Photos By Aaron Lake Smith The Limousin region in central France bears the distinction of being one of the most depopulated areas of the country. The cloudy mountains and plateaus are dense with evergreen forests, babbling brooks, and Roman ruins, rugged and beautiful as Idaho or Montana, with the corresponding draw for Hemingway-inspired fly fishermen and hunters. The rocky landscape is notoriously poor for farming, and there is hardly any local economy besides a bit of summer tourism—most of its residents eke out lives as livestock farmers or string themselves from year to year on modest French unemployment benefits, which amount to around 350 euros a month.This mountainous area, almost the dead center of the country, has a tradition of rural communism that dates back to the French Revolution. Even today, many of the tiny towns and villages here sport ancient communist mayors who have been reelected over and over through the decades. Limoges, Limousin’s largest city, a bland place that’s known for its porcelain industry, has been under socialist control for more than a century. When the Nazis invaded France during World War II, the mountains and woods of Limousin were so filled with communist French Resistance that the invadingWehrmachtreferred to the area as “Little Russia.” The residents of the area still proudly remind visitors that its forests were some of the few places in Vichy France that were never successfully occupied by the Germans during World War II, thanks to its maquis armies, which waged a vicious guerrilla war on the invading Nazis. Limousin, and the surrounding areas, which are historically ignored by the rest of France, have recently come to prominence due to events in a tiny, inaccessible mountain village of about 100 people called Tarnac. This town has become the fulcrum of a heated national debate about the Sarkozy government’s use of the term “terrorism” and the difference between “terror” and the deeply held French tradition of sabotage. In 2004, a group of about 20 Parisian squatters and radical grad students began surveying villages around France for a place to which they could relocate and start collectivizing. Tarnac was one name on a long list and was considered not due to any personal connections to the region but because of its rich communist history and the presence of a sympathetic communist mayor. The small group settled there, creating a node from which its people could move back and forth between the village and Paris. They bought a disused farmhouse, planted a garden, and began to raise livestock. They also took over the operation of a failing bar and general store, two of the only businesses in the town, and ran them as volunteer collectives.In 2008, a prominent French criminologist named Alain Bauer was surfing Amazon.com when he randomly stumbled on a book calledL’insurrection qui vient(The Coming Insurrection). It was put out by the French publishing house La Fabrique and written by an anonymous collective that called itself the Invisible Committee. Sensing some kind of a link between this group and European direct-action groups of the 70s and 80s like the Baader-Meinhof Gang (properly known as the the Red Army Faction), Bauer promptly bought 40 copies of the book and distributed them to domestic-surveillance professionals across France, who had been alerted by Interior Minister Michèle Alliot-Marie to be on the lookout for a rise in “ultra-leftist” and “anarcho-autonomist” cells across Europe. The term “ultra-leftism” originated in Weimar Germany in the 1920s to describe radicals who were opposed to both Bolshevism and liberal democracy. It was resurrected to describe the nihilistic strain of insurrectionary activity, without any stated demands or goal, that emerged after the antiglobalization movement of the early 2000s. Sarkozy and Alliot-Marie had been deeply unsettled by the immigrant and university unrest that had burned across France in 2005. They watched the bitter street battle between young people and the police in Greece throughout 2008. France’s own domestic-security police suspected the group in Tarnac of being the anonymous authors of the incendiaryComing Insurrectionbook and began to perform surveillance on them. The Tarnac group’s alternative way of life made them immediately suspect: They were young people with a history as squatters and anarchist activists who had left the bustling Parisian metropolis to go and live in a forsaken village in mountains that had been, historically, a site of guerrilla warfare. That many of the Tarnac group didn’t use cell phones only aroused police suspicion further, a fact the French government later menacingly ascribed to their need to avoid detection.In late October and early November of 2008, horseshoe-shaped iron rods were used to sabotage the overhead wires of several high-speed train lines in Limousin, putting a halt to rail traffic in the region and resulting in significant delays. The sabotage was done with the purpose of stopping the trains and couldn’t have resulted in any injuries or derailments. Soon after, on November 11, hundreds of masked domestic-security police descended on sleepy Tarnac and arrested nine of the young communards, who were then accused by the Interior Ministry of being part of an “association of wrongdoers in relation to a terrorist undertaking.” This was a significant and singular charge for France, a country that has a long and venerable history of sabotage but little understanding of “domestic terrorism.” In the days after the arrests, Tarnac was swarmed by journalists who sensationally reported on the bucolic village with labels such as “terror nest.” When asked aboutThe Coming Insurrection, the Tarnac communists claimed to be familiar with “that book” but denied writing it—for good reason.The Coming Insurrectionspecifically advocated interrupting the flow of state infrastructure as a step toward insurrection. After the initial tide of media reaction died down, French public opinion turned abruptly in the Tarnac Nine’s favor. The group began to be viewed as scapegoats for a Sarkozy government that had gone mad, petrified of terrorists and racist against Muslim immigrants. Suddenly, the Tarnac Nine were seen as simple youth who had moved from Paris to quaint Tarnac to pursue what they, their parents, and their neighbors tenderly described as a “different way of life.” The Tarnac Nine quickly became the darlings of the post-’68 intellectual French left.Julien Coupat, one of the more charismatic and prolific suspects of the Nine, had been the editor of a popular post-Situationist radical philosophy journal calledTiqqun(active from 1999 to 2001), the tone of which bore a striking resemblance toThe Coming Insurrectionand other Invisible Committee literature. The Tarnac Nine gained the support of famous public intellectuals Slavoj ZŠizŠek, Alain Badiou, and Alberto Toscano, who demanded that they be freed and not be called terrorists. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben wrote an article in the French newspaperLibérationon their behalf. It probably helped that many of the Tarnac Nine came from nice, wealthy families and had gone to graduate school for philosophy, thus making it possible for the media to spin them as a new, sexy Situationist movement rather than rabid proletarians living out in the country. The Tarnac Nine were ultimately imprisoned for six months and then released on judicial probation until their trial, which has yet to take place. They were required to report to police supervision each week to ensure that none of them would flee trial. As an “association of wrongdoers,” the nine close friends have been barred from congregating together since the arrest.In the dawn hours of November 27, 2009, the French antiterror police descended into Tarnac once again to arrest a new suspect for the case, a man in his 30s named Christophe, whom the police believed to be close with the Tarnac Nine. Enraged by the arrest, the Tarnac Nine went on the offensive and wrote an acerbic letter to their judges that was published inLe Mondeon December 3, titled “Why We Will No Longer Respect the Judicial Restraints Placed Upon Us.” In the letter, they explained that they were going to stop reporting to the police and that they had already disobeyed the order that prevented them from congregating. They wrote: “We think it will be good to see each other again… we have already done [so] to write this very text.” One would have expected that such a hearty slap to the cheek of authority might have triggered a clampdown on the Tarnac group. Not so. The prosecution, perhaps mindful of the relatively small amount of evidence available to convict the Tarnac Nine and a lack of public support for a prosecution, backed down in the face of the indignant letter and got rid of the judicial supervision. However, to save face, the judge and prosecution held firm that it was still illegal for the Tarnac Nine to congregate, something they had already done.Robespierre, the moral arbiter of the French Revolution, coined the word “terrorism.” It is strange that the first person to use this word was a Frenchman and a revolutionary. It is also strange that a word that, in our times, conjures images of bomb-strapped, Allah-worshipping fundamentalists, was first used by the state against its own citizens. Robespierre felt the French needed theTerrorismeto buttress the tenuous revolutionary state against the counterrevolutionaries and aristocrats—both real and imagined—that he saw everywhere. Robespierre was the ruthless vegan straight-edger of his time—he didn’t hesitate to behead his friends to uphold the virtues of revolutionary purity. After the French Revolution had killed off all its real enemies, it went through an internal cleansing, trying to purify the stained, bourgeois revolution with the liberal use of the guillotine. Perhaps it is because the French Revolution was so heavy-handed with the judgmental moralism that the French have developed such an intransigent love of sinful bourgeois pleasures like red wine, beef tartare, and satin sheets. But at the same time, the French have an innate hatred of the police and authority. They love to see outlaws break the rules and get away with it. In 2009, an armored-truck driver named Toni Musulin became a French folk hero when he drove off with a cargo equal to $17 million in cash. Fan groups sprouted up on the web, and the entire country rooted for him and seemed disappointed when he was eventually tracked down and caught.In fact, sabotage and antisocial behavior are rampant in France. In 2007, an investigation by the French newspaperLe Figarouncovered that the French rail system had been attacked 27,000 times that year by malicious vandals and sabotage. If you’ve ever flown or taken a train in France, you know that all of the major industries routinely go on strike. Militant union employees also stage wildcat strikes and conduct acts of sabotage or trash the offices of their bosses. It is in this social and political atmosphere that the Tarnac Nine are suspected, with tenuous evidence, of being terrorists.

The Limousin region in central France bears the distinction of being one of the most depopulated areas of the country. The cloudy mountains and plateaus are dense with evergreen forests, babbling brooks, and Roman ruins, rugged and beautiful as Idaho or Montana, with the corresponding draw for Hemingway-inspired fly fishermen and hunters. The rocky landscape is notoriously poor for farming, and there is hardly any local economy besides a bit of summer tourism—most of its residents eke out lives as livestock farmers or string themselves from year to year on modest French unemployment benefits, which amount to around 350 euros a month.This mountainous area, almost the dead center of the country, has a tradition of rural communism that dates back to the French Revolution. Even today, many of the tiny towns and villages here sport ancient communist mayors who have been reelected over and over through the decades. Limoges, Limousin’s largest city, a bland place that’s known for its porcelain industry, has been under socialist control for more than a century. When the Nazis invaded France during World War II, the mountains and woods of Limousin were so filled with communist French Resistance that the invadingWehrmachtreferred to the area as “Little Russia.” The residents of the area still proudly remind visitors that its forests were some of the few places in Vichy France that were never successfully occupied by the Germans during World War II, thanks to its maquis armies, which waged a vicious guerrilla war on the invading Nazis. Limousin, and the surrounding areas, which are historically ignored by the rest of France, have recently come to prominence due to events in a tiny, inaccessible mountain village of about 100 people called Tarnac. This town has become the fulcrum of a heated national debate about the Sarkozy government’s use of the term “terrorism” and the difference between “terror” and the deeply held French tradition of sabotage. In 2004, a group of about 20 Parisian squatters and radical grad students began surveying villages around France for a place to which they could relocate and start collectivizing. Tarnac was one name on a long list and was considered not due to any personal connections to the region but because of its rich communist history and the presence of a sympathetic communist mayor. The small group settled there, creating a node from which its people could move back and forth between the village and Paris. They bought a disused farmhouse, planted a garden, and began to raise livestock. They also took over the operation of a failing bar and general store, two of the only businesses in the town, and ran them as volunteer collectives.In 2008, a prominent French criminologist named Alain Bauer was surfing Amazon.com when he randomly stumbled on a book calledL’insurrection qui vient(The Coming Insurrection). It was put out by the French publishing house La Fabrique and written by an anonymous collective that called itself the Invisible Committee. Sensing some kind of a link between this group and European direct-action groups of the 70s and 80s like the Baader-Meinhof Gang (properly known as the the Red Army Faction), Bauer promptly bought 40 copies of the book and distributed them to domestic-surveillance professionals across France, who had been alerted by Interior Minister Michèle Alliot-Marie to be on the lookout for a rise in “ultra-leftist” and “anarcho-autonomist” cells across Europe. The term “ultra-leftism” originated in Weimar Germany in the 1920s to describe radicals who were opposed to both Bolshevism and liberal democracy. It was resurrected to describe the nihilistic strain of insurrectionary activity, without any stated demands or goal, that emerged after the antiglobalization movement of the early 2000s. Sarkozy and Alliot-Marie had been deeply unsettled by the immigrant and university unrest that had burned across France in 2005. They watched the bitter street battle between young people and the police in Greece throughout 2008. France’s own domestic-security police suspected the group in Tarnac of being the anonymous authors of the incendiaryComing Insurrectionbook and began to perform surveillance on them. The Tarnac group’s alternative way of life made them immediately suspect: They were young people with a history as squatters and anarchist activists who had left the bustling Parisian metropolis to go and live in a forsaken village in mountains that had been, historically, a site of guerrilla warfare. That many of the Tarnac group didn’t use cell phones only aroused police suspicion further, a fact the French government later menacingly ascribed to their need to avoid detection.In late October and early November of 2008, horseshoe-shaped iron rods were used to sabotage the overhead wires of several high-speed train lines in Limousin, putting a halt to rail traffic in the region and resulting in significant delays. The sabotage was done with the purpose of stopping the trains and couldn’t have resulted in any injuries or derailments. Soon after, on November 11, hundreds of masked domestic-security police descended on sleepy Tarnac and arrested nine of the young communards, who were then accused by the Interior Ministry of being part of an “association of wrongdoers in relation to a terrorist undertaking.” This was a significant and singular charge for France, a country that has a long and venerable history of sabotage but little understanding of “domestic terrorism.” In the days after the arrests, Tarnac was swarmed by journalists who sensationally reported on the bucolic village with labels such as “terror nest.” When asked aboutThe Coming Insurrection, the Tarnac communists claimed to be familiar with “that book” but denied writing it—for good reason.The Coming Insurrectionspecifically advocated interrupting the flow of state infrastructure as a step toward insurrection. After the initial tide of media reaction died down, French public opinion turned abruptly in the Tarnac Nine’s favor. The group began to be viewed as scapegoats for a Sarkozy government that had gone mad, petrified of terrorists and racist against Muslim immigrants. Suddenly, the Tarnac Nine were seen as simple youth who had moved from Paris to quaint Tarnac to pursue what they, their parents, and their neighbors tenderly described as a “different way of life.” The Tarnac Nine quickly became the darlings of the post-’68 intellectual French left.Julien Coupat, one of the more charismatic and prolific suspects of the Nine, had been the editor of a popular post-Situationist radical philosophy journal calledTiqqun(active from 1999 to 2001), the tone of which bore a striking resemblance toThe Coming Insurrectionand other Invisible Committee literature. The Tarnac Nine gained the support of famous public intellectuals Slavoj ZŠizŠek, Alain Badiou, and Alberto Toscano, who demanded that they be freed and not be called terrorists. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben wrote an article in the French newspaperLibérationon their behalf. It probably helped that many of the Tarnac Nine came from nice, wealthy families and had gone to graduate school for philosophy, thus making it possible for the media to spin them as a new, sexy Situationist movement rather than rabid proletarians living out in the country. The Tarnac Nine were ultimately imprisoned for six months and then released on judicial probation until their trial, which has yet to take place. They were required to report to police supervision each week to ensure that none of them would flee trial. As an “association of wrongdoers,” the nine close friends have been barred from congregating together since the arrest.In the dawn hours of November 27, 2009, the French antiterror police descended into Tarnac once again to arrest a new suspect for the case, a man in his 30s named Christophe, whom the police believed to be close with the Tarnac Nine. Enraged by the arrest, the Tarnac Nine went on the offensive and wrote an acerbic letter to their judges that was published inLe Mondeon December 3, titled “Why We Will No Longer Respect the Judicial Restraints Placed Upon Us.” In the letter, they explained that they were going to stop reporting to the police and that they had already disobeyed the order that prevented them from congregating. They wrote: “We think it will be good to see each other again… we have already done [so] to write this very text.” One would have expected that such a hearty slap to the cheek of authority might have triggered a clampdown on the Tarnac group. Not so. The prosecution, perhaps mindful of the relatively small amount of evidence available to convict the Tarnac Nine and a lack of public support for a prosecution, backed down in the face of the indignant letter and got rid of the judicial supervision. However, to save face, the judge and prosecution held firm that it was still illegal for the Tarnac Nine to congregate, something they had already done.Robespierre, the moral arbiter of the French Revolution, coined the word “terrorism.” It is strange that the first person to use this word was a Frenchman and a revolutionary. It is also strange that a word that, in our times, conjures images of bomb-strapped, Allah-worshipping fundamentalists, was first used by the state against its own citizens. Robespierre felt the French needed theTerrorismeto buttress the tenuous revolutionary state against the counterrevolutionaries and aristocrats—both real and imagined—that he saw everywhere. Robespierre was the ruthless vegan straight-edger of his time—he didn’t hesitate to behead his friends to uphold the virtues of revolutionary purity. After the French Revolution had killed off all its real enemies, it went through an internal cleansing, trying to purify the stained, bourgeois revolution with the liberal use of the guillotine. Perhaps it is because the French Revolution was so heavy-handed with the judgmental moralism that the French have developed such