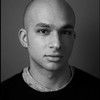

Joshua Williams at a 2014 Ferguson, Missouri city council meeting. Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

It's been three years since police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed an unarmed teenager named Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The protests against the Ferguson police that followed helped propel the already-burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement, and drew widespread awareness to the militarization of American law enforcement. But it also took a toll on the activists involved. For Joshua Williams, it took eight years of his life.Williams, one of the more prominent activists in Ferguson before being taken into custody, was arrested in December 2014 for setting a fire outside a QuikTrip convenience store during a heated protest. His actions caused almost no damage, yet after pleading guilty to arson, burglary and theft charges, Williams was ultimately sentenced to eight years in prison—a longer sentence than others received for similar or worse crimes, as Huffington Post pointed out. Williams and other Ferguson activists say his long sentence is an attempt to scare other protesters."I was surprised by the sentence," Williams told me over the phone from the Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in rural Missouri. "For someone who hasn't committed any crimes in his life, who hasn't been in juvenile, the sentence doesn't fit the crime. I think they wanted to make an example out of me."Williams was 19 when he felt called to action in Ferguson. He said he was politically aware before then, but Michael Brown's killing galvanized him. He began taking police violence more seriously, and realized his friends' lives could be on the line. Following Brown's death, he said he took to protesting nearly every week.After a falling out with his mom over his activism (she was worried about his safety), Williams began staying with friends and fellow activists in Ferguson. Then Antonio Martin, another black teen who lived just a few miles from Williams, was killed in December of 2014, and tension in the city grew."I was angry," Williams told me. "In my mind, nobody was listening to us. Every time we go out they act like they're going to change things, but they don't, and they won't, until something affects their money and their system. That's when they respond."On December 24, 2014, in the heat of a protest, Williams followed a group who had broken into a QuikTrip convenience store. He decided to use lighter fluid to set a fire to a garbage can outside the store. It was put out before causing damage, but police investigated the incident, and two days later, as he was walking to a Christmas party, cops surrounded and arrested him. He spent nearly a year in jail before his trial. The following December, a judge sentenced Williams to eight years for arson, a sentence that he and his supporters say grossly outweighs his crime."The police were the ones tear-gassing us, beating us, calling us monkeys," Maria Chappelle-Nadal, a prominent protester in Ferguson and a Missouri state senator said. "To know that and to know Josh and what kind of person he is—it's just unfair."

Watch Thomas Morton head to Ferguson, Missouri at the height of the historic protests there:

Williams is about two years into his eight-year sentence. He said he occupies his time by reading the Bible, talking on the phone with his mom and other activists, and trying to learn more about his case."It's pretty nerve-wracking in here," he said. "A lot of people recognize me. Some corrections officers are racist. Some call me 'QuikTrip.' Some ask if I have a lighter."Williams told me that he gets unfairly treated by guards in the prison because they see his actions in Ferguson as anti-police. A few weeks ago, Williams said he was helping move a medical patient in a wheelchair who was having an asthma attack through the prison. After taking a wrong turn, a guard wrote him up—with a two month stint in solitary confinement as punishment. The only break Williams got during those two months from his small, square room was to talk to me over the phone in another section of the prison.Williams passed most of his time in solitary talking to himself and reading (The Grave Tattoo, by Val McDermid, a thriller, was his favorite). He wasn't allowed to wear clothes, just boxers. He said he felt dehumanized, but managed to keep himself feeling sane throughout. Extended periods of solitary confinement have been shown to cause rapid deteriorations in people's emotional states. "I try to keep myself from going into that state of mind," he said. "I know I'm strong enough to do this."Williams would repeat Psalm 91 ("Whoever dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty") to himself over and over again to ward off boredom and depression."I'm in this dark place right now," he said. "And I know God is there with me, and he'll get me through."But even when he's out of solitary, Williams lives in fear of reprisals from guards. He said they'll write him up for anything, even having one section of his shirt untucked.He's also at risk because other prisoners know his story, and know he has support from activists on the outside. They see him as a target, and extort him for money from his commissary fund. But Williams knows prisoners who are supporters of him too, and they protect him for now, he said.When reached for comment, David Owen, communications director for the Missouri Department of Corrections, did not address specific conditions Williams said he's experienced at Eastern Reception. He emphasized that those incarcerated have "the opportunity to voice his or her complaints about any issues that may arise during incarceration" at any time, including concerns or threats made against them, and "request they be placed in protective custody if they are concerned for their safety or well-being."When Williams gets out of prison, he's hoping to open a youth center in Ferguson, to give kids who grew up poor like him a chance to build community. His plans are still vague, but he feels committed to doing something positive with children.He said he's disappointed that little has changed since Ferguson–—that cops are still killing African Americans around the country with little in the way of punishment. But he's hopeful others will take up the mantle and fight like he did."People need to keep representing, and not to back down or stop just because the cops say so," he said, "because they don't stop when we say so."Follow Peter Moskowitz on Twitter.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Watch Thomas Morton head to Ferguson, Missouri at the height of the historic protests there:

Williams is about two years into his eight-year sentence. He said he occupies his time by reading the Bible, talking on the phone with his mom and other activists, and trying to learn more about his case."It's pretty nerve-wracking in here," he said. "A lot of people recognize me. Some corrections officers are racist. Some call me 'QuikTrip.' Some ask if I have a lighter."

Advertisement

Advertisement