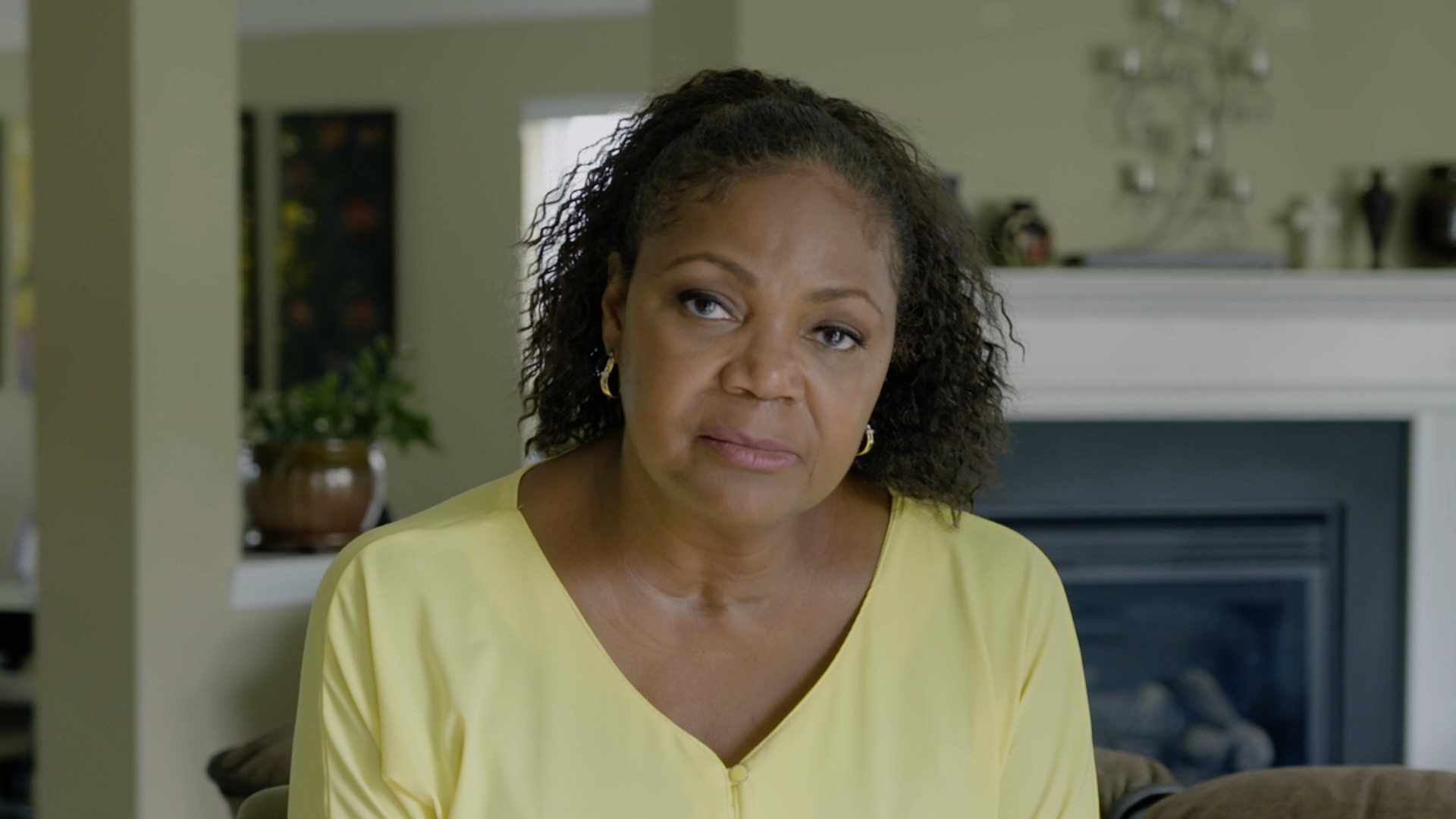

Left Image: Christine Blasey Ford testifying to the Senate. Photo by SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images. Right Image: Republican Senators and Rachel Mitchell in the Senate. Photo by TOM WILLIAMS/AFP/Getty Images

Despite what senators on both sides might say, Christine Blasey Ford is essentially on trial.There has been no FBI investigation, into Ford’s statements nor those of the other women who came forward to, like her, allege sexual violence by Brett Kavanaugh and those close to him. They will not be called to testify, at least not for now. Nor will Mark Judge, Kavanaugh’s Georgetown Prep buddy whose admitted history of unhinged drinking seems to lie somewhere near the core of this story.Yet, eager to swerve a PR blunder by the male-dominated Republican Senate Judiciary Committee majority, the GOP brought in a woman—Arizona sex-crime prosecutor Rachel Mitchell—to do their dirty work for them. They passed just about all of their time to Mitchell so she could conduct what amounted to a mild cross-examination of the Palo Alto University professor at the latest hearings over Kavanaugh's Supreme Court nomination.With the exception of the lawyers she occasionally asked for counsel, Ford was on her own. Yet because she is a psychologist who knows her shit, she was also essentially able to act as her own expert witness—and make anyone doubting her account of what happened look foolish by comparison.

Asked by Democrat Dianne Feinstein, the senator whose office learned of her allegation, how she knew the man who assaulted her was in fact Brett Kavanaugh—how she knew her memory was sound—Ford’s response was scientific.“Just basic memory functions and also just the level of norepinephrine and the epinephrine in the brain that sort of, as you know, encodes—that neurotransmitter that codes memories into the hippocampus and so the trauma-related experience is locked there, whereas other details kind of drift.”“So what you are telling us is, this could not be a case of mistaken identity?” asked Feinstein.“Absolutely not,” Ford replied.Forensic psychologists like Lisa Rocchio are often called to testify in criminal cases to account for just the kinds of myths the president and allies—people defending Kavanaugh—have been spreading about false recollections of sexual violence. “There is such widespread ignorance in the typical reactions of victims [that] it’s necessary to combat that widespread ignorance,” she told me.Prosecutors are often able to introduce these witnesses, "provided that the expert witness is testifying about the state of the science and providing general knowledge that is beyond the typical knowledge base and cannon of a typical juror,” Rocchio explained.But while an expert witness can be extremely helpful to prosecutors—in explaining to a jury why traumatic memories are often so clear even as the events surrounding the trauma fade, and why survivors often don't report the assault right away—defense attorneys can try to prevent it.For example, no such expert was called in the trial I covered that eventually convicted Owen Labrie and helped reveal a culture of ritualistic objectification of young girls at St. Paul’s prep school in New Hampshire. Instead, Chessy Prout, 16 at the time of her three-day testimony, 15 at the time of the assault, was forced to answer to gaps in her memory—while also testifying to feminine grooming.“I was raped,” she burst out, as defense attorney J. W. Carney pressed her in cross examination. “I was violated in so many ways. Of course I was traumatized. I’m sorry.” Labrie was eventually convicted of a felony—using a computer to lure a child—and misdemeanor statutory rape anyway, but was acquitted of felony sexual assault.On Thursday, Ford’s expertise in her own trauma was clear, helping propel her testimony even as the deck was stacked against her: She dropped terms like “sequelae” and explained “fight-or-flight” in great detail.“I was definitely experiencing the surge of adrenaline and cortisol and norepinephrine, and credit that a little bit for my ability to get out of the situation,” she told senators of the moments surrounding her escape from a rape attempt.Jennifer Freyd, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon, was paying close attention to the hearings—and deeply impressed by what she saw. “I would be doing exactly the same thing in her position," she told me. “I would certainly feel like I know something about this and I want to educate people if no one else is doing to do it.”Near the end of her questioning of Ford, Mitchell—the sex-crimes prosecutor—tried to turn the professor's expertise against her.“I've been really impressed today, because you've talked norepinephrine and cortisol and what we call in the profession basically the neurobiological effects of trauma. Have you also educated yourself on the best way to get to the memory and truth in terms of interviewing victims of trauma?”The subtle implication there perhaps being that Ford was too smart—too smooth.“Would you believe me if I told you that there’s no study that says this setting, in increments, is the best way to do that?” Mitchell asked.It came across as a joke, but represented the only avenue of attack Republicans had left.Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.Follow Susan Zalkind on Twitter.

Advertisement

Asked by Democrat Dianne Feinstein, the senator whose office learned of her allegation, how she knew the man who assaulted her was in fact Brett Kavanaugh—how she knew her memory was sound—Ford’s response was scientific.“Just basic memory functions and also just the level of norepinephrine and the epinephrine in the brain that sort of, as you know, encodes—that neurotransmitter that codes memories into the hippocampus and so the trauma-related experience is locked there, whereas other details kind of drift.”“So what you are telling us is, this could not be a case of mistaken identity?” asked Feinstein.“Absolutely not,” Ford replied.Forensic psychologists like Lisa Rocchio are often called to testify in criminal cases to account for just the kinds of myths the president and allies—people defending Kavanaugh—have been spreading about false recollections of sexual violence. “There is such widespread ignorance in the typical reactions of victims [that] it’s necessary to combat that widespread ignorance,” she told me.

Advertisement

Advertisement