Chinese social network WeChat is blowing up, and the Chinese government is watching. Image: Flick/Ming Xia

Advertisement

WeChat uses location data to hook you up with users IRL.

Advertisement

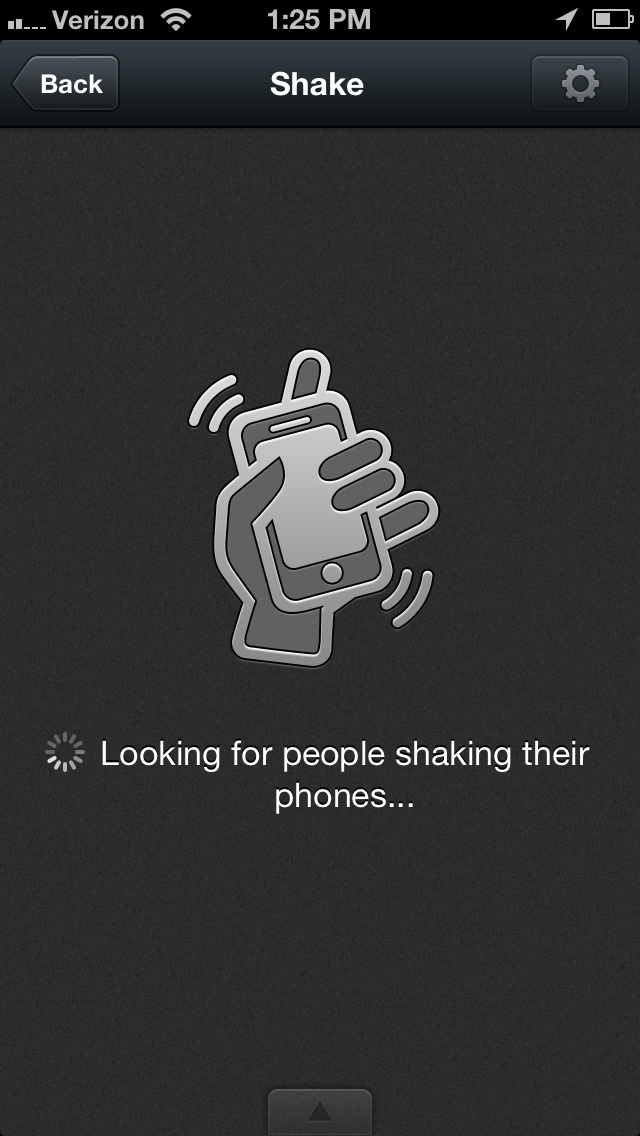

Screen grab of "Shake" a WeChat feature that helps users find

one another and exchange info.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The threat of government surveillance isn't a uniquely Chinese menace. Transparency reports recently released by Google show the US federal government has made information requests—mostly subpoenas and search warrants —for thousands of user accounts each year since at least 2009. The requests are partly for US investigations, Google explains, but also for "requests made on behalf of other governments pursuant to mutual legal assistance treaties and other diplomatic mechanisms." The number of annual requests has gone up each year since 2009, and Google's compliance rate with furnishing the information hovers consistently around 90 percent.Still, I haven’t altered my Google or Facebook behavior. And I am far from alone.“The Chinese government could in theory gain access to anything stored on a server in China.”— Jeremy Goldkorn, founder and director of Danwei

Advertisement

Advertisement

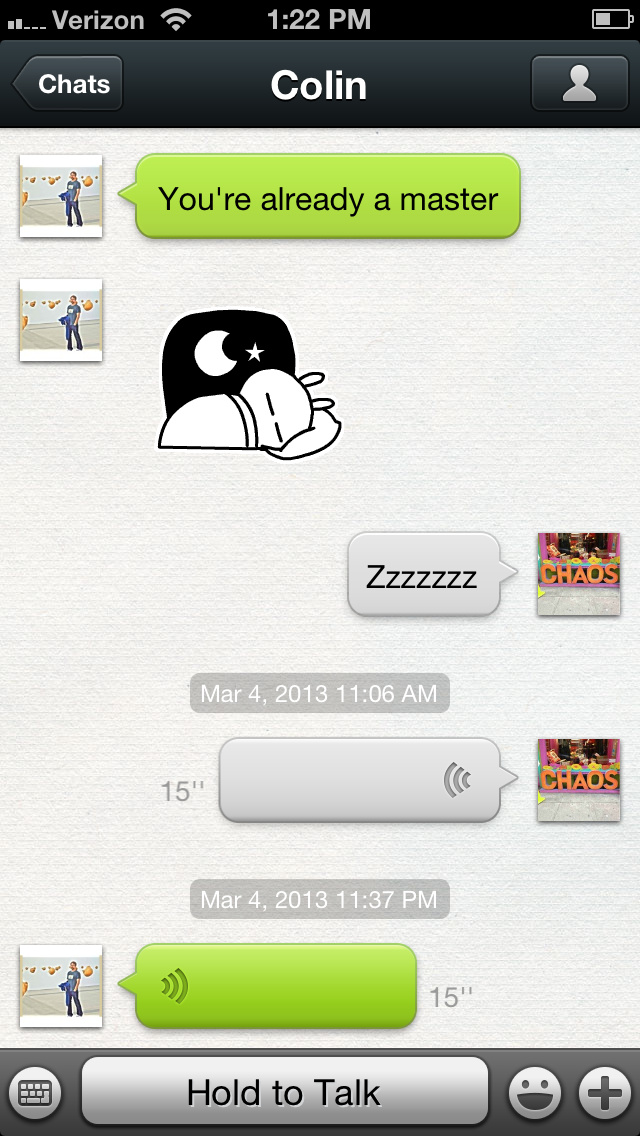

What WeChatting looks like: At the bottom, a voice message,

with an indicator of length. Higher up, a sleeping bunny.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The Big Three operators, with their not-always-aboveboard government connections, can squash any would-be tech star that dares to fly too close to the sun. Natkin said this would involve making things even more of a bureaucratic nightmare for competitors than they already are. For example, they could persuade China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology to classify certain of WeChat’s services under categories requiring a different type of license, thereby preventing it from offering those services.“In the past what they did with VoIP was say they needed to do these ‘trials’ with each of the telecoms operators, and the trials just went on and on with no end,” Natkin said.The Chinese government already does a lot of roundabout handicapping of foreign companies that make the mistake of getting too big inside its borders. Take Google: People trying to load Gmail and other Google services from within China often find their internet speed slowed to a crawl, or stare at a screen that loads indefinitely. The connection is actively being throttled by the Great Firewall, China’s internet censoring apparatus, and Google’s is just one example of many. Given this environment, it may not matter whether Tencent censors international messages or hands over sensitive user information to the Chinese government. WeChat could be shot down by friendly fire.In the end, my philosophy about putting myself in a position to be surveilled by the Chinese government is a little like my attitude towards sharing personal data with Facebook and shredding my financial statements before tossing them in the trash: I aspire to be disciplined, but past indiscretions have left me so deep in the hole that I‘ve already semi-given up.I’m wary of WeChat, or any Chinese app, spelunking through my phone and internet accounts. I’m wary of any app that mines my data, from any company or place. But as one friend felt moved to voice-message me via WeChat at 7 a.m. recently, “Dude, WeChat fills me with so much joy.”I sent back a thumbs-up emoji in agreement. I didn’t care who was watching.In China’s business environment, WeChat could be brought down by virtue of its own success.