An anti-Theresa May poster released by The People's Assembly

I was wrong about Theresa May. Throughout this long agony of an election I assumed that the basic problem was that she didn't really like people very much. That this is why her rallies and photo-ops are restricted to a few thoroughly vetted supporters; why she has a habit of running away from her own speeches; why, in all her interactions with the public, she has the look of someone peeling a leech off their skin. She hates us, she doesn't want us to breathe on her, she doesn't want to catch our nasty common germs.After watching her live question-and-answer on Monday night, I'm not so sure. It might be the other way around.The post-mortem dissection of May's and Corbyn's TV non-debate mostly revolves around questions of how the candidates performed, where they lied, where they embarrassed themselves, where they had their good lines and their bad ones.But we might learn more not by watching Corbyn and May, but by paying very close attention to those short shots of the audience. How do ordinary people react when exposed, for an extended period and in a controlled setting, to the unmediated physical presence of their Prime Minister? What happens to the mind and the body when she's no longer a distant face grimacing from a TV screen, no longer an image bundled up with a few tedious catchphrases, but actually breathing in front of your eyes?From the moment May was dragged out in front of the cameras – a tense, scrawny, yowling thing, dragging her nails across the studio floor, tittering in phlegmy bursts of panic – something changed in the audience. We've seen the same tremblings in all her interactions with the public: the Aberdeenshire street that bolted its doors as she approached, the stuttering rage that overcomes anyone who actually manages to corner her. Last night, people who had sat lazily through Corbyn's question and answer session were suddenly on edge – still applauding politely at the right points, still affecting a studied interest, but breathing more quickly, shoulders hunched, jaw muscles straining, as a voice deep in the primeval brain told them to run or die.

