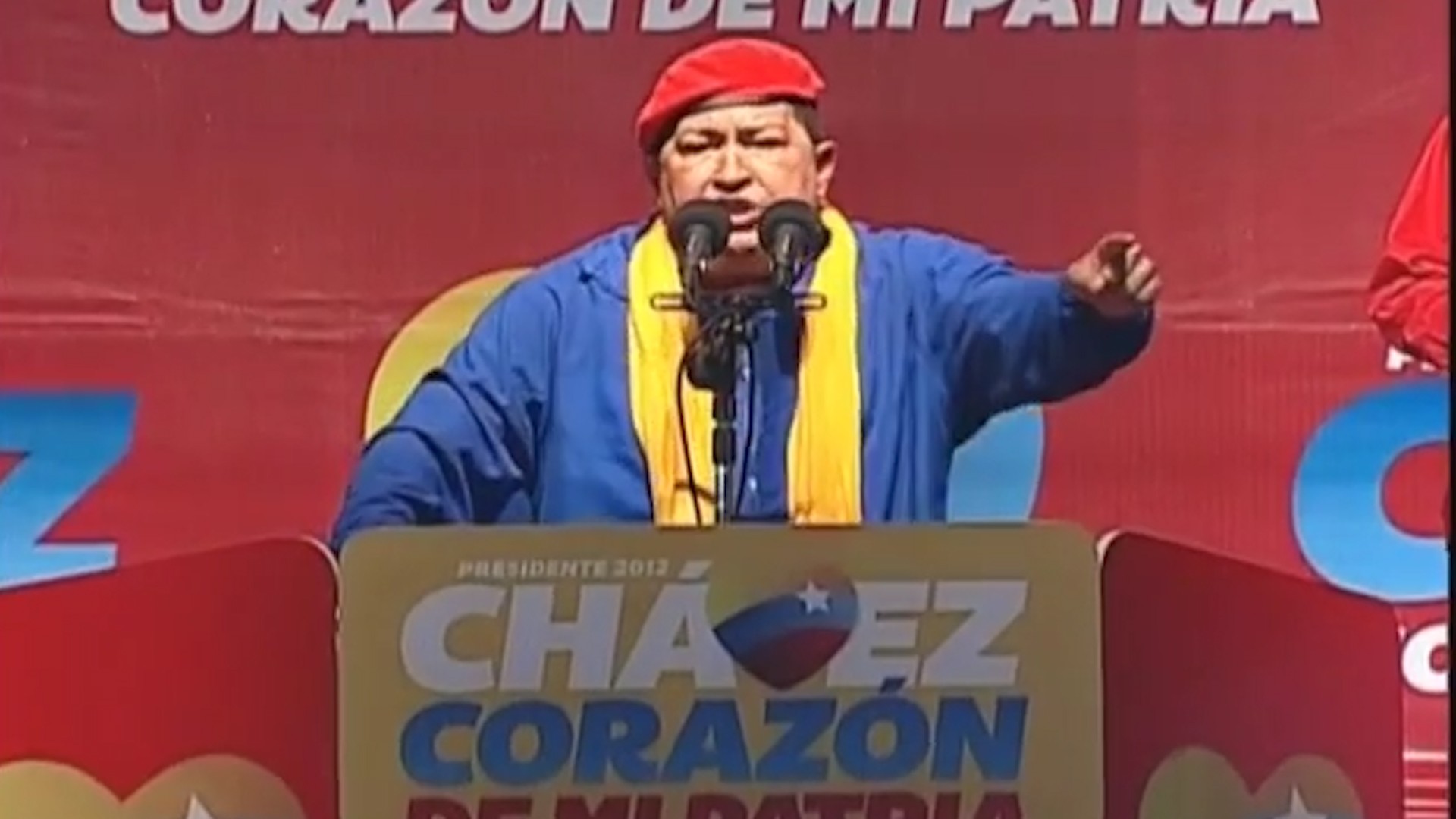

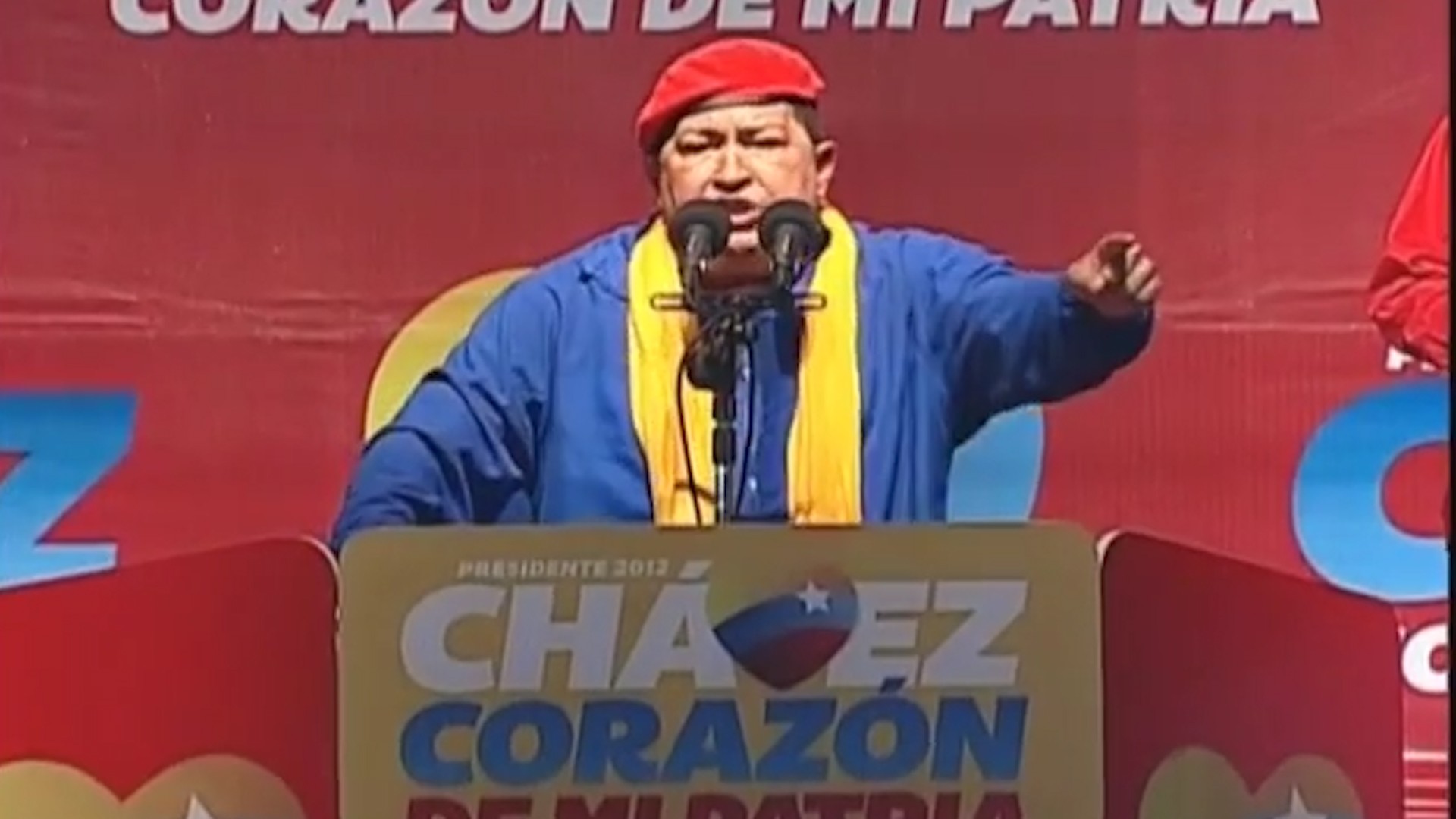

Nigel Farage speaking at the Brexit leave march on London's Parliament Square on the 29th of March 2019. (Steve Thornton / Alamy Stock Photo)

As we head into late May's European Parliament elections, there is a feeling of the Last Days of Rome up in Brussels’ Berlaymont headquarters. The air is sweet with the perfume of regret, and sharp with the bitter tang of what comes next.European elections, with their proportional representation formulas, their low-stakes opportunities to blow-off at the governing elite, and their dismal voter turnout, are a great coming out party for Europe’s populists. Just ask Nigel Farage – back in 2014, UKIP won the EU elections in Britain. They sent 24 MEPs to Brussels out of the UK’s total stack of 76 (most of whom have since evaporated in corruption scandals or fistfights or splits). By comparison, the Conservatives only won 19, and everything that has happened to us since has spilled out of their shock at being beaten into third place.What comes next for the EU began to take shape in Milan last week. There, in a luxury hotel downtown, the Barbarians were planning their assault on the gates. Matteo Salvini, leader of Italy’s populist Lega party, was meeting with representatives of Germany's anti-Muslim Alternative fur Deutschland, the Danish People's Party, the True Finns Party, and the old school Flemish nationalist Vlaamse Belang. Their aim: to build a giant new Eurosceptic bloc within the European Parliament, the biggest of all the blocs.Theirs is a bold project, aiming at nothing less than a reversal in the direction of history since the 1960s – in the words of Hungary’s arch-populist Viktor Orban: “The European Commission is going, we are coming.”They’ve been coming for a long time now – so long it’s occasionally felt like their only purpose was to supply fodder for ponderous leader articles in The Economist. But this spring, they’ll finally have come. Populists of one stripe or another look set to claim one-third of EU Parliament seats, and that will have major implications for the future of Europe.At the heart of a Europe that no longer wishes to have an organised heart, Matteo Salvini has every right to stake his claim as the populists’ new king. A year ago, when Italy was first governed by a coalition of two populist parties, Salvini’s Lega was the junior coalition partner – about half the size of the more left-leaning 5-Star Movement.But that’s turned right round. Voters have liked what they’ve heard from tubby, grinning action-man Salvini, who’s tough on immigration yet smooth on Instagram. 5-Star are now polling nearly half of Lega, which means that in the upcoming elections, Salvini’s "common sense" nationalists are set to take 28 seats, with the more anarchic demagoguery of 5-Star projected to grab another 21. Overall, out of its 74 allocated seats, Italy will be sending the EU 49 populists. Five years ago, the mainstream Social Democrats won 31 seats. Now, they’ve been consigned to electoral oblivion.This week’s meeting is just the start. Next month, Salvini will be meeting with France’s Marine