an intransigent love of sinful bourgeois pleasures like red wine, beef tartare, and satin sheets. But at the same time, the French have an innate hatred of the police and authority. They love to see outlaws break the rules and get away with it. In 2009, an armored-truck driver named Toni Musulin became a French folk hero when he drove off with a cargo equal to $17 million in cash. Fan groups sprouted up on the web, and the entire country rooted for him and seemed disappointed when he was eventually tracked down and caught.In fact, sabotage and antisocial behavior are rampant in France. In 2007, an investigation by the French newspaperLe Figarouncovered that the French rail system had been attacked 27,000 times that year by malicious vandals and sabotage. If you’ve ever flown or taken a train in France, you know that all of the major industries routinely go on strike. Militant union employees also stage wildcat strikes and conduct acts of sabotage or trash the offices of their bosses. It is in this social and political atmosphere that the Tarnac Nine are suspected, with tenuous evidence, of being terrorists. In a rare published interview with Julien Coupat (often labeled as the leader of the Tarnac Nine), inLe Monde, he responded to the question “Why Tarnac?” by writing, “Go there, you will understand. If you don’t, no one could explain it to you.” The forgotten, heavily wooded area around Tarnac is the French equivalent of the Zapatistas’ mysterious Lacandon Jungle. Tactically, it is an excellent location to hole up and forgo capitalism. It is not easy to get to Tarnac. From the rail station in Limousin’s capital, Limoges, I boarded a bullet-shaped shuttle train bound for Eymoutiers, a small village 30 miles down the mountain from Tarnac. The two-car train looked like a rail magnate’s private chariot, decked out from ceiling to floor in beige carpet and soft-lit lamps. The only other passengers on board with me were two Methuselah-esque old ladies who got off at snowy, abandoned-looking villages on the way up the mountain. The train ratcheted through the snow and frost, a desolate landscape of ice-crystal rivers, looming mountains, centuries-old stone houses passing in the fading light out the window. When it hissed to a stop, I was the last person on board aside from the conductor. I stepped out into the cold. Eymoutiers twinkled with pale Christmas lights. A steep, ice-covered stone staircase led up into a desolate public square. An old lady on the town’s main street pointed the direction to Tarnac and I tried to hitchhike, but it was too dark and cars blew past me, throwing up gray slush from the road. While standing in front of one of Eymoutiers’s two bars trying to figure out what to do next, I met a French guy named Matthieu. Like millions of other college students across the world, Matthieu was back home for the Christmas holiday. He said he had nothing to do and, sensing my predicament, offered to give me a lift up to Tarnac in his truck. The ride that followed can easily be ranked among the most terrifying automotive experiences of my life. Matthieu swerved us up the snow-covered mountain on a one-lane road around precipitous switchbacks where one wrong move would have sent us over a sheer cliff. The darkness was total except for a thin little sliver of sunset that lingered near the horizon.Matthieu was familiar with the unfolding drama of the Tarnac affair. “A lot of us around here feel like those people were singled out,” he told me. When I asked him whether the residents of the neighboring towns felt threatened by the presence of the insurrectionists, Matthieu shook his head. “No one cares much or feels strongly about them except for a handful of right-wing students.” After one last sharp grade up the mountain, the road leveled us out into Tarnac, past the dark, shuttered stone houses of the little village’s main street. Matthieu dropped me off at a dimly lit bar with two old gas pumps rusting in front of it. Inside, a bucolic village scene transpired—old men drinking wine and young French parents playing with their babies in the beery haze. The bar was plain, with little decoration other than a withered Christmas tree in the corner and a taxidermied warthog head hanging on the back wall. The only notable cultural ephemera that distinguished the space from an average French drinking establishment were a couple of large glossy “Support the Tarnac Nine!” posters that advertised protests in Paris and Limoges, and a wall pasted with a smattering of photocopied black-and-white fliers for radical-movie nights and collective spaghetti dinners. Most people in the bar were partnered off into hetero couples. Like some caricature of the back-to-the-land movement, the men were ruggedly handsome in a traditionally French way, with their wool sweaters and cigarettes; the women were plain and severe, worn-looking, as if they had been prematurely aged from the butter-churning and child-rearing that revolutionary discipline demanded of them. I was approached by an astringent woman in her 30s with curly hair and steely eyes who introduced herself as Gabrielle. “It’s a peculiar time for you to come visit here,” she said coldly, “I just got back yesterday.” Gabrielle explained that she had been one of the Tarnac Nine and for the past year had been shuttled between prison and judicial probation.After the judicial supervision was removed, Gabrielle and the rest of the Nine had instinctively returned to Tarnac, where they had been building the skeletal infrastructure for regional communism before they were interrupted. When I asked her how it felt to be back home and off probation, she scrunched up her face and said, “It’s very weird.” Gabrielle shuffled around the bar talking to people in furtive whispers, seeming suspicious about my visit. “The police are always watching us,” she explained, “and the paranoia is part of it.” Another guy chimed in, saying, “When the police kidnap ten of your friends and start calling them terrorists, then yes, of course people get paranoid.” Throughout the remainder of the evening, Gabrielle swung back and forth between politeness and revolutionary stridency. “What is it you wanted to see here?” she asked me. “You know, we are not some subject to be studied by an ethnologist. You can’t just come to this place and know it. You have to live it.”The Tarnac group made their thoughts on journalism clear on page 2 of their anonymously authored bookCall: “The prize of infamy [goes] to the journalists, to all those who pretend to rediscover every morning the misery and corruption they noticed the day before.” Unlike revolutionary groups of the 20th century, who used the media to cultivate their mythos and to get their message out, the Tarnac communists want nothing more than to be left alone. The media is intentionally avoided, only to be utilized for specific purposes, such as to help get their friends out of jail. In the wake of their arrests, Tarnac Nine support committees have sprung up all over France and in other countries like Greece and Germany. In New York City, an unlicensed public reading fromThe Coming Insurrection, held at the Union Square Barnes & Noble, turned into a rowdy march to the high-end cosmetics store next door, where the participants disrupted shopping and shouted, “All power to the communes!” One “Support the Tarnac Nine” demonstration in Limoges ended up at the SNCF rail-company headquarters, where demonstrators attacked the building and smashed windows. While the Tarnac Nine have supporters all over the world, many of them seem to want to quietly go about their lives in peace. One woman I met in the village said, “I can’t wait until the world forgets about this place.”Unlike many Western radicals, who wear their political beliefs on their sleeves, the Tarnac communists have melded into small-town life seamlessly and are practically indistinguishable from “normal” villagers. In much of the West, radical spaces have a unique and identifiable aesthetic; graffiti, t-shirts, patches, and flags present a dizzying array of social messages: Free Mumia! Stop Genetic Engineering! Ride Your Bicycle! Smash the Patriarchy! In contrast, you would feel comfortable bringing your grandmother to a bar in Tarnac. It is utterlyordinary, barren of clandestine sexiness or confrontational signifiers, yet it still harks back to a simpler, more revolutionary time. The room smells of tobacco smoke, there are only two kinds of beer, and there is no sign of any corporate advertising or flat-screen televisions. It looks like the kind of place where people in the 19th century would gather to discuss a coup d’état. The modern European squatter, that pierced and patched mutant of the past 25 years, is nowhere to be seen. The Tarnac communists are, in fact, resolutely post-squatter, having come to the belief that radicals putting themselves into social ghettos—organizing themselves into cliques, organizations, and social milieus—isn’t a path to building serious long-term alternatives. The most suitable historical comparison to what they are doing is the Russian Narodniks of the 19th century. In the 1870s, thousands of young radicals born into aristocratic families in Moscow forsook their class and moved out to the rural villages to practiceNarodnichestvo[People-ism, or populism], donning sheepskin garb to blend in and foment anti-czarist sentiment among the peasants. The height of this brief tendency was the “Going to the People” effort in 1874, when thousands of Narodniks left the cities en masse and moved to the villages. They learned peasant customs, ate peasant food, and dressed like peasants. The young anti-czarists were often received with suspicion, as it was all too apparent that they were not peasants. In the end, the “Going to the People” movement was brutally repressed by the czar, whose secret police descended on the villages to beat and imprison the nihilist revolutionaries and any of their peasant sympathizers.

