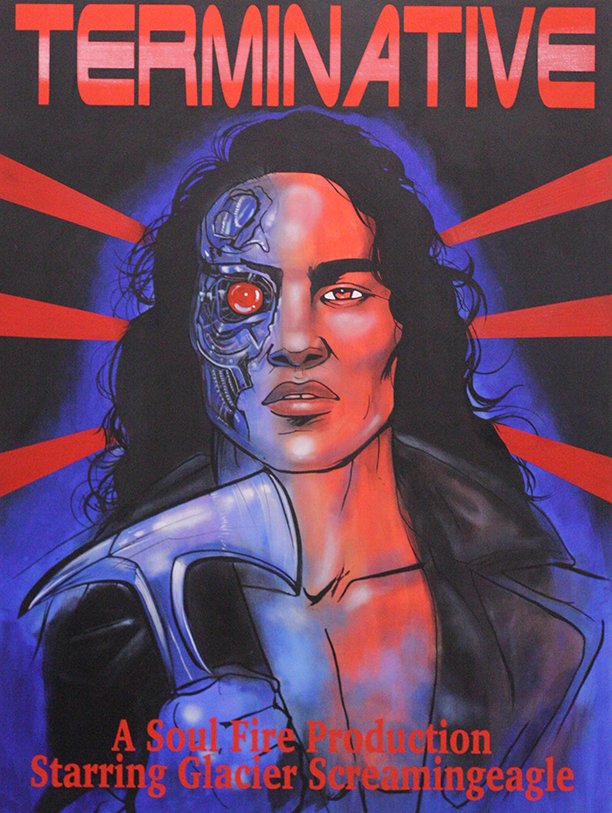

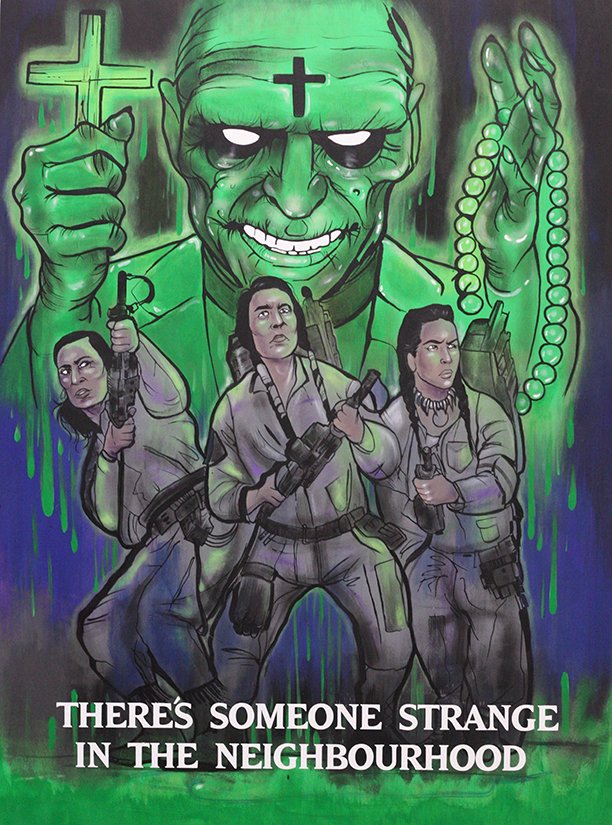

All art courtesy Chippewar

Toronto Indigenous multimedia artist Jay Soule is no stranger to doing things himself. His grassroots work can be seen across the city, from a piece on a concrete planter on Queen West to his sticker designs dotting light posts across downtown. While Canada 150 celebrations forwarded narratives and imagery that appropriated and erased Indigenous identities in Canada, Soule has been fighting for representation, autonomy, and decolonization with a mix of activism and art.Soule works under the name Chippewar (a nod to both his identity as a Chippewa of the Thames and the ongoing hostility his community endures), and with his recent movie poster series, he's Indigenizing and reclaiming pop culture imagery and narratives. By inserting Indigenous identities into iconic movie posters, he highlights both the necessity for, and staggering lack of, representation of Indigenous identities in the arts.This art confronts us with the fact that until Indigenous people are restored full agency over their representation and narrative, any use of their identities and culture by non-Indigenous people will function as an appropriative tool of colonialism and erasure. Soule is creating art that resists that structure, and reclaims narrative power.VICE: When did you start doing visual art?

Chippewar: I started painting about five years ago. Being in the tattoo industry the last 16 years, I've always been involved in art, and design and tattoo work. I just kind of crossed over from tattooing into pursuing visual arts full time.Was there anything that prompted that shift?

It was actually during a little break I was taking. The beginning of the Idle No More movement kind of set that off for me. During that same time, there was the election for the [Assembly of First Nations] National Chief. I was just watching that whole process, and it sort of woke me up a little bit to Indigenous issues in Canada. It made me think, 'Okay, if I'm gonna do visual art, who will I be known as and what will my work look like?' So from the start, it sounds like there was an element of resistance to your work.

So from the start, it sounds like there was an element of resistance to your work.

Absolutely, just because of how it was born. When that spark woke me up, the very first pieces I designed were, I guess you would call resistance art. Not necessarily resistance art, but I guess telling the story of struggle and resistance.Your movie poster series is really brilliant. I wanted to get an idea of where it came from.

When I had started painting I was doing group shows, and one of the galleries I was working with would always do these theme shows. From a monster series show, or a carnival series show, or a Candyland-themed show, and I was like 'Okay, how do I take a monster theme and make it Indigenous?' and so on. I liked the challenge of that. It was interesting to not present the expected, and so I would take those themes and give it a twist of some kind.It seems that it recontextualizes things that we've ostensibly grown up consuming and identifying with, so it immediately prompts a reaction in viewers. Is there ever concern that people will miss the message that you're trying to get across?

At first when I did these, I wasn't trying to do any sort of message. The series before these were the 1940s-50s movie monsters. I love horror movies, I love cinema, and I thought it'd be really rad to see Frankenstein as native. So at first when I did that series, it was more about doing some rad artwork: bright colours and changing up the imagery to Indigenous characters. The Hollywood Indian has always been portrayed as the monster, as the filthy, uneducated savage man. Even to this day, Indigenous people are stereotyped through film.It was also about reclaiming Indigenous identity, and what Hollywood could look like with inclusion rather than us being told what we look like.It seems like it prompts not just the issue of representation, but the issue of being in control of that representation.

Absolutely. By doing that, it just shows that with us in control of our stories and our image, we're gonna present something probably completely different than how the Hollywood Indian has been presented.I was accused of cultural appropriation of Western culture, which is insane. What I'm doing is I'm taking pop culture, which is for everybody, and I'm Indigenizing it. I'm also putting a spotlight on cultural appropriation and how, through Hollywood and through the entertainment and arts industry, our work and our identities have been appropriated. The fact that people suggest that argument betrays a basic collective lack of understanding about what cultural appropriation is.

The fact that people suggest that argument betrays a basic collective lack of understanding about what cultural appropriation is.

I got probably 30-40 pieces of hate mail. A few people between that were more inquisitive about asking, 'Where am I missing it? What don't I understand?' And at the end of the day, it's not my job to educate people. If you really care about it and really want to know, do it yourself. Don't insult me and then expect me to engage with you.People have also discussed whether it's appropriative for non-Indigenous people to wear your shirts and art. You don't think that's the case, right?

I don't think so. It's wrong when it's our artwork and our identities being stolen for profit. When you're buying it from an Indigenous source, you're supporting my artwork, you're supporting my business, you're supporting my living, and you're buying it because you respect it. When you go and buy from a large conglomerate brand and [there's] no Indigenous connection, it's just exploiting imagery. Don't support that, and if you see it, speak out about it.It strikes me that the role of visual art in resistance movements is so important. What role does art play in resistance for you?

One of my mentors was like, 'Art and politics don't mix. Leave it alone.' His work was completely fine art. For someone like him, maybe, but for me, and a lot of artists, there's definitely a connection through storytelling and resistance. It's the best way to portray struggle, is through imagery. Most people won't take the time to read a whole article about something, but they can look at a picture and see a small blurb below it and see the connection through the imagery. That little paragraph can really wake your brain up to a lot of things that maybe you wouldn't think about. It's a way to shorten that view and close it in.I saw a lot of friends celebrating non-Indigenous people for discussing Indigenous issues in Canada, and it really struck me that that's just forwarding erasure because it's erasing Indigenous voices.

Absolutely. From my perspective, Gord Downie, Joseph Boyden, [and Justin] Trudeau are put into the spotlight to control the narrative, and the narrative that's being controlled is, 'Let's talk about residential schools.' From my perspective, it's wrong. A lot of our identity has been lost because of residential schools, but at the same time, the fallout from it isn't just that. The fall out is so many major issues that are happening today. Stop beating a dead horse. Let's talk about the missing and murdered [women], let's talk about the mass incarceration, the poverty rates, the third-world conditions, the suicides, clean drinking water, food security, housing. All of those things are happening today.The [Truth And Reconciliation Commission] report and recommendations have been written from a colonial perspective, not from a grassroots Indigenous perspective. It's a giant PR campaign. You hear Murray Sinclair say, 'This is gonna take 20-30 years to implement.' We don't have 20-30 years. This stuff is happening now.That's something that comes through in your art: until Indigenous people have full autonomy and agency over their narrative and representation, the mechanisms that are put in place are ultimately still tools of colonialism.

Canada has adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but they haven't implemented it. A good example is cultural appropriation. Canada is guilty of cultural appropriation through Parks Canada, through Tourism Canada, through supporting national galleries that hold stolen artifacts, that own stolen bones of deceased ancestors. For them to correct their behaviour, it means they would have to give all of that stuff back. You go to any Parks Canada park, and inside their gift shop, they have culturally appropriated artwork, whether its paintings, beadwork, moccasins, dream catchers, little kitschy, shitty little trinkets. That directly hurts the economy of Indigenous people. In order for Canada to be able to adopt [the Declaration], they have to remove all of those things from their shelves. Something like 70 percent of Indigenous people in Canada support themselves through the arts, and that's a very broad spectrum of arts. If Canada enforced [the Declaration], it would really help our communities.A new campaign I've started is to do that. It's a site I'm launching with a gallery owner in Montreal, and it's called ReclaimIndigenousArts.com. You can go to the website, it's got a brief description of what cultural appropriation is, how it hurts, who you're hurting, the economics behind it, and then the PDFs that you'll print off is one goes to Tourism Canada, and it's, 'Let Tourism Canada know to stop using us as your token indians.' So for you, if you wanna support this, we want you to go onto the website, we want you to print off the PDF, we want you to date it and sign it and send it in. The idea behind that is to put Parks Canada on check, to put Tourism Canada on check. Stop using us as your token indians, as your mascots, to promote Canada.Also included in the site will be a database full of Indigenous artists. If these people wanna buy direct from Indigenous artists, that's where they can go. If you really care about reconciliation, if you really want to have that relationship, here's how you do it. Support our artists. If reconciliation is real, put your money where your mouth is, and support our largest independent economy, which is arts.Follow Luke on Twitter.

Advertisement

Chippewar: I started painting about five years ago. Being in the tattoo industry the last 16 years, I've always been involved in art, and design and tattoo work. I just kind of crossed over from tattooing into pursuing visual arts full time.Was there anything that prompted that shift?

It was actually during a little break I was taking. The beginning of the Idle No More movement kind of set that off for me. During that same time, there was the election for the [Assembly of First Nations] National Chief. I was just watching that whole process, and it sort of woke me up a little bit to Indigenous issues in Canada. It made me think, 'Okay, if I'm gonna do visual art, who will I be known as and what will my work look like?'

Advertisement

Absolutely, just because of how it was born. When that spark woke me up, the very first pieces I designed were, I guess you would call resistance art. Not necessarily resistance art, but I guess telling the story of struggle and resistance.Your movie poster series is really brilliant. I wanted to get an idea of where it came from.

When I had started painting I was doing group shows, and one of the galleries I was working with would always do these theme shows. From a monster series show, or a carnival series show, or a Candyland-themed show, and I was like 'Okay, how do I take a monster theme and make it Indigenous?' and so on. I liked the challenge of that. It was interesting to not present the expected, and so I would take those themes and give it a twist of some kind.It seems that it recontextualizes things that we've ostensibly grown up consuming and identifying with, so it immediately prompts a reaction in viewers. Is there ever concern that people will miss the message that you're trying to get across?

At first when I did these, I wasn't trying to do any sort of message. The series before these were the 1940s-50s movie monsters. I love horror movies, I love cinema, and I thought it'd be really rad to see Frankenstein as native. So at first when I did that series, it was more about doing some rad artwork: bright colours and changing up the imagery to Indigenous characters. The Hollywood Indian has always been portrayed as the monster, as the filthy, uneducated savage man. Even to this day, Indigenous people are stereotyped through film.

Advertisement

Absolutely. By doing that, it just shows that with us in control of our stories and our image, we're gonna present something probably completely different than how the Hollywood Indian has been presented.I was accused of cultural appropriation of Western culture, which is insane. What I'm doing is I'm taking pop culture, which is for everybody, and I'm Indigenizing it. I'm also putting a spotlight on cultural appropriation and how, through Hollywood and through the entertainment and arts industry, our work and our identities have been appropriated.

I got probably 30-40 pieces of hate mail. A few people between that were more inquisitive about asking, 'Where am I missing it? What don't I understand?' And at the end of the day, it's not my job to educate people. If you really care about it and really want to know, do it yourself. Don't insult me and then expect me to engage with you.People have also discussed whether it's appropriative for non-Indigenous people to wear your shirts and art. You don't think that's the case, right?

I don't think so. It's wrong when it's our artwork and our identities being stolen for profit. When you're buying it from an Indigenous source, you're supporting my artwork, you're supporting my business, you're supporting my living, and you're buying it because you respect it. When you go and buy from a large conglomerate brand and [there's] no Indigenous connection, it's just exploiting imagery. Don't support that, and if you see it, speak out about it.

Advertisement

One of my mentors was like, 'Art and politics don't mix. Leave it alone.' His work was completely fine art. For someone like him, maybe, but for me, and a lot of artists, there's definitely a connection through storytelling and resistance. It's the best way to portray struggle, is through imagery. Most people won't take the time to read a whole article about something, but they can look at a picture and see a small blurb below it and see the connection through the imagery. That little paragraph can really wake your brain up to a lot of things that maybe you wouldn't think about. It's a way to shorten that view and close it in.I saw a lot of friends celebrating non-Indigenous people for discussing Indigenous issues in Canada, and it really struck me that that's just forwarding erasure because it's erasing Indigenous voices.

Absolutely. From my perspective, Gord Downie, Joseph Boyden, [and Justin] Trudeau are put into the spotlight to control the narrative, and the narrative that's being controlled is, 'Let's talk about residential schools.' From my perspective, it's wrong. A lot of our identity has been lost because of residential schools, but at the same time, the fallout from it isn't just that. The fall out is so many major issues that are happening today. Stop beating a dead horse. Let's talk about the missing and murdered [women], let's talk about the mass incarceration, the poverty rates, the third-world conditions, the suicides, clean drinking water, food security, housing. All of those things are happening today.

Advertisement

Canada has adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but they haven't implemented it. A good example is cultural appropriation. Canada is guilty of cultural appropriation through Parks Canada, through Tourism Canada, through supporting national galleries that hold stolen artifacts, that own stolen bones of deceased ancestors. For them to correct their behaviour, it means they would have to give all of that stuff back. You go to any Parks Canada park, and inside their gift shop, they have culturally appropriated artwork, whether its paintings, beadwork, moccasins, dream catchers, little kitschy, shitty little trinkets. That directly hurts the economy of Indigenous people. In order for Canada to be able to adopt [the Declaration], they have to remove all of those things from their shelves. Something like 70 percent of Indigenous people in Canada support themselves through the arts, and that's a very broad spectrum of arts. If Canada enforced [the Declaration], it would really help our communities.A new campaign I've started is to do that. It's a site I'm launching with a gallery owner in Montreal, and it's called ReclaimIndigenousArts.com. You can go to the website, it's got a brief description of what cultural appropriation is, how it hurts, who you're hurting, the economics behind it, and then the PDFs that you'll print off is one goes to Tourism Canada, and it's, 'Let Tourism Canada know to stop using us as your token indians.' So for you, if you wanna support this, we want you to go onto the website, we want you to print off the PDF, we want you to date it and sign it and send it in. The idea behind that is to put Parks Canada on check, to put Tourism Canada on check. Stop using us as your token indians, as your mascots, to promote Canada.Also included in the site will be a database full of Indigenous artists. If these people wanna buy direct from Indigenous artists, that's where they can go. If you really care about reconciliation, if you really want to have that relationship, here's how you do it. Support our artists. If reconciliation is real, put your money where your mouth is, and support our largest independent economy, which is arts.Follow Luke on Twitter.