Photo via Instagram

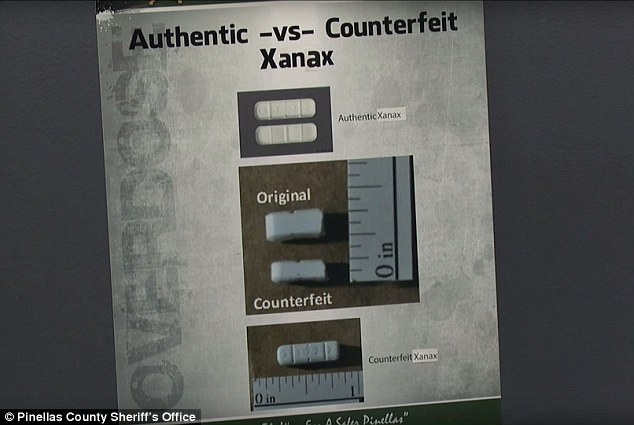

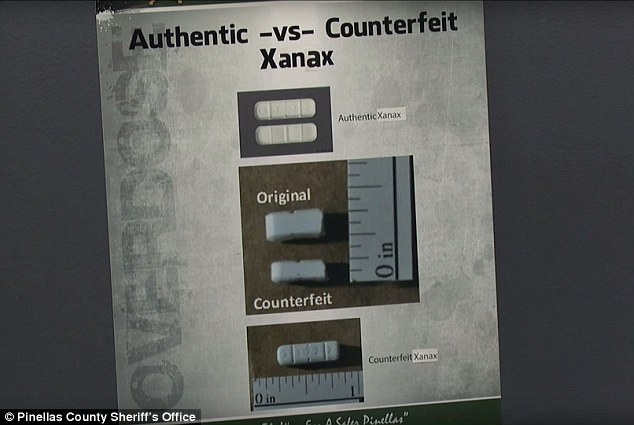

In the heyday of raving in the 90s, you had to have serious connections to get your hands on a pill press machine used to make ecstasy. Today, you can find a mold on Ebay for $72.99 US to make pills that look like Xanax and a pill press machine itself for just a few hundred dollars.What that means is that effectively anyone who knows how to use the internet and has access to it, an accepted form of payment, and an address to receive mail at can get such tools. What people put in it the pills they’re making is up to them and what substances they’re able to source—but we know, at least some of the time, fentanyl is what they choose to use.“We definitely know that it’s happening,” Mitchell Gomez, executive director of the prominent nightlife harm reduction organization DanceSafe, told VICE. “At this point, we’re seeing fentanyl in prescription pills; we’re seeing replica prescription pills of benzos, opioids.”Police and health officials around North America have been warning about fake prescription pills throughout 2017.A search ofpills submitted to EcstasyData.org—a DEA-licensed laboratory that tests drugs submitted to it from the public—turns up a number of substances that have masqueraded as Xanax (a benzodiazepine and anti-anxiety medication) bars in particular in recent years. There are the lesser-known ones that have such long chemical names that I doubt many people reading this will recognize them—3-Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP) and AB-FUBINACA, for example—and then, of course there’s one bar that tested positive for fentanyl. That pill was submitted from Long Beach, California in 2016.Though the proliferation of illicit fentanyl itself is one piece of the overdose crisis the US and Canada are experiencing—which is killing thousands each year—the reality is that fake prescription pills are mixed up in this. While shooting the VICE fentanyl documentary, DOPESICK, our subjects were primarily using fentanyl in the form of fake Oxycontin pills. Though the people who were crushing up and snorting those little blue-green round pills with the “80” printed across it in our film were knowingly doing fentanyl, it was disturbing nonetheless that this is what the drug market had turned to. Fake prescription pills containing a seriously potent opioid were a reality, the amount of the drug in them varied from pill to pill, and people were consuming the pills despite the fact that their friends had died from them.“This is really a function of how drug markets have to operate under prohibition: It’s far easier to smuggle a few grams of fentanyl and just have a pill press in the country that you’re smuggling them into than it is to source and smuggle pharmaceuticals,” Gomez said. “It’s very, very difficult to source 10,000 oxycodones—but purchasing enough fentanyl to press 10,000 [fake] oxycodones is really kind of trivial if you have the right connections.” As well, Gomez said, the profit margin is massive for pressing these kinds of pills.The DEA is currently investigating rapper Lil Peep’s death, which was the result of an accidental drug overdose. His death was reportedly caused by Xanax and fentanyl, which were both found in his system by Pima County Medical Examiner in Arizona. Other substances found in his system following his death included cannabis, cocaine, and Tramadol. Lil Peep, who was 21 years old, died in Tucson while on tour for his first studio album Come Over When You’re Sober. His single “Awful Things” only broke into the Billboard Hot 100 following his death.“We have heard there was some sort of substance he did not expect to be involved in the substance he was taking,” his brother reportedly said following his death. “He thought he could take what he did, but he had been given something and he didn’t realize what it was.”Just hours before Peep’s death on November 15, he posted a picture of himself with what appeared to be pills on his tongue on Instagram. Though the public still doesn’t know for sure what exactly Peep took that night, that hasn’t stopped his fans from speculating that he took fake Xanax. Fake xanax in particular has become a problem in recent years. In Florida, counterfeit xans containing fentanyl reportedly killed nine people in the span of just weeks in 2016.In case you’ve somehow missed all those references to Xanax in music over the years, or how obsessed Tumblr has been with it (check out the #xannies hashtag if you’re drawing a blank), or the number people on social media who’ve posed for selfies with bars on their tongues—the drug has been having a bit of a cultural moment that doesn’t seem to want to end. And if you need any more indication of how much this cultural moment has peaked, there is a rapper literally named “Lil Xan” now, and here’s a video of 17-year-old rapper Lil Pump (of “Gucci Gang” fame) eating a Xanax-shaped cake:Gomez described benzodiazepines, including Xanax, as also being used in party culture, “mostly as a ‘crash pad’ or ‘landing pad’” at the end of the night.Combine this with the misguided sense of trust some in our generation have found in doing pharmaceutical pills over traditional illicit drugs with the current state of the market, and the results aren’t exactly reassuring.“Some of the presses looked really unprofessional just a couple of years ago—you could look at the actual pill and be like, ‘That doesn’t look like a pharmaceutical, that looks like a 1990s ecstasy pill, like someone made it in their garage,” Gomez said. “But now, we’re seeing [counterfeit] pills show up at the lab that, at a casual, visual inspection, look real.”Sault Sainte Marie, a small Canadian community situated on the US border in northern Ontario, has recently seen the onset of what appear to be Xanax bars in the illicit drug market. Terri Nicholson, concurrent disorders counsellor at Sault Area Hospital, sees anyone who presents with a drug overdose at the city's only hospital. Sault Ste. Marie, a city of just under 75,000, is seeing multiple overdoses per day on average. The province it’s located in experienced a 68 percent spike in opioid overdose deaths this year.Nicholson, who described the community of Sault Ste. Marie as currently being in the midst of an overdose crisis, said that in November the hospital saw a number of young people—including high schoolers—present with overdose symptoms after taking what they said was Xanax, but what she said are likely fakes.“The ‘Xanax’ has been around for about three months—a lot of people are doing ‘xannies,’ people under 24 years old is most often what we’re seeing,” Nicholson said.She said the community had multiple overdoses from what was reported as Xanax within the span of a week, including one week where their crisis team saw seven people who had reported taking it.“There hasn’t been a major bust with them, so we don’t know exactly what people are taking [when they say they’ve taken Xanax],” Nicholson said. “We’re pretty sure it’s not genuine prescription pills—there’s a load of fake xannies going around.”“I think the first time people know this is an issue is when they’re hospitalized or someone dies,” Gomez said.

Fake xanax in particular has become a problem in recent years. In Florida, counterfeit xans containing fentanyl reportedly killed nine people in the span of just weeks in 2016.In case you’ve somehow missed all those references to Xanax in music over the years, or how obsessed Tumblr has been with it (check out the #xannies hashtag if you’re drawing a blank), or the number people on social media who’ve posed for selfies with bars on their tongues—the drug has been having a bit of a cultural moment that doesn’t seem to want to end. And if you need any more indication of how much this cultural moment has peaked, there is a rapper literally named “Lil Xan” now, and here’s a video of 17-year-old rapper Lil Pump (of “Gucci Gang” fame) eating a Xanax-shaped cake:Gomez described benzodiazepines, including Xanax, as also being used in party culture, “mostly as a ‘crash pad’ or ‘landing pad’” at the end of the night.Combine this with the misguided sense of trust some in our generation have found in doing pharmaceutical pills over traditional illicit drugs with the current state of the market, and the results aren’t exactly reassuring.“Some of the presses looked really unprofessional just a couple of years ago—you could look at the actual pill and be like, ‘That doesn’t look like a pharmaceutical, that looks like a 1990s ecstasy pill, like someone made it in their garage,” Gomez said. “But now, we’re seeing [counterfeit] pills show up at the lab that, at a casual, visual inspection, look real.”Sault Sainte Marie, a small Canadian community situated on the US border in northern Ontario, has recently seen the onset of what appear to be Xanax bars in the illicit drug market. Terri Nicholson, concurrent disorders counsellor at Sault Area Hospital, sees anyone who presents with a drug overdose at the city's only hospital. Sault Ste. Marie, a city of just under 75,000, is seeing multiple overdoses per day on average. The province it’s located in experienced a 68 percent spike in opioid overdose deaths this year.Nicholson, who described the community of Sault Ste. Marie as currently being in the midst of an overdose crisis, said that in November the hospital saw a number of young people—including high schoolers—present with overdose symptoms after taking what they said was Xanax, but what she said are likely fakes.“The ‘Xanax’ has been around for about three months—a lot of people are doing ‘xannies,’ people under 24 years old is most often what we’re seeing,” Nicholson said.She said the community had multiple overdoses from what was reported as Xanax within the span of a week, including one week where their crisis team saw seven people who had reported taking it.“There hasn’t been a major bust with them, so we don’t know exactly what people are taking [when they say they’ve taken Xanax],” Nicholson said. “We’re pretty sure it’s not genuine prescription pills—there’s a load of fake xannies going around.”“I think the first time people know this is an issue is when they’re hospitalized or someone dies,” Gomez said. As far as harm reduction measures that people who are purchasing prescription pills on the black market can take, Gomez suggested testing every pill that you intend to take with reagent testing and fentanyl test strips (even then, educate yourself on why these methods are not failsafe and have limitations).“At this point, you need to test all of the substances you’re using. We recognize that’s not normal drug consumption behaviour… But it’s the new reality of the market,” he said. Other important measures include not using alone and getting trained in and carrying the opioid overdose antidote naloxone.“Even if you think you’ve taken a Xanax to go to bed at the end of the night, that’s not necessarily what you’re taking,” Gomez said. “You have to treat every pharmaceutical, every baggie of cocaine as if it might be a lethal opiate.”

As far as harm reduction measures that people who are purchasing prescription pills on the black market can take, Gomez suggested testing every pill that you intend to take with reagent testing and fentanyl test strips (even then, educate yourself on why these methods are not failsafe and have limitations).“At this point, you need to test all of the substances you’re using. We recognize that’s not normal drug consumption behaviour… But it’s the new reality of the market,” he said. Other important measures include not using alone and getting trained in and carrying the opioid overdose antidote naloxone.“Even if you think you’ve taken a Xanax to go to bed at the end of the night, that’s not necessarily what you’re taking,” Gomez said. “You have to treat every pharmaceutical, every baggie of cocaine as if it might be a lethal opiate.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement