The antiregime protests that have swept Sudan for the last week are at a crossroads, with the fervent optimism of the previous days giving way to somber reflection and shock since more 50 people are believed to have died. Sudanese activists have put the death toll far higher than that, but it may be days before the true number is known, as figures are collated from across the country after the largest antigovernment protests in decades.

Advertisement

As the working week began on Sunday, a tense calm had spread across the capital city of Khartoum. However, late in the evening the funerals of protesters and others who'd lost their lives in the unrest once again became a magnet for outpourings of anger against president Omar al-Bashir. The wide sense of outrage in the country over his two-decade rule is only being made more acute by the brutality his police and security services have displayed in their attempts to quell the revolt.Beginning in Wad-Medani on Monday and quickly spreading to other major towns, the protests were triggered by dramatic price hikes on essential goods as part of a string of austerity measures recommended by the International Monetary Fund. Subsidies on items such as fuel and cooking oil were removed overnight, almost doubling their cost.The cuts were proposed by the IMF last year, as al-Bashir's cash-strapped government struggled with losing 75 percent of the country’s oil production when South Sudan seceded two years ago. The measures were opposed by many senior members of the ruling National Congress Party, but after months of wrangling, their implementation was announced on September 22.

The security services had a good idea about what was coming. They'd warned of protests should the cuts go ahead and last week preemptively rounded up the usual suspects from Sudan’s fragile main opposition coalition, as well as other prominent activists. However, though they'd anticipated the unrest, they couldn't stop it—the protests the next morning weren't instigated by the NCP's political opponents but erupted spontaneously from the capital’s poor suburbs, where the effects of the cuts bite most.

Advertisement

“This was no revolution organized by any party of civil society groups”, said a protester who witnessed the trouble in southern Khartoum on September 25. “The government was not lying,” the eyewitness said, when they described the initial protesters as “rioters.”“I have seen people who have not had breakfast basically sabotaging everything," he said. “These people were starving." The protester I spoke to went on to describe what he saw as a “class war” with people wanting to destroy anything representing wealth, explaining the attacks on 20 gas stations and many other buildings.Sudan’s political forces and activists, who are mainly from the educated middle classes, were as surprised as the government by the numbers on the streets and quickly tried to adopt the protests as the “revolution” they had long dreamed of. They chanted slogans of “freedom, freedom” and “we have had enough” in scenes reminiscent of the uprisings across the Arab world in the last two years.Over the last week the government has moved quickly to detain political and civil society leaders in order to prevent them from mobilizing the disaffected masses. “Now nobody is on the streets,” an activist said on Sunday evening, before reports surfaced of demos at a funeral in the Burri area of Khartoum. It quickly became clear that the government had resorted to extreme measures in an attempt to put down a potential uprising.

Advertisement

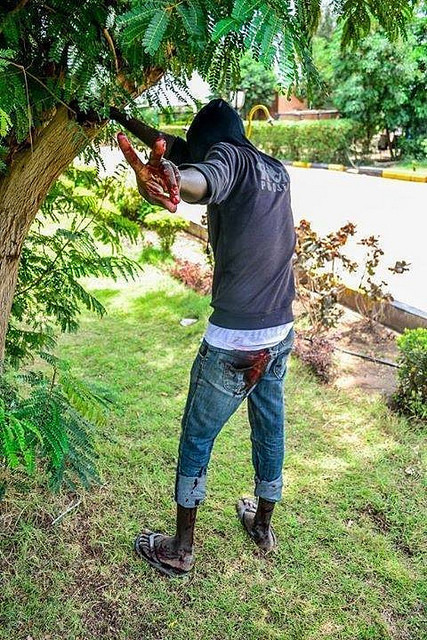

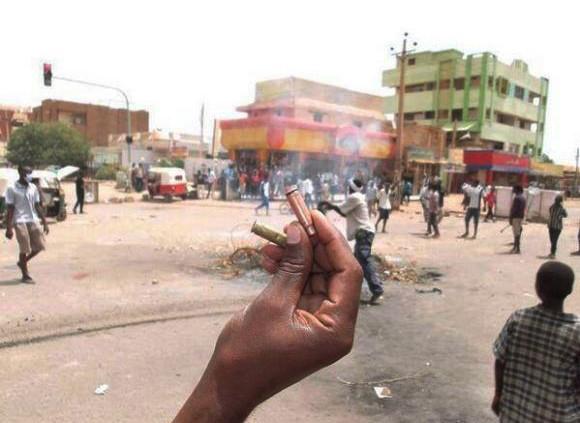

"I went out on the streets expecting the usual—a few guys firing tear gas and some rubber bullets,” the activist told me. “But they fired live rounds! I have seen people die in front of me. People have been psychologically defeated.”

He recalled seeing plain-clothed men riding on white pickup trucks with machine guns attacking protesters “with absolute impunity,” a claim made repeatedly by other eyewitnesses. The men were “shooting to kill, they were not going for the legs but the head or chest,” he said. Those activists who have not been rounded up are now keeping a low profile to avoid joining over 600 who have already been arrested, he added.The government, which has put the death toll at 29, maintains that it has not used live ammunition and has tried to blame the deaths of protesters on armed elements of rebel groups currently fighting the army in Sudan’s peripheral regions, who had somehow infiltrated the capital. A memo signed by over 25 NCP officials implicitly contradicts this denial, however. As well as calling for the subsidies to be reinstated, the memo accused the government of violently crushing protests and not allowing people to "peacefully express their views in line with the constitution."Not since Bashir’s Islamists came to power in a bloodless coup in 1989 have so many thousands walked through the streets to call for him to step down. But the NCP has no designs on stepping aside without a fight, unlike in the 1960s and 1980s, when popular uprisings forced out previous autocratic regimes. The stream of graphic videos and images uploaded to social media sites—before and after the world’s first countrywide Internet blackout since the height of the Egyptian revolution in 2011—fast became the main source of news about the protests.

Advertisement

As in other protest movements across the Middle East and North Africa, the battle for the control of information has been keenly fought. Since Wednesday, three newspapers, including the pro-government mouthpiece Al-Intibaha, have been suspended, while some other newspapers have closed in protest against the strict censorship that tends to peak during moments of national crisis. Two pan-Arab satellite channels have also been closed. Sudan TV, meanwhile, has been largely showing music programs and soccer matches.Bashir is used to tumult. He has held onto power through decades of civil war with what is now the Republic of South Sudan, a decade of conflict in Darfur for which he has been indicted for crimes including genocide, new wars in the southern border regions, international sanctions and, in 2000, an acrimonious split with some of the key Islamists that brought him to power.So, despite opposition forces, youth groups and trade unions announcing on Saturday that they'd be clubbing together to try to bring down the regime peacefully, for now at least Bashir and his National Congress Party are going nowhere—even if the violence and unrest in Sudan's streets continues to rumble on.Follow Tom on Twitter: @TomLawMediaImages courtesy of GirifnaMore from Sudan:Sudan Revolts: Internet Blackouts and Dead Protesters on the StreetsSudan's Forgotten WarriorsIt Was an Unhappy Second Birthday for the Youngest Country in the World

Advertisement