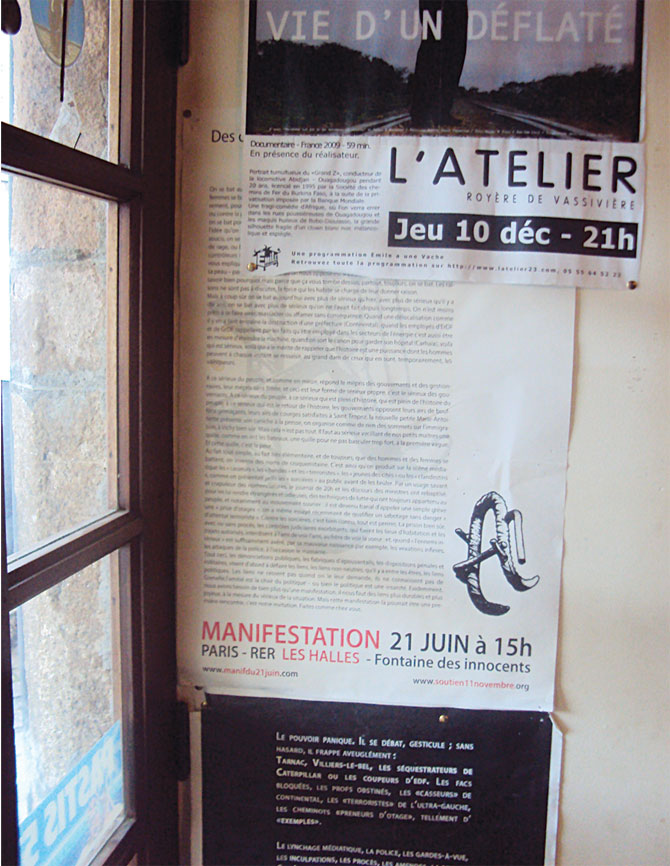

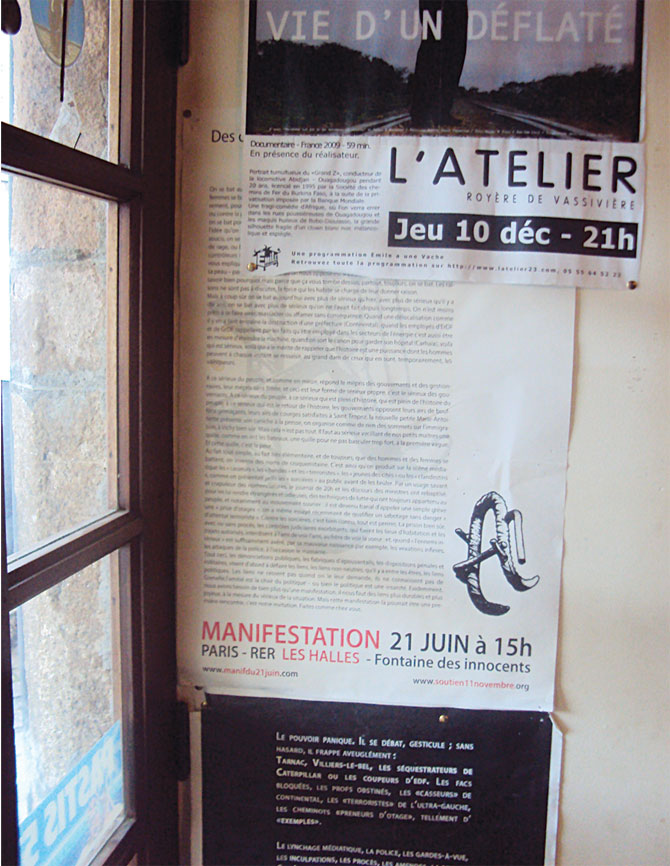

In a rare published interview with Julien Coupat (often labeled as the leader of the Tarnac Nine), inLe Monde, he responded to the question “Why Tarnac?” by writing, “Go there, you will understand. If you don’t, no one could explain it to you.” The forgotten, heavily wooded area around Tarnac is the French equivalent of the Zapatistas’ mysterious Lacandon Jungle. Tactically, it is an excellent location to hole up and forgo capitalism. It is not easy to get to Tarnac. From the rail station in Limousin’s capital, Limoges, I boarded a bullet-shaped shuttle train bound for Eymoutiers, a small village 30 miles down the mountain from Tarnac. The two-car train looked like a rail magnate’s private chariot, decked out from ceiling to floor in beige carpet and soft-lit lamps. The only other passengers on board with me were two Methuselah-esque old ladies who got off at snowy, abandoned-looking villages on the way up the mountain. The train ratcheted through the snow and frost, a desolate landscape of ice-crystal rivers, looming mountains, centuries-old stone houses passing in the fading light out the window. When it hissed to a stop, I was the last person on board aside from the conductor. I stepped out into the cold. Eymoutiers twinkled with pale Christmas lights. A steep, ice-covered stone staircase led up into a desolate public square. An old lady on the town’s main street pointed the direction to Tarnac and I tried to hitchhike, but it was too dark and cars blew past me, throwing up gray slush from the road. While standing in front of one of Eymoutiers’s two bars trying to figure out what to do next, I met a French guy named Matthieu. Like millions of other college students across the world, Matthieu was back home for the Christmas holiday. He said he had nothing to do and, sensing my predicament, offered to give me a lift up to Tarnac in his truck. The ride that followed can easily be ranked among the most terrifying automotive experiences of my life. Matthieu swerved us up the snow-covered mountain on a one-lane road around precipitous switchbacks where one wrong move would have sent us over a sheer cliff. The darkness was total except for a thin little sliver of sunset that lingered near the horizon.Matthieu was familiar with the unfolding drama of the Tarnac affair. “A lot of us around here feel like those people were singled out,” he told me. When I asked him whether the residents of the neighboring towns felt threatened by the presence of the insurrectionists, Matthieu shook his head. “No one cares much or feels strongly about them except for a handful of right-wing students.” After one last sharp grade up the mountain, the road leveled us out into Tarnac, past the dark, shuttered stone houses of the little village’s main street. Matthieu dropped me off at a dimly lit bar with two old gas pumps rusting in front of it. Inside, a bucolic village scene transpired—old men drinking wine and young French parents playing with their babies in the beery haze. The bar was plain, with little decoration other than a withered Christmas tree in the corner and a taxidermied warthog head hanging on the back wall. The only notable cultural ephemera that distinguished the space from an average French drinking establishment were a couple of large glossy “Support the Tarnac Nine!” posters that advertised protests in Paris and Limoges, and a wall pasted with a smattering of photocopied black-and-white fliers for radical-movie nights and collective spaghetti dinners. Most people in the bar were partnered off into hetero couples. Like some caricature of the back-to-the-land movement, the men were ruggedly handsome in a traditionally French way, with their wool sweaters and cigarettes; the women were plain and severe, worn-looking, as if they had been prematurely aged from the butter-churning and child-rearing that revolutionary discipline demanded of them. I was approached by an astringent woman in her 30s with curly hair and steely eyes who introduced herself as Gabrielle. “It’s a peculiar time for you to come visit here,” she said coldly, “I just got back yesterday.” Gabrielle explained that she had been one of the Tarnac Nine and for the past year had been shuttled between prison and judicial probation.After the judicial supervision was removed, Gabrielle and the rest of the Nine had instinctively returned to Tarnac, where they had been building the skeletal infrastructure for regional communism before they were interrupted. When I asked her how it felt to be back home and off probation, she scrunched up her face and said, “It’s very weird.” Gabrielle shuffled around the bar talking to people in furtive whispers, seeming suspicious about my visit. “The police are always watching us,” she explained, “and the paranoia is part of it.” Another guy chimed in, saying, “When the police kidnap ten of your friends and start calling them terrorists, then yes, of course people get paranoid.” Throughout the remainder of the evening, Gabrielle swung back and forth between politeness and revolutionary stridency. “What is it you wanted to see here?” she asked me. “You know, we are not some subject to be studied by an ethnologist. You can’t just come to this place and know it. You have to live it.”The Tarnac group made their thoughts on journalism clear on page 2 of their anonymously authored bookCall: “The prize of infamy [goes] to the journalists, to all those who pretend to rediscover every morning the misery and corruption they noticed the day before.” Unlike revolutionary groups of the 20th century, who used the media to cultivate their mythos and to get their message out, the Tarnac communists want nothing more than to be left alone. The media is intentionally avoided, only to be utilized for specific purposes, such as to help get their friends out of jail. In the wake of their arrests, Tarnac Nine support committees have sprung up all over France and in other countries like Greece and Germany. In New York City, an unlicensed public reading fromThe Coming Insurrection, held at the Union Square Barnes & Noble, turned into a rowdy march to the high-end cosmetics store next door, where the participants disrupted shopping and shouted, “All power to the communes!” One “Support the Tarnac Nine” demonstration in Limoges ended up at the SNCF rail-company headquarters, where demonstrators attacked the building and smashed windows. While the Tarnac Nine have supporters all over the world, many of them seem to want to quietly go about their lives in peace. One woman I met in the village said, “I can’t wait until the world forgets about this place.”Unlike many Western radicals, who wear their political beliefs on their sleeves, the Tarnac communists have melded into small-town life seamlessly and are practically indistinguishable from “normal” villagers. In much of the West, radical spaces have a unique and identifiable aesthetic; graffiti, t-shirts, patches, and flags present a dizzying array of social messages: Free Mumia! Stop Genetic Engineering! Ride Your Bicycle! Smash the Patriarchy! In contrast, you would feel comfortable bringing your grandmother to a bar in Tarnac. It is utterlyordinary, barren of clandestine sexiness or confrontational signifiers, yet it still harks back to a simpler, more revolutionary time. The room smells of tobacco smoke, there are only two kinds of beer, and there is no sign of any corporate advertising or flat-screen televisions. It looks like the kind of place where people in the 19th century would gather to discuss a coup d’état. The modern European squatter, that pierced and patched mutant of the past 25 years, is nowhere to be seen. The Tarnac communists are, in fact, resolutely post-squatter, having come to the belief that radicals putting themselves into social ghettos—organizing themselves into cliques, organizations, and social milieus—isn’t a path to building serious long-term alternatives. The most suitable historical comparison to what they are doing is the Russian Narodniks of the 19th century. In the 1870s, thousands of young radicals born into aristocratic families in Moscow forsook their class and moved out to the rural villages to practiceNarodnichestvo[People-ism, or populism], donning sheepskin garb to blend in and foment anti-czarist sentiment among the peasants. The height of this brief tendency was the “Going to the People” effort in 1874, when thousands of Narodniks left the cities en masse and moved to the villages. They learned peasant customs, ate peasant food, and dressed like peasants. The young anti-czarists were often received with suspicion, as it was all too apparent that they were not peasants. In the end, the “Going to the People” movement was brutally repressed by the czar, whose secret police descended on the villages to beat and imprison the nihilist revolutionaries and any of their peasant sympathizers. The Narodniks had been unable to integrate into the rural peasantry because no matter what kind of peasant clothes they wore or peasant dances they learned, they couldn’t conceal their privileged, elite backgrounds. The proletariat can smell a rich kid from a mile away. Even if a rich kid is wearing rags and talking about killing the rich, their entire being is tainted with the unmistakable signs of good upbringing and wealth. It would seem to me difficult, if not impossible, for the dirt-stained locals of Tarnac to accept the faux-peasant communists from Paris without the slightest feelings ofressentiment. I met a slight blond girl named Marielle in the bar. She looked like she should have been in the movieAmélie. She told me that she had been a squatter in Paris and had moved to Tarnac in 2004, when she was 26. “In the city, it’s very hard to do the kind of things we do here,” she told me. “We have a lot of support. Everyone is very happy that we left Paris.” As we kept talking, she became introspective. “Even when I was living fully in the city—going to parties and bars—I didn’t really like that life.” She explained that the octogenarian communist mayor of Tarnac had assisted the group when they first moved to the village by supplying construction materials and providing moral support. It was a minor disaster when he stepped down and a younger, more conservative mayor was elected, the first non-communist in generations. Marielle shook her head dourly. “The new mayor doesn’t like us. He doesn’t help us out at all. When I see him on the street, I try and avoid eye contact.”Marielle was emphatic that there wasn’t a divide between the homesteading communists and the normal villagers, and that the two groups blended seamlessly. She introduced me to a friend of hers, a kind dark-haired woman, probably in her 30s. “She is a villager. I’m from Paris. See! No difference!” Her friend nodded gingerly, “Mostly we all blend together. But sometimes the people talk…” she said, turning to Marielle, “But that’s just gossip.” Gabrielle came up and asked whether I was vegan and seemed satisfied when I told her I wasn’t. “Good,” she sneered, “veganism is something that happens in the city.” The bearded bartender wearily carved up a smoked-sausage link and passed out stubby slices to people around the bar. I felt periodic rays of antagonism emanating from a fierce-looking redhead across the room, who was wearing a fur cap emblazoned with an unironic-looking Soviet hammer and sickle. The rest of my first night in Tarnac was spent downing glass after glass of watery beer at the bar. The swarthy, blue-eyed bartender said that he, too, had been a Parisian squatter but had grown tired of the big-city life. He seemed to have drunk the small-town Kool-Aid and reiterated the familiar refrain: “We are building something here.”Hanging on the wall behind me was an old, framed black-and-white photograph, the only artifact of any age in the otherwise nondescript room. I asked the bartender who it was, and he responded weightily, “That’s Georges Guingouin. He’s a hero around here.” In the photo, which was taken in the 30s or 40s, a defiant, pugnacious-looking young man in fatigues strikes a rebel’s pose. He wears a helmet and thick black-rimmed glasses. I remembered his name from a section ofThe Coming Insurrection: “In 1940, Georges Guingouin, the ‘first French resistance fighter,’ started with nothing but the certainty of his refusal of the Nazi occupation. At the time, to the Communist Party, he was nothing but a ‘madman living in the woods,’ until there were 20,000 madmen living in the woods, and Limoges was liberated.” Guingouin was also quoted in the Tarnac Nine’s judicial-refusal letter, in which they wrote, “Georges Guingouin once said, ‘Instead of tracked prey, one must feel like a combatant.’” Guingouin is the perfect folk hero for a group of renegade French insurrectionists who want to rehabilitate the word “communism” and separate it from its long association with Karl Marx and the Soviet Union.In the early 1940s, Guingouin was the secretary of the Communist Party in Eymoutiers. He wrote an underground paper calledLimousin Worker. During the German invasion of France, the French Communist Party decided to roll over and follow Stalin’s lead after he signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact with Hitler—they urged French communists to acquiesce to the Nazi invasion. Guingouin refused the party line and acted on his conscience. He holed up in the forest and his growing maquis of French resisters waged guerrilla war on the Nazi invaders. They used scorched-earth tactics, bombing aqueducts, sniping Nazi soldiers, and destroying rail lines and bridges to cut off supplies and troops. In 1944, Guingouin and his maquis fought the GermanDas ReichPanzer division and killed their general, Heinz Lammerding. This defeat delayed theDas Reichdivision’s arrival at Normandy and was instrumental in the Allied victory over Germany in June of ’44. However, Guingouin’s war of conscience earned him a permanent place on the Communist Party’s blacklist. In 1945, he became mayor of Limoges but was subjected to such a vicious smear campaign that he was made a pariah. He left Limoges in shame and spent the rest of his life in exile as a schoolteacher. Everyone I met in Tarnac spoke of Guingouin reverently. The 2008 sabotage that resulted in the charge that the Tarnac Nine were “terrorists” was in some ways a symbolic repeat of actions Guingouin had taken in Limousin 60 years earlier. In the general store, I found a postcard with a photo of graffiti that read, “It wasn’t Julien [Coupat] who halted the trains. It was the spirit of Guingouin!” The people in Tarnac are engaged in trying to rehabilitate Guingouin’s reputation. One Tarnac communist woman told me, “Guingouin was a good man, an honest man, and a defender of his country. Because of him, Limousin was never completely occupied by the Nazis. Today, it’s really very sad. There is only one street named after him in Limoges. And it’s a very small, faraway street that nobody uses.”A place for me to stay was arranged with an affable guy in his mid-30s named Antoine, who had an unused bedroom in his house since his roommates had moved back to Paris. At first glance, Antoine looked like the kind of guy you would see on mushrooms at an outdoor Phish concert, and I felt a twinge of fear. This fear was quickly dispelled as Antoine turned out to be as insurrectionist as they come. He had grown up in the Limousin region and, after many years of squatting in Paris, had returned home in search of a more sturdy home. “We would occupy buildings and put homeless people in them,” he mused. “Then we started living in squats ourselves. They would kick us out, and we would find another building, and it would go on and on like this. We wanted something more.”The mid-2000s had been an explosive time in France—tensions over immigration and racism had erupted into widespread civil unrest after two Moroccan teenagers from the outskirts of Paris were killed while being chased by the police. President Jacques Chirac invoked a 1955 law and declared a state of emergency as cars were burned and stores were sacked all over the country. Then interior minister Sarkozy referred to the rioters asracailles[rabble, riffraff] and declared a policy of “zero tolerance” toward the civil unrest. The rage was not confined to Paris. In the French Alps, a wine festival ended with rocks and bottles being thrown and a junior high school set on fire. “Everyone was writing tracts in every little town,” Antoine said, “every university was working collectively. There were so many tracts that we would decide who we wanted to connect with based on the quality of their writing. Some were good and others were shit. I remember reading a very good one that started with a quote from Tyler Durden, fromFight Club: ‘You are not your job.’” It is worth noting here that Europeans sincerely enjoy things that Americans have long since relegated to the cultural landfill as “lame.” As we spoke, the Rage Against the Machine song “Killing in the Name” came on in the bar, and Antoine bobbed his head up and down, singing along sincerely to the lyrics with feigned fury: “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me!”

