Photo by Brandon Magnus/Zuffa LLC

VP of Athlete Health & Performance Jeff Novitzky speaks to MMA trainers and coaches during a UFC Performance SummitIt's been a little over a year since the UFC partnered with United States Anti-Doping Agency and, along with pulling the plug on IVs and pulling the rug out from under fighters who take banned substances, the last 13 months have given rise to a new sub-genre on social media: fighters making surprise-out-of-competition-drug-test posts. There's Demetrious Johnson, ending his Twitch stream after USADA's designees knock on his door. There's Alexander Gustafsson when the agency paid a recent visit, totally not looking like the most irritated person in the room.Well, expect to see a surge in selfies taken with people dressed in business casual that want blood and urine. Jeff Novitzky, the UFC's vice president of athlete health and performance, told MMA Fighting that he expects the USADA program to test UFC fighters roughly 700 times this quarter, up from 450 and 535 tests in the first and second quarters of 2016 respectively. According to the agency's athlete test history database, USADA has performed 161 tests on 141 fighters in Quarter 3 so far. And, Novitzky said, the uptick in testing represents the USADA program in its realized form. "This will be the first quarter—the third quarter of 2016—where we have a fully implemented program."It's a serendipitous time for putting a heavier hand on performance enhancing drug violations, considering the PED-related shitshow that unfolded before and after UFC 200 last month. Jon Jones was pulled days before his light heavyweight title fight with Daniel Cormier after testing positive for clomiphene and Letrozole, while heavyweight Brock Lesnar was revealed to have failed pre-fight and fight-night drug tests for hydroxyl-clomiphene after winning a unanimous decision over Mark Hunt. Recently, a pair of past doping violations found resolution when former UFC featherweight challenger Chad Mendes and middleweight Ricardo Abreu both received two-year bans from competition.All those accusations and years-long suspensions clustered together make it seem like MMA is a wasteland of needle stickers and pill poppers. That Jones—possibly the greatest fighter of all time and one who genuinely didn't look the part of a juicer, at least until he started doing heavy box squats—is on the list stings badly. It's the grown-up equivalent of finding out Santa Claus is really just your sleep-deprived dad. But in a more important sense, it shows that the USADA program is working, or that it's at least more than lip service. If you care about clean sport—and even if you don't mind if someone dopes to run faster or jump higher, you should care when it comes to a trauma-based pastime like MMA—then you need to watch fighters fall from their pedestals. Better to face the ugliness than live in blissful ignorance.To hear Novitzky tell it, pulling fighters from cards and causing scrambles for late replacements doesn't him bring personal satisfaction. "Let me be clear: Just because this is my program, those days and those occurrences are challenging," he told MMA Fighting. "I never want to see that happen. I don't take any pleasure that the program is working, seeing that happen. Sometimes one or two of those needs to happen for everybody to open their eyes. If anybody had any reservations about the seriousness, about the independence of the program, that it doesn't matter if you're the first on the depth chart of the roster or the last you're going to be treated the same under this program."But one downside of USADA's proliferation of testing lies with a burden that was there before. The whereabouts policy that all UFC fighters are compelled to follow looks like something you'd read after meeting with your probation officer. The difference is that fighters are independent contractors who pay their own taxes, not convicted felons. (Not usually, anyway.) And while most fighters understand the spirit of random drug testing—that it's intended to directly and indirectly level the playing field, and that embracing it gives you pseudo-drug-free credibility—those unannounced visits are intrusive and potentially distracting. They take time and energy away from the thing you're actually paid to do. How can you not resent knowing that you're going to be subject to more of them than ever before in the next few months?And when USADA knocks on your door at an inconvenient hour, how can you smile when you've just very recently seen that that this whole charade might not even matter? The lab didn't return Lesnar's allegedly dirty pre-fight sample until after the trio of 29-27 scores was rendered. "The whole reason of this program being in place is to prevent things like that from happening, prevent two individuals from getting into an Octagon where one has an unfair advantage," Novtizky said. "But based on timing, that potentially could be inevitable."That's an enormous logistical problem that the UFC and USADA need to fix—whether through expedited testing of pre-fight samples or some other measure—because as Novtizky implies, the Lesnar episode undermines the whole intent of the system. And ramping up testing doesn't mean much if a fighter with the profile of Brock Lesnar—especially with all that scrutiny that came with his relief from the four-month "retirement" obligation by which other fighters are bound—can slip through the cracks.Still, you'd be a fool to hate expanded testing. It means more opportunity to weed out banned substances, more incentive for fighters to stay clean, and more source material for Khabib Nurmagomedov's fractured, beautiful insults—even though he was only tested six times.

