Protesters at a Trump event in 2016. Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

If you are feeling a little too good about the world, the journalist Edward Luce's The Retreat of Western Liberalism will jolt you back to pessimism in a hurry. In just 200 pages, he surveys economics, history, electoral politics, and international relations to paint a vision of the planet that's as worrying as it is realistic.To hear him tell it, globalization and mechanization has lifted up millions of people in the developing world out of poverty, but it's also harmed the fortunes of the Western middle class, or what used to be the middle class. Even as major cities prospered, towns and rural areas suffered from declining wages and lost jobs. Social cohesion began breaking down, drug addiction rates rose, and anger at the elites who were seemingly letting this happen grew and hardened. Center-left parties largely abandoned populist economic policies in favor of identity politics, which only helped sour the working classes toward them. That's how, according to Luce, America got Donald Trump, the UK got Brexit, and so many far-right figures have come to prominence in Europe.Among the many dangers posed by these leaders is that they'll damage traditional alliances like NATO and the European Union—on Thursday, Trump worried the America's European allies by not making a firm enough commitment to a mutual defense pact. That strain on the Western liberal democratic order comes just as geopolitics is getting complicated thanks to a rising China, a restive Russia, and an ongoing refugee crisis. Add all that up and the status quo that nearly everyone in the West takes for granted suddenly looks very, very shaky."Western liberal democracy is not yet dead, but it is far closer to collapse than we may wish to believe," Luce writes. "It is facing its gravest challenge since the Second World War. This time, however, we have conjured up the enemy from within."Well, shit.I gave Luce a call in advance of his book, which comes out in the US next month, and asked him if things really were that bad, and what elites like him or me could do about it.VICE: How much of the current crisis was inevitable thanks to economic forces that have hurt the Western middle classes, making more people willing to embrace extreme politics?

Edward Luce: I think that a lot of it has been. We think of this as a crisis where in 2016 suddenly a volcano has erupted. But actually it's been spewing and spattering out bits of lava for quite a long time. Look at what's been happening [in the US] since Newt Gingrich became Speaker of the House in 1994, or the rise of the National Front in France—it went from roughly a million votes in the presidential elections in the 90s to 5 million in 2002 to almost 11 million this year. You look at those trend lines and 2016 is not a thunderbolt from the sky. It's actually quite predictable, even if the various forms it takes, like Trump being president, are completely unpredictable.A majority or large minority in society feels that they are not benefiting from government programs, that they keep getting promises that are never delivered, that politics is broken—that's been a feeling that's been building up. It's entirely consistent with, and I think caused by, globalization and the impact of technology on work. This shouldn't surprise us.

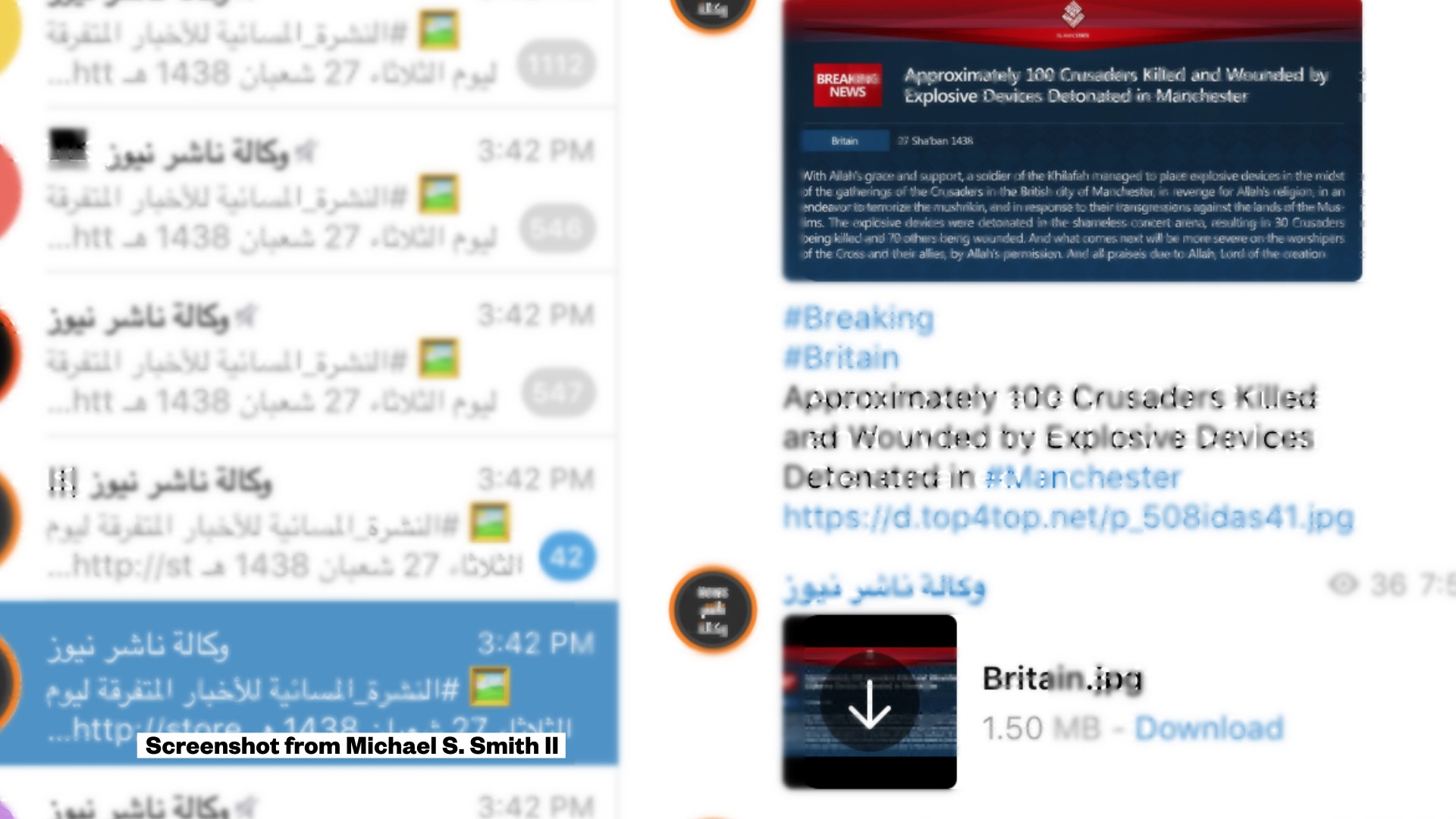

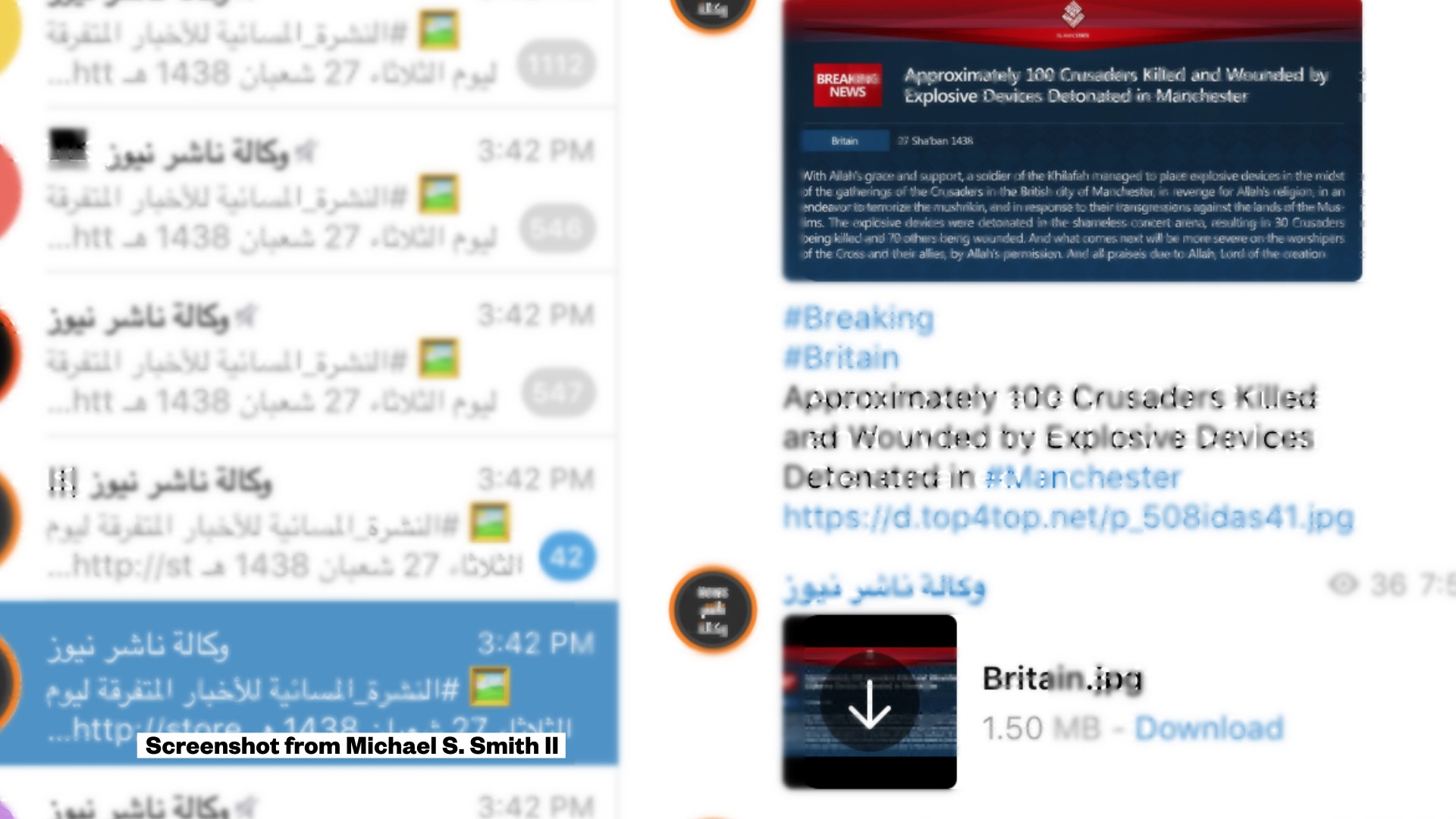

Watch: How the Islamic State claims an attack

Do you think there were moments when the elites could have avoided this situation?

Yes. What ideally we should be seeing in America and Britain and other Western democracies is a massive focus on investing in education and skills, as well as updating the New Deal to fit the gig economy. That would be the right policy response of any liberal democracy that was operating in a vaguely sane, rational way. But what we have in American and Britain is a politics that is taking us further away from that.You've had a very successful career as a journalist and this book has been blurbed by people like former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers; I'm talking to you from a newsroom in New York City. Given the harsh words you had for elites and elites in cities particularly, what can people like us do about any of this?

What we're all doing individually is making this worse. We're quite naturally and understandably getting the best opportunities possible for our children by living in the best areas where the best public schools are, by getting them the best internships, by paying for their tutors on weekends, by structuring their lives, by being two-parent families. We are as elites generally doing the right thing by our children but collectively the impact of that is what's recently been dubbed "opportunity hoarding."

