 and still lose the House by 33 seats? Welcome to modern politics in America. In his first book, Ratfucked (a term for political sabotage), David Daley, the editor in chief of Salon, shows how a few Republican operatives and dark-money donors were able to ensure legislative victories that could last through the decade, regardless of the popular vote. It began in 2010, when Republicans flooded local races with cash and took control of a handful of state legislatures, giving them the ability to draw local and congressional district lines that will last until 2022. Using software that compares everything from voters' political preferences to recent online purchases, they gerrymandered districts across the country, allowing them to guarantee Republican wins. But there's more at stake here than just party control, Daley argues. Gerrymandering creates districts so politically uniform that candidates only face a real threat in primaries, which are thought to attract more ideological voters than general elections. Daley believes this forces candidates from either party to become increasingly extreme in order to keep their seats, furthering political polarization. With the new battle to draw political lines approaching, Daley leaves readers wondering what the GOP is up to now. —SARAH MIMMS

Advertisement

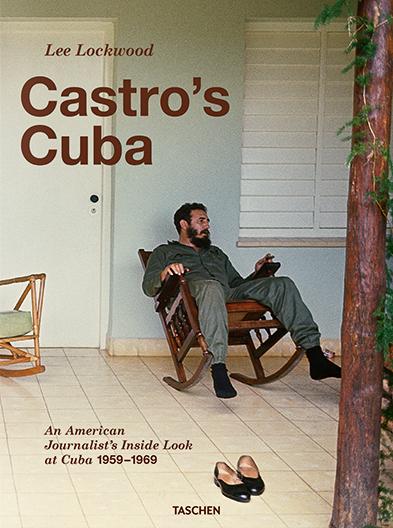

Lee Lockwood

TaschenIn 1965, six years after he covered the Cuban revolution, the photojournalist Lee Lockwood returned to document the country's new socialist system. He traveled with the young Fidel Castro around the country in jeeps, boats, and Soviet helicopters, photographing the charismatic leader giving speeches in tropical downpours, playing dominoes, and smoking cigars. Castro's Cuba—first published in 1967, and now reissued with more than 200 photographs from Lockwood's archives—is a diary of these fourteen weeks, accompanied by a transcript of a wide-ranging weeklong conversation he had with the then 39-year-old ruler. Some of Lockwood's photos are surprisingly intimate: a shirtless Fidel, in army pants and Chucks, flexing his muscles and doing pull-ups; in another shot, he lounges in a track suit, lazily pointing an AK-47 at something (or someone). Though he edited the interview before it was published, Castro welcomed Lockwood's pointed challenge to his utopian aims. He countered by accusing the US of hypocrisy over racial discrimination, money-clogged politics, and the suppression of Communist media. "An enemy of Socialism cannot write in our newspapers," he said to Lockwood. "We don't deny it, and we don't go around proclaiming a hypothetical freedom of the press where it actually doesn't exist, the way you people do." —NATALIE SHUTLER

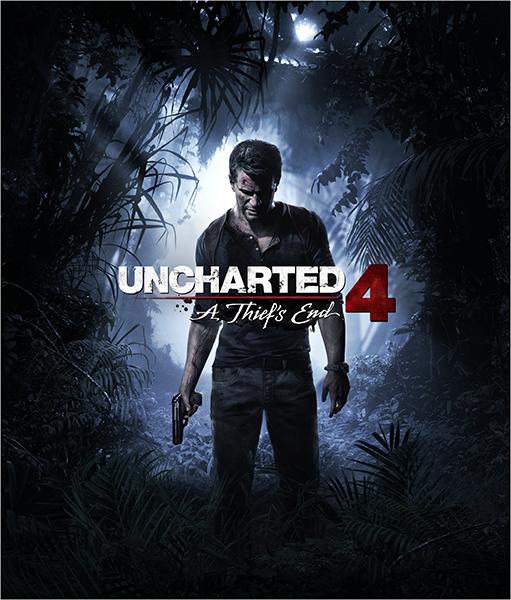

Naughty DogIn this final installment of the Uncharted series, Nathan Drake, the adventure seeker, treasure hunter, and amiable cypher, finds himself stuck, for once, in the mundanity of everyday life. He's married and working for a retrieval crew in New Orleans, when his seedy brother, Sam, shows up. Sam, sunken cheeked and sallow, is fresh from 15 years in a Panamanian jail, where Nathan inadvertently left him for dead after a treasure-hunting caper gone wrong. He's in deep with a Mexican drug lord and needs to find a payoff. Before long, the two are in search of a lost pirate treasure. The game is overwhelmingly beautiful, and the environments—17th-century abbeys, seaside Italian villas, lush tropical jungles—are rendered in almost stupefying detail. Yet for all its technological marvels, it feels old-fashioned. At heart, it's essentially an interactive summer blockbuster, part National Treasure, part Indiana Jones. The attempts to give characters more nuance and maturity are admirable, but there's an absurdity to watching Nathan bicker with his brother and wife about the give-and-take of adult relationships while being pursued by mercenaries through an abandoned pirate utopia on an island chain off the coast of Madagascar. —ROSCOE JONES

Ben Lerner

Farrar, Straus & Giroux"So many people have told me… they don't get poetry in general or my poetry in particular and/or believe poetry is dead," writes Ben Lerner in this slender but capacious new book. His response? "I, too, dislike it," he says, quoting the poet Marianne Moore. For Lerner, "disliking it" is reasonable because "like so many poets, I live in the space between what I am moved to do and what I can do." Sitting down to write means aspiring to achieve one's vision but knowing failure is the only option; sitting down to read a poem means encountering these yearnings and shortcomings. Ranging from Walt Whitman to Claudia Rankine, Lerner (himself a well-known poet and novelist) shows that poetry cannot do everything we want it to do—for example, "express irreducible individuality" or "defeat time"—but is "no less essential for being impossible." Poetry awakens the "desire for a measure of value that isn't 'calculative'"—and is all the more essential for reminding both writer and reader of the need for alternatives to dollars and utils, no matter how unattainable any alternatives may seem. —JULIAN GEWIRTZThese reviews appeared in the June issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.