This is a condensed version of Gareth McConnell’s essay from ‘Looking for Looking for Love,’ a photobook documenting the 1980s nightlife in one of the UK’s seaside nightclubs in Merseyside’s. See a full gallery of photos from the book here.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK

Videos by VICE

I can only speculate about what happened to the people in these pictures. Perhaps, like those I shared the dance floor with, they joined the dole queue or became students or apprentices. Became parents and joiners and accountants, went to the docks or the shipyards, became builders and police officers (bent or otherwise), crooks, drug dealers, musicians, alcoholics and addicts, suicides, murderers, or murder victims. Became prisoners, émigrés, rich, poor or poorer—or all of the above.

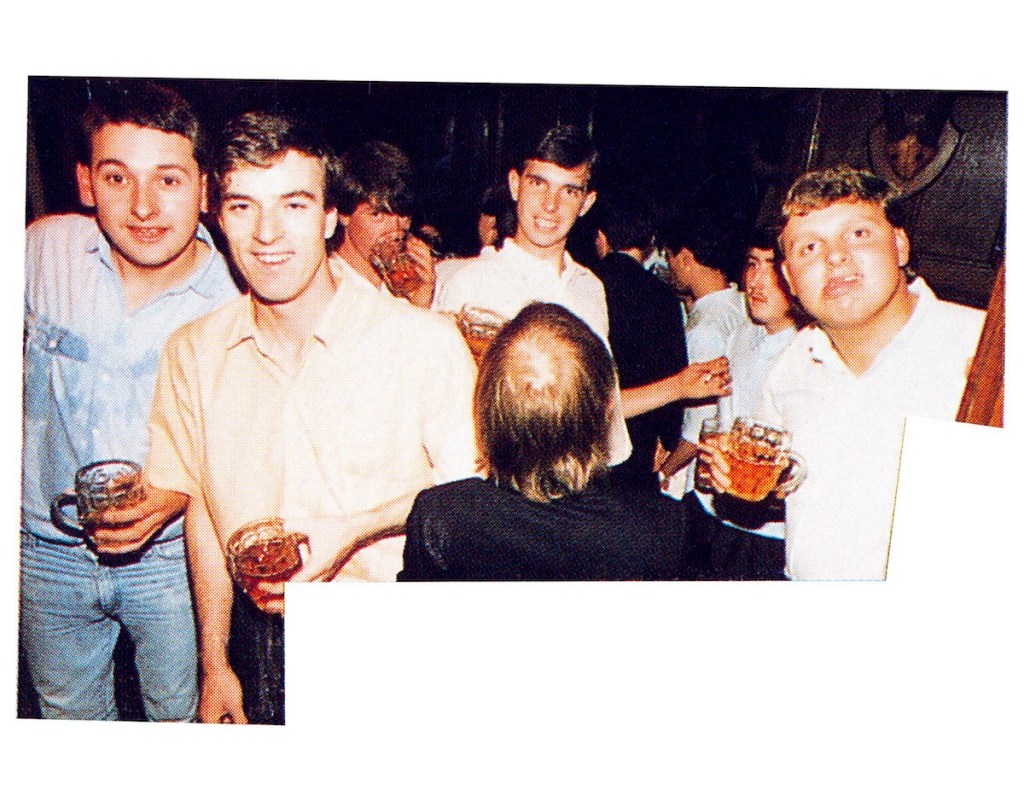

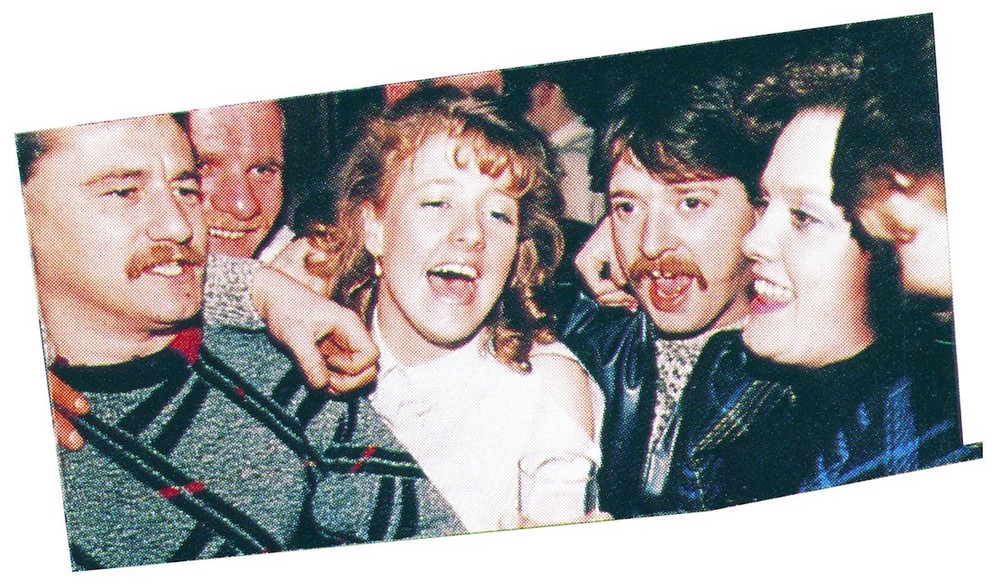

What I do know is that Tom Wood’s Looking for Love book provides a glimpse of British nightlife dancing towards the explosion of one of the most significant and mythologized youth-cultural phenomena the country has ever seen—the acid house movement and the birth of the ecstasy generation.

I never set foot in the Chelsea Reach, where Tom took his photos, but I have been to plenty of places like it: Sparkles down the road in Carrick, The Coach in Banbridge, The Crescent on Sandy Row, and the king of them all, Kelly’s in Portrush. I remember the pints of lager, the smoke, the sticky carpets and slippery dance floors, the fake IDs to get you past the aggro bouncers. I remember screaming to be heard above the music, when it was so packed you couldn’t fucking move.

I remember the smuggled quarter bottle and a five deal of hash, and talking about it all on Monday morning at school coz we were only 13 or 14 when we started going. I remember the clothes and the hairstyles and the music, and I see the faces of my childhood friends and adversaries. I see my sister in a skinny black tie, white buttoned-down shirt, and a perm. I see the girls I kissed, the unrequited loves and lost sweethearts, my own and everyone else’s.

I see Skimmer, who would start unbuttoning his trousers to the first beats of Man 2 Man Meets Man Parrish’s “Male Stripper,” and then spend the next half hour prancing about in a pair of C&A undies. I see the older girls who wouldn’t look at you twice and the nutty boys who would beat you if you were caught looking. I see the exuberance and hope and frustration and fragility and defeat of youth all mixed up in one boozy, smoky, hormonal stew—swaying spinning, groping, snogging, shouting, laughing. I see the queue at the chippies and smell the burger vans. I see the inevitable fights and tears and flashing lights, a hand-job if you’re lucky, a party, the walk home, the lift, the coach, someone’s bed or couch or floor or cell.

I remember when we all started taking little pills and powders and squares of perforated paper with tiny pictures of smiley faces and strawberries printed on them, when we started wearing baggy clothes and growing our hair and hugging strangers and freaky dancing till dawn and telling each other we loved each other. I remember smoking big spliffs on the comedown and talking shit and walking home at noon the next day or the day after that listening to the birds sing.

I remember putting all our old records and cassettes under the bed because we knew we weren’t gonna need them anymore. I remember driving round the country and putting on nights and doing deals and reading Mixmag and The Face and i-D, as well as saving up for a trip to Ibiza and thinking just maybe anything’s possible after all. There was gonna be no more slow dances for us, no more lights on, and getting your coat at 1 AM, no more drunken fights and sausage suppers. We were going raving, and so was everybody else.

It’s hard for me to look back at these pictures without a warm sense of nostalgia, but then simmering through comes a great anger and disappointment at what has been lost. Over 25 years on, with the Criminal Justice Act of 1994 ancient history but its agenda still reverberating, every mouse click and phone call can be spied on, the NHS is up for sale, Legal Aid dismantled, and the 2011 riots dismissed as ‘apolitical’—if we just set aside economic and social inequalities, the housing crisis, stop and search, police profiling.

But no need to worry, you can post comments about it on Facebook or Twitter, maybe borrow a few hundred quid off Wonga and boogie on down to the corporate festival of your choice, complete with security and sniffer-dogs. ‘Drug use will not be tolerated here! … unless, of course, it’s this pint of warm piss for five (taxable) English pounds, thank you very much.’

Lorded over by oligarchs and sneering politicians we find ourselves in the midst of more banking-induced austerity, struggling with student fees and Workfare and zero-hour contracts, and slim-to-no chance of getting a trade or an apprenticeship—and even if you do, good luck with those rights. So switch on the telly or pick up a paper and drink in your fill of lifestyle bile: food, celebrity, and property porn masquerading as culture, quietly vilifying the disenfranchised: “Lock up the poor, be a grass, be a tout, dial this number, you’re not like them. Fuck em.’ Until it’s you they’re coming for.

Looking for Looking for Love is out now on Sorika.

More

From VICE

-

A waterfall in Sungai Tekala Recreational Forest, Hulu Langat, Selangor. Photo: Zaki Mohamed / Getty Images -

Photo: Catherine Falls Commercial / Getty Images -

Photo: RYosha / Getty Images