It's a bit of both—let me start with the optics. I was in Philadelphia for the Democratic National Convention last July and it was remarkable the degree to which every minority box was checked [in terms of speakers on stage]. All of them meritoriously, in their own right—don't get me wrong. I believe strongly in gay rights and Black Lives Matter. But it seemed the Clinton campaign was going out of its way to say, "We do not need white working class votes." And I think that's a dangerous game to play—all the other people on stage have a great deal in common with the white working class. They're finding it hard to make ends meet, job security isn't what it was, job retraining isn't easily available. They have a massive, overarching economic interest in common.Center-left parties have drifted away from that, not just the Hillary Clinton campaign and not just the Democrats in America, but New Labour in Britain. Getting back to basic economic security and growth—broad-based growth—is fundamentally, to my mind, not just the right thing to do but a winning strategy as well.Why did parties like the Democrats go away from left-wing economics? Is it just hard to advocate for higher taxes?

Yes that's part of it. It's become a word everyone's allergic to—taxes. But I think there was an element of minority triumphalism, just a simple game of mathematics: Hispanics aren't going to vote Republican again, neither will sexual minorities, women are increasingly turned off, etc. Add these up and we're going to keep winning a little more each time.It enables, I think, for somebody like Trump to come in and say: "Look at these elitists. They've got all the millions they want, and they don't want to share it with you. They just want to use your identity as your primary and only political characteristic and ignore the economic side of who you are and what you have in common." And there is some legitimacy to that critique.

The center-left, in the 1990s, basically embraced the Third Way, which stems from the view that everyone was getting richer, that we had found the elixir of every-rising tides. The left switched from class politics to the politics of personal liberation and aspiration, and it began to downgrade the left-behind. In 2008, [when the economic crisis hit] we realized the middle class was leveraged up to their eyeballs, that they were keeping up by borrowing, not by earning. The left was part of the establishment, and the establishment was looked to as the people to blame, in many cases deservedly.The right was, by some extraordinary feat, able to remake itself as anti-establishment. Not just Trump but the Brexit people were able to present themselves as on the side of the pitchforks. It's preposterous if you think about it, breathtakingly audacious, but effective in the short term. The left wasn't in the position to do that—we saw the left as the establishment. I think that's the principle reason populism is being channeled in right-wing directions, but I think that's evolving.Do you have any good news for people in my generation who will be presiding over the decline of America and the West?

Overall, we have never lived in a more positive time in terms of reduction of poverty worldwide. It's quite extraordinary the degree to which people in Africa, South Asia, East Asia, and Latin America are dropping out of poverty, becoming literate, and acquiring the ability to be individual citizens in potential liberal democracies. It's horribly ironic that we are living in a moment of triumph for the Western model—but outside the West.But what about inside the West?

We do have the room to sort this out ourselves—this is our problem, but it is within our means to address.I'm most encouraged by the millennial generation. There seems to be a more realistic grasp of the situation than older generations might have. There's a larger purpose that people are feeling that they didn't feel a year or two ago, which is very galvanizing, it's not a passive feeling at all. It's a feeling that we have everything to fight for.This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity and length.Buy The Retreat of Western Liberalism here.Follow Harry Cheadle on Twitter.

Advertisement

Edward Luce: I think that a lot of it has been. We think of this as a crisis where in 2016 suddenly a volcano has erupted. But actually it's been spewing and spattering out bits of lava for quite a long time. Look at what's been happening [in the US] since Newt Gingrich became Speaker of the House in 1994, or the rise of the National Front in France—it went from roughly a million votes in the presidential elections in the 90s to 5 million in 2002 to almost 11 million this year. You look at those trend lines and 2016 is not a thunderbolt from the sky. It's actually quite predictable, even if the various forms it takes, like Trump being president, are completely unpredictable.

Advertisement

Watch: How the Islamic State claims an attack

Do you think there were moments when the elites could have avoided this situation?

Yes. What ideally we should be seeing in America and Britain and other Western democracies is a massive focus on investing in education and skills, as well as updating the New Deal to fit the gig economy. That would be the right policy response of any liberal democracy that was operating in a vaguely sane, rational way. But what we have in American and Britain is a politics that is taking us further away from that.You've had a very successful career as a journalist and this book has been blurbed by people like former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers; I'm talking to you from a newsroom in New York City. Given the harsh words you had for elites and elites in cities particularly, what can people like us do about any of this?

What we're all doing individually is making this worse. We're quite naturally and understandably getting the best opportunities possible for our children by living in the best areas where the best public schools are, by getting them the best internships, by paying for their tutors on weekends, by structuring their lives, by being two-parent families. We are as elites generally doing the right thing by our children but collectively the impact of that is what's recently been dubbed "opportunity hoarding."

Advertisement

It used to be that financial capital was expensive and scarce and human capital was plentiful. Now we're living in the opposite world—interest rates are pretty much zero, capital is everywhere, but the return to human skills has gone right up. And parents who are able to have adjusted quite dramatically by investing more and more in their children's skills and development. This is pricing the rest of the children out of realistic prospects of joining the elites.We have to change politically, because no one is going to stop doing the right thing by their children. Elites have to understand that we're retreating, in a way, to a modern-day Versailles, and that road leads to ruin.One of the more contentious parts of your book is a section where you criticized center-left parties like the Democrats for focusing too much on identity politics. Are you talking about optics, or do you think they need to offer new policies too?"Elites have to understand that we're retreating, in a way, to a modern-day Versailles, and that road leads to ruin."

It's a bit of both—let me start with the optics. I was in Philadelphia for the Democratic National Convention last July and it was remarkable the degree to which every minority box was checked [in terms of speakers on stage]. All of them meritoriously, in their own right—don't get me wrong. I believe strongly in gay rights and Black Lives Matter. But it seemed the Clinton campaign was going out of its way to say, "We do not need white working class votes." And I think that's a dangerous game to play—all the other people on stage have a great deal in common with the white working class. They're finding it hard to make ends meet, job security isn't what it was, job retraining isn't easily available. They have a massive, overarching economic interest in common.

Advertisement

Yes that's part of it. It's become a word everyone's allergic to—taxes. But I think there was an element of minority triumphalism, just a simple game of mathematics: Hispanics aren't going to vote Republican again, neither will sexual minorities, women are increasingly turned off, etc. Add these up and we're going to keep winning a little more each time.It enables, I think, for somebody like Trump to come in and say: "Look at these elitists. They've got all the millions they want, and they don't want to share it with you. They just want to use your identity as your primary and only political characteristic and ignore the economic side of who you are and what you have in common." And there is some legitimacy to that critique.

Where are the left-wing populists who could make similar arguments? Why are these movements coming from the right?"It's horribly ironic that we are living in a moment of triumph for the Western model—but outside the West."

The center-left, in the 1990s, basically embraced the Third Way, which stems from the view that everyone was getting richer, that we had found the elixir of every-rising tides. The left switched from class politics to the politics of personal liberation and aspiration, and it began to downgrade the left-behind. In 2008, [when the economic crisis hit] we realized the middle class was leveraged up to their eyeballs, that they were keeping up by borrowing, not by earning. The left was part of the establishment, and the establishment was looked to as the people to blame, in many cases deservedly.

Advertisement

Overall, we have never lived in a more positive time in terms of reduction of poverty worldwide. It's quite extraordinary the degree to which people in Africa, South Asia, East Asia, and Latin America are dropping out of poverty, becoming literate, and acquiring the ability to be individual citizens in potential liberal democracies. It's horribly ironic that we are living in a moment of triumph for the Western model—but outside the West.But what about inside the West?

We do have the room to sort this out ourselves—this is our problem, but it is within our means to address.I'm most encouraged by the millennial generation. There seems to be a more realistic grasp of the situation than older generations might have. There's a larger purpose that people are feeling that they didn't feel a year or two ago, which is very galvanizing, it's not a passive feeling at all. It's a feeling that we have everything to fight for.This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity and length.Buy The Retreat of Western Liberalism here.Follow Harry Cheadle on Twitter.