Advertisement

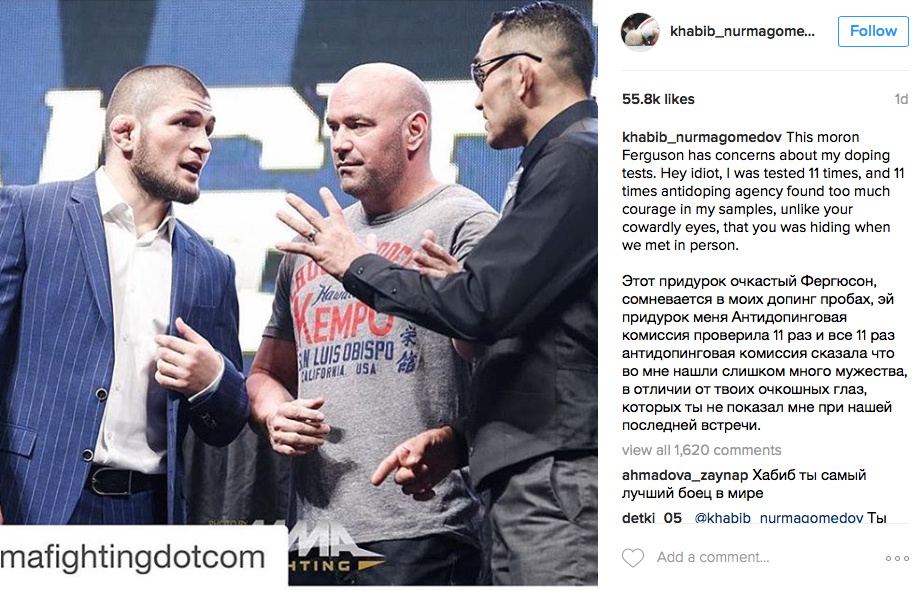

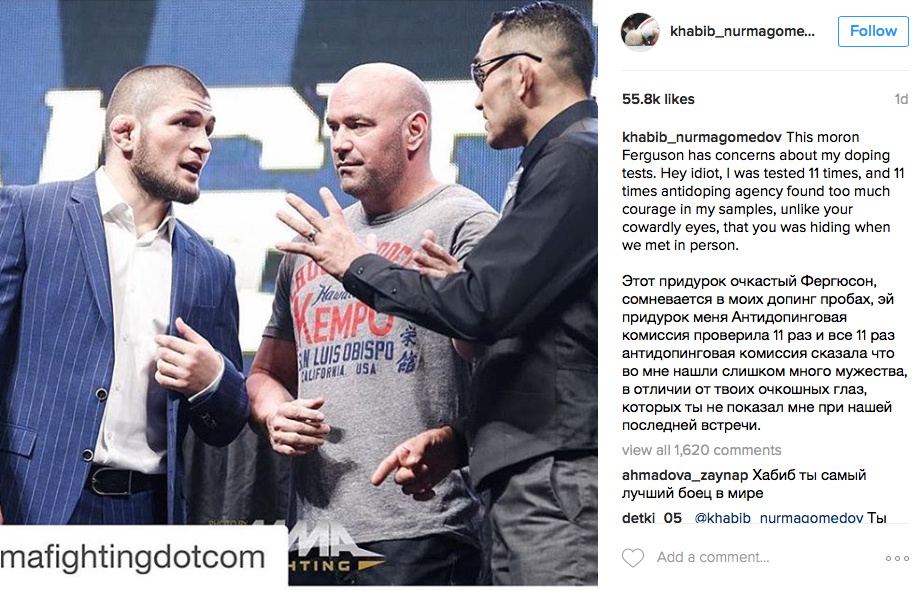

Advertisement