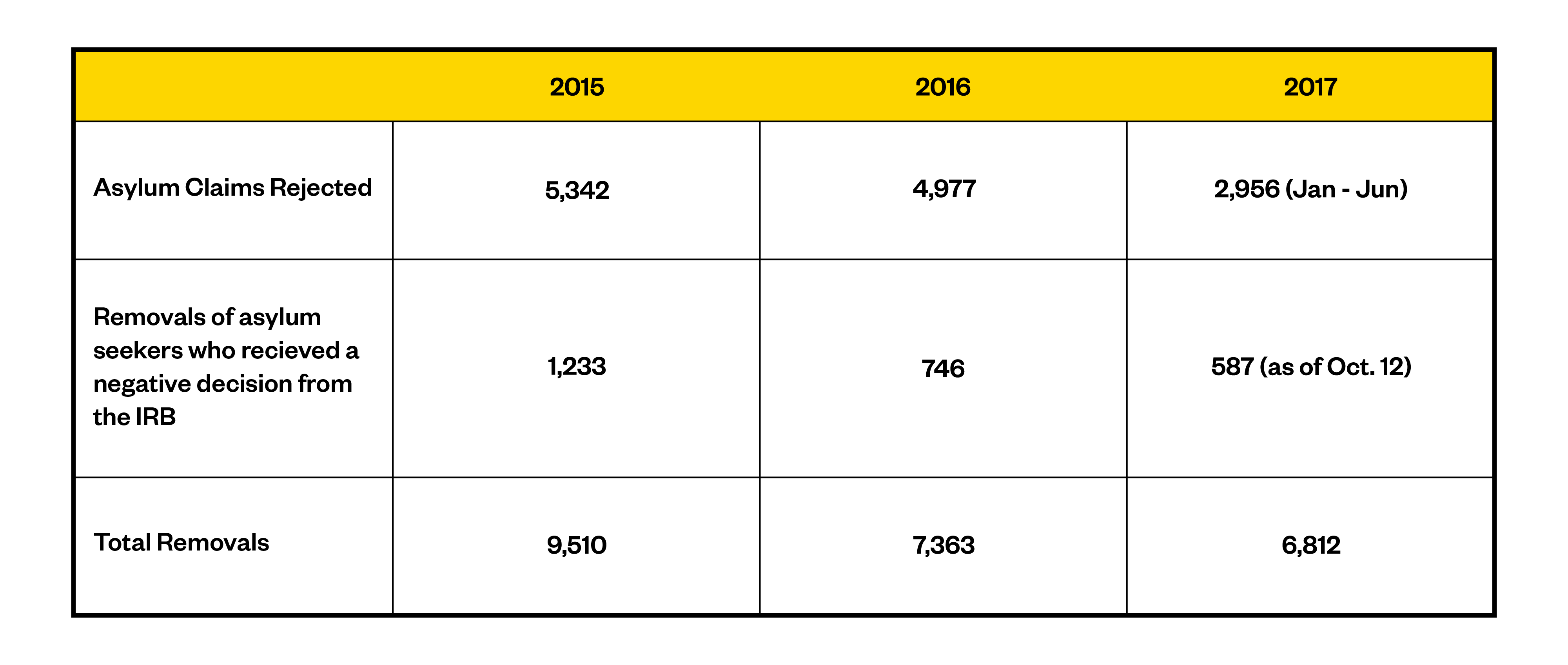

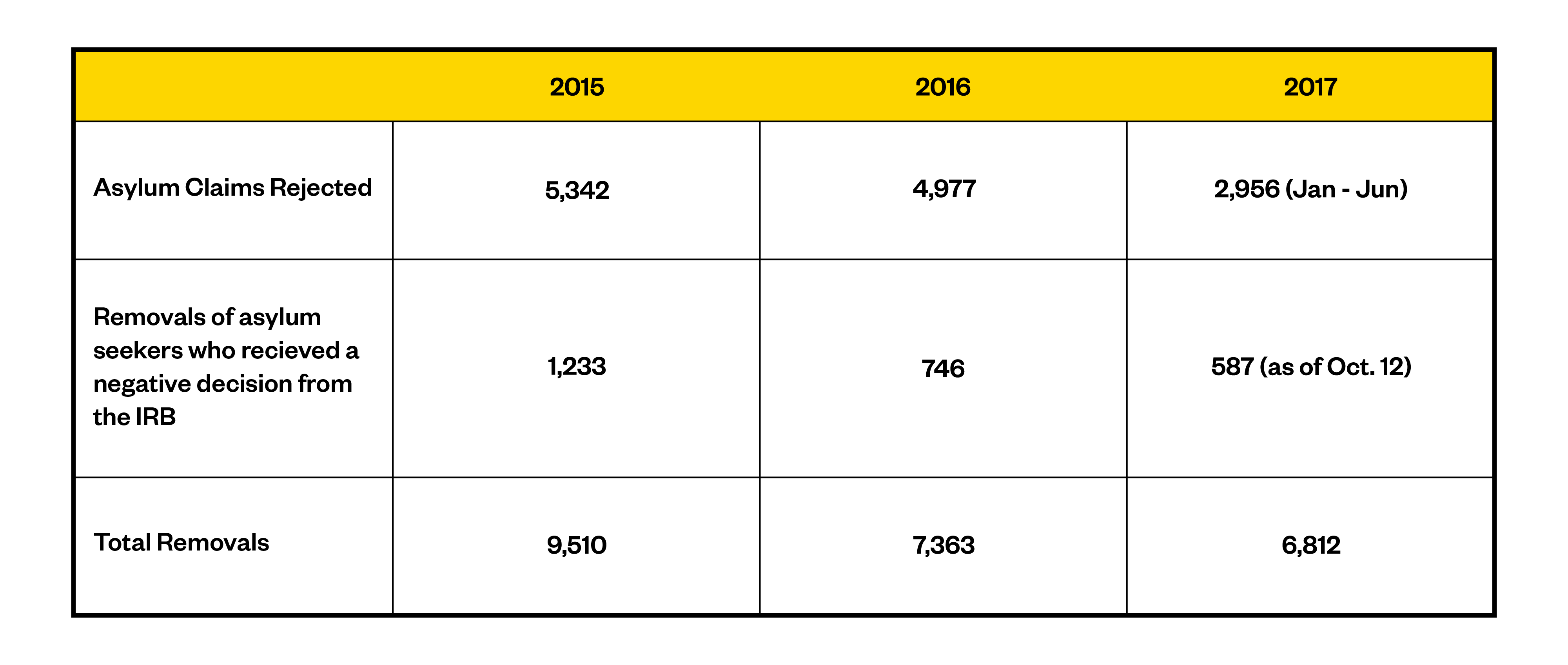

Canadian authorities have been slow to deport failed asylum seekers this year, according to new government data obtained by VICE News. As border officials continue to miss their own targets for removing people whose claims have been denied, some migrants languish indefinitely in immigration detention.However, immigration experts say the backlog may actually be a good thing for those who are striving to start a new life, despite being denied refugee status in Canada.While over 32,000 asylum seekers have arrived in Canada so far this year, including 15,000 who were arrested by RCMP officers after walking across the border illegally, just 587 failed asylum seekers have been deported, according to Canadian Border Service Agency (CBSA) figures obtained by VICE News. With a total of 2,956 rejected asylum claims recorded until June of this year, the agency is set to miss its target of removing 80 percent of failed refugee claimants.The department’s performance report for 2015-2016 showed that 53 percent of failed asylum seekers were still in Canada a year later, meaning the agency also missed its target by a wide margin last year.Conservative politicians have been demanding answers from the CBSA on the issue, with some questioning whether the government knows the whereabouts of failed claimants who aren’t supposed to be in the country.“How many of these failed asylum seekers have slipped through the cracks and whose current whereabouts the government has no idea of?” asked Conservative MP Larry McGuire during a House of Commons immigration committee meeting in October.In most cases, failed refugee claimants and their lawyers are not complaining.“They’re perfectly happy that the CBSA is slow in deporting them,” Toronto-based immigration lawyer Jared Will told VICE News. “It’s often quite difficult and expensive to come to Canada, and [refugee claimants] don’t do it on a whim. The fact that the CBSA is slow in deporting them is good news.”The slow pace of deportations, however, means some migrants whose claims were rejected are held in immigration detention if authorities fear they won’t show up for removal or if they have a previous criminal record.A lack of documents proving citizenship and reluctance from countries of origin to accept deportees mean some people can spend weeks or months in immigration detention due to the slow pace of removals, sometimes alongside convicted criminals, despite having never committed a crime.The average immigration detention period is about three weeks, but some people can stay incarcerated for months or years.A federal court judge ruled in July that immigrant detainees can be held indefinitely.“There’s a very small number of people who have exhausted their recourses, and are in detention and pending removal,” said Will. He is representing a failed refugee from Gambia who has spent over four and a half years in a maximum security jail because the Canadian government has been unable to deport him.“They would in some situations prefer to be removed sooner rather than later,” he said.As of April, there were 53 people who had been in immigration detention for over six months, according to Will. The removal figures obtained by VICE News are current as of October, but likely don’t include many claimants from claimants large influx of Haitians and other migrants who left the U.S. this summer to seek asylum in Canada, following a crackdown on immigration from the Trump administration. Few of those claims have actually been processed, immigration authorities said.Of about 32,000 asylum seekers who arrived in Canada so far this year, more than 15,100 entered the country illegally, usually by walking across the Quebec border.Most of these cases haven’t been heard yet. As of September, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) was dealing with a backlog of 40,800 asylum claims and a projected wait time of 17 months.As the IRB deals with a pileup of unheard cases, the system is also jammed on the other end, with the CBSA facing a “removal inventory” of about 15,000 people at any given time.While there have been dramatic spikes in the number of removals to Haiti and Mexico — big sources of asylum seekers in Canada this year — it’s not recent asylum claimants who are being deported.Five hundred and forty people were deported to Haiti as of Oct. 24, up from 100 in all of 2016, a five-fold increase in removals to the poorest country in the western hemisphere. The vast majority of these deportees were not asylum seekers. Only four failed asylum seekers were deported from Canada to Haiti in the first nine months of 2017, according to CBSA data.Deportations to Mexico doubled this year: as of Oct. 24, 865 people were deported to Mexico, up from 436 removals last year. Out of these 865 deportees, only 41 were failed asylum claimants, with the rest removed for other reasons.The CBSA would not speculate on why there had been increases in total removals for certain countries, saying only that “removal numbers fluctuate year to year.”But Janet Dench of the Canadian Council for Refugees has offered some possible explanations. Many Mexican nationals who arrived in Canada after a visa requirement for travelers was lifted at the end of 2016 were grilled by CBSA officials, who had them deported immediately based on suspicion that they were intending to settle in Canada, explained Dench, who has heard such reports anecdotally. Deportations, in these cases, would have happened before migrants had a chance to file refugee claims.It also makes sense that there would be more deportations to Haiti this year since the government halted a temporary suspension of removals to the country in August of 2016 which had been in place since 2010, Dench said.While deportations of failed refugee claimants have been slow, Canada has carried out hundreds of other kinds of removals to countries that have been deemed too dangerous for civilians, including 136 to Afghanistan in the past three years, 268 to Iraq, and 183 to the Democratic Republic of Congo.All three countries are currently covered by the government’s temporary suspension of removals program, which prevents deportations to places where the entire civilian population is at risk. Anyone who isn’t allowed into Canada on the grounds of criminality, international or human rights violations, organized crime or security, however, can still be deported.

The removal figures obtained by VICE News are current as of October, but likely don’t include many claimants from claimants large influx of Haitians and other migrants who left the U.S. this summer to seek asylum in Canada, following a crackdown on immigration from the Trump administration. Few of those claims have actually been processed, immigration authorities said.Of about 32,000 asylum seekers who arrived in Canada so far this year, more than 15,100 entered the country illegally, usually by walking across the Quebec border.Most of these cases haven’t been heard yet. As of September, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) was dealing with a backlog of 40,800 asylum claims and a projected wait time of 17 months.As the IRB deals with a pileup of unheard cases, the system is also jammed on the other end, with the CBSA facing a “removal inventory” of about 15,000 people at any given time.While there have been dramatic spikes in the number of removals to Haiti and Mexico — big sources of asylum seekers in Canada this year — it’s not recent asylum claimants who are being deported.Five hundred and forty people were deported to Haiti as of Oct. 24, up from 100 in all of 2016, a five-fold increase in removals to the poorest country in the western hemisphere. The vast majority of these deportees were not asylum seekers. Only four failed asylum seekers were deported from Canada to Haiti in the first nine months of 2017, according to CBSA data.Deportations to Mexico doubled this year: as of Oct. 24, 865 people were deported to Mexico, up from 436 removals last year. Out of these 865 deportees, only 41 were failed asylum claimants, with the rest removed for other reasons.The CBSA would not speculate on why there had been increases in total removals for certain countries, saying only that “removal numbers fluctuate year to year.”But Janet Dench of the Canadian Council for Refugees has offered some possible explanations. Many Mexican nationals who arrived in Canada after a visa requirement for travelers was lifted at the end of 2016 were grilled by CBSA officials, who had them deported immediately based on suspicion that they were intending to settle in Canada, explained Dench, who has heard such reports anecdotally. Deportations, in these cases, would have happened before migrants had a chance to file refugee claims.It also makes sense that there would be more deportations to Haiti this year since the government halted a temporary suspension of removals to the country in August of 2016 which had been in place since 2010, Dench said.While deportations of failed refugee claimants have been slow, Canada has carried out hundreds of other kinds of removals to countries that have been deemed too dangerous for civilians, including 136 to Afghanistan in the past three years, 268 to Iraq, and 183 to the Democratic Republic of Congo.All three countries are currently covered by the government’s temporary suspension of removals program, which prevents deportations to places where the entire civilian population is at risk. Anyone who isn’t allowed into Canada on the grounds of criminality, international or human rights violations, organized crime or security, however, can still be deported.

Advertisement

‘GOOD NEWS’

Advertisement

‘REMOVAL INVENTORY’

Advertisement