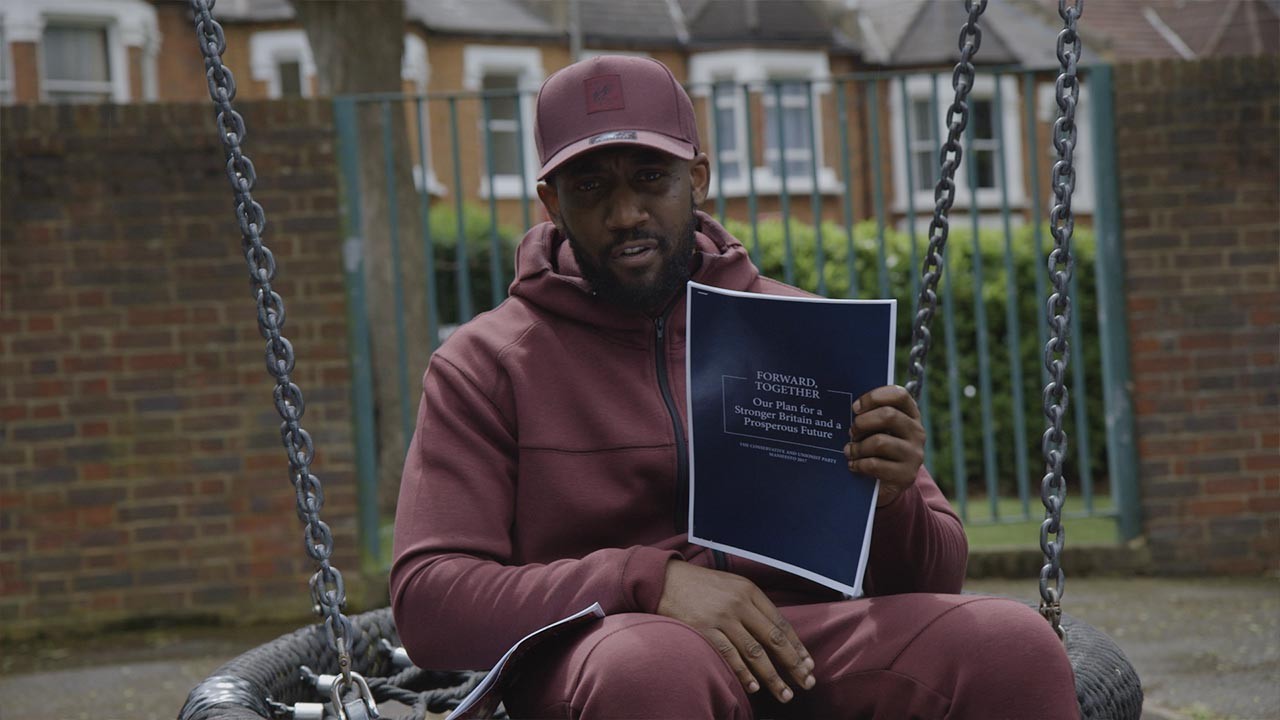

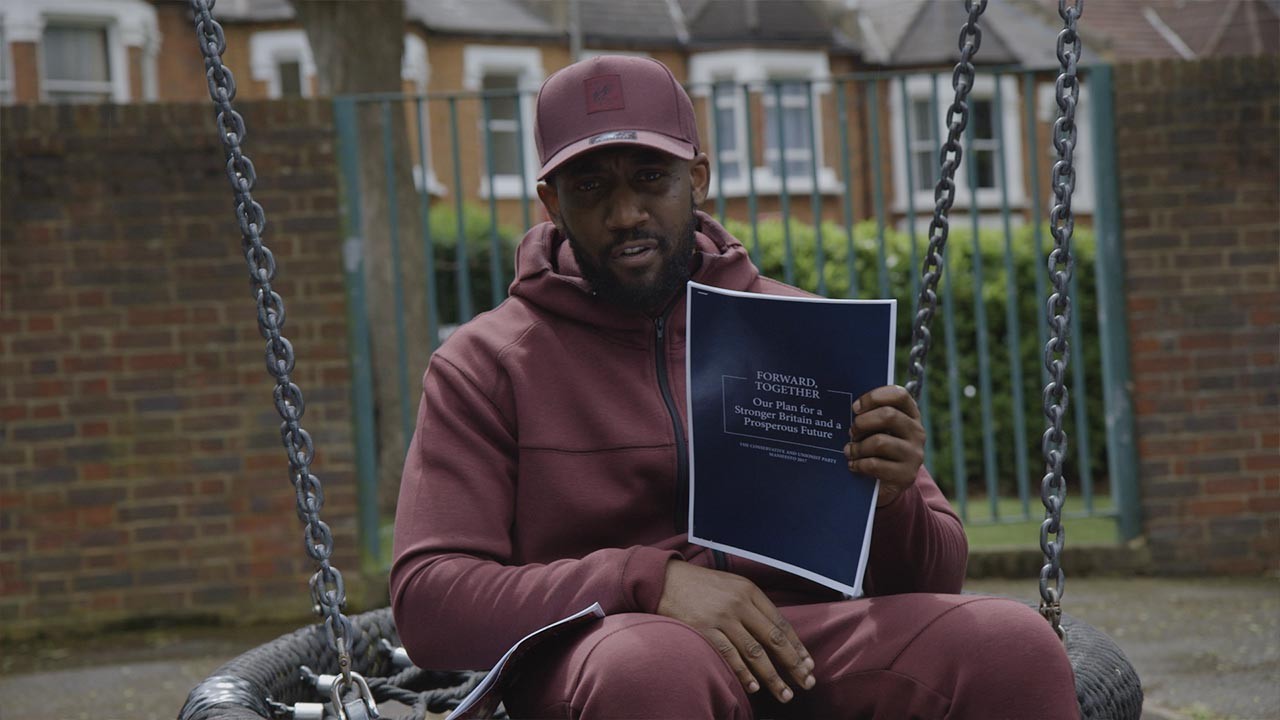

WATCH: Chat Shit, Get Elected – What's Actually in These Manifestos?

Questioners spoke to Corbyn as if they were speaking to a person. Not a person they agreed with or even liked, but a human being. They spoke conversationally, with emotive twitches and meaningful intonations and all the implicit sympathies of language. One Remain voter who wanted clarity on Labour's Brexit policy lolled her head, smiled at the stage, chatted. People said hi to him. Nobody said hi to Theresa May. It was as if they were speaking to a computer screen, or reading a part in a play: not communicating with another thinking being, but spitting words out into the void. And when that void replied, Theresa May spoke into a low, mounting, terrible silence, full of building static, the air that buzzes oppressively under a storm cloud that just won't break.But there were rumblings. When May said that nobody could ever guarantee a rise in per-pupil schools funding, laughter plopped heavily into the audience, bitter and dreadful. They interrupted – not talking to her, not really heckling, but pronouncing judgement. "Cost it!" "You've clearly failed!" The first jeers of the glorious mob. Later, when she edged her way around answering a question on the NHS, a man mouthed "bollocks, that's bollocks" as the camera swooped past his face.Animals can sense incoming evils: dogs will whimper and pace about under the clear blue skies before a storm, cats screech and scratch at burglars, sheep and cows know that the earthquake is coming, songbirds abandon the city in frantic hordes just before the high-altitude bombs come down. They live instinctively, undifferentiated from the natural world as a whole, un-alienated from the immediate future. Clearly, humans aren't so different. People tense up around Theresa May; they become agitated, they feel the presence of an unworldly danger. Macaques raised in captivity will still scream and tremble when they're shown a snake or an eagle; a buried pulse in their collective memory knows that this is a predator. And humans, without knowing why, see Theresa May in the flesh – or whatever it is that's under her skin – and an instinct, echoing down from the days when the first apes met the first lizards, tells us that this creature has come to destroy.Theresa May might well be a lizard. But there's another explanation. The Prime Minister is still dispiritingly popular – unlike Corbyn, she still has a net positive favourability rating in every poll; she was recently the most popular PM since the 70s – but it's a weird kind of popularity. The public likes her more the less they know about her, and over the course of this election they've been forced to learn a lot.Here, she's a lot like the police: people tend to like the police, in an abstract and nebulous way, but that perception immediately changes as soon as you actually meet a cop. It doesn't matter if they're giving you directions, helping you file a burglary report or hitting you in the head at a protest; opinion of the police always drops after any interaction with them.

LISTEN: The British Dream – Why Do Politicians Never Answer the Question?

It's the uneasy sense of a myth vanishing. We mostly grow up thinking that the police are tireless heroes who spend their lives fighting crime and solving murders, nourished on cop dramas and propaganda, but what actually confronts us is a tyrannical and incompetent little bureaucrat. It's a dispiriting revelation, the sudden disjuncture between image and object, or power and fantasy. A sense of abjection. A sense of disgust.Theresa May is hollow; she's nothing but myth. Most people, who are sane and don't spend their entire lives worrying about politics, knew very little about their new Prime Minister when she announced herself last year. They had to rely on a carefully calibrated image: a tough negotiator, a sensible manager, a firm hand on the wheel, joyless but pragmatic. And political journalists, who don't really know much more than anyone else, gladly contributed to it. As she rambled against liberal cosmopolitanism and hissed the eternal virtues of faith, family and flag, the media ludicrously decided that she basically shared her politics with Ed Miliband. Nonsense, but it worked; only a few dedicated weirdos like myself were paying attention.It's not working so well now; however well-crafted the myth is, she's just simply not very good at lying. Compare May to David Cameron. His most-repeated line, hammily honked through his big satellite antenna of a face, was "I believe it was the right thing to do." It's a good line. Here is someone, it says, who can exercise judgement and make the tough decisions; he seems strong, he seems stable. May, meanwhile, just loudly stomps around declaring herself to be strong and stable, without really providing anything to back it up.Theresa May's most dangerous opponent is herself. Her biological body, her intellectual emptiness, the mangy terror of a person pretending to be much greater than she actually is. This is why she won't debate, and why she's spent the entire campaign hiding behind her own name. The Tories have been fighting this election headed by a giant papier-mâché puppet of the Prime Minister, pushing her image and her myth with the furious, constant insistence that people like her. And they do, until the curtain is pulled back. As soon as the real Theresa appears, she's nothing more than someone who can't stand her ground or answer a straight question, just another internal scream trapped in a body as it slowly drift towards death.That's why she feels wrong; she pretended to be something else – the embodiment of order, the living will of the nation. But it's falling apart: she didn't seem to realise that calling an election would mean that people might start actually looking at her. The fake, mediated, digitised Theresa May is collapsing in front of us, slabs of myth falling off her frame like a collapsing ice sheet. And what's left is frailty, and terror, and disgust.@sam_kriss

Advertisement

Advertisement

WATCH: Chat Shit, Get Elected – What's Actually in These Manifestos?

Questioners spoke to Corbyn as if they were speaking to a person. Not a person they agreed with or even liked, but a human being. They spoke conversationally, with emotive twitches and meaningful intonations and all the implicit sympathies of language. One Remain voter who wanted clarity on Labour's Brexit policy lolled her head, smiled at the stage, chatted. People said hi to him. Nobody said hi to Theresa May. It was as if they were speaking to a computer screen, or reading a part in a play: not communicating with another thinking being, but spitting words out into the void. And when that void replied, Theresa May spoke into a low, mounting, terrible silence, full of building static, the air that buzzes oppressively under a storm cloud that just won't break.But there were rumblings. When May said that nobody could ever guarantee a rise in per-pupil schools funding, laughter plopped heavily into the audience, bitter and dreadful. They interrupted – not talking to her, not really heckling, but pronouncing judgement. "Cost it!" "You've clearly failed!" The first jeers of the glorious mob. Later, when she edged her way around answering a question on the NHS, a man mouthed "bollocks, that's bollocks" as the camera swooped past his face.Animals can sense incoming evils: dogs will whimper and pace about under the clear blue skies before a storm, cats screech and scratch at burglars, sheep and cows know that the earthquake is coming, songbirds abandon the city in frantic hordes just before the high-altitude bombs come down. They live instinctively, undifferentiated from the natural world as a whole, un-alienated from the immediate future. Clearly, humans aren't so different. People tense up around Theresa May; they become agitated, they feel the presence of an unworldly danger. Macaques raised in captivity will still scream and tremble when they're shown a snake or an eagle; a buried pulse in their collective memory knows that this is a predator. And humans, without knowing why, see Theresa May in the flesh – or whatever it is that's under her skin – and an instinct, echoing down from the days when the first apes met the first lizards, tells us that this creature has come to destroy.

Advertisement

LISTEN: The British Dream – Why Do Politicians Never Answer the Question?

It's the uneasy sense of a myth vanishing. We mostly grow up thinking that the police are tireless heroes who spend their lives fighting crime and solving murders, nourished on cop dramas and propaganda, but what actually confronts us is a tyrannical and incompetent little bureaucrat. It's a dispiriting revelation, the sudden disjuncture between image and object, or power and fantasy. A sense of abjection. A sense of disgust.Theresa May is hollow; she's nothing but myth. Most people, who are sane and don't spend their entire lives worrying about politics, knew very little about their new Prime Minister when she announced herself last year. They had to rely on a carefully calibrated image: a tough negotiator, a sensible manager, a firm hand on the wheel, joyless but pragmatic. And political journalists, who don't really know much more than anyone else, gladly contributed to it. As she rambled against liberal cosmopolitanism and hissed the eternal virtues of faith, family and flag, the media ludicrously decided that she basically shared her politics with Ed Miliband. Nonsense, but it worked; only a few dedicated weirdos like myself were paying attention.It's not working so well now; however well-crafted the myth is, she's just simply not very good at lying. Compare May to David Cameron. His most-repeated line, hammily honked through his big satellite antenna of a face, was "I believe it was the right thing to do." It's a good line. Here is someone, it says, who can exercise judgement and make the tough decisions; he seems strong, he seems stable. May, meanwhile, just loudly stomps around declaring herself to be strong and stable, without really providing anything to back it up.Theresa May's most dangerous opponent is herself. Her biological body, her intellectual emptiness, the mangy terror of a person pretending to be much greater than she actually is. This is why she won't debate, and why she's spent the entire campaign hiding behind her own name. The Tories have been fighting this election headed by a giant papier-mâché puppet of the Prime Minister, pushing her image and her myth with the furious, constant insistence that people like her. And they do, until the curtain is pulled back. As soon as the real Theresa appears, she's nothing more than someone who can't stand her ground or answer a straight question, just another internal scream trapped in a body as it slowly drift towards death.That's why she feels wrong; she pretended to be something else – the embodiment of order, the living will of the nation. But it's falling apart: she didn't seem to realise that calling an election would mean that people might start actually looking at her. The fake, mediated, digitised Theresa May is collapsing in front of us, slabs of myth falling off her frame like a collapsing ice sheet. And what's left is frailty, and terror, and disgust.@sam_kriss