Image: Shutterstock

This story is part of When the Drugs Hit, a Motherboard journey into the science, politics, and culture of today's psychedelic renaissance. Follow along here.

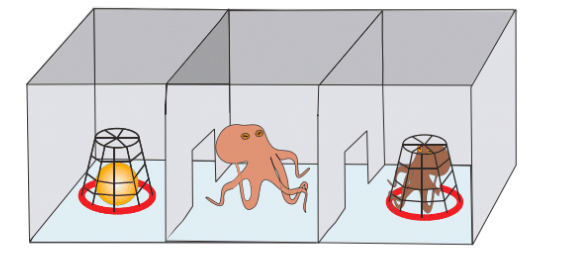

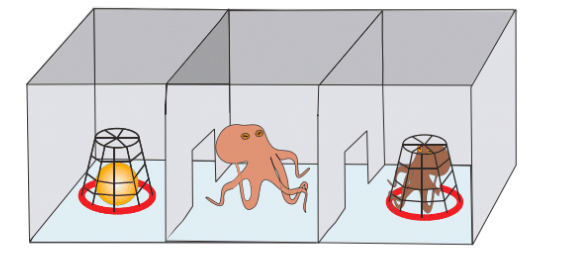

Next time you’re throwing a party, don’t forget to invite some octopuses.According to new research published today in Current Biology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University dosed a species of octopus with MDMA and the octopuses seemed to enjoy it. The experiment was undertaken to study how serotonin is used to promote social behavior.The prosocial effects of MDMA, which is closely related to the recreational drug ecstasy, is well documented in human subjects. It often leads to feelings of emotional connection and is currently the subject of late-stage FDA trials for treating PTSD, anxiety, and other mental disorders. When a human takes MDMA, it binds to a serotonin transporter in the brain to do its magic. As it turns out, the gene for encoding this serotonin transporter is also found in certain species of octopuses, despite their evolutionary lineage being separated from our own by over 500 million years.Although octopuses are generally considered to be solitary, asocial animals, the presence of this gene for encoding MDMA’s principle binding site suggested that octopuses might be susceptible to the prosocial effects of MDMA as well.To test this theory, the Johns Hopkins researchers used the species Octopus bimaculoides, which is the only octopus species that has had its entire genome sequenced. The researchers first tested for baseline social behaviors by placing the octopuses in an aquarium with three separate chambers. The center chamber served as a test area, one of the chambers held another octopus restrained by a mesh, and a third chamber held an object for the octopus to examine. After observing the behavior of sober octopuses, the researchers dosed them with MDMA by placing them in a bath containing MDMA for 10 minutes before returning them to the tank.

After observing the behavior of sober octopuses, the researchers dosed them with MDMA by placing them in a bath containing MDMA for 10 minutes before returning them to the tank.

Next time you’re throwing a party, don’t forget to invite some octopuses.According to new research published today in Current Biology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University dosed a species of octopus with MDMA and the octopuses seemed to enjoy it. The experiment was undertaken to study how serotonin is used to promote social behavior.

Advertisement

Compared to the baseline trials, the octopuses spent far more time interacting with one another in the social chamber of the tank when they were on MDMA. Moreover, the octopuses on MDMA spent far more time touching one another with their tentacles compared to the sober octopuses. According to the researchers, this suggests that the serotonin transporter that binds to MDMA works similarly in octopuses and humans insofar as it promotes sociality.“Despite anatomical differences between octopus and the human brain, we’ve shown that there are molecular similarities in the serotonin transporter gene,” Gul Dolen, a researcher at Johns Hopkins, said in a statement. “These molecular similarities are sufficient to enable MDMA to induce prosocial behaviors in octopuses.”Read More: What We’ve Learned from Giving Dolphins LSD