When one thinks of swordsmanship, one typically thinks of the Japanese warrior, welding a katana, or perhaps a Celtic warrior swinging a broadsword. And empty-hand fighting is attributed to the British boxers or the French wrestlers. But in the Middle Ages, Germany surpassed itself as the European epicenter of knowledge in the martial arts. More than any other nation, Germanic martial artists wrote prodigiously on the subject of fighting arts, producing fencing manuals and other seminal texts that defined the German of Defence. As Europe slowly emerged from the dark, oppressive cocoon of the Medieval period, a renewed interest in science and reason sparked a revival, be it a very small one initially, in learning.This metamorphosis would eventually lead to the first codified fighting system in Europe. Although Germany military would remain in disorder until the mid-1700s and the rule of Frederick the Great, the German Masters of Defence cultivated a system of learning, and of language, that all Europeans could celebrate as the new scholarship of fighting.In ancient times, Germanic tribes passed down fighting styles by having their most experienced warrior teach the youth. Tribal communities lived in sects and the familial aspect of that culture made learning martial arts a social function, learned within the confines of the group. Training was based on the tribe's young men, and sometimes women, learning under the tutelage of the best warrior. Martial arts were taught in-person, and there are no written accounts as to how that training progressed, although there is some documentation as to the efficacy of Germanic warfare from the ancient Romans.Generations of this type of pedagogy by proximity forged a strong fighting culture, which continued even as political and military action altered the borders of the European landscape. In the Middle Ages, what had previously been the purview of individual warriors teaching random flocks of young men who might eventually become soldiers changed when Germanic fighting experts began to produce manuals describing their system of fighting arts. While the technology of writing was certainly not new to Germanic peoples by the Middle Ages, the subjects that were penned moved beyond religious and political dictates, and by the 13th century, German Masters of Defence began drafting some of the first martial arts textbooks in Europe.Of all of the European Masters of Defence from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance, the German masters were the most prolific writers of fighting arts from the mid-14th century to the early 16th century. Germany was also home to many fighting schools, called fechtschulen, where individuals could go to learn under the great masters and exercise—an early version of the German turnverein (gymnasium). Fighting schools were organized and operated by guilds like the Marxbruder, the Brotherhood of Saint Mark. Guilds were populated by soldiers and regular citizens, and specialized in particular weapons, such as the two-handed sword or the short knife.Fencing schools were not always considered socially acceptable in Germany. A 1464 engraving depicts a German fencing school and fitness center alongside of a brothel cum bath-house, indicating that to participate in martial arts training was to be involved in an activity lateral in morality to prostitution. Just 150 years later, at the end of the 16th century, Willem Swanenburg produced an engraving featuring a fencing school and instead of a chaotic depiction of debauchery, the school was organized, academic. Men appear to be practicing footwork and angles, and even doing a form on planking on the back of a horse.Germans in the Middle Ages may have enjoyed, or at least tolerated, fencing guilds, but they did not tolerate fools or pretenders to teach fighting arts. The Germans had no patience for charlatans, creating a clear lexical distinction between actual Masters and those who performed fighting as part of theater, the leichmeistrere (a snide reference to a dance-master) and the klopffechter, which translates to clown fighter.Interestingly, it is language and the creation of a fighting lexicon, that makes the German Masters of Defence such a fascinating study for fighting historians. The German Masters created a specific nomenclature for every move, and in fact, even named every opportunity in which one could attack. The nachraissen, attacking after, indicates the Germanic version of counter-punching in which a swordsman would invite an opponent to attack in order to follow up with a specific counter. The most famous of the German Masters, Johannes Lichtenauer, referred to these types of returns or after attacks the meisterhau, the masters cuts, and they became a central tenet of his style, and of the numerous Masters who followed in his footsteps and expanded his work. Johannes Lichtenauer, known usually as Hans, was the father of Germanic martial arts, the fechtmeister or fighting master of his time in the 1250s. In 1389, Hanko Döebringer, a priest who studied under Lichtenauer, compiled his master's work into a fencing manual, known as a fechterbuecher (fight book). Keeping with the fashion of the time, Döebringer wrote the entire treatise in rhyming couplets. Swedish linguist, David Lindholm, translated the work in 2005, and it provides insight into the German fighting art philosophy, which is, in essence, effective and to the point, without any unnecessary movements. While Masters of Defence in other countries may have practiced or even taught fighting suffused with style, the German master taught fighting without flourish. In the very beginning, Döebringer instructs that one should "strike or thrust in the shortest and nearest way possible" without any "wide or ungaingly parries."Liechtenauer's student and amanuensis, Hanko Döebringer, produced the text that, in 1389, would remain the foundation for German weapons fighting for the next three hundred years. He also instilled the notion of naming each particular movement with a specific name rather than trying to describe a technique by what it does. Although it may seem like it would be terribly confusing, it was easier, once conversant in Liechtenauer and other German Master's lexicon, to understand instructions using specific names like Zwerchhau meant side cut rather than to read "side cut" in conjunction with other instructions on footwork or movement.Döebringer's work on Lichtenauer's fighting methods included colorful and picturesque titles for his four primary stances. In his masterful historical round-up, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe, Sydney Anglo describes Liechtenauer's nomenclature and the stances they represented:Ochs (Ox) with sword held high and aimed down towards the opponent's face; Pflug (Plough) with sword held at waist level but also pointing up at the opponent's face; Alber (Fool) with sword held out in front, its point aimed at the ground; and vom Dach (from The Roof) with the sword held over the right shoulder and pointing upwards at about fourty-five degrees.As was mentioned in the previous article on Masters of Defence in Renaissance Italy, one problem that plagued all instructors was the transmission of information via the written word, known as la communicative. Ideally, one should train martial arts under the direct tutelage of a legitimate Master of Defence, but if there was no nearby instructor to be found, or if one wanted to study the works of a Master in another land, written treatises were available for the avid pupil willing to learn via text. The precise articulation of fighting techniques irked many Medieval and Renaissance era masters, but those who tackled the problem of enunciating their movements often employed artists or engravers to provide images to accompany their words, which helped in some cases. But not every manual proved to be a reliable or even effectual source of martial arts material. Many of the German treatises required the reader be aware of preexisting techniques and have knowledge of the clunky, if interesting, lexicon used by some masters.The expansion of Lichtenauer's methodologies culminated in an insanely dense and no doubt heavy text produced by Paulus Hector Mair in the mid-1500s. His prodigious work was overshadowed by his own misdeeds when Mair was hanged for embezzlement in 1579. But Mair's death did not mar the enthusiasm for fighting texts.

Johannes Lichtenauer, known usually as Hans, was the father of Germanic martial arts, the fechtmeister or fighting master of his time in the 1250s. In 1389, Hanko Döebringer, a priest who studied under Lichtenauer, compiled his master's work into a fencing manual, known as a fechterbuecher (fight book). Keeping with the fashion of the time, Döebringer wrote the entire treatise in rhyming couplets. Swedish linguist, David Lindholm, translated the work in 2005, and it provides insight into the German fighting art philosophy, which is, in essence, effective and to the point, without any unnecessary movements. While Masters of Defence in other countries may have practiced or even taught fighting suffused with style, the German master taught fighting without flourish. In the very beginning, Döebringer instructs that one should "strike or thrust in the shortest and nearest way possible" without any "wide or ungaingly parries."Liechtenauer's student and amanuensis, Hanko Döebringer, produced the text that, in 1389, would remain the foundation for German weapons fighting for the next three hundred years. He also instilled the notion of naming each particular movement with a specific name rather than trying to describe a technique by what it does. Although it may seem like it would be terribly confusing, it was easier, once conversant in Liechtenauer and other German Master's lexicon, to understand instructions using specific names like Zwerchhau meant side cut rather than to read "side cut" in conjunction with other instructions on footwork or movement.Döebringer's work on Lichtenauer's fighting methods included colorful and picturesque titles for his four primary stances. In his masterful historical round-up, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe, Sydney Anglo describes Liechtenauer's nomenclature and the stances they represented:Ochs (Ox) with sword held high and aimed down towards the opponent's face; Pflug (Plough) with sword held at waist level but also pointing up at the opponent's face; Alber (Fool) with sword held out in front, its point aimed at the ground; and vom Dach (from The Roof) with the sword held over the right shoulder and pointing upwards at about fourty-five degrees.As was mentioned in the previous article on Masters of Defence in Renaissance Italy, one problem that plagued all instructors was the transmission of information via the written word, known as la communicative. Ideally, one should train martial arts under the direct tutelage of a legitimate Master of Defence, but if there was no nearby instructor to be found, or if one wanted to study the works of a Master in another land, written treatises were available for the avid pupil willing to learn via text. The precise articulation of fighting techniques irked many Medieval and Renaissance era masters, but those who tackled the problem of enunciating their movements often employed artists or engravers to provide images to accompany their words, which helped in some cases. But not every manual proved to be a reliable or even effectual source of martial arts material. Many of the German treatises required the reader be aware of preexisting techniques and have knowledge of the clunky, if interesting, lexicon used by some masters.The expansion of Lichtenauer's methodologies culminated in an insanely dense and no doubt heavy text produced by Paulus Hector Mair in the mid-1500s. His prodigious work was overshadowed by his own misdeeds when Mair was hanged for embezzlement in 1579. But Mair's death did not mar the enthusiasm for fighting texts. Like Italian Master Pietro Monte, German fencing masters regarded wrestling as foundational to all fighting arts. Indeed, the German Masters provided some of the only empty-hand fighting treatises to be published in the Middle Ages. One manuscript, Ringen im Grüblein, (Wrestling in the Little Pit) describes a wrestling sport that required one opponent to keep a foot in a small, shallow hole while his opponent, who had to hop on one fit, apparently as a way to even the playing field, attempted to force him out—literally wrestling in a pit. According to Fabian von Auerswald, medieval wrestling master, "it calls for great skill, and is enjoyable to watch."Von Auerswald produced his own manual in 1539, and described wrestling as a sport rather than an approach to combat. In describing one particular maneuver that sounds similar to an arm-drag, he explained that it could produce a "terrible dislocation" which, while effective, was "something for rough folk and is not convivial." Yet Von Auerswald also offered readers a technique in which one grabs an opponent "between the cheeks of his arse" or wrenches the testicles. Perhaps it was these techniques that, while not 'convivial' by our standards, did allow Von Auerswald, depicted in his text as a rather wrinkled old man, to easily best his younger, seemingly-debilitated opponent. While wrestling at the time seemed to strive for sport, other Masters included techniques that were more lethal combat maneuvers. Christian Egenolff's 1531 treatise, Der altenn Fechter, contains instructions for head-butting, strangle holds, and a 'back-breaker.'

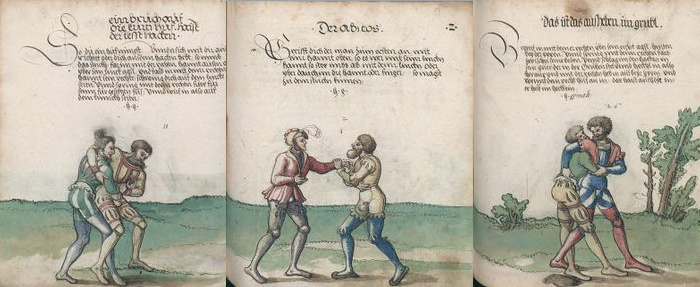

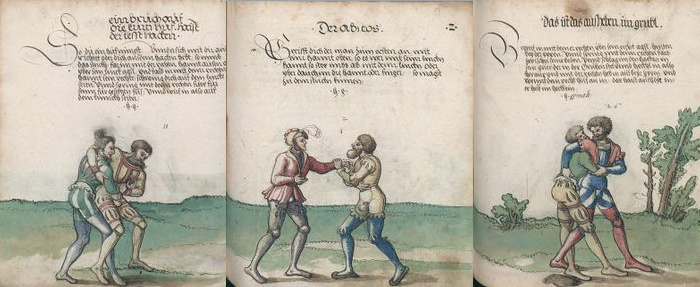

Like Italian Master Pietro Monte, German fencing masters regarded wrestling as foundational to all fighting arts. Indeed, the German Masters provided some of the only empty-hand fighting treatises to be published in the Middle Ages. One manuscript, Ringen im Grüblein, (Wrestling in the Little Pit) describes a wrestling sport that required one opponent to keep a foot in a small, shallow hole while his opponent, who had to hop on one fit, apparently as a way to even the playing field, attempted to force him out—literally wrestling in a pit. According to Fabian von Auerswald, medieval wrestling master, "it calls for great skill, and is enjoyable to watch."Von Auerswald produced his own manual in 1539, and described wrestling as a sport rather than an approach to combat. In describing one particular maneuver that sounds similar to an arm-drag, he explained that it could produce a "terrible dislocation" which, while effective, was "something for rough folk and is not convivial." Yet Von Auerswald also offered readers a technique in which one grabs an opponent "between the cheeks of his arse" or wrenches the testicles. Perhaps it was these techniques that, while not 'convivial' by our standards, did allow Von Auerswald, depicted in his text as a rather wrinkled old man, to easily best his younger, seemingly-debilitated opponent. While wrestling at the time seemed to strive for sport, other Masters included techniques that were more lethal combat maneuvers. Christian Egenolff's 1531 treatise, Der altenn Fechter, contains instructions for head-butting, strangle holds, and a 'back-breaker.' The most famous wrestling treatise to emerge from the Renaissance was Nicolaes Petter and Romein de Hooghe's 1674 text, The Academy of the admirable Art of Wrestling. This text offered "clear and homely instruction" on the ways in which a fighter can, with his newfound knowledge of the human body, provided by the text, avoid any attack using wrestling methodologies Petter and Hooghe's methods, however, appear to largely be reiterations of the works of those masters who came before them, but it was the articulation, the very clear language and wonderfully illustrated engravings, that made this book the apotheosis of German wrestling instruction.Petter, a wine merchant and wrestling aficionado, reportedly died in 1672. His wife doggedly pushed to publish his text, and with the help of de Hooghe, an engraver of the first water, Petter's treatise was released just two years after his death. The techniques include a variation of holds and throws, including a particularly brutal maneuver which can be described only as a hair throw. Petter relied on letters for naming the participants in a certain technique. In this example, the first man, D, secures his grips by grabbing the hair of his opponent, E, in his fingers, then twisting his elbows inward so that they are parallel and inside of E's arms."Then D pulls E backwards by the hair, turning him around, placing his elbow on his spine, which allows him to strike E on the face from behind with his other hand.

The most famous wrestling treatise to emerge from the Renaissance was Nicolaes Petter and Romein de Hooghe's 1674 text, The Academy of the admirable Art of Wrestling. This text offered "clear and homely instruction" on the ways in which a fighter can, with his newfound knowledge of the human body, provided by the text, avoid any attack using wrestling methodologies Petter and Hooghe's methods, however, appear to largely be reiterations of the works of those masters who came before them, but it was the articulation, the very clear language and wonderfully illustrated engravings, that made this book the apotheosis of German wrestling instruction.Petter, a wine merchant and wrestling aficionado, reportedly died in 1672. His wife doggedly pushed to publish his text, and with the help of de Hooghe, an engraver of the first water, Petter's treatise was released just two years after his death. The techniques include a variation of holds and throws, including a particularly brutal maneuver which can be described only as a hair throw. Petter relied on letters for naming the participants in a certain technique. In this example, the first man, D, secures his grips by grabbing the hair of his opponent, E, in his fingers, then twisting his elbows inward so that they are parallel and inside of E's arms."Then D pulls E backwards by the hair, turning him around, placing his elbow on his spine, which allows him to strike E on the face from behind with his other hand. E being inconvenienced thus, still being held by the hair, D turns around so that D and E are back to back, D then places his behind against the behind of E, and pulls him with great force, as a result of which E will fall over the head of D."In this somewhat convoluted maneuver, D ends up throwing E by his hair, yet E is not vanquished, despite this painful insult. According to the plates, E leaps up and "grasps D behind the sleeve or arm, and grasps with the right hand the right wrist of D, forcing this grasped arm of D inwards, and places his left foot on the back of the right knee of D, thus forcing him to fall."Petter's methodologies vacillate from their appropriateness for sport to deadlier techniques against knife-wielding opponents. Many of his wrestling approaches include mention of making good sport and are obviously meant for wrestling contests. He does take a more serious approach to providing explanations of what to do when an unarmed man encounters a man with a knife. One engraving shows the unarmed man stepping on his opponent's foot and simultaneously punching him in the face, apparently as a method of disarmament. He also provides techniques to break the hand holding a blade, a disarming method that makes the holder stab himself, as well as a maneuver that seems straight out of Hollywood where one kicks the knife out of the hand of the bumbling, would-be assassin.Many of these maneuvers are seemingly impossible to deploy, at least to one relatively experienced in the actuality of blade-fighting, yet others seem perfectly probably. Despite whether or not Petter was the greatest Master of Defence in Germany, his tome provided martial arts enthusiasts, both contemporary to his time and modern, with wrestling tactics that were often ignored, distained, or neglected in an age dedicated to rapier and sword fighting.Between the 13th and 17th centuries, German Masters expanded on both Petter's and Liechtenauer's techniques by including other types of weapons and fighting methodologies, generating a massive glossary of terms and essentially, creating a new language in which an utterance was inextricable from the action. The individual lexemes, put forth to clarify the often advanced movements required to avoid the thrust of a rapier, or sidestep out of an arm lock, combined to form a Defence dictionary, and a system of fighting that was both word and action. It was the ultimate signifier/signified relationship – a system of signification that would titillate even the driest of semiologists, and pave the way for the language used by Catch-as-Catch-Can wrestlers or Brazilian jiu jitsu practitioners centuries later.

E being inconvenienced thus, still being held by the hair, D turns around so that D and E are back to back, D then places his behind against the behind of E, and pulls him with great force, as a result of which E will fall over the head of D."In this somewhat convoluted maneuver, D ends up throwing E by his hair, yet E is not vanquished, despite this painful insult. According to the plates, E leaps up and "grasps D behind the sleeve or arm, and grasps with the right hand the right wrist of D, forcing this grasped arm of D inwards, and places his left foot on the back of the right knee of D, thus forcing him to fall."Petter's methodologies vacillate from their appropriateness for sport to deadlier techniques against knife-wielding opponents. Many of his wrestling approaches include mention of making good sport and are obviously meant for wrestling contests. He does take a more serious approach to providing explanations of what to do when an unarmed man encounters a man with a knife. One engraving shows the unarmed man stepping on his opponent's foot and simultaneously punching him in the face, apparently as a method of disarmament. He also provides techniques to break the hand holding a blade, a disarming method that makes the holder stab himself, as well as a maneuver that seems straight out of Hollywood where one kicks the knife out of the hand of the bumbling, would-be assassin.Many of these maneuvers are seemingly impossible to deploy, at least to one relatively experienced in the actuality of blade-fighting, yet others seem perfectly probably. Despite whether or not Petter was the greatest Master of Defence in Germany, his tome provided martial arts enthusiasts, both contemporary to his time and modern, with wrestling tactics that were often ignored, distained, or neglected in an age dedicated to rapier and sword fighting.Between the 13th and 17th centuries, German Masters expanded on both Petter's and Liechtenauer's techniques by including other types of weapons and fighting methodologies, generating a massive glossary of terms and essentially, creating a new language in which an utterance was inextricable from the action. The individual lexemes, put forth to clarify the often advanced movements required to avoid the thrust of a rapier, or sidestep out of an arm lock, combined to form a Defence dictionary, and a system of fighting that was both word and action. It was the ultimate signifier/signified relationship – a system of signification that would titillate even the driest of semiologists, and pave the way for the language used by Catch-as-Catch-Can wrestlers or Brazilian jiu jitsu practitioners centuries later.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement