Berkeley Breathed: Your question presumes a reality so distant from the experience that any questions about process are meaningless—but perfectly reasonable. The problem is that you’re asking a guy who didn’t think of any individual strip or story line longer than it takes to read this sentence. I drew in a manic, sweat-flinging state of deadline panic EVERY week. Not most weeks. EVERY week. For ten years. I drew what occurred to me as I stared at the same blank strips I’d been watching for six days, and only because the plane that would deliver them to my syndicate editor was due to take off at 5:30 AM, about seven hours from that moment. Ouch.

This is not how a comic strip should be drawn. This is not how ANY deadline should be handled by any reasonable, conscientious, grown-up professional. But as I wasn’t, they weren’t. The flip side of that confessional coin is that Bloom County would not have been what it was—whatever it was—if I’d been that thing I just described. It was art and writing born of chaos. It was the poison the madness needed. The new book—with all the chaos intact and not edited out, as it was in books before—shows that rather intriguingly. Can you talk a little about how you developed the looks for the main characters? What were some of the inspirations in terms of the art of the Bloom County universe—not just for the characters but also for the settings?

As many have read and few have doubted, Doonesbury was the stylistic key that all of us turned to in those days—college cartoonists, I mean. Jules Feiffer played a similar role for Garry Trudeau. I doubt Garry would have left the word balloons behind if it hadn’t been for Jules. I virtually didn’t have any other artistic influences, as I wasn’t familiar with other comic strips. I’m still not today. They simply were never in my sights. Why not?

Comic strips didn’t tell stories well, as slow and chopped as they are. And stories—narrative, plot, character—are what still make me sweaty with creative passion. You want to know why Bloom County was set in a rural, small-town environment? To Kill a Mockingbird. Maycomb, Alabama, was where I naturally dropped all of my imagination when it needed a setting. A therapist might help explain why, but there it is. I will say that Opus is really Scout from Mockingbird in many ways. He’s a motherless innocent, adrift and wandering about in an adult world of confusion, betrayal, and incivility. We experience it through both their eyes. But don’t think for a second that this occurred to me when I sketched a penguin for a throwaway gag in 1982. I show it in the new collection: Opus was meant to be dispensed with after his initial appearance. Go figger. And when was the last time you met a penguin in real life?

I walked with them in Antarctica in the early 80s. Swam with them in the Galapagos in 1989. I sensed—and I might be projecting here—that they knew who I was. Were you more of a Milo or a Binkley when you were a kid? I definitely felt very Binkley most of the time.

Absolutely split the difference. I think most cartoonists with an ensemble set of characters split their personality up in contrasting elements and then apply it to their characters. Not always, but to a large extent you can’t help it. So I was filled with self-doubt as Binkley was. But the little scheming media manipulator of Milo? Well, guilty. As a ten-year-old kid reading your comics, a lot of the political humor went right over my head. I remember having to ask a grown-up who Jeane Kirkpatrick was because she kept popping up in Bloom County. It’s interesting that a comic could encompass a range of characters and references that has Jesse Helms on one side and the Giant Purple Snorklewacker on the other.

I drew what seemed amusing to me. That was the extent of my thoughtfulness when it came to designing the Bloom County world. As with most cartoonists, a comic strip is an unsavory peek into the head of its maker. Having said that, I have no inkling as to the inside of Jim Davis’s head from a reading of Garfield. It was the classic corporate invention—drawn by a staff—which made it fun to skewer. It was there to sell shit. Speaking of that, did you ever hear about any reaction from Jim Davis regarding your statement that Bill the Cat started as a parody of Garfield?

Trust me, Davis could care less about being mocked. It wasn’t respect that he worked hard for. I think that a lot of kids in the 80s sort of started with Garfield when they were really young and then graduated to Bloom County. Do you have many memories of encounters with fans of Bloom County?

In the heyday, I would do signings at comic-book stores, which I’d never seen before—nor the fans of such. It was a bit of a shocker. This is pre-Comic Con. I was stunned because I could never have been in one of those crowds myself. It wasn’t in my DNA. So I had to adapt to a fan base of people that I had yet to understand. I simply didn’t come from their world. The influence I was having on the younger kids was rather sobering. Anyone who produces stories and popular art remembers when they suddenly realized that there were actual faces to the readers of one’s work and that they, in many cases, took it far more seriously than I did. I remember hearing about Harrison Ford out and out dismissing his movies’ fans as being nut jobs. He’s in the wrong business. You can sense it in his performances now. He’d rather be drunk and somewhere else. A pity. We who are lucky enough to provoke the imaginations of the public owe it to ourselves and to them to embrace the whole enchilada. It took me some years to appreciate this. Have you ever had a crazy fan?

Yes indeedy, I’ve had crazy fans. Rabid. Committable. Bloom County seemed to attract mental cases like flies to horseshit. One poor adult woman kept sending me hours of videotapes of herself talking to me, but calling me by a different name. Her family finally contacted me and apologized after she stripped in one of them. It’s both sad and deeply scary that in these days, folks can find your address in two clicks. It wasn’t like this before. We live behind gates now. Someone on our magazine’s staff sent you a fan letter when you were hurt back in the 80s, wishing you a speedy recovery. She also included a drawing she’d made of Cyndi Lauper, who was her other hero besides you at the time. Before too long, she received a really nicely personalized letter back from you. She showed it to me, and it was really sweet. Can you tell me about the accident that led to you breaking your back?

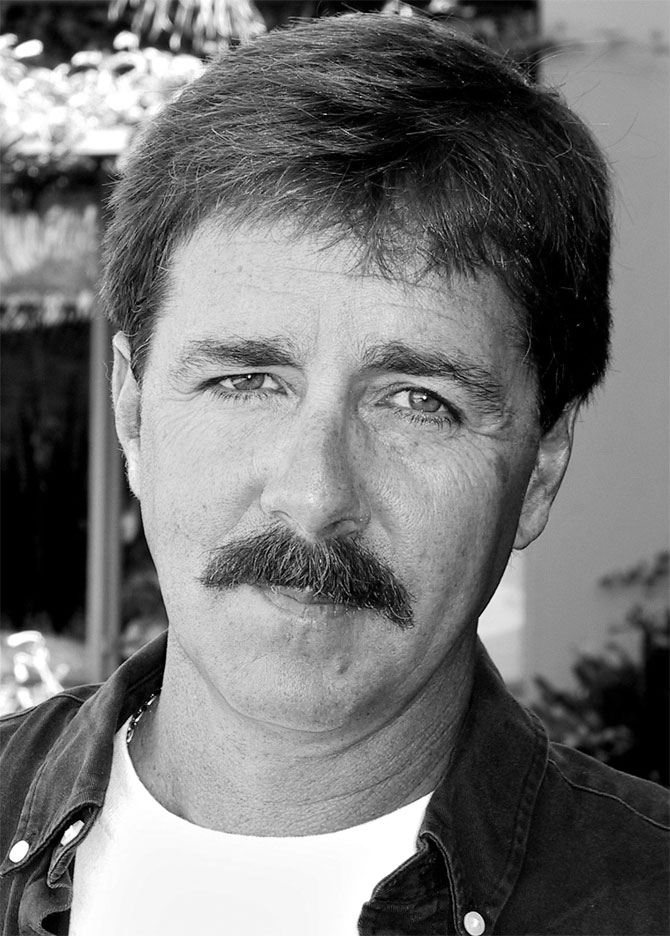

I had a problematic landing in an ultralight aircraft due to a little fuel shortage. What’s funny is that I finally ran out of gas again, 25 years later, just three days ago on Highway 101 near Santa Barbara. At night. With my whole family. Nobody broke a back this time. On the other hand, my mother was in the car. I might have preferred a broken back.Response from Berkeley Breathed to a fan letter from

Vice Managing Editor Amy Kellner in 1986.Your Wikipedia page also says that you once nearly lost an arm to a plane propeller.

Suffice it to say, let me just suggest to your readers that they not turn to the navy kid driving a speedboat and suggest that they do their job in a slightly different fashion than they are doing. What was it like going through every single Bloom County strip for the five-volume set? Did you feel nostalgic?

My editor did this, to tell you the truth. But it is indeed bracing to read these. I hadn’t in 25 years, remember. I can’t emphasize enough: My impression is that someone else did all that work. I have no memory of it, like women forget the pain of childbirth and giving oral sex. How many pets do you have?

A house full of pit bulls. Burglars and stalkers, please take note. Like all childless couples, they were our children right up until the moment that we bore real ones, and then they went back to being dogs. Very sad. Based on the photo of you on the back of the Bloom County Babylon collection and the Basselope character that you created, I would have guessed you were a basset-hound man.

Well, I’ve only had one close relationship with a basset hound and of course, like most of them, she didn’t know she was a basset hound. She believed—from all objective evidence—that she was a bunny rabbit. That’s exactly why I like basset hounds. But pit bulls eat the fans camped on my front lawn who think they want to take me with them when they go to paradise, so I keep them. Where and when do you write?

Honestly, my ideas come upon waking and are then refined in a long hot shower. I write in my studio, which looks like Captain Nemo’s organ room in the Nautilus. I edit at the back table in the sun at the Cava restaurant in Montecito, California, where they keep filling my iced tea, hoping I’ll leave after three hours. How do you handle stress?

I tell myself that I’ll never get suckered into directing a film project again. I relax after that. Everything, including watching your child tightrope across high-power lines, is less stressful than that, so there’s no excuse not to relax. What do you think you would be if you weren’t the guy who made up all this cool stuff?

A gigolo. Nice.

Listen, you asked. I can only presume that my ability to draw penguins would translate into sexual attraction. I’m wondering if you can give me an analogy that sums up the differences between Bloom County and the strip that it transitioned into, Outland. Like if Bloom County is a cheeseburger, then what is Outland? Deconstructed beef stew?

Forget the analogy. Outland was hubris. I discovered the same thing about cartoon fans that musicians discover about their fans: They don’t necessarily follow you into experimental new creative areas like panting poodles. Nor should they. So was there a consensus reaction from your fans on Outland? It was kind of like going from Help! to Sgt. Pepper’s with no acclimation period in between. I thought that was great, but I imagine some people being freaked out.

“Confused” is a more accurate way to describe the reaction. It was an instructive experience. But I do deeply appreciate your comparing Outland to Sgt. Pepper’s. You may go to magazine hell for that. I’m willing to risk that. I just finished reading your novel Flawed Dogs. A lot of it is pretty brutal and sad.

People did find it brutal. But they admitted that they found the story riveting. And that’s goal one. I thought I kept the lid on the intensity, frankly. The notion that young readers will get traumatized by your characters’ traumas is simply absurd on the face of it. Sadness and tragedy are as vital to a good story as slobber is to a pit bull. That might be my best simile ever. It’s a good one. So, one last thing. What’s the meaning of life?

I’ll tell you what the meaning of life is to a dog: us. Our own meaning is related to that. Thanks for asking. Amy Kellner helped with this interview.