Le Pen, Austria's Freedom Party, Geert Wilders’ Dutch Party for Freedom, Hungary’s Fidesz, and the Polish Law & Justice Party. In all, he hopes to bring the neo-reactionaries of 15 to 20 countries to under his new “European Alliance Of People And Nations”. Now, Europe is heading to a final showdown with the forces of Euroscepticism. Brussels bubble: it’s time to meet the third of the European electorate that hates you.The EU Parliament has a knotty structure. How do you pull together parties from 27 different countries, all with their own brands and local nuances? The answer, it turns out, is that you group the parties – you essentially make coalitions-of-coalitions. So the UK Labour Party sits alongside other Labour Parties in a European Parliament bloc called “The Progressive Alliance Of Socialists And Democrats”; while the Tories sit with the “Europe of Conservatives And Reformers”, the Lib Dems sit with the Liberals, and so on. But because there are about eight of these different blocs, there’s never a clear winner. So you tend to have coalitions between blocs.This system has meant that for the past 25 years, the rulers of Europe have been a “Grand Coalition” of centre-left and centre-right parties – the Gaullists in France, the Social Democrats in Sweden, the Christian Democrats in Germany, all working together to get mainstream things done in a mainstream way. Mainly, that has meant a German-style corporatist-neoliberal economic policy coupled to a progressivist social policy. For evidence on how well the old way is going, look to France, where Marine Le Pen’s hard-right anti-migrant National Rally party are leading the vote share, on 22 percent as per a January poll. Meanwhile, the party that gave France its last President – François Hollande’s Socialists – is polling a dismal six percent.Of course, Rome did not fall in a day. With only a third of MEPs, the populists won’t have enough clout to govern (not that any one group governs), but they will have enough to shut down the changes they don’t like. More tax harmonisation, a co-ordinated external migration policy, a European Army: these ideas die here. For the next five years, the EU will be locked inward, focused more on the battle for its own soul than any grand new schemes if – if – the populists can work together as Salvini wishes.Whether they can is an open question. Populists don’t come in only right-wing flavours, after all.Polling at seven percent in France, just above the Socialists, is Jean-Luc Melenchon’s communistic La France Insoumise. In Greece, hard-left Syriza is still the government, while the post-Occupy internet movement Podemos continues to plug away in Spain (though recently challenged by the right-populism of Vox). These parties would make up a quarter of the populist intake, and even a common yearning for sovereignty is a pretty weak bond when put within the context of the left-populists lining up in the voting lobbies alongside, say, the Austrian Freedom Party, founded by a literal Nazi.They do share a common suspicion of elites, be they Brussels or boardrooms. But they have quite different depths of involvement. Populism might be an international phenomenon, but it also comes in distinctive national flavours. Melenchon’s mob have an old-left view of the EU as a stitch-up by the capitalist classes – a “bosses club”. The Greeks still choke on their memories of betrayal during their 2013 economic crisis, yet they still don’t see a future for themselves beyond the Euro. Podemos want to revoke the Lisbon Treaty, but stay in overall.Look more closely and there are just as many fault lines on the right. Poland’s Law and Justice party, for example, is virulently anti-Russian, while the AfD flirt heavily with Putin and aim to move German foreign policy eastwards… never a good look for Poland.Even if Salvini’s European Alliance Of People And Nations comes to nothing, we know that this is not the climactic battle. The 2019 intake is only Phase One – wait till you see the class of 2024.But we may at least be approaching an early peak – namely, the point at which the fruits of populism start to become the enemy of populism. The smouldering crater of Brexit has left many swashbucklers looking far more timid. Sweden’s Left Party is dropping its 25-year-old call for a Swexit referendum. Both Le Pen and Salvini, too, have cooled on their calls for referendums. At least until Britain stops being on fire for long enough for the true profit and loss of leaving to be calculated, advocating an exit has become, well… unpopular populism.The old hands in Brussels may shudder at the coming tsunami, but they might also try to find opportunity in crisis. Something is coming, yet the true believers have barely noticed their mounting losses, still insisting that the solution to an increasingly unpopular union is more Union.Technocratic centralisation is a pretty 1950s way of organising your internationalism. Perhaps 2019 is a last chance for the EU to be pushed out of its cosy mittel-Europe default mode, to be dragged by the standstill towards discovering more devolved, less bureaucratic ways to run a continent.And if they don’t see it that way yet, Britain may offer to tip the scales. With the Long Extension now locked in, it seems we’ll be sending Farage and his merry gang of minor celebrities back to Brussels, armed with a mandate from the people to break stuff. If six months of that doesn’t make the EU wise up – what will?@gavhaynes

For evidence on how well the old way is going, look to France, where Marine Le Pen’s hard-right anti-migrant National Rally party are leading the vote share, on 22 percent as per a January poll. Meanwhile, the party that gave France its last President – François Hollande’s Socialists – is polling a dismal six percent.Of course, Rome did not fall in a day. With only a third of MEPs, the populists won’t have enough clout to govern (not that any one group governs), but they will have enough to shut down the changes they don’t like. More tax harmonisation, a co-ordinated external migration policy, a European Army: these ideas die here. For the next five years, the EU will be locked inward, focused more on the battle for its own soul than any grand new schemes if – if – the populists can work together as Salvini wishes.Whether they can is an open question. Populists