The Narodniks had been unable to integrate into the rural peasantry because no matter what kind of peasant clothes they wore or peasant dances they learned, they couldn’t conceal their privileged, elite backgrounds. The proletariat can smell a rich kid from a mile away. Even if a rich kid is wearing rags and talking about killing the rich, their entire being is tainted with the unmistakable signs of good upbringing and wealth. It would seem to me difficult, if not impossible, for the dirt-stained locals of Tarnac to accept the faux-peasant communists from Paris without the slightest feelings ofressentiment. I met a slight blond girl named Marielle in the bar. She looked like she should have been in the movieAmélie. She told me that she had been a squatter in Paris and had moved to Tarnac in 2004, when she was 26. “In the city, it’s very hard to do the kind of things we do here,” she told me. “We have a lot of support. Everyone is very happy that we left Paris.” As we kept talking, she became introspective. “Even when I was living fully in the city—going to parties and bars—I didn’t really like that life.” She explained that the octogenarian communist mayor of Tarnac had assisted the group when they first moved to the village by supplying construction materials and providing moral support. It was a minor disaster when he stepped down and a younger, more conservative mayor was elected, the first non-communist in generations. Marielle shook her head dourly. “The new mayor doesn’t like us. He doesn’t help us out at all. When I see him on the street, I try and avoid eye contact.”Marielle was emphatic that there wasn’t a divide between the homesteading communists and the normal villagers, and that the two groups blended seamlessly. She introduced me to a friend of hers, a kind dark-haired woman, probably in her 30s. “She is a villager. I’m from Paris. See! No difference!” Her friend nodded gingerly, “Mostly we all blend together. But sometimes the people talk…” she said, turning to Marielle, “But that’s just gossip.” Gabrielle came up and asked whether I was vegan and seemed satisfied when I told her I wasn’t. “Good,” she sneered, “veganism is something that happens in the city.” The bearded bartender wearily carved up a smoked-sausage link and passed out stubby slices to people around the bar. I felt periodic rays of antagonism emanating from a fierce-looking redhead across the room, who was wearing a fur cap emblazoned with an unironic-looking Soviet hammer and sickle. The rest of my first night in Tarnac was spent downing glass after glass of watery beer at the bar. The swarthy, blue-eyed bartender said that he, too, had been a Parisian squatter but had grown tired of the big-city life. He seemed to have drunk the small-town Kool-Aid and reiterated the familiar refrain: “We are building something here.”Hanging on the wall behind me was an old, framed black-and-white photograph, the only artifact of any age in the otherwise nondescript room. I asked the bartender who it was, and he responded weightily, “That’s Georges Guingouin. He’s a hero around here.” In the photo, which was taken in the 30s or 40s, a defiant, pugnacious-looking young man in fatigues strikes a rebel’s pose. He wears a helmet and thick black-rimmed glasses. I remembered his name from a section ofThe Coming Insurrection: “In 1940, Georges Guingouin, the ‘first French resistance fighter,’ started with nothing but the certainty of his refusal of the Nazi occupation. At the time, to the Communist Party, he was nothing but a ‘madman living in the woods,’ until there were 20,000 madmen living in the woods, and Limoges was liberated.” Guingouin was also quoted in the Tarnac Nine’s judicial-refusal letter, in which they wrote, “Georges Guingouin once said, ‘Instead of tracked prey, one must feel like a combatant.’” Guingouin is the perfect folk hero for a group of renegade French insurrectionists who want to rehabilitate the word “communism” and separate it from its long association with Karl Marx and the Soviet Union.In the early 1940s, Guingouin was the secretary of the Communist Party in Eymoutiers. He wrote an underground paper calledLimousin Worker. During the German invasion of France, the French Communist Party decided to roll over and follow Stalin’s lead after he signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact with Hitler—they urged French communists to acquiesce to the Nazi invasion. Guingouin refused the party line and acted on his conscience. He holed up in the forest and his growing maquis of French resisters waged guerrilla war on the Nazi invaders. They used scorched-earth tactics, bombing aqueducts, sniping Nazi soldiers, and destroying rail lines and bridges to cut off supplies and troops. In 1944, Guingouin and his maquis fought the GermanDas ReichPanzer division and killed their general, Heinz Lammerding. This defeat delayed theDas Reichdivision’s arrival at Normandy and was instrumental in the Allied victory over Germany in June of ’44. However, Guingouin’s war of conscience earned him a permanent place on the Communist Party’s blacklist. In 1945, he became mayor of Limoges but was subjected to such a vicious smear campaign that he was made a pariah. He left Limoges in shame and spent the rest of his life in exile as a schoolteacher. Everyone I met in Tarnac spoke of Guingouin reverently. The 2008 sabotage that resulted in the charge that the Tarnac Nine were “terrorists” was in some ways a symbolic repeat of actions Guingouin had taken in Limousin 60 years earlier. In the general store, I found a postcard with a photo of graffiti that read, “It wasn’t Julien [Coupat] who halted the trains. It was the spirit of Guingouin!” The people in Tarnac are engaged in trying to rehabilitate Guingouin’s reputation. One Tarnac communist woman told me, “Guingouin was a good man, an honest man, and a defender of his country. Because of him, Limousin was never completely occupied by the Nazis. Today, it’s really very sad. There is only one street named after him in Limoges. And it’s a very small, faraway street that nobody uses.”A place for me to stay was arranged with an affable guy in his mid-30s named Antoine, who had an unused bedroom in his house since his roommates had moved back to Paris. At first glance, Antoine looked like the kind of guy you would see on mushrooms at an outdoor Phish concert, and I felt a twinge of fear. This fear was quickly dispelled as Antoine turned out to be as insurrectionist as they come. He had grown up in the Limousin region and, after many years of squatting in Paris, had returned home in search of a more sturdy home. “We would occupy buildings and put homeless people in them,” he mused. “Then we started living in squats ourselves. They would kick us out, and we would find another building, and it would go on and on like this. We wanted something more.”The mid-2000s had been an explosive time in France—tensions over immigration and racism had erupted into widespread civil unrest after two Moroccan teenagers from the outskirts of Paris were killed while being chased by the police. President Jacques Chirac invoked a 1955 law and declared a state of emergency as cars were burned and stores were sacked all over the country. Then interior minister Sarkozy referred to the rioters asracailles[rabble, riffraff] and declared a policy of “zero tolerance” toward the civil unrest. The rage was not confined to Paris. In the French Alps, a wine festival ended with rocks and bottles being thrown and a junior high school set on fire. “Everyone was writing tracts in every little town,” Antoine said, “every university was working collectively. There were so many tracts that we would decide who we wanted to connect with based on the quality of their writing. Some were good and others were shit. I remember reading a very good one that started with a quote from Tyler Durden, fromFight Club: ‘You are not your job.’” It is worth noting here that Europeans sincerely enjoy things that Americans have long since relegated to the cultural landfill as “lame.” As we spoke, the Rage Against the Machine song “Killing in the Name” came on in the bar, and Antoine bobbed his head up and down, singing along sincerely to the lyrics with feigned fury: “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me!” Antoine bought several shots (on credit) of a local concoction: a bitter, Campari-like liquor called Salers mixed with raspberry syrup. The bartender scribbled down our drink orders in a tattered notebook. Antoine said good night to everybody and we left the bar. Outside, the air was cold and clear on Tarnac’s cobblestone main street. Antoine’s house was drafty and sparsely decorated, like a college dorm. Quite the opposite of the space you’d expect from the agents of radical liberation. We talked on a ratty futon downstairs, practically whispering, though no one else was home. I asked Antoine why he had moved to Tarnac. “Communism has to be lived. If you’re going to live things that haven’t been done before, there’s no one to show you the way… I don’t want to be isolated, but this is what I’m trying now.” He showed me up to my bedroom on the second floor. “The heat is not on and I have no blankets,” he said. “Good night.” It seems like you give up a lot when you take on an agrarian communist lifestyle: You exist with no job or purpose other than the ill-defined goal of “fomenting the revolution” to guide you. This sounds romantic at first as you read the literature, but it seems to pretty much boil down to milking the goats, getting into arguments with your comrades, and organizing benefits to get your friends out of jail. And as always, melancholy and inertia are pressing in on your little group, from within and without. I didn’t bring a sleeping bag to France, and so I paced around the windowless room—barren aside from a mattress on the floor in the corner. Rooting through the closet, I found some old rags, towels, and a thin sheet. I put on all my sweaters and jackets and then lay down on the mattress and covered myself with the assorted fabrics to keep warm, slowly drifting off into an anxiety-filled sleep.When I awoke the next morning and stumbled downstairs, Antoine was sitting at the kitchen table polishing off a rationed breakfast of espresso and baguette with locally produced honey and butter. We sat and chatted for a while over coffee. When I asked Antoine how he defined himself politically, he was customarily evasive: “I have a friend—when he’s around the anarchists he calls himself a communist. When he’s around the communists he refers to himself as an anarchist.” Antoine showed me a photocopied flier that his friend in London had sent him. An assortment of benign technological devices were pictured: a mobile phone, a car, a digital camera, and a computer; the text above the images read, “Terrorism: if you suspect something, report it.” Antoine laughed thinly and said, “Terrorism: If you see something… say something.” He went on to explain that he had to write all day, declining to say what or why, and suggested I go wander around town. Outside, a thin coating of snow blanketed the empty streets of Tarnac. A dog barked somewhere. Smoke poured out of the stone chimneys and gas lanterns flickered in the village’s narrow alleyways. From any street in the tiny hamlet, you could see the looming green mountains, partially obscured by low-lying clouds. I found myself drawn to the magnetic center of town, the only part vibrating with human life—but the collective bar was empty aside from a couple of leathery old Frenchmen drinking morning glasses of wine and playing cards. The door jingled as I entered the collective store next door. Similar to the bar, it bore no trace of its radical inclination—no red and black flags, no banner, no guy with a Mohawk behind the counter. Rather, a sweet, middle-aged French lady stood there. The product selection in the store is similar to what you would expect to find in a Brooklyn bodega: cans of Vienna sausages, gummy bears, macaroni and cheese, an assortment of wines; with the unique regional additions of fine cheeses, smoked meats, and hunting gear. The only thing in the shop that indicated it was run by young people who wrote sentences like “Pacificism without being able to fire a shot is nothing but the theoretical formulation of impotence” was a spindle of glossy “Support the Tarnac Nine” postcards in the corner, available for sale to tourists like me, who had come to see the collective. One had a photograph of a stencil in French that read, “Resist. Disobey. Repopulate.” Another had some stark graffiti that said, “Insubordinate Plateau.” I bought the entire set for three euros.Near the end ofThe Coming Insurrection, the Invisible Committee writes, “The exigency of the commune is to free up the most time for the most people.” What people actually “do” in Tarnac remains a mystery. While none of the individuals I met had paying jobs, and most of them lived off French welfare, no one seemed to be engaged in that most occupying of endeavors for the unemployed: loitering at the bar or store, or taking a stroll on the streets, filling up the empty hours. A palpable anxiety permeates the village, some persistent feeling that the Tarnac group is hiding something: harboring convicts, trafficking in illegal human body parts, or concealing the wreckage of an alien spaceship. Who knows? This uneasiness pervaded everything and made the narrative that the Tarnac milieu were idealistic young farmers—seeking only to live at a cozy distance from Western capitalism—a little suspect. With no action in the village, I decided to take a walk out to the group’s collective farm in a small village three kilometers away. Other than dogs barking in the distance, everything was quiet and still on the pastoral one-lane road out of town. The woods and mountains around Tarnac were mystical and strange, complete with babbling brooks and crumbling, moss-covered stone structures. The land felt alive, as if some arcadian nature god presided over it—as if it were the last hiding place for the magic of an elder time. No cars passed by as I walked in the middle of the road. Wooly horses butted their heads up against wooden fences, nudging to be petted. On the final stretch of road approaching the farm, a golden retriever ran up beside me and led the way up the hill to the old stone farmhouse. In a little corral, dozens of lambs mewed in the gloom. The golden retriever was joined by a striped cat, and the animal entourage led me over to a massive wooden barn where two individuals, a man and a woman in their mid-30s, toiled away on the building. The muscular and handsome Frenchman stepped forward, wiped sweat off his brow, and suggested that I have a look around. The property resembled any agrarian commune one might find in the United States, though the buildings were several centuries older. Broken-down cars and little trailers pocked the property. Terraced crops and compost and a little wooden outpost came together to form a beautiful vegetable garden, but for some reason, the little slice of paradise exuded a sense of exhaustion.When I got back to the house, Antoine explained that I had come at a “very strange” time. “Everything is very odd right now,” he sighed. “The way we are talking, the way we are meeting. We need new breath. If you came at other times, I believe it would be better.” Antoine’s friend Marion, a thin, friendly-looking French girl, came over and they went into another room with the laptop, seeming to have a furtive conversation over a piece of writing. When they returned, we walked to the bar. Marion explained why people were so dressed down in Tarnac. “Identity is like going to the shop. You go to the bins and pick from the merchandise. Being vegan or ‘punk’ or dressing strange is just a reason to be inactive and not actually do anything. These vegans and punks can just sit back and say, ‘Oh, I’m OK,’ and feel gratified with themselves. It’s a way to compartmentalize people into who’s worth talking to, all these surface connections. Punk, with its spikes and Mohawks, is a way to get noticed and caught by the cops. You can’t get away with anything while looking punk.”

Antoine bought several shots (on credit) of a local concoction: a bitter, Campari-like liquor called Salers mixed with raspberry syrup. The bartender scribbled down our drink orders in a tattered notebook. Antoine said good night to everybody and we left the bar. Outside, the air was cold and clear on Tarnac’s cobblestone main street. Antoine’s house was drafty and sparsely decorated, like a college dorm. Quite the opposite of the space you’d expect from the agents of radical liberation. We talked on a ratty futon downstairs, practically whispering, though no one else was home. I asked Antoine why he had moved to Tarnac. “Communism has to be lived. If you’re going to live things that haven’t been done before, there’s no one to show you the way… I don’t want to be isolated, but this is what I’m trying now.” He showed me up to my bedroom on the second floor. “The heat is not on and I have no blankets,” he said. “Good night.” It seems like you give up a lot when you take on an agrarian communist lifestyle: You exist with no job or purpose other than the ill-defined goal of “fomenting the revolution” to guide you. This sounds romantic at first as you read the literature, but it seems to pretty much boil down to milking the goats, getting into arguments with your comrades, and organizing benefits to get your friends out of jail. And as always, melancholy and inertia are pressing in on your little group, from within and without. I didn’t bring a sleeping bag to France, and so I paced around the windowless room—barren aside from a mattress on the floor in the corner. Rooting through the closet, I found some old rags, towels, and a thin sheet. I put on all my sweaters and jackets and then lay down on the mattress and covered myself with the assorted fabrics to keep warm, slowly drifting off into an anxiety-filled sleep.When I awoke the next morning and stumbled downstairs, Antoine was sitting at the kitchen table polishing off a rationed breakfast of espresso and baguette with locally produced honey and butter. We sat and chatted for a while over coffee. When I asked Antoine how he defined himself politically, he was customarily evasive: “I have a friend—when he’s around the anarchists he calls himself a communist. When he’s around the communists he refers to himself as an anarchist.” Antoine showed me a photocopied flier that his friend in London had sent him. An assortment of benign technological devices were pictured: a mobile phone, a car, a digital camera, and a computer; the text above the images read, “Terrorism: if you suspect something, report it.” Antoine laughed thinly and said, “Terrorism: If you see something… say something.” He went on to explain that he had to write all day, declining to say what or why, and suggested I go wander around town. Outside, a thin coating of snow blanketed the empty streets of Tarnac. A dog barked somewhere. Smoke poured out of the stone chimneys and gas lanterns flickered in the village’s narrow alleyways. From any street in the tiny hamlet, you could see the looming green mountains, partially obscured by low-lying clouds. I found myself drawn to the magnetic center of town, the only part vibrating with human life—but the collective bar was empty aside from a couple of leathery old Frenchmen drinking morning glasses of wine and playing cards. The door jingled as I entered the collective store next door. Similar to the bar, it bore no trace of its radical inclination—no red and black flags, no banner, no guy with a Mohawk behind the counter. Rather, a sweet, middle-aged French lady stood there. The product selection in the store is similar to what you would expect to find in a Brooklyn bodega: cans of Vienna sausages, gummy bears, macaroni and cheese, an assortment of wines; with the unique regional additions of fine cheeses, smoked meats, and hunting gear. The only thing in the shop that indicated it was run by young people who wrote sentences like “Pacificism without being able to fire a shot is nothing but the theoretical formulation of impotence” was a spindle of glossy “Support the Tarnac Nine” postcards in the corner, available for sale to tourists like me, who had come to see the collective. One had a photograph of a stencil in French that read, “Resist. Disobey. Repopulate.” Another had some stark graffiti that said, “Insubordinate Plateau.” I bought the entire set for three euros.Near the end ofThe Coming Insurrection, the Invisible Committee writes, “The exigency of the commune is to free up the most time for the most people.” What people actually “do” in Tarnac remains a mystery. While none of the individuals I met had paying jobs, and most of them lived off French welfare, no one seemed to be engaged in that most occupying of endeavors for the unemployed: loitering at the bar or store, or taking a stroll on the streets, filling up the empty hours. A palpable anxiety permeates the village, some persistent feeling that the Tarnac group is hiding something: harboring convicts, trafficking in illegal human body parts, or concealing the wreckage of an alien spaceship. Who knows? This uneasiness pervaded everything and made the narrative that the Tarnac milieu were idealistic young farmers—seeking only to live at a cozy distance from Western capitalism—a little suspect. With no action in the village, I decided to take a walk out to the group’s collective farm in a small village three kilometers away. Other than dogs barking in the distance, everything was quiet and still on the pastoral one-lane road out of town. The woods and mountains around Tarnac were mystical and strange, complete with babbling brooks and crumbling, moss-covered stone structures. The land felt alive, as if some arcadian nature god presided over it—as if it were the last hiding place for the magic of an elder time. No cars passed by as I walked in the middle of the road. Wooly horses butted their heads up against wooden fences, nudging to be petted. On the final stretch of road approaching the farm, a golden retriever ran up beside me and led the way up the hill to the old stone farmhouse. In a little corral, dozens of lambs mewed in the gloom. The golden retriever was joined by a striped cat, and the animal entourage led me over to a massive wooden barn where two individuals, a man and a woman in their mid-30s, toiled away on the building. The muscular and handsome Frenchman stepped forward, wiped sweat off his brow, and suggested that I have a look around. The property resembled any agrarian commune one might find in the United States, though the buildings were several centuries older. Broken-down cars and little trailers pocked the property. Terraced crops and compost and a little wooden outpost came together to form a beautiful vegetable garden, but for some reason, the little slice of paradise exuded a sense of exhaustion.When I got back to the house, Antoine explained that I had come at a “very strange” time. “Everything is very odd right now,” he sighed. “The way we are talking, the way we are meeting. We need new breath. If you came at other times, I believe it would be better.” Antoine’s friend Marion, a thin, friendly-looking French girl, came over and they went into another room with the laptop, seeming to have a furtive conversation over a piece of writing. When they returned, we walked to the bar. Marion explained why people were so dressed down in Tarnac. “Identity is like going to the shop. You go to the bins and pick from the merchandise. Being vegan or ‘punk’ or dressing strange is just a reason to be inactive and not actually do anything. These vegans and punks can just sit back and say, ‘Oh, I’m OK,’ and feel gratified with themselves. It’s a way to compartmentalize people into who’s worth talking to, all these surface connections. Punk, with its spikes and Mohawks, is a way to get noticed and caught by the cops. You can’t get away with anything while looking punk.” Marion explained that as far as social and political inclinations, she believed in “nothingness,” in connecting with people as she felt like it, rather than over some kind of perceived ideology, identity, or social construct. Marion was adamant about staying away from ideologies based on dead men: Marxism, Bakuninism, Leninism. She said she wanted to create a new living ideology, made among friends. “I believe politics should be a blood pact. Not something you can just revoke because you change your mind later.” After a couple of drinks, we bought groceries and several bottles of wine from the general store before it closed for the night and walked back to Antoine’s house in a big gang to make dinner. Marion and I continued our conversation while dicing up cloves of garlic for the pasta. We came onto the subject of Sartre, whom she brushed away like a mosquito. “Sartre? Sartre was the guy that all the militants would go to when they wanted to get their communiqués published in the newspapers. Nobody would arrest Sartre, and all the papers would publish his stuff but not theirs, because they were clandestine. It was a good thing, what he did, helping out the radicals. But Sartre neverdidanything. He just sat around thinking things. He didn’t put up a fight.” When I asked her what Sartre should have been doing, Marion smiled at me like I was an idiot. “Subversive action,” she said.The next morning Antoine left me a note saying he had left early in the morning to go on a skiing trip. Marion offered to pick me up from Antoine’s in the afternoon and give me a ride into Limoges. When she arrived, we jumped into her ratty hatchback. The backseat overflowed with empty bottles and soggy stacks of black-and-white propaganda newspapers. Marion smoked furiously, depositing her butts onto a mountain of cigarette butts heaped up on a retractable ashtray. She didn’t explain why she was going to Limoges. I asked her whether she worked. “Work?” she said with utter derision. “Not for money.” She said she was “dressed like a rich lady” in order to keep up the appearance that she was a normal, well-kempt adult for her weekly check-in at the unemployment-benefits office. “The administrators are worse than cops,” she spit. “They make being unemployed like having a job. Meetings, workshops, bullshit to do every week. And if they find some crappy job for me, I have to take it.” In the vertigo-inducing drive down the mountain from Tarnac, Marion explained all the things I’d been curious about but had been afraid to ask. “Look,” she said. “We are just a group of friends, not necessarily a collective. This area has no economy, no jobs or industry. Most of the houses here are abandoned, and the soil is bad. Most people move away from here to work, and then they come back. This area has a history of communism because people get educated elsewhere and return home. The only industry to speak of is tourism. After the story about Tarnac, we began to get a lot of visitors. First, the police. Then the media. Then all the gawkers who just wanted to come through, drink a coffee, and see the ‘terrorists.’ Then came the ‘cool tourists,’ who are worse than the regular tourists. They take holidays around Europe to visit the great squats and collectives and then go home to their normal jobs and their normal wives, without building anything. We are trying to mesh with the local population. Five years ago some punks moved to a village in this area. The mayor of the village was a young communist guy and he hooked them up with a house for free. They all had blue hair and talked openly about revolution and had loud punk shows all the time and pissed off the village. They didn’t build trust with the older people who are from here and eventually their house burned down. They left, building nothing. We don’t want to be like them. We want to try something new and do it on our own in the right way.”Marion continued to chain-smoke and curse as we pulled into the center of Limoges, trying to find a parking spot near the ornate, highly regarded train station. “French people like to be angry,” she said. “We would rather elect a fascist like Sarkozy and try to oust him and talk bad about him than elect a gentle socialist like Mitterrand. When Mitterrand was elected all the socialists were so happy, and they said: ‘Wow, finally we have socialism and we can just work a job or sleep or whatever.’ All the social movements died off under Mitterrand. The people were asleep. At least with Sarkozy we know who our enemy is—though for a long time, nothing happened. People were too afraid of him because he’s a madman. Now, in the past years, there have been violent demonstrations and strikes. The police have been more violent, so the people have been more violent. I prefer a bad president, because at least he keeps the people awake.”Although the communists in Tarnac repeatedly made light of the “dead plasticity” of the metropolis and the “vapid social relations” that exist in big cities, it was Tarnac that felt dead and petrified. There was little life or movement in the streets aside from the shambling of a few stray dogs. On my last day in Tarnac I woke up early and walked past the (open but empty) village bar and village store, up the road to the graveyard, perched on a bleak hill at the edge of town. There, among the girded, orderly mausoleums, the gray sky weighed down and silence reigned. A romanticized, simple life of agrarian communism seemed extraordinarily depressing.The idea of building community sounds sexy and exciting at first. But in reality, it’s a slow, encompassing process that’s more about cultivating relationships and establishing routine and familiarity. However radical and insurrectionary the belief system of rural communists, they still end up with a comfortable day-to-day existence. Antoine described the group’s move to Tarnac as “a laboratory for utopia,” as something that had never been tried before, but Maoists and frustrated hippies have been going back to the land for decades, even centuries. And just like those attempts, in Tarnac, the predictable life manages to reassert itself—communists wake up early, feed the chickens, wave hello to their neighbors, and rear their children. Neurosis, self-doubt, and jealousy, feelings as old as time, course under the town like an underground river. Not that anyone in Tarnac claims that utopia is just around the corner or that they are even getting close. For them, it’s all about the process and social experimentation, the “At least we’re trying something.” When I asked him why—what was all this leading to? Antoine just shrugged, “You can be living on a commune with your friends with everything going perfect, and then a neutron bomb explodes 50 miles away.” He raised his hands up and made a whooshing sound, imitating a bomb exploding. Then he took a sip of his coffee and smiled.