Photo by Everett Kennedy Brown/EPA

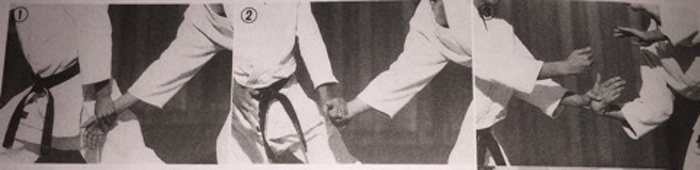

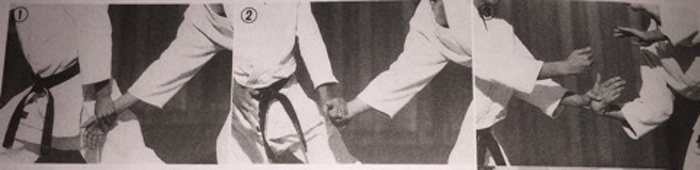

If you have grappled for any decent length of time you have experienced it: the guy who comes in with a little bit of experience in Aikido or classical Jujutsu. He's helpless on his back—as anyone who has never grappled before is, no shame there—but perhaps he drives a few ippon-ken thrusts into 'pressure poins' as you try to secure your pass. You think "fair enough" and introduce him to the Shoulder of Justice. You take the mount and get to work sneaking a hand into the collar when suddenly you find yourself on the receiving end of a wrist lock. With both hands on your attacking your would be collar grip, the aikidoka flexes your wrist towards you and then turns it violently to the outside and you tumble to bottom position. That centuries old staple of martial arts, the kote-gaeshi, strikes down yet another unsuspecting or even unbelieving victim. Except that has never, ever happened anywhere.If you have practiced any kind of traditional martial art you will be familiar with kote-gaeshi, the 'returning wrist' throw. Aikido legend, Gozo Shioda describes the technique in two movements: turning the wrist over and to the outside so that the elbow is bent inwards, and 'cutting down and over' with the other hand in order to unbalance him. Rather than a large, circular motion, Shioda advises that you try to contain the turning of the wrist in front of your stomach. The issue, of course, is that you are attempting to manipulate one of the opponent's hands with just one of your own. You are trying to force the opponent's shoulder, elbow and wrist into a weak alignment by pushing through a similar motion. You are not going to simply turn someone's hand over against their will from a static position and if you start moving your feet to make it easier, they are going to move theirs too. Furthermore, the correct grip to apply enough torque on the kote-gaeshi is with the thumb reaching all the way over to the knuckle of the opponent's little finger.