don’t come in only right-wing flavours, after all.Polling at seven percent in France, just above the Socialists, is Jean-Luc Melenchon’s communistic La France Insoumise. In Greece, hard-left Syriza is still the government, while the post-Occupy internet movement Podemos continues to plug away in Spain (though recently challenged by the right-populism of Vox). These parties would make up a quarter of the populist intake, and even a common yearning for sovereignty is a pretty weak bond when put within the context of the left-populists lining up in the voting lobbies alongside, say, the Austrian Freedom Party, founded by a literal Nazi.They do share a common suspicion of elites, be they Brussels or boardrooms. But they have quite different depths of involvement. Populism might be an international phenomenon, but it also comes in distinctive national flavours. Melenchon’s mob have an old-left view of the EU as a stitch-up by the capitalist classes – a “bosses club”. The Greeks still choke on their memories of betrayal during their 2013 economic crisis, yet they still don’t see a future for themselves beyond the Euro. Podemos want to revoke the Lisbon Treaty, but stay in overall.Look more closely and there are just as many fault lines on the right. Poland’s Law and Justice party, for example, is virulently anti-Russian, while the AfD flirt heavily with Putin and aim to move German foreign policy eastwards… never a good look for Poland.Even if Salvini’s European Alliance Of People And Nations comes to nothing, we know that this is not the climactic battle. The 2019 intake is only Phase One – wait till you see the class of 2024.But we may at least be approaching an early peak – namely, the point at which the fruits of populism start to become the enemy of populism. The smouldering crater of Brexit has left many swashbucklers looking far more timid. Sweden’s Left Party is dropping its 25-year-old call for a Swexit referendum. Both Le Pen and Salvini, too, have cooled on their calls for referendums. At least until Britain stops being on fire for long enough for the true profit and loss of leaving to be calculated, advocating an exit has become, well… unpopular populism.The old hands in Brussels may shudder at the coming tsunami, but they might also try to find opportunity in crisis. Something is coming, yet the true believers have barely noticed their mounting losses, still insisting that the solution to an increasingly unpopular union is more Union.Technocratic centralisation is a pretty 1950s way of organising your internationalism. Perhaps 2019 is a last chance for the EU to be pushed out of its cosy mittel-Europe default mode, to be dragged by the standstill towards discovering more devolved, less bureaucratic ways to run a continent.And if they don’t see it that way yet, Britain may offer to tip the scales. With the Long Extension now locked in, it seems we’ll be sending Farage and his merry gang of minor celebrities back to Brussels, armed with a mandate from the people to break stuff. If six months of that doesn’t make the EU wise up – what will?@gavhaynes

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement