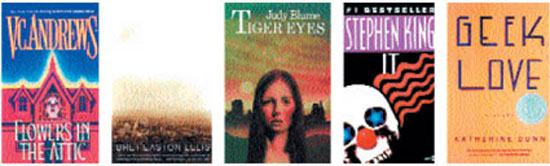

So Corrine, a beautiful blonde Aryan woman, falls in love with Chris, her beautiful blonde Aryan “half-uncle.” They marry. Over the years, they do the nasty a lot, in the process spitting out Christopher, Cathy, Cory, and Carrie, four beautiful blonde Aryan children. Chris bites it in a car accident. Corrine is fucked. Her parents are rich but they hate her and think her offspring are devil spawn. Her dad’s on his deathbed and he’s clipped her from the will. But she carts herself and the kiddies off to their creepy estate anyway to try to convince them that she’s not gross for sleeping with her uncle. This is what I learned from reading Flowers in the Attic roughly 192 times when I was approximately twelve: Families are fucked. Kids are fucked too. Grandmothers can be super-fucked. Especially when they pour hot tar in their grandchildren’s hair, brainwash the kids’ mother and lash her with a giant leather whip, put arsenic on their breakfast donuts, and lock them in big dirty attics indefinitely, starving them so they have to hunt mice and suck each other’s blood until they develop acute urges to screw one another. It’s horribly written. It’s trashy. It’s perfect. If you’re a guy, read it now. Your ability to spew forth catty pontification on the finer points of this novel will score you big points with chicks ages 24 to 29. If you’re a girl, read it again. You’ll shit. BETH WAWERNA

Advertisement

Bret Easton Ellis, 1985

This might be faulty logic, but you could say that only good books get made into movies, because, like, why would anyone spend millions of dollars on something that was crap? Of course, there’s no accounting for the damage Hollywood fuck-ups do after they option the rights to a good novel. Like how they cast Jami Gertz to play Blair in Less Than Zero, even though a huge part of her character stems from being a major blonde WASP. Or how they put Robert Downey Jr. in these horribly distracting Mary Jane sandals that just made him unwatchable as Julian. Or how in the Rules of Attraction, the screenwriters just couldn’t resist giving Paul the typical fag movie- treatment and making him really queeny and desperate, as opposed to cool and used to getting his way, like in the novel. So if you’ve been wary of reading any of this dude’s work because the film versions are horrible, see the first sentence. LYNN TRANTiger Eyes

Judy Blume, 1982

It may damn well be possible that Judy Blume and the developers of Prozac were working hand-in-hand to lower the attention span of young adults around the world. There are some chapters in this book that are no more than three paragraphs—not even half a bloody page. You tell me: Blume or MTV, which is worse? Tiger Eyes is your basic coming-of-age novel, focusing on the life of fifteen-year- old Davey Wexler. Her entire family is attempting to cope with the recent shooting death of her father during a hold-up. After Davey passes out in school a few times, her relatives insist that the whole clan (Davey’s mother and five-year-old brother Jason) stay with them for a wee bit out in New Mexico. Her relatives turn out to be overprotective, and Mom becomes severely depressed. As a method of escape, Davey takes to hiking in a nearby canyon, where she meets a stone-cold fox who calls himself “Wolf.” Turns out, he’s the son of a terminally ill cancer patient of Davey’s, (she candy stripes at the local hospital on the weekends with her boozehound-in-training friend Jane). There are some social issues discussed here, but not in a preachy, “love thy neighbor” sort of way. For any child growing up in the early 1980s, it was a perfect message encapsulated in a non-threatening medium. Yet for any contemporary teen, I doubt it will get through to their MTV-addled minds. SELENA LEONG It

Stephen King, 1987

During the winter that I first read Stephen King’s pulpy epic It, Tiffany’s “I Think We’re Alone Now” played constantly on the radio. The earnest remake totally fit the story’s theme of spunky little misfits trying to escape their families, peers and an unnameable child-eater that took on the forms of their worst nightmares. The story has more monsters then King’s entire canon combined, including bloated zombie kids, werewolves, a giant spider, a rampaging Paul Bunyan-esque statue, drainpipes that puke blood, and even a plain old abusive husband. The book’s best part is the end, when the kids realize that the only way they can save themselves is by having a little prepubescent gang bang in the sewers. Hot! JOSHUA LYON Geek Love

Katherine Dunn, 1983

This book is excellent for the next time you’re alone in you’re apartment on a Saturday night at two a.m., listening to drunken party people pass below your open window singing slurred medleys like “Last niiiiiiite she saiiiid…bitch…dolla, dolla bill, yaauhhhaaaauhhhhahhhauhhhhll,” and you feel so alone and like a gross misshapen loser for not being out. It’s about a traveling family of carny freak-show attractions, and the coolest thing about this deformed troop—which includes flipper-limbed Arturo the Aquaboy and a pair of Siamese twins—is that moms purposely made them this way by ingesting arsenic and amphetamines while pregnant. On top of that, she raised them as if their grotesqueness made them superior. It really puts perspective on the whole notion of being an outcast and what’s normal and all that, until you finally feel glad that you didn’t go out and have no friends because if you did you’d be boring. LYNN TRANThe Postmodern ConditionJean-François Lyotard, 1984

Remember being in college and how it wasn’t really cool to use the word “postmodern” anymore, but you were pretty sure that at some point it must have been the fucking buzzword of the moment? Well that moment was 1984, when the English translation of this little 110-page book by a pretentious-as-hell French philosopher named Jean-François Lyotard dropped. Impenetrable as fuck, Lyotard’s angle is that no matter how hard we try to figure shit out, all knowledge is totally precarious and ultimately has to rely on unquestioned, improvable assumptions or stories or myths that he calls “Grand Narratives.” The Postmodern Condition called into question pretty much everything that we use to try and understand the world around us: history, science, art, religion, whatever, and in the process really pissed off William Bennett. Worth reading, but even more worth having on your bookshelf to intimidate your friends. FREDERICK DE FREDERICK MONEY: A Suicide Note

Martin Amis, 1984

As Amis puts it (playing a writer named Martin Amis in his own fucking book): “You can either feel good at night or in the morning.” If you’ve ever woken up appalled by the hazy recollection of what you did the night before and tried to make yourself feel better by thinking of the people you know who have done much worse things, and if you’ve ever reached the painful realization that no one you have ever met would have behaved as badly as you fear you did last night, John Self is your man. A working- class boy who made some money directing controversial fast-food commercials, John is the willing personification of 80s excess: he jets between London and New York making arrangements for his first feature film; he throws cash around with gleeful abandon; he fucks women who are far better-looking than he is; and most importantly, he goes on spectacular, epic benders. Of course, like any true “yob,” John is almost as tragic as he is repellent.Money has scored him a hot girlfriend and lessened his chances of following the other men in his family into the British penal system, but in a rare moment of candor, he admits that he “longs to burst out of the world of money and into…the world of thought and fascination.” The revelation of a cultured, noble man hiding inside the violent, wasted slob may sound a bit too obvious, but Amis is smart enough not to let John off the hook with full-scale redemption and a neat ending. John’s decadent world was destined to collapse, and it does when the film producer turns out to be a penniless fraud. Eventually we leave John living in a hovel with a fat nurse for a girlfriend, and even if you don’t get anything else from this novel, at least you know that not only has someone done worse things than you, he’s fallen further, too. TARA GALLAGHER