The issue, of course, is that you are attempting to manipulate one of the opponent's hands with just one of your own. You are trying to force the opponent's shoulder, elbow and wrist into a weak alignment by pushing through a similar motion. You are not going to simply turn someone's hand over against their will from a static position and if you start moving your feet to make it easier, they are going to move theirs too. Furthermore, the correct grip to apply enough torque on the kote-gaeshi is with the thumb reaching all the way over to the knuckle of the opponent's little finger. In effective wrist control, which is difficult enough to achieve, a grappler is creating a bracelet on the opponent and the opponent's hand—being wider than their wrist—cannot slide out as easily. To remove wrist control the opponent's hand must be held in place, or struck away, while the trapped wrist is cut or circled through the gap between the opponent's thumb and middle finger. Now look at the enormous gap between the thumb and fingers in the control above. Any decent grappler, when gripped at the wrist, punches off the grip and retracts their arm if at all possible. Reaching all the way around the hand itself for Kote-gaeshi gives very little actual control. When you factor in sweat it becomes a nightmare. When you factor in resistance and a trained opponent, it—like so much else in aikido—becomes impossible.At least, that is what this humble writer thought until downloading the career of the great Russian MMA pioneer, Volk Han. As a master of sambo, Han's RINGS career was full of dives for the opponent's legs and kani-basami leg scissors takedown attempts into leg attacks. Comparing Han's dives for the legs from everywhere with Garry Tonon's attempts at the same against Rousimar Palhares is an interesting exercise. While watching a match that Han had with Kiyoshi Timura, the two were trading slappy strikes when suddenly out of nowhere, Han hit the kote-gaeshi! Followed by an even tastier and more extravagant double wrist lock takeover.But the waters are muddied by the fact that Han took part in plenty of pro wrestling bouts which were shoots and a lot of MMA matches which were works. You never know where you stand with Volk Han. The whole thing seems too fantastic to be real, but equally he whips that wrist around to force Tamura over, something which you typically wouldn't do to someone you were co-operating with as it's pretty harsh on the wrist, elbow and shoulder.But then take this phenomenal piece of police work from China. A real world use of kote-gaeshi and a knife disarm all at once! You will notice that the officer uses a wide, swinging motion rather than the tight one Shioda prescribes and in fact steps behind the armed man to trip him. You will also notice that the 'perp' is distracted and holding his arm out and completely stationary… pretty weird. But then from behind and as part of a group is the only way that anyone should ever be thinking of confronting a man holding a big kitchen knife.Kazushi Sakuraba, in seminar footage shot at Chute Boxe some years ago, even demonstrated a true kote-gaeshi attempt from the guard as a means of getting the opponent to resist, before pulling the arm back across for the armbar. You will see some good guard players use the americana grip from guard in this way too.But kote-gaeshi from the feet might not be so unreasonable in the future. It is the practice against zombie charges and static lapel grips which stunts the development of practical applications of traditional techniques. Two-on-one wrist control is becoming a more common part of the clinch fight as fighters begin to create distance with their heads in order to infight. Jon Jones, for instance, frequently graduates to a two-on-one wrist control after establishing a chest to chest clinch. He is also one of the most creative fighters in the UFC so a kote-gaeshi against an opponent with their back to the fence isn't completely out of the question!

In effective wrist control, which is difficult enough to achieve, a grappler is creating a bracelet on the opponent and the opponent's hand—being wider than their wrist—cannot slide out as easily. To remove wrist control the opponent's hand must be held in place, or struck away, while the trapped wrist is cut or circled through the gap between the opponent's thumb and middle finger. Now look at the enormous gap between the thumb and fingers in the control above. Any decent grappler, when gripped at the wrist, punches off the grip and retracts their arm if at all possible. Reaching all the way around the hand itself for Kote-gaeshi gives very little actual control. When you factor in sweat it becomes a nightmare. When you factor in resistance and a trained opponent, it—like so much else in aikido—becomes impossible.At least, that is what this humble writer thought until downloading the career of the great Russian MMA pioneer, Volk Han. As a master of sambo, Han's RINGS career was full of dives for the opponent's legs and kani-basami leg scissors takedown attempts into leg attacks. Comparing Han's dives for the legs from everywhere with Garry Tonon's attempts at the same against Rousimar Palhares is an interesting exercise. While watching a match that Han had with Kiyoshi Timura, the two were trading slappy strikes when suddenly out of nowhere, Han hit the kote-gaeshi! Followed by an even tastier and more extravagant double wrist lock takeover.But the waters are muddied by the fact that Han took part in plenty of pro wrestling bouts which were shoots and a lot of MMA matches which were works. You never know where you stand with Volk Han. The whole thing seems too fantastic to be real, but equally he whips that wrist around to force Tamura over, something which you typically wouldn't do to someone you were co-operating with as it's pretty harsh on the wrist, elbow and shoulder.But then take this phenomenal piece of police work from China. A real world use of kote-gaeshi and a knife disarm all at once! You will notice that the officer uses a wide, swinging motion rather than the tight one Shioda prescribes and in fact steps behind the armed man to trip him. You will also notice that the 'perp' is distracted and holding his arm out and completely stationary… pretty weird. But then from behind and as part of a group is the only way that anyone should ever be thinking of confronting a man holding a big kitchen knife.Kazushi Sakuraba, in seminar footage shot at Chute Boxe some years ago, even demonstrated a true kote-gaeshi attempt from the guard as a means of getting the opponent to resist, before pulling the arm back across for the armbar. You will see some good guard players use the americana grip from guard in this way too.But kote-gaeshi from the feet might not be so unreasonable in the future. It is the practice against zombie charges and static lapel grips which stunts the development of practical applications of traditional techniques. Two-on-one wrist control is becoming a more common part of the clinch fight as fighters begin to create distance with their heads in order to infight. Jon Jones, for instance, frequently graduates to a two-on-one wrist control after establishing a chest to chest clinch. He is also one of the most creative fighters in the UFC so a kote-gaeshi against an opponent with their back to the fence isn't completely out of the question! Certainly Jones' overhook americana crank in the clinch against both Teixeira and Cormier, and Shinya Aoki's successful use of a winding armbar in MMA are very encouraging. Aoki's was a traditional, long distance standing joint lock set up from an orthodox, static clinch—performing a limp arm drag on his opponent's overhook—but in order to turn far enough ahead of his opponent to apply the lock Aoki had to be free on his feet. Nogueira used this same whizzer trap to sweep opponents from his half guard, but even with the exact same grips it would be almost impossible to apply the winding armlock against the mat due to the speed and mobility needed to stay ahead of the opponent's own turn.We give Aikido a lot of a flack in our Wushu Watch column, but there is still a part of me that regularly Googles 'kote-gaeshi street fight' and 'kote-gaeshi MMA'. There is still a part of me that wants to believe.Pick up Jack's new kindle book, Finding the Art, follow his new Podcast, or find him at his blog, Fights Gone By.

Certainly Jones' overhook americana crank in the clinch against both Teixeira and Cormier, and Shinya Aoki's successful use of a winding armbar in MMA are very encouraging. Aoki's was a traditional, long distance standing joint lock set up from an orthodox, static clinch—performing a limp arm drag on his opponent's overhook—but in order to turn far enough ahead of his opponent to apply the lock Aoki had to be free on his feet. Nogueira used this same whizzer trap to sweep opponents from his half guard, but even with the exact same grips it would be almost impossible to apply the winding armlock against the mat due to the speed and mobility needed to stay ahead of the opponent's own turn.We give Aikido a lot of a flack in our Wushu Watch column, but there is still a part of me that regularly Googles 'kote-gaeshi street fight' and 'kote-gaeshi MMA'. There is still a part of me that wants to believe.Pick up Jack's new kindle book, Finding the Art, follow his new Podcast, or find him at his blog, Fights Gone By.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

The case with kote-gaeshi seems to be that the principles and mechanics are sound, it is simply so difficult to apply against someone who is resisting to any degree. It could be the case that it is a technique which worked far better against the old fashioned wrist grabs which we imagine were commonplace in the days when the Japanese soldiering classes wore swords at their waist. Or it could be that the technique has always been practiced against unrealistically overcommitted lunges—but that is largely a phenomenon in Japanese ritualized martial arts and this same wrist attack can be found in Chinese manuals on chin na.Externally rotating the wrist and shoulder is a powerful method for unbalancing the opponent in theory, unfortunately footwork and grips make it unreliable in real competition. This is the same reason that you will never see the americana armlock used as a takedown—which is how it originated—but it is a powerful submission when the arm can be isolated against the mat. Similarly the 'returning wrist' can be useful in situations where the opponent's feet aren't free to move. Particularly from closed guard. Every time we discuss wrist locks and Aikido we have to mention Claudio Calasans because he is able to change the opponent's positioning with manipulation of their wrists just as Aikido does in principle on the feet.The straight forward armbar from the closed guard isn't common at the highest levels of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, it normally takes a bit more nuance to get there and no one is going to let you get their elbow to your center line before they start paying attention to what you're going to do with it. By attacking with wrist locks—as his opponent's hands are always going to be near enough to reach—Calasans can begin to break an opponent's posture and worm their elbow towards his centreline for a follow up armbar. The opponent does most of the work for him as they contort themselves in an attempt to resist the wrist lock. Both the hyper-flexed and hyper-extended wrist lock work beautifully as a double attack with the armbar for this reason.

Advertisement