America is on the brink of socialist revolution. Sorta. A Gallup poll in August suggested that only 45 percent of Americans aged 18 to 29 see capitalism positively, compared to 51 percent for socialism. Though left-wing candidates haven’t performed especially well overall in Democratic primaries this year, the surprise victory of New York’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over a powerful incumbent has been studied and obsessed over by every media source from The Daily Show to Breitbart.

Advertisement

Since then, other candidates associated with socialism have won elections, including Rashida Tlaib, who after a primary victory in Michigan is likely to be one of the first Muslim women in Congress. And 27-year-old Julia Salazar, who won her primary in mid-September, will be the first avowed socialist to serve in New York’s state senate in almost a century.All this had led outlets like Vox to conclude that “the rising socialist left is a major national story.” As the libertarian Reason recently noted, “People are rightly looking for alternatives, and ‘socialism’ is one of them.”But though “socialism” is gaining in popularity, nobody can seem to agree on what it means. Some liberal commentators have suggested that socialists aren’t actually all that distinct from liberals—“The new socialist movement doesn’t look that different from a standard progressive Democratic agenda,” Noah Smith wrote on Bloomberg—while the right has described the movement in apocalyptic terms, with Housing Secretary Ben Carson recently decrying a conspiracy based around the “Fabian Society.”As far as actual socialists are concerned, none of this does a good job of explaining what their movement is about. In the hopes of better understanding that movement, I reached out to nine thinkers with a diverse range of perspectives on socialism and had long, frank, and open-ended conversations with them about what socialism actually is, how it’s influencing US politics, and where the recent surge of enthusiasm for it could ultimately lead us.

Advertisement

Right away it became obvious this new generation of socialists is distinct from the progressives who have traditionally made up the leftmost flank of the Democratic Party. They are less compromising, their rhetoric is more stark, and their demands are often more sweeping. Though there is an open debate within the movement about what “socialism” is, or who the label should properly apply to, the intellectuals, activists, and politicians I’ve spoken to in the past several weeks seemed to broadly agree on several things.They told me that critiquing our capitalist system and refusing corporate donations is a viable election strategy, fighting to reduce economic inequality can dramatically improve the lives of women and communities of color, and our society is much less democratic and free than many people are willing to acknowledge.They also reminded me that American socialism has been on the rise before. In the early 20th century, voters elected two open Socialists to Congress, along with over 100 Socialist mayors and dozens of state legislators. The Socialist politician Eugene Debs received nearly a million votes in the 1912 presidential election. “Let’s say we were a peak athlete in full sprint competing for Olympic gold in that past generation,” Bhaskar Sunkara, the founding editor and publisher of Jacobin, told me. “Up until recently we’ve been in a deep coma and now we’ve just woken up and our pulse is still weak.”

Advertisement

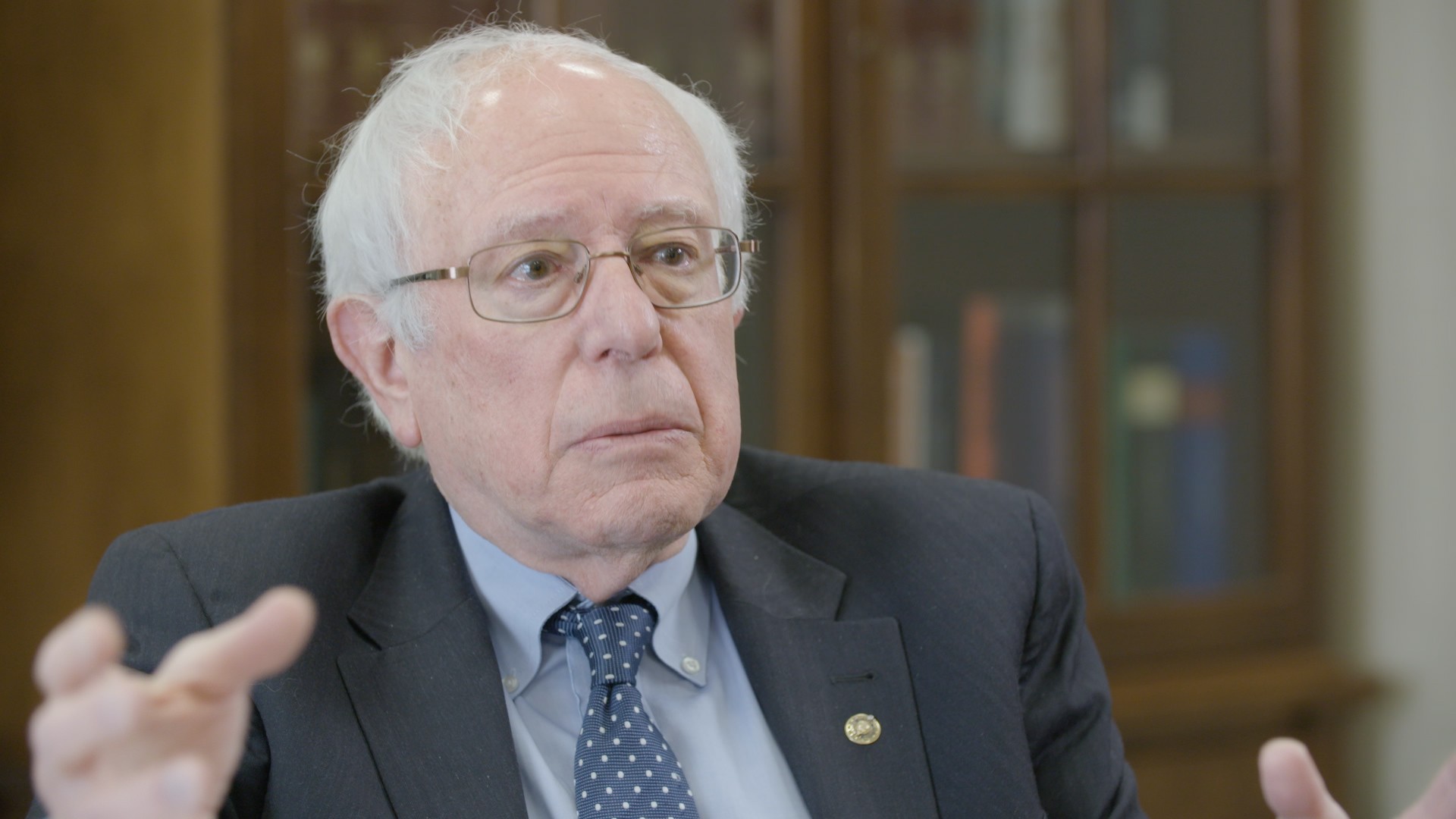

Bernie Sanders at a 2015 rally for better wages in Connecticut. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Still Feeling the Bern

Advertisement

A New Style of Campaigning

Advertisement

This isn’t just about moral high ground. Being independent of entrenched interests can also be a tactical decision. When Carter ran as a democratic socialist in Virginia, his Republican opponent was Jackson Miller, the House majority whip. “This was essentially a guy who was going to have unlimited money,” Carter said. “I was never going to beat him dollar for dollar.” He decided to run without corporate donations and focus on turning out voters jaded by the political system. “We sidestepped that whole fundraising arms race entirely and it paid off,” he explained. Carter won by 1,850 votes.

A banner from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's campaign. Photo by Scott Heins/Getty

Longer Time Horizons

Advertisement

Take Medicare for all. On the surface this doesn’t sound all that revolutionary, especially to a Canadian like myself. “Single-payer healthcare seems like kind of a mundane reform when you’re saying like, ‘Let’s have socialism,’” Nicole Aschoff, author of The New Prophets of Capital and a managing editor at Jacobin, told me. But in reality, she said, “It’s such a huge gain because it opens up all of this kind of breathing room, particularly for women.”A lower-income single mother without health insurance can be financially devastated by a single visit to the hospital. “It can be disempowering to be so precarious,” Aschoff said. Having guaranteed healthcare makes it less risky for that woman to join a union, go on strike and become, for lack of a better word, more “empowered.”Some people I spoke with pointed to Seattle as a case study for what this idea can look like in practice. One of the first things that Kshama Sawant did after being elected to Seattle City Council as a member of Socialist Alternative was to push the city to implement the first $15 minimum wage in the US. To her the fight was never just about higher wages. “It’s about raising the confidence of working people,” she told me. “That will go far beyond [any] one victory.”Ocasio-Cortez and Tlaib will support similar goals on a national level once they get to Congress (both still have to win in the general elections, but that’s likely given they are running in Democratic strongholds). Tlaib in particular has vowed to fight racism and Islamophobia at the same time that she is backing progressive economic policies like a $15 minimum wage. We have “to roll up our sleeves and dig into the structures that have been set up against us,” she told me.

Advertisement

Ending the Capitalist System

Advertisement

When I asked Tlaib, who was endorsed by the Greater Detroit DSA, what she thinks about the wider socialist worldview, she told me, “I’m a member of a lot of organizations; for me I’ve always pushed back on these labels.”This ambiguity about revolutionary economic change sometimes causes socialist activists to question politicians who claim the socialist label. When Black Socialists of America met with Ocasio-Cortez this summer, Z pointed out to her that “most Leftists we talk to and are active with—particularly Black American ones—don’t like or trust politicians (ourselves included).” Z went on: “While your platform and policy proposals are absolutely exceptional, we’re not confident that you have a full, cohesive understanding of what Socialism is or entails, how we are to achieve it, or the base elements of what it would look like in real life.”Sunkara told me he doesn’t think politicians like Ocasio-Cortez are a “one-to-one representation of where most democratic socialist activists and organizations are at.” But he still thinks it’s useful for the socialist cause to have politicians like her in power. “It’s a sign that we’re creating an environment where what’s mainstream is being pushed further to the left,” he said.

DSA members march in Berkeley, California in 2018. Photo by AMY OSBORNE/AFP/Getty

But What About Venezuela?

Advertisement

There are also countries where socialism—at least some form of it—has been successful. “Since the turn of the century, every big country in South America except Colombia has elected a socialist president at some point,” Francisco Toro observed recently in the Washington Post. Peruvian President Ollanta Humala oversaw a 7 percent reduction in poverty, while in Bolivia, it fell by one-third under Evo Morales. “I never would have voted for any of these people,” Toro wrote. “But when you try to evaluate their records, the word that comes to mind is ‘mixed’: successes in some areas, failures in others, and nary a society-wide cataclysm in sight.”If the on-the-ground experience of socialism can vary so much in South America, what would a socialist shift look like in the US?There are many competing answers. Yet Sunkara told me something known as the Meidnar Plan may offer guidance. Decades ago, Sweden considered a policy that would have transferred a fixed share of profits at corporations into funds owned by people who work at them. As these funds grew, it was expected that these workers would eventually gain majority control over Sweden’s stock market.Though the plan was opposed—and defeated—by business owners, Sunkara thinks the US shift to socialism “will look something like that.” He imagines “lots of strikes, lots of protests, lots of pitched battles. It won’t be a friendly conversation.” But he doesn’t see a bloody revolt.

Advertisement

A poster from the 1904 Socialist campaign for president. Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty