This article originally appeared on VICE Germany.Albrecht Becker lived to tell the tale. In 1935, the photographer was imprisoned by the Nazis for being gay, a crime that was punishable by death in Hitler's Germany. Yet more than 60 years later, in 1996, he sat down to film Rosa von Praunheim's short documentary Liebe und Leid (Love and Suffering), smiling, to share what life was like as a gay man under Nazi rule.

Advertisement

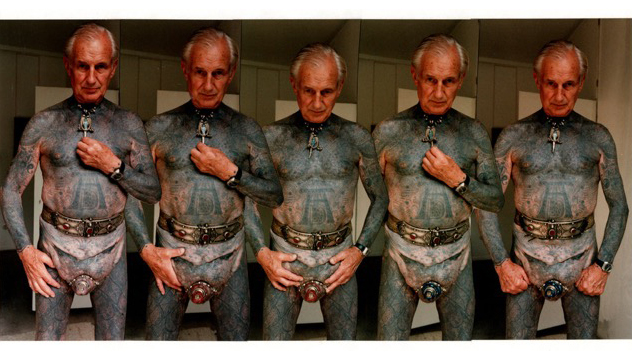

Becker, a rather dapper 90-year-old man at the time, wore a light blue shirt with a loosely fitted bow tie. A dark tattoo peeked out from beneath his collar – a sign of the second half of his story. After landing himself in a bunker on the Eastern Front, he became a radical artist, tattooing himself and discovering the pleasures that can be found in pain.Some of Becker's self-portraits look like photoshopped images from the sub-genre of the internet that tries to imagine what people with full-body tattoos will look like when they're elderly. Becker was proud of his sexuality, his body and his experiments, even those that failed – including one that left his penis permanently disfigured. This is one of the reasons the art world has rediscovered his work. From the 7th to the 10th of March, 2019, Becker's photographs will be shown at the Independent Art Fair in New York.

Becker would often paint over his photographs.

By the time he died, in 2002, Becker had left behind several interviews, his autobiography and eyewitness accounts that tell us a bit about his life and what motivated his work.In Liebe und Leid, Becker explains that being gay wasn't really a problem at the start of Nazi rule in Germany. Paragraph 175 had forbidden sex between men, but nobody really cared in Würzburg, where Becker lived in the 1930s. He and his lover, a professor who was 20 years his senior, slept together without going to great lengths to hide it. He says the Nazis weren't interested in him, and politically, he wasn't interested in them either.

Advertisement

However, all that changed in July of 1934 after the The Night of the Long Knives and the murder of SA commander Ernst Röhm. With the elimination of Röhm, Hitler's power was consolidated. The persecution of those who didn't fit into the National Socialist worldview began. Shortly after Christmas the same year, the Gestapo summoned Becker and his lover. "We went in unknowingly and we didn't return home until three years later," Becker says in the film.

WATCH: Inside LA's Craziest Pansexual Nightlub

"I'm gay and everyone knows it," he told the Gestapo interrogator. Even then, in his late twenties, Becker was sure of himself. But that confidence brought some naivety. "Unfortunately, I gave up the names of friends I had slept with." He didn't think anything of it at the time.Becker got lucky and was sentenced to three years in prison in Nuremberg, probably because he didn't deny his "guilt" and because, in the process, he denounced others. "If a gay person was taken to Dachau concentration camp, that was without a doubt the last you'd see of them," Becker told the USC Shoa Foundation when he was interviewed about the Nazis persecuting gay people.Once released from prison, Becker slipped back into his old way of life. As a decorator, he brought a bit of colour to the windows of Nazi Germany, and then bought himself a Leica to photograph his friends. But in 1940 he was drafted, and posted to Russia, just outside Stalingrad. Becker joked in his autobiography that he was at least looking forward to being surrounded by young men again once he got to the front.

WATCH: Inside LA's Craziest Pansexual Nightlub

"I'm gay and everyone knows it," he told the Gestapo interrogator. Even then, in his late twenties, Becker was sure of himself. But that confidence brought some naivety. "Unfortunately, I gave up the names of friends I had slept with." He didn't think anything of it at the time.Becker got lucky and was sentenced to three years in prison in Nuremberg, probably because he didn't deny his "guilt" and because, in the process, he denounced others. "If a gay person was taken to Dachau concentration camp, that was without a doubt the last you'd see of them," Becker told the USC Shoa Foundation when he was interviewed about the Nazis persecuting gay people.Once released from prison, Becker slipped back into his old way of life. As a decorator, he brought a bit of colour to the windows of Nazi Germany, and then bought himself a Leica to photograph his friends. But in 1940 he was drafted, and posted to Russia, just outside Stalingrad. Becker joked in his autobiography that he was at least looking forward to being surrounded by young men again once he got to the front.

Advertisement

He stayed in Russia until the summer of 1944, but says he never fought at the front. He also didn't find any lovers in the army. Nevertheless, he explored his masochistic side while he was there.

Becker gave himself a Prince Albert piercing using the Boreno tribe for inspiration.

Becker said that during the war he quickly realised he couldn't openly reveal his sexual orientation, in fear of being shot dead or sent to a concentration camp. In other words, he didn't have sex for four years, which turned him into something of a sexual explorer. In a bunker, he tattooed himself for the first time: flames on his dick. He used three sewing needles, some woollen thread, a pencil and black ink.He pulled the curtain across his bunk for privacy and realised how much tattooing excited him. "I lay there and tattooed myself, and afterwards, I came. The other guys were playing cards. I found it all strangely funny," Becker explained. From then on, he became obsessed with tattooing.Becker's life on the frontline came to an end when a piece of shrapnel pierced his arm as his division retreated during an air raid. In the military hospital, he got to know art director Herbert Kirchhoff. For the next ten years, they were a couple, living and working side-by-side.

Becker designed dozens of film sets with Kirchhoff and they were awarded the German Film Award twice. This is the well-known, well-documented side of his life. The other side took place in tattoo shops and the queer art scene in Hamburg. Becker moved there in the 1950s and dove headfirst into the world of sadomasochism.

Advertisement

Becker's body canvas was gradually covered with motifs, which he displayed as art. He photographed them, sometimes in costume, more often naked and sometimes during sex.

At a time where Germany was fragmented, the Berlin wall was going up and the world was recovering from devastating warfare, Becker created a world of his own. He had read about a Borneo tribe that ritually pierced the tip of their penises and wore jewellery in the holes, and it fascinated him. It took him two years to train himself to be able to manage the pain, and an entire hour to finally got up the nerve to push the glowing hot needle through the tip of his penis. He threaded a surgical suture through the hole and widened it to an inch in diameter. As an old man, this was one of Becker's favourite stories.In the mid-60s, Becker persuaded himself that his testicles were too small. "I injected them with paraffin," he says in Liebe Und Leid. He had heard that doctors were using liquid paraffin for cosmetic surgeries, but what he hadn't heard is that paraffin can spread throughout the body. Becker injected four litres over several years, until it finally settled in his penis, forming, as Becker put it, a second belly. He could no longer have normal sex or get a proper erection. It was as if his penis had disappeared into a large paraffin bulge."My penis was 18 centimetres long, but in the end, it was only six centimetres," Becker says in the film. He once asked a doctor to remove the bulge, but by then it was too late – the paraffin had absorbed into the tissue. Rather than trying to hide his penis belly, he took more photos of himself, which became the lasting results of his experiment. Documentary filmmaker Hervé Joseph Lebrun, who worked with Becker for four years, claims that this is when Becker truly became an artist.

Advertisement

Becker didn't hide his deformity or seem to care much about what people thought. He also had a pretty big ego, even at the age of 92, when Lebrun first met him. In 1998, Becker called Lebrun, who lived in Paris at the time. He had seen some of the filmmaker's work and invited him to come to Hamburg."After our first phone call, he sent me many photos of himself in sadomasochistic situations," Lebrun tells me. "That was my first impression of Albrecht. It was great!"So Lebrun travelled to Hamburg to see him."Albrecht lived in a beautiful house with a garden," says Lebrun of their first meeting. The house was full of books about tattoos. Then Becker opened a large cabinet to share his impressive dildo collection with him. They talked about photography, sex and the war. "I listened to the stories that this warm-hearted person had to share – and I looked up to him," Lebrun says.He and Becker took photos every day. "Every morning when he woke up, he wanted to create something new." They collaborated for the next four years, until Becker's death on the 22nd of April, 2002, when Lebrun was giving a speech at their last joint private viewing in Lyon.Albrecht Becker had no close relatives and bequeathed a portion of his photographs to Lebrun. The rest he left to the Schwules Museum in Berlin, which is dedicated to showcasing LGBT culture. "I miss him," says Lebrun. "He was a bright light for me, and for all the people around him."