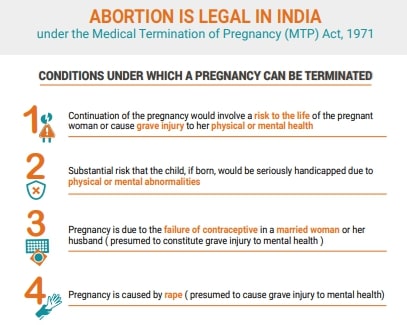

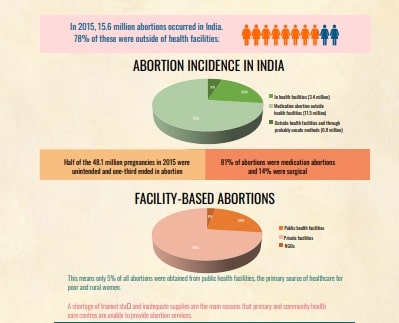

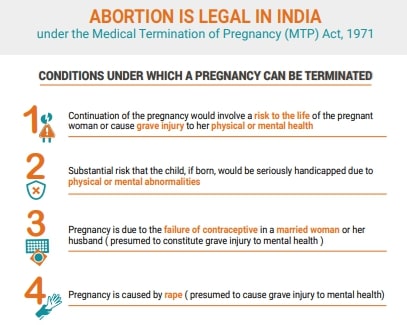

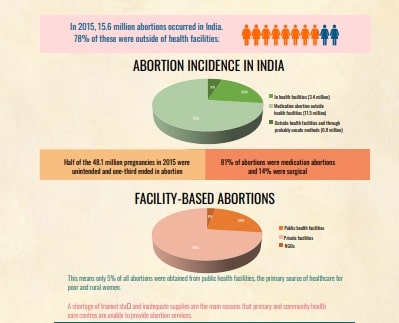

When Shantani*, a resident of West Bengal, was coerced into sex work by her husband, she either had to "accept my fate or keep facing the beatings from my husband that had become a regular part of my life". However, she insists that this was not the toughest part of her ordeal.It was the death of her three children, all of who she didn’t want to give birth to. Of the nine times she conceived because of men who insisted on not having protected sex, six babies survived—two faced intrauterine fetal deaths in the last months of pregnancy, whereas it was only when she was pregnant for the ninth time that Shantani insisted on going for a safe abortion. “It took me that long to gather the courage,” she says. “If I hadn’t gone for an abortion, I am sure I would have died. Also, making sure that I go to a safe clinic was a struggle to convince my husband about.” Shantani now helps other women find a safe clinic for abortion, working as a peer educator in a programme run by the Family Planning Association of India.Millions of Indian women go for unsafe abortions each year. A patriarchal structure, highly inadequate healthcare facilities, illiteracy and social stigma keep this cycle in motion, though a major factor is also an outdated abortion law: the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971. The Act permits abortions after consultation with one doctor up to 12 weeks. Between 12 to 20 weeks, medical opinion of two doctors is required. The right for a woman to decide for herself does not fall under its ambit.“India’s abortion laws cater to the abortion service provider, and not women themselves,” says Anubha Rastogi, an advocate and a legal expert on abortion laws in India. “A woman can’t just go into a clinic and demand an abortion. We need to remember that India’s abortion laws weren’t changed in 1971 as a result of women’s movements, but due to a bunch of doctors concerned over being penalised as criminals for abortion.”The abortion service provider can end an unwanted pregnancy that does not exceed 20 weeks only if it meets certain conditions: a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or of injury to her physical or mental health, a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped, if the pregnancy is caused by rape, or if it’s occurred as a result of failure of a contraceptive used by a married woman. One in three of 48.1 million pregnancies in India ended in an abortion, according to the country’s first large-scale study on abortions and unintended pregnancies that accounted for 2015 data. The country recorded around 15.6 million abortions in 2015, reports the study published in The Lancet, but 73% of those were done outside of health facilities, the unsafe abortions leading to the death of 10 women each day. According to Swetha Sridhar—a researcher on women’s reproductive rights associated with Asia Safe Abortion Partnership—it’s mainly because of India’s overarching patriarchal system. “It governs what we can talk about with parents, what is acceptable behaviour for women and whether she can have premarital sex.”

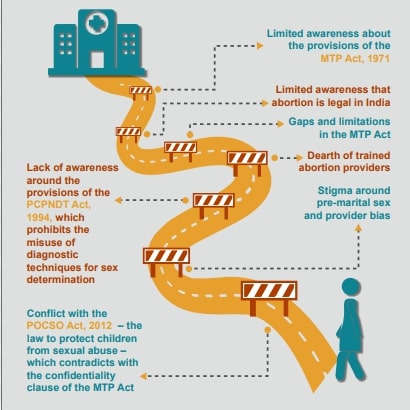

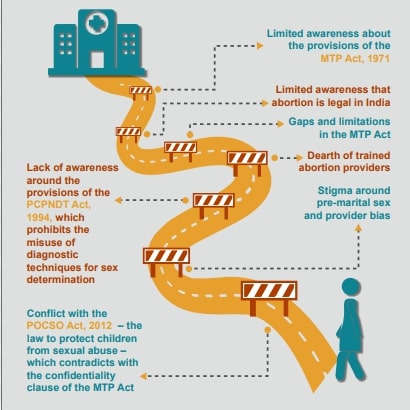

One in three of 48.1 million pregnancies in India ended in an abortion, according to the country’s first large-scale study on abortions and unintended pregnancies that accounted for 2015 data. The country recorded around 15.6 million abortions in 2015, reports the study published in The Lancet, but 73% of those were done outside of health facilities, the unsafe abortions leading to the death of 10 women each day. According to Swetha Sridhar—a researcher on women’s reproductive rights associated with Asia Safe Abortion Partnership—it’s mainly because of India’s overarching patriarchal system. “It governs what we can talk about with parents, what is acceptable behaviour for women and whether she can have premarital sex.” Sridhar says that India’s abortion laws don’t even address unwanted pregnancy in the case of an unmarried women. “The law is silent on them. In such a case, they’d generally get counted either as a married woman facing contraceptive failure or a victim of sexual assault. Often, they need to answer questions from gynaecologists on why they have been sexually active before marriage.”In the case of sexual assault victims, if they have passed the 20-week limit, they often end up giving birth because of the inadequacies of the law. Last year, a 10-year-old rape victim in Chandigarh was denied the right to abort her child when it crossed the 20-week limit, when India’s Supreme Court rejected her family’s plea. She had to go through a delivery done via Caesarean section, and she was told the procedure was to remove a stone.In the case of an abortion involving a minor, the doctor has to mandatorily report it to the police or there is a sentence, as it falls under the POCSO (Protection of Children From Sexual Offences) Act, which says that a minor can’t consent to sexual intercourse.Along with POCSO, the bone of contention for abortion activists in India is also the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994— a law which was introduced to curb sex selective abortions skewing India’s gender ratio. “In the 1991 census, the government came to know that many families were aborting female foetuses in many north Indian states,” says Rastogi. “The knee-jerk reaction has made abortion more difficult.”A lack of awareness amongst doctors and government officials around the PCPNDT Act leads to a clampdown on legal MTP centres and providers, impacting the effective implementation of the MTP Act. Moreover, the government officials often crack down on abortion providers in order prevent female foeticide. In those cases, if any aborted foetus turns out to be a female, a doctor might get entangled in a case without their fault. As per Sridhar, the confusion between the laws also translates into doctors being afraid to perform abortions, lest they might get booked under PCPNDT. “Many doctors have been falsely charged under PCPNDT for even doing late-term abortion, between 12 and 20 weeks of pregnancy.”There is further clashing of the existing laws. Under the MTP act, a pregnant minor can legally receive an abortion with the consent of a legal guardian. But under POCSO, any sexual activity under the age of 18, even if consensual, comes under the scrutiny of law. The casualties in the colliding laws are these girls who then turn to illegal and unsafe abortions.

Sridhar says that India’s abortion laws don’t even address unwanted pregnancy in the case of an unmarried women. “The law is silent on them. In such a case, they’d generally get counted either as a married woman facing contraceptive failure or a victim of sexual assault. Often, they need to answer questions from gynaecologists on why they have been sexually active before marriage.”In the case of sexual assault victims, if they have passed the 20-week limit, they often end up giving birth because of the inadequacies of the law. Last year, a 10-year-old rape victim in Chandigarh was denied the right to abort her child when it crossed the 20-week limit, when India’s Supreme Court rejected her family’s plea. She had to go through a delivery done via Caesarean section, and she was told the procedure was to remove a stone.In the case of an abortion involving a minor, the doctor has to mandatorily report it to the police or there is a sentence, as it falls under the POCSO (Protection of Children From Sexual Offences) Act, which says that a minor can’t consent to sexual intercourse.Along with POCSO, the bone of contention for abortion activists in India is also the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994— a law which was introduced to curb sex selective abortions skewing India’s gender ratio. “In the 1991 census, the government came to know that many families were aborting female foetuses in many north Indian states,” says Rastogi. “The knee-jerk reaction has made abortion more difficult.”A lack of awareness amongst doctors and government officials around the PCPNDT Act leads to a clampdown on legal MTP centres and providers, impacting the effective implementation of the MTP Act. Moreover, the government officials often crack down on abortion providers in order prevent female foeticide. In those cases, if any aborted foetus turns out to be a female, a doctor might get entangled in a case without their fault. As per Sridhar, the confusion between the laws also translates into doctors being afraid to perform abortions, lest they might get booked under PCPNDT. “Many doctors have been falsely charged under PCPNDT for even doing late-term abortion, between 12 and 20 weeks of pregnancy.”There is further clashing of the existing laws. Under the MTP act, a pregnant minor can legally receive an abortion with the consent of a legal guardian. But under POCSO, any sexual activity under the age of 18, even if consensual, comes under the scrutiny of law. The casualties in the colliding laws are these girls who then turn to illegal and unsafe abortions. Another major factor is social stigma associated with abortion in the country. “If a woman has an unwanted pregnancy, they won’t even share it with their family or neighbours. This makes seeking care difficult and further delays early treatment,” says Vinoj Manning, executive director at Ipas Development Foundation, an organisation which provides specialised training to government doctors and teaches them about laws governing abortion. “Due to the stigma, most women would rely on riskier, untrained forms of service providers: quacks, village doctors or most probably, a dai (midwife),” adds Manning.

Another major factor is social stigma associated with abortion in the country. “If a woman has an unwanted pregnancy, they won’t even share it with their family or neighbours. This makes seeking care difficult and further delays early treatment,” says Vinoj Manning, executive director at Ipas Development Foundation, an organisation which provides specialised training to government doctors and teaches them about laws governing abortion. “Due to the stigma, most women would rely on riskier, untrained forms of service providers: quacks, village doctors or most probably, a dai (midwife),” adds Manning. One of the campaigns trying to protect and promote women’s right to make decisions about their reproductive health and bodies—My Body, My Choice—has included local youth as also celebrities. “We want to spread the message that the uterus belongs to women and what should be done with unwanted pregnancy should be solely her choice,” says Shilpa Shroff, assistant coordinator at Asia Safe Abortion Partnership, a partner in the campaign.Though it’s interesting to note that when abortion was made legal in India in 1971, it was hailed as one of the more progressive laws in the world. In late 2014, the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare submitted a list of proposed amendments to the MTP law to the Prime Minister’s Office. The suggested amendments included allowing abortion up to 12 weeks on a woman’s request and till 24 weeks where there is a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or of grave injury to her physical or mental health, to maintain an exception throughout pregnancy for life-threatening cases, as also to drop the word ‘married’ from the law altogether. It didn’t go through.Says Shroff, “It faced much resistance from the government and the lawmakers. Everyone is talking of Beti Bachao. Why shouldn’t it include young girls who die due to unsafe abortions?”* Name changed to protect identity.Follow Zeyad Masroor Khan on Twitter .

One of the campaigns trying to protect and promote women’s right to make decisions about their reproductive health and bodies—My Body, My Choice—has included local youth as also celebrities. “We want to spread the message that the uterus belongs to women and what should be done with unwanted pregnancy should be solely her choice,” says Shilpa Shroff, assistant coordinator at Asia Safe Abortion Partnership, a partner in the campaign.Though it’s interesting to note that when abortion was made legal in India in 1971, it was hailed as one of the more progressive laws in the world. In late 2014, the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare submitted a list of proposed amendments to the MTP law to the Prime Minister’s Office. The suggested amendments included allowing abortion up to 12 weeks on a woman’s request and till 24 weeks where there is a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or of grave injury to her physical or mental health, to maintain an exception throughout pregnancy for life-threatening cases, as also to drop the word ‘married’ from the law altogether. It didn’t go through.Says Shroff, “It faced much resistance from the government and the lawmakers. Everyone is talking of Beti Bachao. Why shouldn’t it include young girls who die due to unsafe abortions?”* Name changed to protect identity.Follow Zeyad Masroor Khan on Twitter .

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement