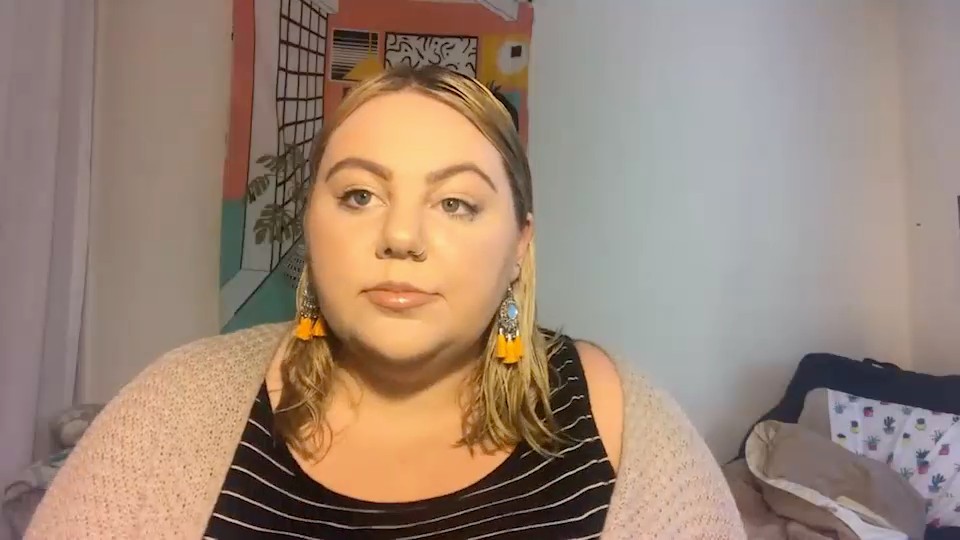

Left Image: Christine Blasey Ford. Photo by Melina Mara-Pool/Getty Images. Right Image: Donald Trump at the rally he used to mock her. Photo by MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

Kaethe Morris Hoffer worried she might be shouting. For many women, especially those who work with survivors of sexual assault, it’s getting harder by the day not to scream.“The discussion about false rape allegations is frankly a profound waste of time,” the executive director of the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation told me when I asked about the pervasive myth, parroted by President Trump Tuesday night, that women routinely fabricate stories of sexual assault. "The reason it keeps cropping up is not because it has any basis in truth, but because it is effective. It promotes unreasonable doubt that lands on virtually every survivor."Casting doubt seems to have been Trump’s aim when he trotted the lie out Tuesday, first to the press corps on the White House lawn, and later at a rally in Mississippi. It was ugly, even for him—a man who has himself been accused of sexual violence or harassment by many women.

“They want to destroy people,” the president said, apparently referring to survivors like Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh attempted to rape her at a party in the 80s. He took time from what was ostensibly a rally on behalf of a Republican candidate to mock the woman's harrowing account at length, to the delight of his fans and the horror of basically everyone else on Earth. “These are really evil people," he said, hours after arguing it was a "very scary time" to be male in the United States of America.In fact, it's the lives of survivors who report their assaults that are far more likely to end up “in tatters," as Trump put it, than the lives of the people they accuse. This can get lost amid the broadsides being delivered by the president and his Adult Son in sort of a dynastic #MeToo backlash, but it doesn't change the underlying facts.“Many, many people report that the trauma and the pain [of reporting their rape] is equivalent to and sometimes greater than the pain caused by the rape itself,” Morris Hoffer told me.Prosecutors know this. Police do, too. In fact, University of Kansas Law Professor Corey Rayburn Yung told me, many cops warn survivors exactly what seeking justice will cost them—how much time and dignity they will lose, how little hope of an arrest or conviction—as a way of urging them to drop their case. Using federal crime numbers, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) estimated that for every 1,000 rapes, 57 reports will lead to arrests, 11 will be referred to prosecutors, and just seven cases will lead to felony conviction.“It’s a disaster for you if you falsely report, or even truly report a rape,” Yung said. “Even within the false reporting numbers, we have reason to believe those are inflated. It’s a dumping ground for cases police don’t want.”Mountains of evidence suggest that only a small fraction of rapes reported to police ever prove to be “unfounded”, as federal law enforcement dubs false claims; the actual figure is generally pegged at between 2 and 10 percent. Yung said only a single analysis has ever deviated from that range, and it's been largely discredited. And while there is a long and shameful history of men of color being falsely accused of rape in America—especially at the height of Jim Crow—evidence of the same thing happening to powerful white men like Kavanaugh is vanishingly rare.“The false reporting rate is lower than lots of crimes,” Yung added, singling out robbery—the metaphor so many researchers, prosecutors, and victims’ advocates reach for when they try to describe how hard it is to report a rape.“Nobody ever thinks the guy who got robbed made up the robbery,” explained New York City defense attorney and former Manhattan sex crimes prosecutor Matthew Galluzzo. “Nobody asks what he was wearing. Nobody questions him, 'Why were you alone there?'"Yet fake robberies abound, amounting to the bread and butter of insurance fraud.“Most people who are sexually assaulted don’t make any complaint to law enforcement ever,” Galluzzo told me. “When I get people who’ve actually come forward, you want to make sure we get all the way there. I’ve had to literally hold their hand to get through it.”As a prosecutor, he said, he sometimes heard claims he believed but couldn’t prosecute, rarely ones he didn’t credit as true. Patti Powers, a former sex-crimes prosecutor now serving as an attorney advisor at Aequitas, a group that advises law enforcement on cases involving violence against women, said authorities were slowly coming to understand that “perceived impediments” to prosecution can in fact corroborate a truthful account—for example, that "drugs and alcohol can be used in a predatory way."So why won’t the myth die?“It relies upon a fundamental assumption that women are idiots,” Morris Hoffer, the victim’s advocate, argued. “They think of us as so subhuman that we would routinely do something that is almost always a ticket into humiliation, degradation, shame, punishment and excisement from our community.”What’s worse, she said, it suggests we can’t even lie well.“Most people who don’t have a lived experience of sexual assault think of rape as a vicious beatdown plus sexual penetration,” she told me. So why would a story designed to discredit rest on accusations that look so little like rape on TV? “Women would have to be fundamentally without any sense at all to invent accusations [like Blasey Ford's] that don't conform to what people expect a sexual assault looks like."But Yung, the law professor, said many men prefer the lie about false accusations because it expiates them.“Many men do realize they’ve crossed a line at some point, and they’re really scared,” he told me. “But rapists don’t think they’re rapists. This gives them an extra layer of denial.”If you need someone to talk to about an experience with sexual abuse, you can call the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network's hotline at 800.656.HOPE (4673), where trained staff can provide you with support, information, advice, or a referral.Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.Follow Sonja Sharp on Twitter.

Advertisement

“They want to destroy people,” the president said, apparently referring to survivors like Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh attempted to rape her at a party in the 80s. He took time from what was ostensibly a rally on behalf of a Republican candidate to mock the woman's harrowing account at length, to the delight of his fans and the horror of basically everyone else on Earth. “These are really evil people," he said, hours after arguing it was a "very scary time" to be male in the United States of America.In fact, it's the lives of survivors who report their assaults that are far more likely to end up “in tatters," as Trump put it, than the lives of the people they accuse. This can get lost amid the broadsides being delivered by the president and his Adult Son in sort of a dynastic #MeToo backlash, but it doesn't change the underlying facts.“Many, many people report that the trauma and the pain [of reporting their rape] is equivalent to and sometimes greater than the pain caused by the rape itself,” Morris Hoffer told me.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement